Editor’s note: This article is part of a series for The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center’s 2022 Health Equity and Anti-Racism annual report. Read all stories in this series on the Anti-Racism Initiatives page.

Ohio is among the 10 worst states for infant mortality, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data from 2020, the most recent year available.

Of the state’s infant deaths, Black infants are more than 2.8 times likely to die than white infants, according to the Ohio Department of Health.

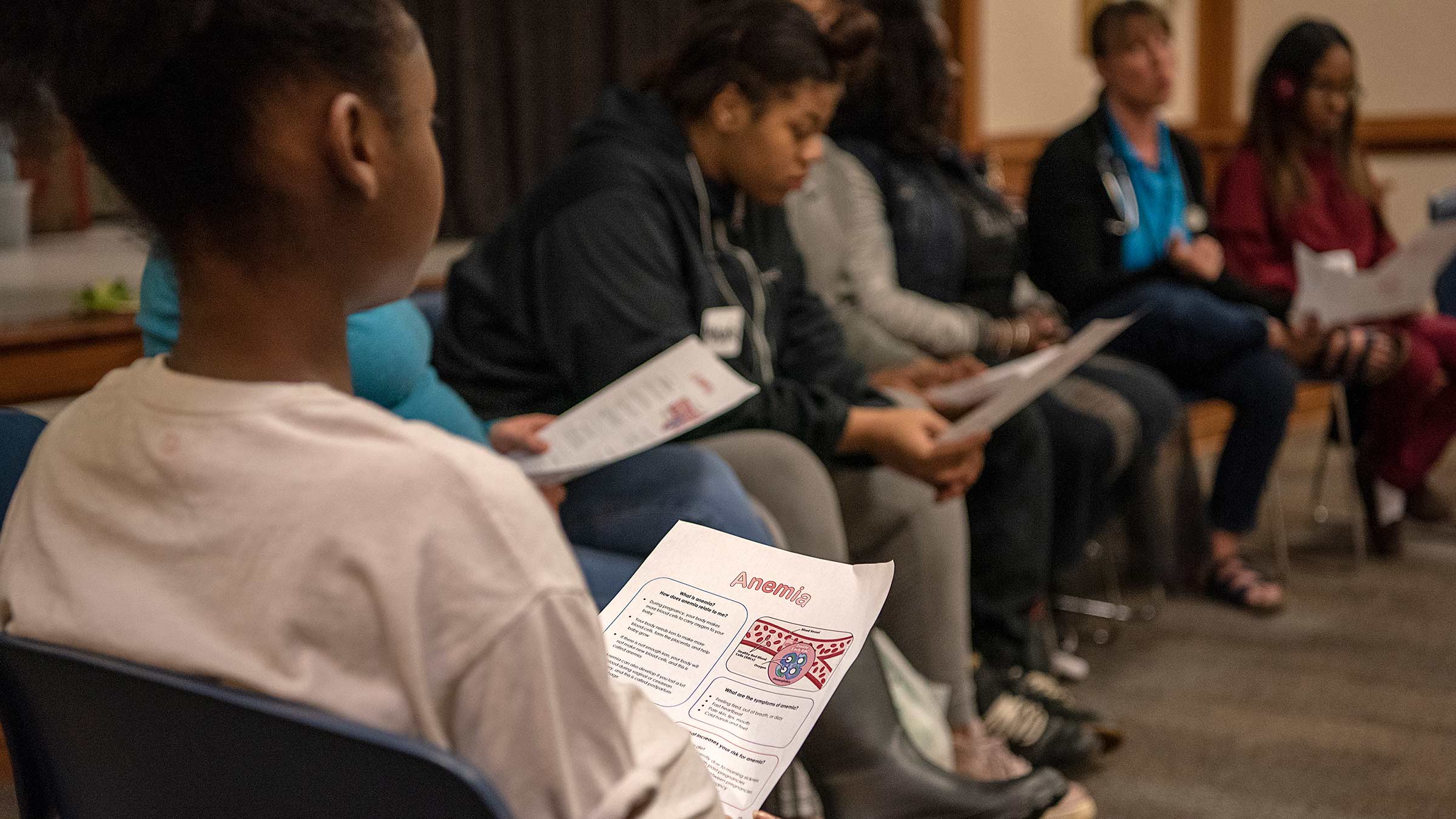

But a program to educate moms, founded in 2010 at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center by Patricia Gabbe, MD, and Twinkle Schottke, is helping improve those statistics in Franklin County. A total of 665 moms were educated about healthy habits in 2021 when the Moms2B program used a hybrid format due to the pandemic.

When Moms2B first started more than a decade ago, the infant mortality rate in Franklin County was 8.2 deaths per 1,000 live births. In 2021, it was 7.6 deaths per 1,000 live births, says Kamilah Dixon, MD, MA, the medical director of Moms2B in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center.

“We have seen an improvement in that rate since Moms2B started. Initially we were in one location and expanded to eight areas in Franklin County with the highest needs,” she says.

A total of 6.5 babies died per 1,000 live births in Ohio, according to 2020 CDC data.

Leading causes of infant mortality before a baby’s first birthday include birth defects, preterm birth and low birth weight, infant suffocation, sudden infant death syndrome and maternal pregnancy complications.

“In our program, we provide education on safe sleep, breast feeding, emotional wellness, self-advocacy, birth spacing and topics on prenatal care and what to expect in labor,” Dr. Dixon says.

The majority — 62% — of the program’s participants are Black.

“We know that many of the inequities we see are rooted in structural racism. We have a session dedicated to discussing racism in health care and provide strategies for our moms to help them navigate the health system. We also discuss the importance of self-advocacy to make sure they are heard during their care. We encourage our moms to seek care from providers they trust,” Dr. Dixon says.

In a peer-reviewed study of the Moms2B program published in the January 2021 issue of Maternal and Child Health Journal, there were positive outcomes for 675 predominantly Black (72%) and low-income pregnant women. When compared to a matched group of high-risk women who didn’t attend Moms2B, program participants had 14% fewer pre-term births, 21% fewer low birthweight infants and 55% fewer infant deaths for moms attending an average of six Moms2B sessions.

Of those mothers who didn’t receive Moms2B services, 12.7% gave birth preterm compared to 10.9% of those who had received Moms2B services.

“This represents a remarkable 1.8% decrease in pre-term births from 2011 to 2017, clearly demonstrating the mission of Moms2B to help empower healthy moms and healthy babies from birth through the first year of life and reduce the infant mortality rate,” Dr. Dixon says.

The program has helped prevent more deaths, but the COVID-19 pandemic likely worsened the death rate and presented challenges in reaching moms.

There were 6.7 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2020 for Franklin County, Dr. Dixon says.

Before the pandemic, there were two-hour in-person Moms2B sessions at eight locations with a multidisciplinary team including physicians, nurses, social workers, dietitians, patient navigators and early childhood educators. Sessions would include a heart-healthy meal, transportation and child care.

During the pandemic, the program was forced to transition to a virtual format starting in June 2020. The program began holding in-person sessions again in July 2021 and has since re-opened three sites, with plans for more to re-open in summer 2022.

The program expanded to Dayton and began holding sessions with moms virtually in fall 2020. Plans are underway to open an in-person site in Dayton in summer 2022 in collaboration with colleagues at Wright State University.

Moms2B began using the Integrated Healthcare Information System (IHIS) in 2021 to allow better communication with health care teams. IHIS is a single, integrated and personalized health record across the continuum of a patient’s interaction with the medical center.

Moms2B collaborates with Ohio State’s Community Care Coach, a mobile health unit, for which Dr. Dixon is the women’s health service leader. It allows moms to receive prenatal check-ins and postpartum care in their neighborhoods. There’s also a partnership with the Dads2B program, which teaches family units how to best advocate for their needs to ensure healthy pregnancies.

Increasing flu vaccinations in minority communities

Lower influenza vaccination rates among minorities is a challenge for health care providers to overcome.

To close a 12.9% gap between white and non-white patients receiving flu shots, the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center began a project in 2020 to ramp up efforts to increase vaccination rates.

“We set an ambitious target of 45.1%, which is 7% greater than where we ended last year at 38.1%,” says Aaron Clark, DO, medical director for the Ohio State Health ACO, an accountable care organization that provides Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries with access to high-quality care.

As of March 2022, the flu vaccination rate for minorities in central Ohio was at 38.8%, about two-thirds of the way to our measurement period, he says. Flu season runs from October through March.

The program used focus groups consisting of health system employees to learn more about hesitancy within minority groups when it comes to getting flu vaccines.

“There was a little bit of inherent mistrust of the medical system in terms of giving a vaccine. ‘You’re injecting something into my body. I don’t know what that thing is,’” Dr. Clark says. “There’s some systemic reasons why this population might not trust the larger health system. That [mistrust] persists, unfortunately, but very understandably.”

Understanding that, the program was intentional about its efforts to raise vaccination rates.

“To influence this, we deployed a multi-pronged strategy focused on engaging internal stakeholders across all care settings, redesigning internal workflows, bringing flu vaccination opportunities into the communities and developing and disseminating culturally sensitive communications,” Dr. Clark says.

There were several community-based events to offer flu shots that in some cases even allowed patients to stay in their cars as they were vaccinated.

The case for closing the disparity gap is a worthy goal: It can prevent hospital stays.

“If you have influenza, there’s a higher rate of hospitalizations and a higher rate of complications for a host of other reasons. So anything we can do to prevent illness from happening in the first place is helpful,” Dr. Clark says.

It can prevent workers from being forced to take unpaid days off from work.

“There’s also a large socio-economic impact that happens in terms of wage earners having sick leave available. If you get the flu, you are probably out for a good five to seven days from work. If you’re the primary income earner and you don’t have sick leave, or you’re just paid on an hourly rate, that’s a big impact on a monthly budget,” Dr. Clark says. “Getting a flu shot can offset that. That’s part of the equation as well.”

Overall rates for influenza vaccine administration are down for all demographics compared to historical averages in the last year after a mild flu season. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there were already efforts underway to mask and social distance. People likely felt less at risk for getting the flu and some chose not to receive a vaccine. There was also an increase in telehealth visits, which posed another barrier to administer vaccines.

In 2021, 42.1% of the medical center’s non-white patients received the influenza vaccine (35,922 patients). In 2022, 37.5% of non-white patients received the influenza vaccine (34,900 patients). There was a steeper drop with the white patient population during the pandemic. In 2021, 55% of white patients (141,502) received a flu shot but in 2022 there was just a 49.7% vaccination rate (125,775) for white patients.

“This disparity didn’t just happen. The disparity in influenza immunizations has existed for a very long time. To close that gap is hard and it takes a long time. You have to develop community trust. You have to be there when you say you’re going to be there, and you have to do what you say you’re going to do,” Dr. Clark says. “With any initiatives, we can have an impact on the community if we continue to serve as a trusted source for care. But that trust has to be earned every single time.”

Preventing unintentional overdose deaths

The opioid epidemic continues to evolve, and thousands of lives continue to be lost.

More than 5,000 Ohioans died of unintentional drug overdoses in 2020, the most current year available from the Ohio Department of Health. When compared to 2019, it’s a 25% increase.

Black males are disproportionately affected by the epidemic. They had the highest drug overdose death rate in Ohio compared with other sex and race/ethnicity groups.

The unintentional drug overdose death rate for Black people was 42.9 deaths per 100,000 population, which was higher compared to white people at 37.8 deaths per 100,000 population, according to ODH.

“We want to emphasize that it’s not only opioids anymore. Fentanyl, which is an opioid, is still the largest, leading cause of overdose deaths, but it’s more commonly being found in stimulants and fake pills,” says Alison Miller, program manager for Ohio State’s Addiction Services. “That’s something we want to make people aware of.”

Fentanyl was involved in a majority of overdose deaths in 2020 because it was often combined with other drugs including heroin, cocaine and methamphetamine.

The Ohio State Wexner Medical Center continues to offer free naloxone and training on how to administer it to overdose patients in hopes of saving lives. Since 2015, the medical center has been distributing kits to those most at risk through our Emergency Departments. Kits were distributed to the public without a prescription beginning in 2018.

The Ohio State Wexner Medical Center continues to offer free naloxone and training on how to administer it to overdose patients in hopes of saving lives. Since 2015, the medical center has been distributing kits to those most at risk through our Emergency Departments. Kits were distributed to the public without a prescription beginning in 2018.

Community events have taken center stage in the effort to reach more people impacted by drug use. Not only are naloxone kits distributed but so are fentanyl testing strips to prevent overdoses. The events take place about three to four times per month around central Ohio. Naloxone kits are also available to patients at all seven hospital locations.

From May 2021 to April 2022, The Ohio State University Project DAWN (Deaths Avoided With Naloxone) program distributed 603 naloxone kits to the community. From August 2021 to April 2022, the program distributed more than 1,200 fentanyl test strips during outreach events.

Stopping the stigma with words

There’s a group working to make sure health care providers are mindful of the language they use with patients to reduce the stigma of addiction called Stop Addiction Stigma.

The Ohio State College of Nursing offers training for staff and faculty, resident training and training videos to teach the importance of using non-stigmatizing language when talking about patients with addiction.

“Research has found that when stigmatizing language is used, information can be missed, because people assume certain things about the patient. Providers are also less likely to offer treatment and more likely to think the patient deserves punishment and blame for their addictive disorder,” says Julie Teater, MD, medical director of Addiction Medicine. “High degrees of stigma can interfere with patients seeking treatment, and patients may then have delayed care, for example, if they fear stigma. Obviously with addiction being such a deadly disease that delay in treatment can be fatal.”

Making it safe to get treatment

The Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment published a paper in February 2022 about the challenges Black patients face as they seek addiction treatment.

Based on a patient survey collected at Ohio State’s Talbot Hall, patients commonly report experiencing racial discrimination by health care workers, which may be associated with mistrust in the medical system.

The study showed that 79% of participants reported prior racial discrimination in health care. It’s unknown how prior experiences of discrimination affect Black patients’ addiction treatment.

Plans are underway to expand the residential treatment program at Talbot Hall. The program offers short-term stays of three to five days, but an expansion would allow patients to stay up to 30 days. The expansion has a tentative launch date of winter 2023.

There continues to be efforts to coordinate addiction services throughout the Ohio State health system to better care for patients. Doctors continue to prescribe fewer opioids after surgical procedures, and peer supporters are being hired as Ohio State employees.

“That is a change in terms of equity. We’re trying to decrease the stigma of staff members who are in recovery. We want to advocate that they can work in our health system and provide valuable service to our patients,” Miller says.

We’re removing barriers to better health and wellness

See how Ohio State is elevating experiences and outcomes for every patient, employee, learner and community member.

Read More