Women in medicine

How today's female physicians are forging a path for equity and representation for the next generation of women in medicine

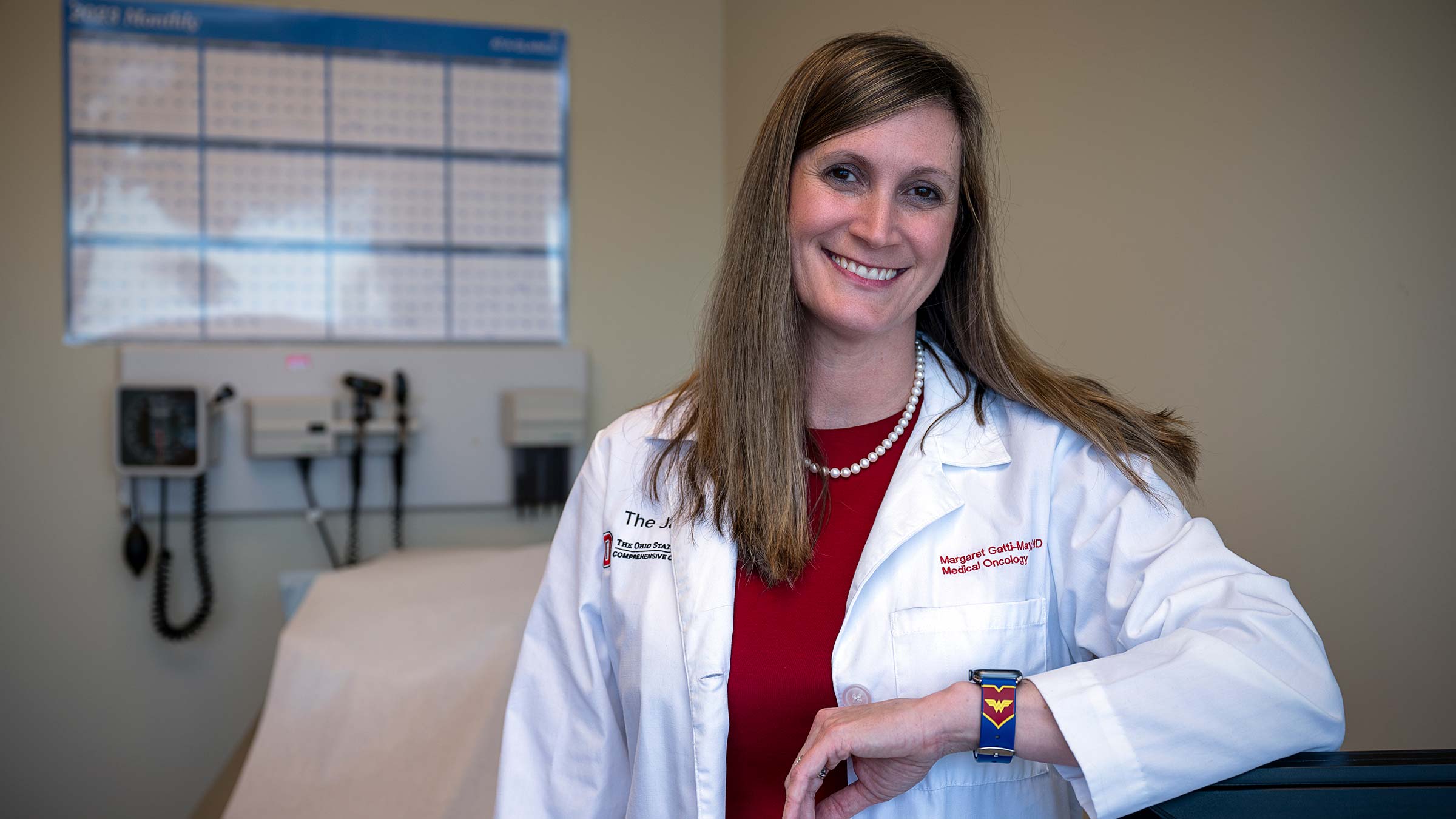

As the only female doctor in a room full of male doctors, Margaret Gatti-Mays, MD, MPH, recalls several times when she was addressed by first name only. Once among colleagues, a male pharmaceutical representative called every male physician “Doctor” and then called Dr. Gatti-Mays simply “Margaret.”

What happened next stands out. Her male supervisor stopped the meeting and asked for her to be addressed as Dr. Gatti-Mays. To this day, his response to title stripping gives Dr. Gatti-Mays the courage to speak up for herself and for others.

“That single action made me feel more empowered to the fact that I can say something. I’ve worked hard for these credentials,” Dr. Gatti-Mays says.

Equity begins by training more women in medicine

Recently, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy released a statement that includes medicine in its mission to promote equitable access to careers in STEMM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math and Medicine).

At The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, equitable representation of women in medicine doesn’t happen by accident. The first woman graduated from The Ohio State University College of Medicine in 1915, a year after the institution opened. This year’s class of first-year medical students at the college is 53% female — the ninth year that women have outnumbered men. Overall, 37% of leaders at the college are female, and 55% of students identify as a woman. Compared to peer institutions in the Association of American Medical Colleges, Ohio State ranks above the benchmark for female-to-male faculty ratios in all categories.

Members of the Women in Medicine and Science (WIMS) chapter at Ohio State support people who identify as women as they navigate equity issues and access professional development programming.

“We want to ensure women are successful, that they’re being promoted and that they stay here,” says Kristy Townsend, PhD, associate professor of Neurological Surgery in the Ohio State College of Medicine and director of WIMS.

Taking on medical specialties once dominated by men

Cindy Baker, MD, clinical associate professor of Internal Medicine in the College of Medicine, is the only female interventional cardiologist at Ohio State, a specialty of cardiology that performs procedures such as cardiac catheterizations and heart valve replacements. Until recently, when another female interventional cardiologist joined a local community hospital, Dr. Baker was the only one in Columbus.

Areas of medicine with fewer women tend to have less family-friendly training and require more hours on-call at night, Dr. Baker says. “When I attended medical school in the late ’90s, there was nothing built into the system that made you think you could take time off. There were a lot of night calls and a lot of time in procedure labs,” she says.

She loves what she does. Recently, Dr. Baker assumed a leadership position as medical director of Interventional Cardiology Services and the Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory at an Ohio State partner hospital, Memorial Health. But Dr. Baker says she and her husband made a lot of sacrifices for her career — including waiting until she was several years out of her medical training to have a child.

But the culture is changing.

Today’s cardiology fellowship at the College of Medicine is close to 40% female (the national average is 24%). Several women in the program already have children. They take time off for maternity leave and can schedule their time in the cath lab — where physicians wear heavy lead gear to avoid radiation exposure — so that it’s not during pregnancy.

Dr. Baker says she encourages female residents to speak up about their needs and not to feel pressure to wait to start a family.

“I’m very vocal when residents come to me, to let them know what it was like for me and encourage them to speak up. Don’t wait to start a family and don’t feel pressure. Saying that over time has helped residencies get into a family-friendly mindset,” she says.

Working to change expectations

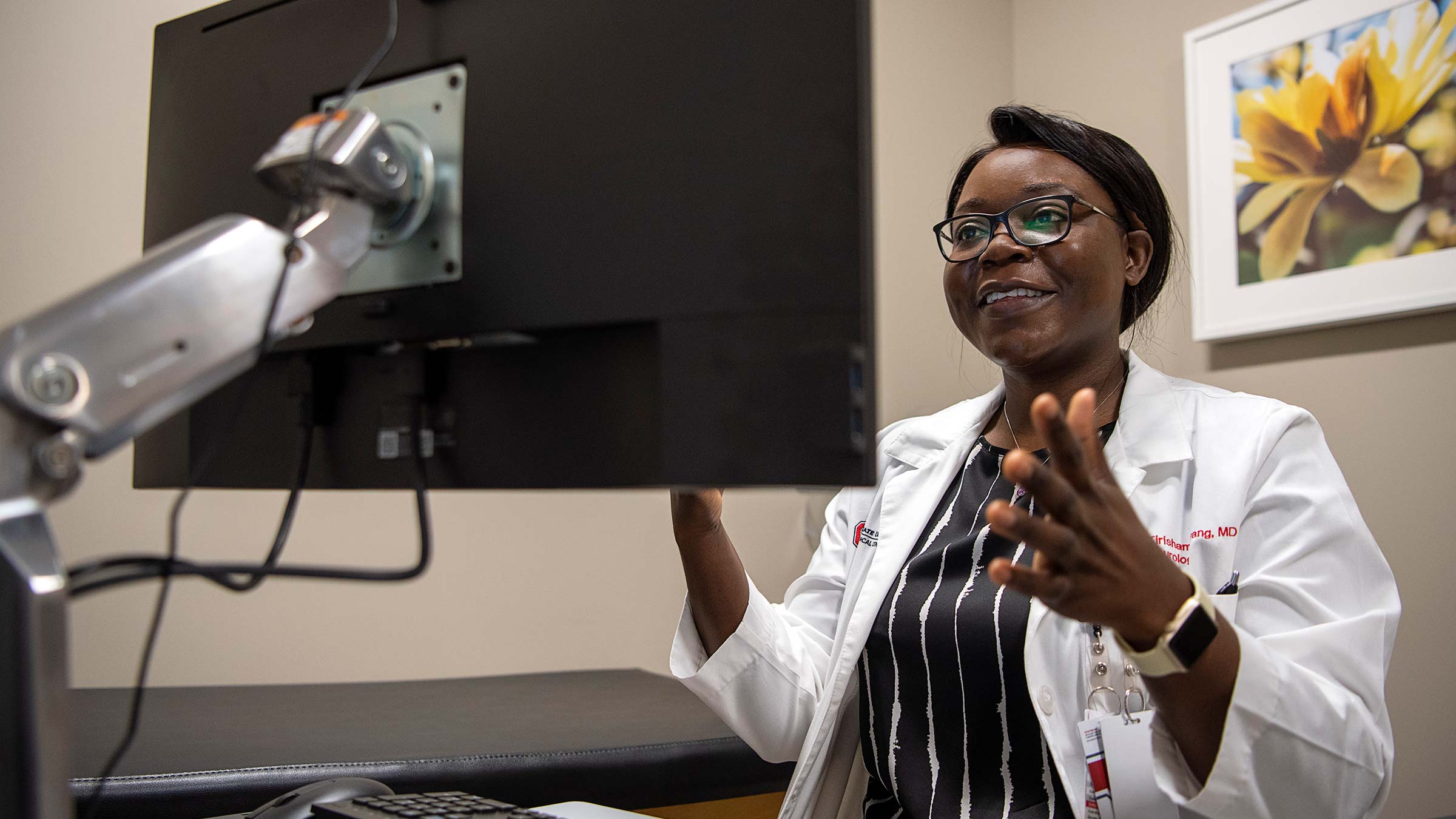

Tirisham Gyang, MD, clinical assistant professor of Neurology at the Ohio State College of Medicine, is also used to being the only woman doctor and the only person of color in the room.

“When I walk in the room to see a patient for the first time, sometimes they expect to see someone completely different.”

She tries not to focus on what others expect. “I don’t let that be something that’s at the forefront of my mind. I think about the value I have to offer.”

As a physician-scientist in breast cancer research, Dr. Gatti-Mays says it’s not unusual to be the only woman at the table.

“Sometimes it’s intimidating. You speak up, and everyone speaks over you. You have to be confident and speak even louder. It helps to have allies — both female and male — who can amplify your thoughts.”

Women in medicine offer a different perspective

Drs. Gatti-Mays, Gyang and Baker all agree that being a woman is part of what makes them great doctors. Dr. Baker says, “I’m a little more patient in listening. Patients don’t like to be rushed, and they want to tell their story.”

In cardiology especially, where women present with different symptoms than men, listening is key to excellent care.

“I see a lot of female patients whose symptoms have been pushed aside and told it’s not their heart. Women sometimes have the strangest presentation (of symptoms). I listen to their concerns maybe a little more,” Dr. Baker says.

“When you’re trying to solve a problem and you have diverse people, you get a better solution than if you had a monotonous group.”

Entering specialties with fewer women takes courage and fortitude. Dr. Gyang advises, “If you have a passion and an interest in whatever field, don’t let anything stop you. Don’t let the fact that you don’t see a lot of people who look like you in that specialty stop you. Don’t let countering voices make an impact on what you feel you’re meant to do.”

The pandemic was a setback for gender equity in science and medicine

While the number of female physician-scientists continues to increase, diversity was set back during the pandemic. Many of those with caregiving responsibilities, which disproportionately affect women and minorities, lost ground in areas of productivity, work-life balance and professional development. Some women paused or left careers.

“There was already gender inequity, and this has just been exacerbated. There’s a lot of work still to be done to reset the lost equity due to COVID-19,” Dr. Townsend says. She and others at the College of Medicine are taking proactive measures to promote equality and address gaps. That includes establishing best practices for hiring equity and inclusive hiring practices, as well as ensuring the processes for promotion and tenure are transparent. All faculty members who serve on hiring committees are also required to take training for implicit bias and diversity, equity and inclusion.

Female mentors are key to more women physician-scientists

Dr. Baker knows what she wishes were different in her journey to become an interventional cardiologist. She uses that to empower the cardiology fellows she teaches.

“Twenty years ago, I was not so comfortable asking for what I needed. I’m always pushing my fellows now. I’ll say, ‘Let’s go through your contract.’”

She mentors cardiology fellows of all genders and will encourage any women, especially, who show talent in the cath lab to pursue interventional cardiology.

For those times when her mentee is the only woman physician in the room, Dr. Baker advises her to speak up.

“Don’t hold back. Make sure you have a seat at the table. You should feel no different than a male when it comes to your work.”

Dr. Gatti-Mays says it’s important for all doctors, male and female, to have a team of mentors to support residents and fellows.

“It’s helpful to have a mix of both men and women. If you have a homogeneous team, you may lose an important perspective.”

How we can make room for more women in medicine

As hard as it can be some days to juggle leadership, research, medicine and family, Dr. Gatti-Mays says she wouldn’t want to do anything else. What she would change is the thinking around balancing having a family and working in medicine.

“I wish someone would have told me that you don’t have to choose. You can do it all — just like our male colleagues. Sometimes family or research or clinical care have to be the priority, but you can do it.”

Still, she says, work-life balance is a misnomer. “Really, it’s work-life juggling.”

Making it easier for women to enter and lead in every area of science, research and medicine means more than accommodating maternity leave. It means restricting meetings to business hours so physicians don’t have to choose between taking care of family and being present at work. And it means having supportive colleagues and supervisors.

Dr. Gatti-Mays says she’s been fortunate to have bosses and colleagues who’ve been supportive of her choice to build a family, but a lot of her female colleagues haven’t had that. For her part, Dr. Gatti-Mays tries to model for her resident team what it means to support women doctors. Now when she enters a room with students and a patient turns to the men instead of her, she resets the conversation by reintroducing herself, “I’m Dr. Gatti-Mays, and I’m the supervising doctor on the team.”

It’s a response that’s out of her comfort zone and took some practice. But she’s earned it.

We’re removing barriers to better health and wellness

See how Ohio State is elevating experiences and outcomes for every patient, employee, learner and community member.

Read More