Before Google and smartphones, before electronic medical records, when doctors carried manila folders into patient rooms, Aaron Clark, DO, was a young family practice doctor in rural Ohio.

On any given day, he might treat strep throat and rashes, sore backs and high blood sugar. He liked the variety.

In the early 2000s, Dr. Clark began practicing east of Columbus where the sick or injured had only two choices for care: a doctor’s office or an emergency department. Messaging a doctor online with a question or requesting a medication refill was several years away. So too were apps that could keep people aware of their heart rate, sleep quality, blood sugar levels and daily steps.

During Dr. Clark’s residency training, every couple of weeks a semi-truck carrying an MRI machine parked in front of the local community hospital. Patients who needed an MRI stepped into the truck, had scans taken, walked out and waited several days for grainy images. MRI machines were brand-new and expensive. Only large urban health centers had them.

“So, for many communities, the only way to access an MRI was the mobile unit hauled by the semi-truck,” Dr. Clark says. “Now I have an MRI 20 yards down the hall.”

Many of the technological advances Dr. Aaron Clark has seen in medicine over the past two decades have allowed patients to get better care.

Over the two decades Dr. Clark has been a doctor, he’s seen major scientific advances in the field of family medicine. In technology and medications, in the treatment for chronic diseases and cancer, in the focus on preventing illnesses and the recognition that housing, education, income, race and other factors influence how healthy a person is.

Health care for all

Dr. Clark’s aim has long been to help, especially people who can’t easily afford treatment.

He grew up in Columbus, attending Columbus public schools in the 1970s, when students were bused into schools to equalize educational opportunities.

As a young father in his mid-20s, still in medical school accruing heavy debt while his wife worked full-time, the family received federal assistance. They qualified for and received food through the federal Women, Infants & Children program, subsidized day care for their young children and federal payments that helped keep them afloat.

Though his time receiving public assistance was brief, it made him sensitive to his patients’ financial struggles to pay for not only health care but a nutritious, regular supply of food.

“There’s a birth lottery that happens,” Dr. Clark says. “Someone gets born into a set of circumstances, and that can define their journey in their lifetime. That doesn’t seem quite fair.”

Now, as chair of the Department of Family and Community Medicine, he’s dedicated to providing chances for people to be as healthy as possible.

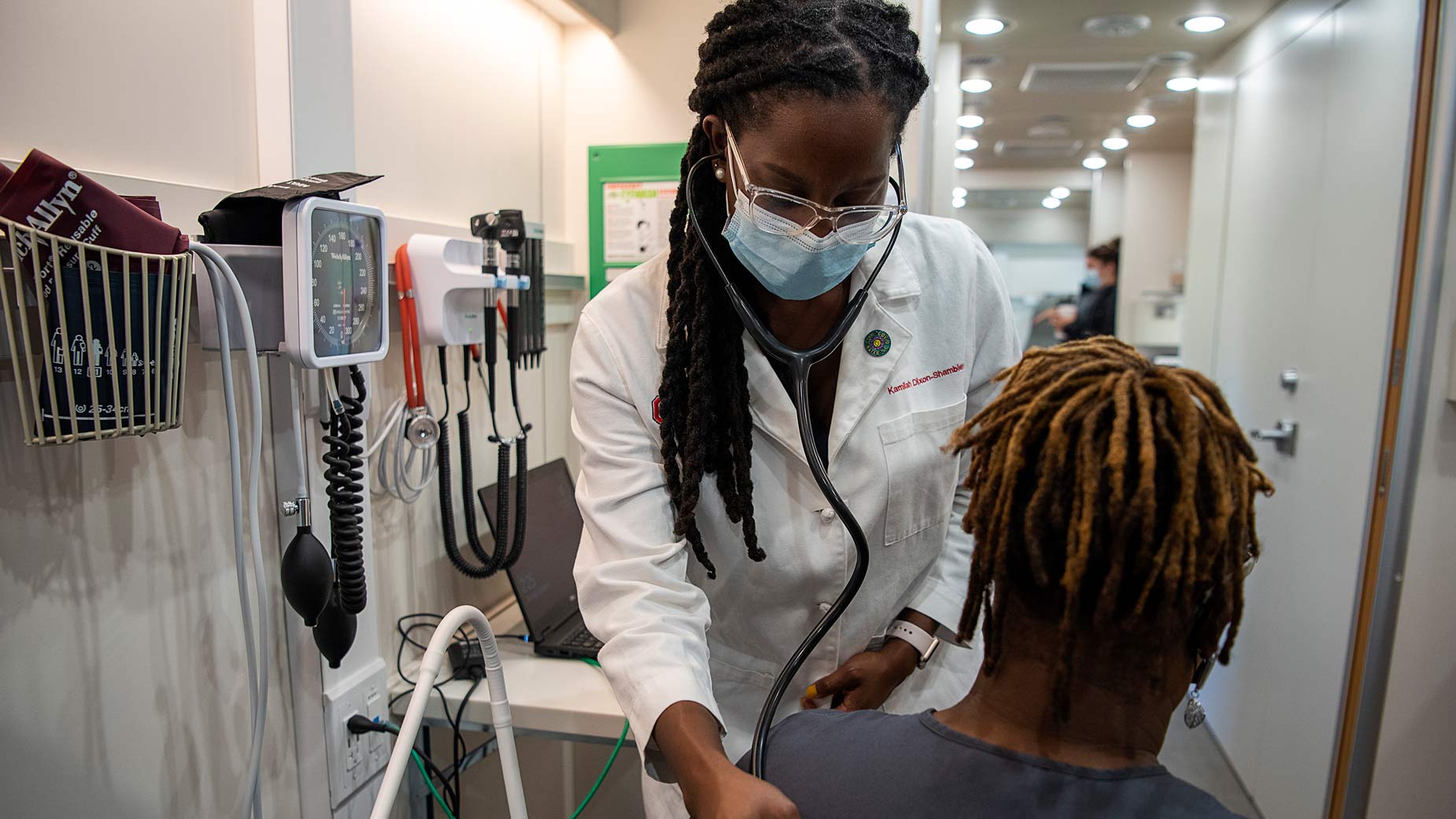

Over its 50 years of teaching doctors and treating patients, Ohio State's Department of Family and Community Medicine has evolved in how it cares for patients. Physicians treat people in refugee clinics and through a mobile unit that drives to parts of Columbus offering weekly primary and prenatal care visits, screenings and lab tests. Office space and volunteers are provided to several area free clinics.

“We’re reaching a larger portion of the community, including people who may not have been able to be treated in the past because of where they lived or the cost,” Dr. Clark says.

And patients wanting integrative medicine have a range of options from chiropractic care and therapeutic massage to acupuncture and Ayurveda.

The Community Care Coach offers primary care vaccines, physical exams and blood tests to Franklin County residents who may have otherwise gone without.

Treating chronic illnesses better

While medicine will always be about treating illnesses, Dr. Clark has seen the shift to focus on preventing illnesses. Annual screenings for blood pressure, blood sugar levels, body mass index, immunizations, exercise and good nutrition have all helped stave off some sicknesses and diseases.

Better and more medications also have allowed people to live longer. Among the more significant to Dr. Clark is the treatment of congestive heart failure. Decades earlier, only a few medications existed. Today, they’re numerous, helping extend the lives of people whose heart can’t pump blood well enough to give their body a normal supply.

Even just a decade ago, a cancer diagnosis was far less likely to come with the hope of surviving. And people with HIV, though still incurable, can manage the chronic disease with medication. Far less often, HIV develops into AIDS and turns fatal.

Dr. Clark considers this to be one of the more significant triumphs in medicine over the past two decades.

“HIV was feared, and entire communities were shunned and marginalized,” he says. “It’s no longer a death sentence. This is quite remarkable.”

Annual health screenings and visits with health care providers can go a long way toward preventing serious illnesses or treating them early on.

Empowering patients with health care technology

For Dr. Clark’s patients, health care apps have made a significant difference, especially for people with chronic illnesses.

His patients with diabetes used to track their blood glucose levels, poking themselves with a needle and testing their blood at certain times each day and recording the results. They’d bring their logbooks to appointments, and from those, Dr. Clark had to try to figure out the patterns of the spikes and dips of their blood sugar.

People with diabetes can now wear continuous glucose monitoring devices to see how their glucose levels change before and after they eat and exercise. The devices compile a patient’s data so Dr. Clark and the patient have the patterns clearly laid out.

“It allows people to see the cause and effect of their food choices,” Dr. Clark says. “That can help them make better decisions.”

Electronic records allow many doctors to easily share information on a patient. In the past, a separate paper chart was created for each doctor a person saw. One for the cardiologist, one for the family medicine physician, one for the Ob/Gyn, one for the endocrinologist.

By health care providers sharing all the same information, they can now view a patient’s health history and lab test results as well as all the medications they’ve been prescribed. That prevents patients from taking combinations of medicines that might be harmful.

With electronic records, an entire health care system can tell how well its diabetes patients are controlling their blood sugar, how many patients get mammograms and colonoscopies, and how healthy newborns are, Dr. Clark says.

New technology has also allowed people to be in closer reach of their health care providers. Patients can now communicate with their doctors more than only once a year at their annual exam. At any time, patients can send messages online asking a question or requesting prescription refills, a perk for patients and a challenge for medical staff whose inboxes overflow.

“We love getting our patients’ messages that they’re seeking our guidance and care,” Dr. Clark says. “But there is such a huge, huge amount of that we have to sift through.”

His hope is that, in the not-so-far future, artificial intelligence will help resolve that problem by assisting medical staff in sifting through and responding to messages. Artificial intelligence, Dr. Clark expects, may play more of a role in helping diagnose patients and determine risks of certain treatments.

But more than artificial intelligence, the success of medicine will always rely on the skill of medical professionals, and the trust they can develop with their patients.

“At the end of the day, the most rewarding part is being in the room with a patient that you’ve known over time, through their good and difficult times,” Dr. Clark says. “And being able to impact their life in a way that few people can.”