Inspired by her father’s battle, physician-scientist determined to stop glaucoma

Sayoko Moroi, MD, PhD, is developing new treatments to save more people from glaucoma-induced blindness.

David Moroi loved baseball, and he loved watching TV — slapstick comedy shows, wildlife programs, Bigfoot documentaries and especially the Little League Baseball World Series matchups, which he made sure he never missed.

His daughter, Sayoko Moroi, MD, PhD, remembers her father struggling to see those programs and games due to his glaucoma and retinal condition. And it was his determination and positive attitude despite those challenges that inspired her to specialize in ophthalmology, with a focus on glaucoma.

“My motivation and truly my inspiration for choosing glaucoma was because, essentially, my father developed blindness.” Sayoko Moroi, MD, PhD

“He still saw 20/20, but he met the legal criteria for blindness from glaucoma,” says Dr. Moroi, who holds the William H. Havener, MD, Chair in Ophthalmology Research at The Ohio State University College of Medicine and directs the Havener Eye Institute.

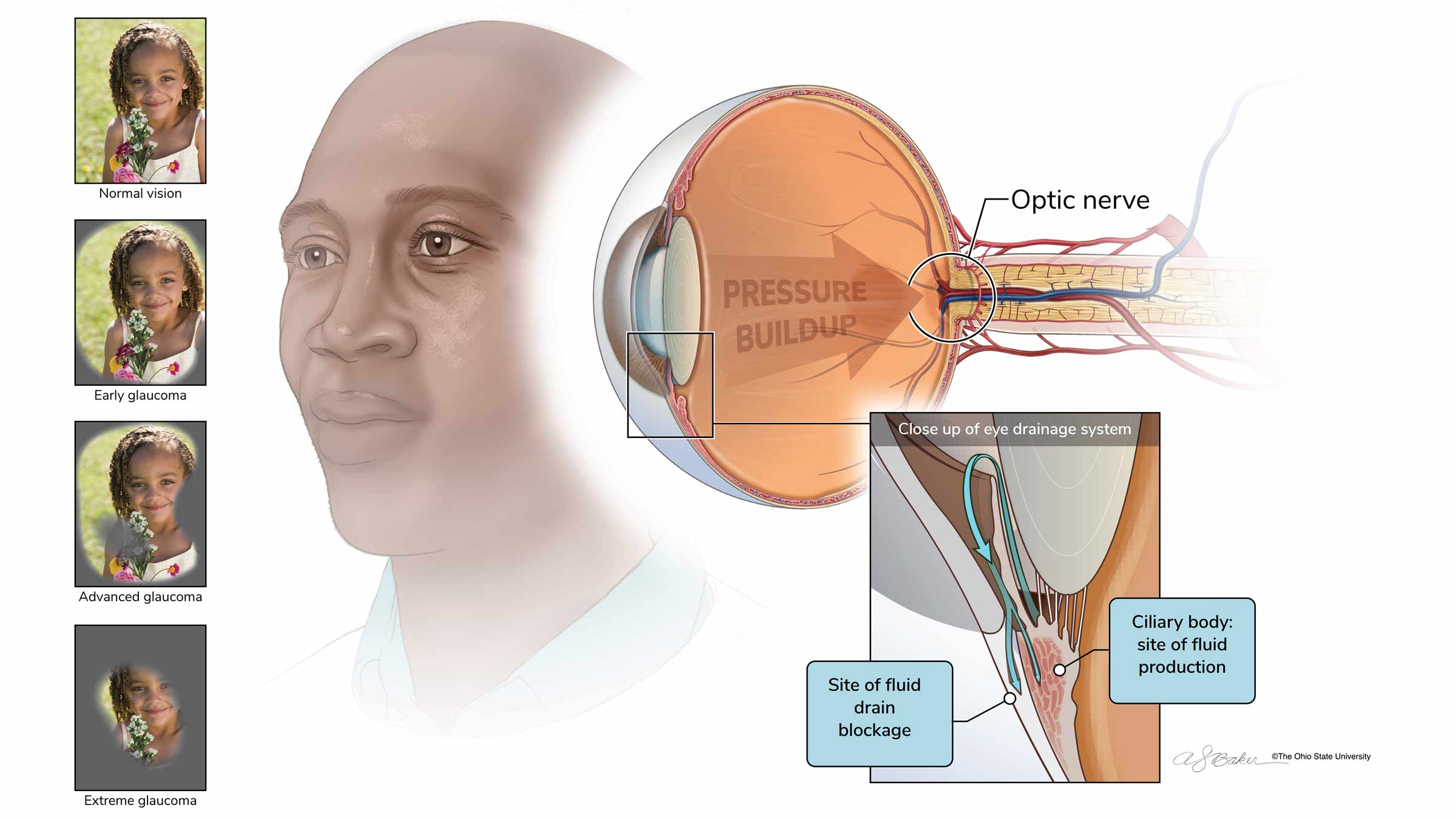

Glaucoma limits peripheral eyesight and can severely impact the ability to see, even in people with otherwise 20/20 vision. Dr. Moroi’s father only saw small glimpses of the world around him. It was as if he was looking through a drinking straw.

His love of sports didn’t stop at baseball — he’d catch just about any sports game on TV. His daughter, herself a Blue Devils fan since her undergraduate days at Duke University, smiles as she remembers him always calling to remind her, “Sayoko, Duke’s playing basketball right now!”

Today, her thoughts of her father and his struggle with glaucoma are never far away.

Photos of her late parents are among the items she keeps on display in her office as she continues to pursue her aspirations. They look on as she fulfills an active roster of clinic appointments and eye surgeries, all while running an impressive amount of research programs that promise to revolutionize the field of glaucoma treatment.

Searching for better glaucoma treatment options

Glaucoma is a leading cause of vision loss and blindness in both the United States and the world. The incurable disease is caused by damage to the optic nerve in the back of the eye. A main risk factor is increased eye pressure, which can place stress on the nerve, often caused by a problem with the eye’s drainage system.

According to the most recent data from the National Eye Institute, more than 2.7 million people in the United States had glaucoma in 2010. The agency has predicted that nearly 4.3 million Americans will have glaucoma by 2030 and that nearly 6.3 million will have glaucoma by 2050. Prevalence increases with age.

When explaining options to treat glaucoma, Dr. Moroi likens the system that regulates eye pressure to a plumbing system: There’s a faucet of fluid production and there’s a drain. Treatments either help decrease the flow of the faucet or unplug the drain.

Current treatment options include medication eyedrops or pills, laser therapy and incisional surgical procedures with the goal to lower eye pressure. Dr. Moroi says research is essential to make advances in treatment and cures, and federal funding, private foundations and philanthropy are the means to makes these discoveries

“Many people will tell you that if they lost a significant amount of vision, they would be devastated. In order to secure research funding to make discoveries, it is essential to write a strong pitch that is reviewed favorably and then funded for research,” says Dr. Moroi.

Through collaboration, the Ohio State Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences was recently awarded a five-year, $2.85 million National Eye Institute P30 Core Grant by the National Institutes of Health. This research award will be used to bring together vision scientists across the Ohio State colleges of Medicine, Optometry, Veterinary Medicine, Engineering and Arts and Sciences. “The Ohio State University Vision Sciences Research Core Program will serve as a bridge to help funded investigators and to foster collaboration across disciplines by providing access to shared state-of-the-art resources, services and training that are essential to research activities.

Through separate research work in her area of expertise, Dr. Moroi’s hope is to decrease the amount of glaucoma-related blindness. With a combination of research methods, she’s working with other teams on projects designed to customize each patient’s glaucoma treatment plan. This is done by using genetic information, eye physiology, imaging data and other factors specific to a patient, including social determinants of health — the many conditions that affect a person’s health, functioning and quality-of-life outcomes and risks. This broad team-based approach is known as precision medicine.

Her work will allow glaucoma specialists to move beyond antiquated ways of assessing risk and effectively target care, says Andrea Sawchyn, MD, director of the Glaucoma Division in the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences.

“And that will save us time, because we’re not going to have to go through months of trying different medications,” Dr. Sawchyn says. “And if we’re able to save that time, we can potentially save more vision and obtain a better outcome for the patient in the long run.”

Dr. Moroi’s current research projects seek to make that happen in three main ways:

- Using new technologies to gather more eye pressure measurement data to assess large eye pressure variations

- Examining the eyes’ plumbing system to determine the inflow and outflow systems to understand optimal medications to lower eye pressure

- Mapping drainage pathways to determine the most appropriate surgical technique for each patient

Improving data to save more vision for patients with glaucoma

Eye pressure is the only treatable risk factor to slow glaucoma progression, which is measured through peripheral vision tests and images of the optic nerve, typically taken during periodic doctor visits.

“We’re very much still limited to a clinical care model of being comfortable and satisfied with three to four eye pressure measurements during the year. With this current model, people are still going blind from glaucoma,” Dr. Moroi says.

Newer technology allows patients to gather their own pressure data at home through use of a handheld device with a disposable tip that gently taps the eye to collect pressure data. More comprehensive eye pressure data collection in the real world gives physicians and researchers insight into potentially 24/7 fluctuations in eye pressure, response to treatments and adherence to medications. Dr. Moroi seeks to determine whether this eye pressure fluctuation data will help improve patient outcomes by comparing data from stable patients with data from patients who are losing vision.

One goal is to use the more robust eye pressure data in partnership with her department colleague, X. Raymond Gao, PhD, to compare patient readings with their genetic sequences. This collaborative research will provide genetic signatures that relate to patterns of those patients who have high pressure fluctuations, average pressure fluctuations or low pressure fluctuations.

“So, what am I hopeful for? And what do I share with the patients? I inform them that we now have better technologies to assess their pressures in the real world,” Dr. Moroi says. “Once we understand and have their data, we can better control their eye pressure outcome. And that definitely has an impact on decreasing vision loss from glaucoma.”

Studying glaucoma treatments to ‘fix the plumbing’

To further determine why certain medications might work better for some than others, Dr. Moroi is studying the glaucoma drugs’ effect on the eyes’ plumbing system to understand the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of patient variations in treatment response. She and her multi-center team, which includes Mayo Clinic and University of Nebraska Medical Center researchers, have established a dataset in more than 125 normal health controls, and have begun to collect the same data in more than 100 patients with glaucoma. These anticipated results will provide answers that will eventually allow physicians to prescribe the right medication to the right person without the current trial-and-error process.

“Once we get the results, we’ll be able to understand and answer ‘what are the main drivers for drug response in healthy persons?’ and then, ‘how is it different in patients with glaucoma?’” Dr. Moroi says. She leads this collaborative project that’s funded by the National Eye Institute.

Precision glaucoma surgery

There are many approaches to incisional surgery for patients with glaucoma who are intolerant of medical therapy and have failed laser therapy. As a surgeon, Dr. Moroi knows there can be a lot of trial-and-error approaches. She seeks to change that by using imaging to map patients’ drainage pathways and determine what surgical approach may work best by either targeting this drainage pathway or bypassing the drain if the individual patient’s drain is nonexistent or “closed.”

She initiated this research at the University of Michigan about a decade ago when she worked there and has launched this research at Ohio State using a new-generation imaging instrument called swept-source optical coherence tomography angiography. The device allows for wider, deeper, more detailed images, which Dr. Moroi processes with the help of engineer collaborators. The goal is to determine which type of surgery is most appropriate for each patient or, if these drainage pathways are too damaged, how they can be bypassed.

“And then I hope, with the right partners here, that we could perhaps even consider regenerative treatments for patients with glaucoma if their drain pathway is so severely damaged,” Dr. Moroi says.

Guidance and a calling

Dr. Moroi’s parents, David Moroi, PhD, and Kazue Moroi, both earned degrees in Japan before immigrating to the United States. David Moroi arrived on a federal Fulbright Scholarship and earned a doctorate degree in physics and quantum electrodynamics at Johns Hopkins University in 1959, the same year the couple wed. Kazue Moroi, who held a degree in traditional Japanese studies, later joined him in Ames, Iowa, where he was performing postdoctoral research at Iowa State University.

The couple eventually settled in Kent in northeast Ohio, where they raised a daughter and two sons.

Dr. Moroi says her parents pushed their children to excel, but also helped them find balance to enjoy life, with many camping trips to National Parks. (One of Dr. Moroi’s early dreams was to be a National Park ranger.) Her mother also trained her daughter in many manual skills and art, such as Japanese tea ceremony, doll making and origami sculpture, so surgery was a natural fit. One of Dr. Moroi’s brothers, who’s mechanically inclined, is a mechanical engineer, and her other brother, who’s artistic, is an architect.

“My parents really helped support us to find what our natural skills are and helped guide us with education to really build upon those.” Sayoko Moroi, MD, PhD

“So, I and my brothers, we don’t just have a job, we have a profession with a calling and what we like to do. And not everybody has that. I feel very fortunate.”

Dr. David Moroi began having difficulty with vision when he was in his 50s. At the time, his daughter was pursuing her advanced degrees at Ohio State, and it was there where he was diagnosed with glaucoma.

“It was very scary, as he was driving. And then my brothers and I finally had to say, ‘you know, Dad, you shouldn’t be driving anymore,’” she says. “His central vision in one eye was very, very good. And he — as a typical Asian immigrant — never complained. He just kept going.

“So, I really admire him for not giving up or not getting depressed, because then later on, he had a retina issue that made him legally blind in the other eye.”

Lifelong relationships

Dr. Moroi is a brilliant physician with a genuine interest in both the field of ophthalmology and the human condition, says Lorna Gonsalves, PhD, a sociologist who was a patient of Dr. Moroi’s in Michigan and continued seeing her at Ohio State, a 2.5-hour drive from her northwest Ohio home.

She calls Dr. Moroi a rare health care provider who understands the importance of attending to a patient’s entire system, not just the eyes.

“She is truly remarkable. I see her not just as my doctor, but as someone who is going to be advocating for me on many fronts,” Dr. Gonsalves said during a visit in spring 2022. “Sy is a wonderful human being — a true healer in every sense of the word.”

When patients first come to Dr. Moroi for consultation after a glaucoma diagnosis, they’re fearful, often having read up on the disease and learning that it can lead to blindness.

“As we all age, we realize what changes happen in our bodies. And people become more and more self-aware of what would happen to their life if they became vision-impaired.” Sayoko Moroi, MD, PhD

The value Dr. Moroi places on treating the whole person is evident in her support of building the department’s social work team to provide assistance to patients who may experience anxiety or depression due to potentially blinding diagnoses, says Dr. Sawchyn.

“So, when we see someone struggling — because they’re losing independence, they’re losing their ability to get to and from their medical appointments, because they can no longer drive — we can reach out to our social work team to start some foundational emotional support while we work on getting that patient into a therapist,” Dr. Sawchyn says.

Amit Tandon, MD, a clinical professor of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences in the Ohio State College of Medicine, has known Dr. Moroi professionally for about 18 years and calls her “a perfect combination of intelligence, camaraderie, leadership and, most importantly, caring.”

“She’s very genuine,” Dr. Tandon says. “And I think patients see that.”

Advancing care, overcoming challenges

Dr. Moroi is optimistic about the possibility of discovering new treatments through research and heartened by the promise of new imaging, new technology and surgical techniques.

Ophthalmology is the field that achieved the first FDA-approved human gene therapy, in December 2017, for a condition called Leber congenital amaurosis, a rare blinding disease diagnosed in newborns and young children.

“Children would uniformly go blind, but now there is hope for their parents and the child that gene therapy can change the course of this blinding disease. Translating the basic genetics from the lab bench to the operating room and clinic is really amazing,” Dr. Moroi says.

“I am proud that ophthalmology is at the forefront for a number of discoveries and life-changing interventions that improve a patient’s quality of life.”

She says she’s achieved success by not giving up, even when disheartened by denied grant applications, and she’s grateful for her patients.

“I let them know that patients are my inspiration for research. Through research, I am trying to improve outcomes. However, I explain that the research results may not directly affect the patient, but future generations’ outcomes. The patients understand, and I am very blessed in getting support for research,” she says.

Dr. Moroi also understands the challenges of being a woman and a person of color in the medical field and considers herself to have been fortunate.

“My approach and attitude are such that I will keep working and find allies, and certainly mentors, who will help me along the way,” she says. “Have I sensed discrimination and bias? Yes, I have, but not in a way that I let it make me angry or frustrated. I would just keep going.”

Eyes as a window to overall health

In the future, Dr. Moroi seeks to expand research showing how eye health and vision pathways offer a key to a person’s overall health and to healthier aging.

The vision pathway to the brain is a relatively short pathway — a very easy, accessible pathway to analyze, Dr. Moroi explains. And the retina is the only place in the body where clinicians and researchers can physically see what’s going on in the blood vessels, which could reflect what’s going on with blood vessels in the brain and major organ systems.

Such research could offer insight into high blood pressure's impact on age-related falls, changes in cognitive function and dementia. Further, Dr. Moroi has begun a pilot collaboration with the Ohio State Division of Maternal Fetal Medicine to determine whether optic nerve and retinal blood vessels can offer a key to improving outcomes for pregnant people with preeclampsia, which impacts both the parent and baby.

“Nowhere else in the body, except through the retina, can we understand the rest of our body,” Dr. Moroi says. “It is truly the window to our health.”

Ready to learn more about eye care?

Ohio State's ophthalmology team provides comprehensive care backed by one of the nation's leading academic health centers.

Expert care starts here