‘There’s no safer place in the world’: Inside the surgical intensive care unit

Mother of motorcycle crash survivor finds unexpected hope, healing with veteran team of surgical ICU nurses

There was no hope.

As the ambulance sped away, Amy Landacre had seen the pile of crumpled black and orange metal that was once her son’s motorcycle. At the local hospital, she’d heard the doctor’s honest “probably not” when she asked if Cameron was going to make it.

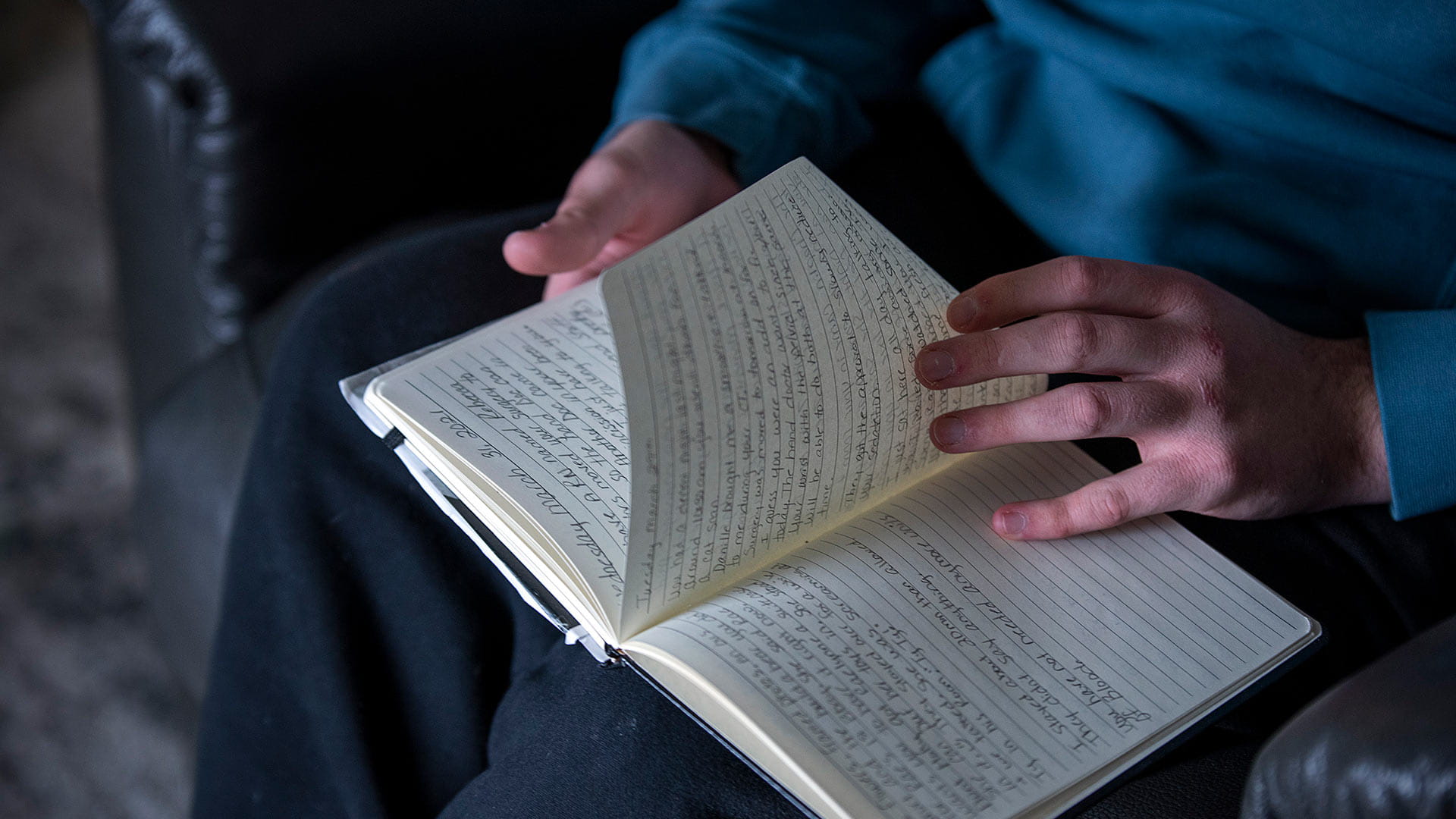

More than two years later, the page in the journal Amy started after the crash is dated — March 23, 2021 — but otherwise blank. She hasn’t been able to fill in the details. It’s just too hard to remember the night her then-20-year-old son was flown by a medical helicopter to The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, the night she and other loved ones waited an hour, two hours, three … finally almost six hours until the surgeon finished his work.

Cameron was alive. Barely.

Andrew Young, MD, the on-call trauma surgeon when Cameron Landacre arrived at the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, had seen injuries like Cam’s before and knows motorcycle accidents can be particularly devastating. However, his patient had age on his side and had been wearing a helmet.

“I would say if he didn’t have the helmet, he wouldn’t have survived,” Dr. Young says.

After losing control of the new motorcycle, Cameron had been flung into a cement pole and suffered several broken bones, damage to his liver, kidneys and colon, and a brain injury. He’d lost a massive amount of blood.

Cameron’s mother was finally able to see him in the Surgical Intensive Care Unit (SICU), where there would be more waiting as he lay hanging onto life in a coma. His father and younger siblings left the SICU after telling Cam they loved him. The COVID-19 pandemic meant it would be weeks before they’d be able to visit him again.

Veteran surgical ICU nurses bring ‘credibility and confidence’ to vulnerable patients

Cam became the newest patient in the 38-bed SICU, a place where patients recover — sometimes for weeks or months — following surgeries for major injuries, significant burns, unforeseen complications and transplants that might involve multiple organs.

In the SICU, nurses keep a constant eye on patients and the centralized monitors that display their vital signs. But no one quite seems to notice when a mother tests the limits of visiting hours, stealing a few extra minutes saying goodnight to a son who might not make it to morning.

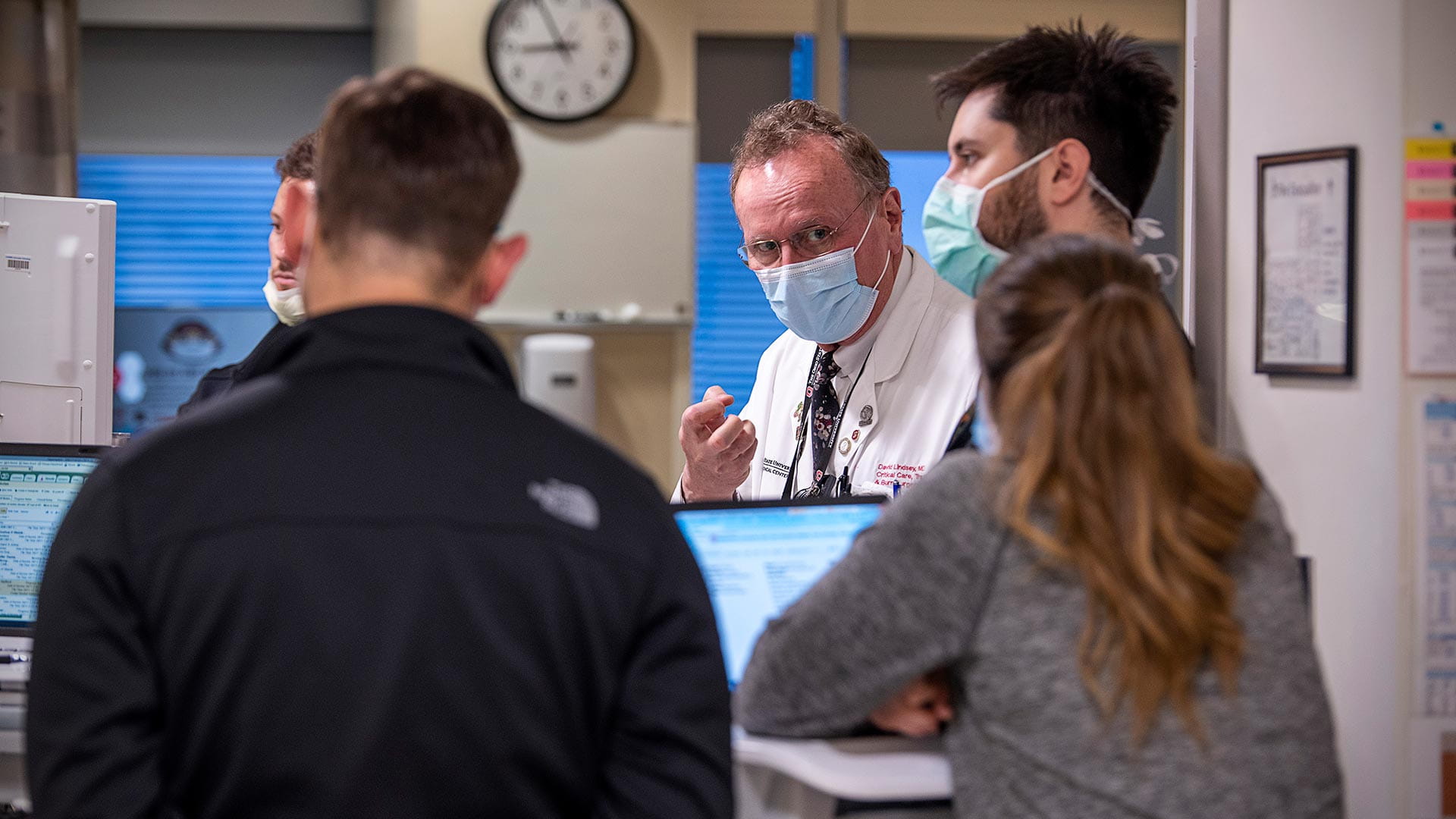

It’s one of several units providing intensive care in The Ohio State University Health System, where a veteran crew of nurses with a diverse critical care set has worked for decades. They’ve been exposed to a vast array of medical conditions, are trusted to give their input on cases and are often called upon as resources by others throughout the medical center.

“Our nurses have credibility and confidence,” says Kendra Stephens, BSN, MBA-HM, RN, the unit’s nurse manager, who’s worked in the SICU for 20 years. “They speak up in the best interest of their patients and work really hard to get them back to their lives.”

The veteran nurses also serve as role models, teaching critical thinking to newer nurses on the unit, where the intensity of the work means nurse orientation runs at least 20 weeks.

A mother’s unwavering dedication

Each day for the next three weeks, Amy Landacre sat at Cameron’s SICU bedside as the room filled with balloons and artificial flowers, the only kind permitted near vulnerable intensive-care patients. She made the nearly 40-minute drive home to Marysville every night, sometimes sleeping in her son’s sweatshirt to feel closer to him.

Cam was receiving blood transfusions, dialysis treatments and had a special catheter called a bolt placed just below his skull near his brain to gauge pressure. He faced several surgeries — to repair broken bones, to place pins in his back to stabilize his pelvis, to save a kidney, to repair his colon, to treat a blood clot in his thigh.

In his room was a photo of his daughter Raelynne, then 2 years old, and another of supporters gathered at a park holding signs reading “We Love You Cameron,” “Keep Fighting Cam,” and one tapping into his sense of humor: “Buy a Huffy Next Time.”

With pandemic protocols in place, the photos would have to do. Mom was the only visitor permitted to see Cameron during his stay.

But she never felt alone. Each nurse tends to have just one or two patients during every shift, and many got to know Amy well. They got to know Cameron, too, as Amy talked about his favorite music (country and rap), told him jokes and listened to a comedy e-book she thought he’d like.

Nurse Ryan Biederman, RN, BSN, CCRN, has an affinity for tattoos in common with his patient and remarked that Cam would have to get a new tattoo representing his latest battle when he was back on his feet.

Another nurse promised to pray for Cam when she left for the day: “She mom’d you! Saying Ohh Honey I know this hurts,” Amy wrote in her journal.

Nursing staff bonded by toughest of situations

Biederman, a 24-year nursing veteran who floats between various critical care units, appreciates days in the SICU due to its collaborative nature. “Everybody just works together — like everybody,” he stresses.

He recalls being in the unit in 2017 when staff tended to patients injured when a ride malfunctioned at the Ohio State Fair. “The teamwork was just mind blowing,” Biederman recalls. “Everybody felt they had their role.”

Denette Steele, RN, BSN, CCRN, assistant nurse manager, has served in the SICU 30 years, learning something new every single day — it’s a challenging place to work, she says, and you see things you’re told in school that you’ll never see.

In the SICU, Steele adds, everyone looks out for one another.

“The situations we are in together can be so difficult, that we are bonded as a staff in a very different way,” Steele says.

There’s always someone to bounce ideas off or to help when things get intense.

“It’s a very hands-on, very helpful team,” Steele says. “I always say you never feel alone out there, which is important. These patients are very sick. Even the patients who do not seem sick initially can deteriorate very quickly.”

The nature of the work means nurses in the SICU can be affected by the suffering they see every day, and they know that most people would find it difficult to experience what they experience.

Cautious optimism with improvement

As the days went by, Cameron started to take a turn for the better, though he still faced ups and downs. He no longer needed kidney dialysis. The incision in his stomach was healing well, but he had an infection. Brain pressure levels became normal, brain bleeds had improved and he’d had no seizures. “Another win, Cam! Keep it up!” Amy wrote March 31.

Doctors planned to start reducing the amount of sedatives being administered. Amy was pleased, but hope remained elusive amid her anxiety over questions about the extent of brain damage. Would her son know her? Would he be able to feed himself, walk or talk?

Then, Cam slowly started to move. First his finger. Then his neck and eyes, then his toes. He squeezed a nurse’s hand to indicate “yes” he was in pain and held his mom’s hand tight.

“Cameron, you have the whole staff looking out for you,” his mom wrote April 5. “I want you to know that!”

Friday, April 9: Cameron starts the day giving a nurse a thumbs-up. That afternoon, he’s taken off the ventilator.

He’s breathing on his own.

Those who have cared for Cam are in partial disbelief. “Most of the ICU team slowly started stopping in to say ‘Hey, He’s off!!’” Amy writes. “They are all checking on you!”

She finally dares to hope.

Two days later, Cameron says his daughter’s name, and four days after that, Amy packed up his things to move him out of intensive care and to the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center Brain and Spine Hospital.

Ahead are weeks of recovery, and plenty of setbacks, but her son is going to be OK.

Looking back, Amy calls the time spent in the SICU a great experience.

“I could tell the team cared for him, without knowing him. It didn’t seem like they were just doing a job. It felt like they connected with him,” she says. “They worked so hard on him, and they did such an amazing job.”

Celebrating the wins

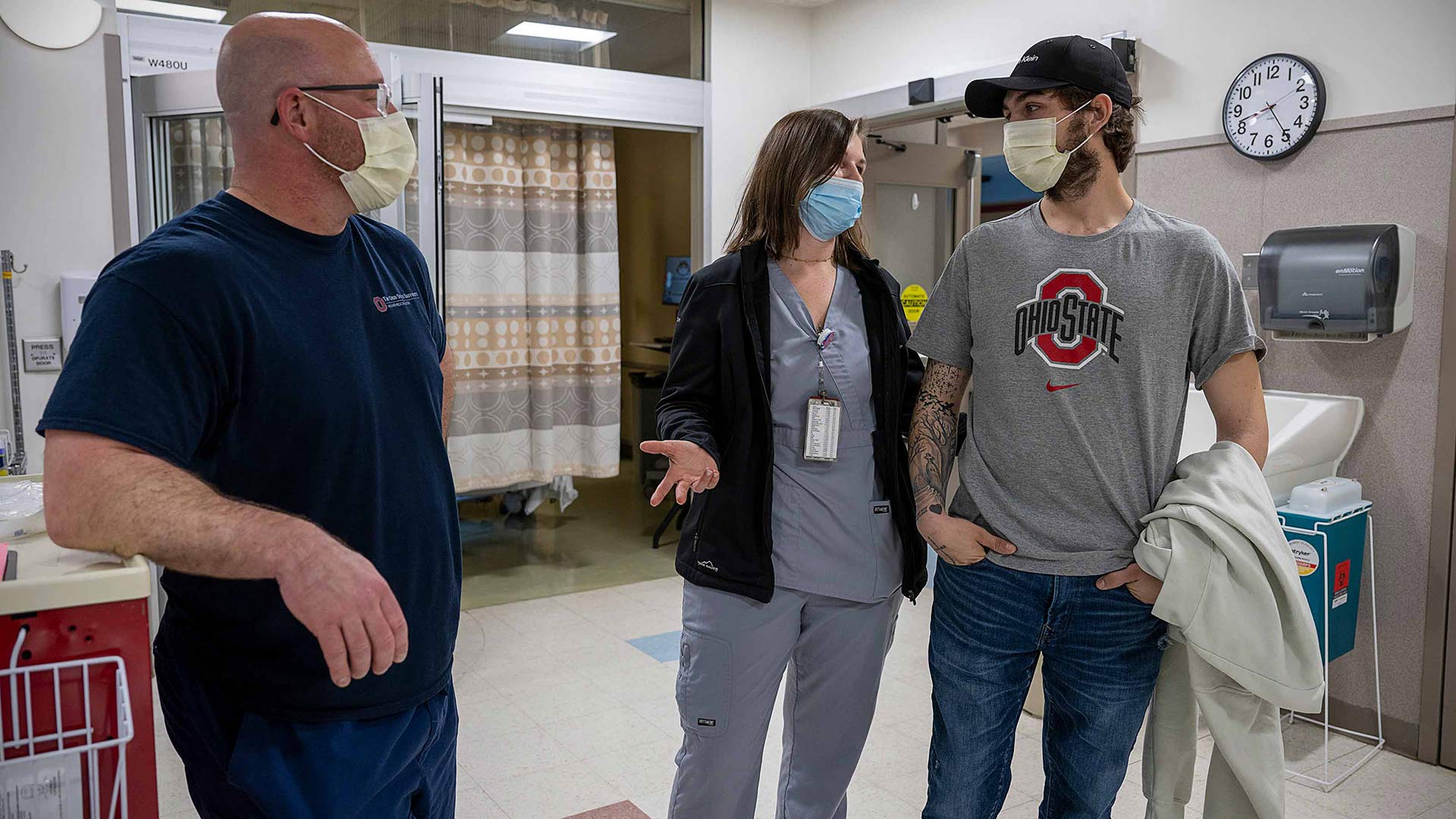

Physical therapist Ashley Salter, PT, DPT, and occupational therapist Sarah Shatto, MS, OTR/L, part of the SICU team, began treating Cam while he was still using a ventilator.

With the extent of his injuries, they say, it’s remarkable that he bounced back so quickly. It wasn’t without pain, but Cameron was determined, doing everything they asked of him.

In the SICU, teamwork and trust are the keys to success. And it’s meaningful, Salter says, to celebrate even little wins together. One of those wins came the day Cameron put on a ballcap himself, one of the first functional things the therapy team was able to prompt him to do.

“That was a huge thing,” Shatto says, “because that was him — to see his personality come out.”

Dr. Young calls Cameron’s recovery phenomenal and says the SICU is the only place for patients who need such specialized care.

“There’s no safer place in the world, so to speak. If you’re sick, that’s where you want to be,” Dr. Young says.

“He had just an enormous team, but it comes down to the SICU, the nurses at the bedside, who are the gatekeepers. The SICU nurses are checking everything, every single day, every single minute. And without that, any little thing could have gone wrong with this patient.

“Around the clock, they are on it, and that is really what gets these patients through.”

Showing appreciation for a lifesaving team

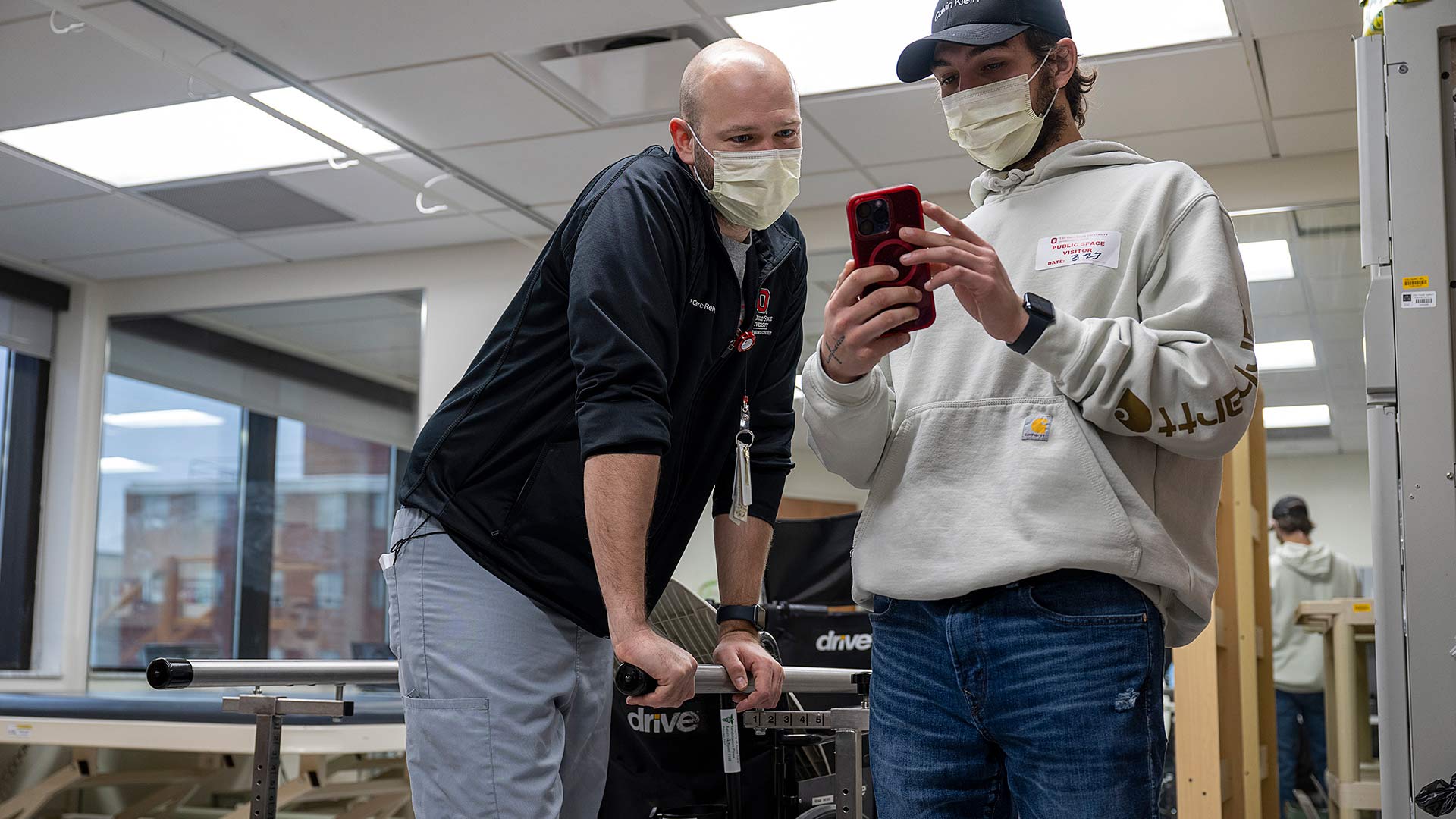

In the Ohio State Brain and Spine Hospital, Cameron continued to recover as therapists helped him first retrain his body to sit up in bed, and eventually walk again. By May 6, he’d progressed enough to be moved to the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center Dodd Rehabilitation Hospital.

That same day, SICU staff were shocked by an unexpected visitor. Cameron, pushed in a wheelchair by his mother, stopped by with doughnuts and thank you cards. About three weeks later, when he returned to say goodbye, he was met with tears and a caution against ever getting on another motorcycle.

It took sometimes painful and difficult therapy to get there. But, two days later, Cam was ready to put it all to good use, getting into a car to go home. Before the departure, Amy had a few words for the team who pulled Cam through: “Thanks for saving my boy.”

His first tattoo after recovering hearkened back to Biederman’s advice. It tells him to “Never Give Up” whenever he sees his chest in the mirror.

Amy and Cameron Landacre made several more visits to the SICU, including to mark the first and second anniversaries of his crash, showing the team his progress as he went back to work as a plumber and got back into shape at the gym.

They want the staff to know that the work they do makes a difference, to never give up hope.

A spark for the future

Many patients, like Cam, don’t remember their time spent in the SICU, or may not want to return to a place where they experienced the worst time of their life. The care team often never finds out how a patient fares in the long run.

Seeing success in patients like Cam “gives you that spark” and hope for good outcomes in the future, Salter says.

Craig Henman, RN, BSN, PTA, who worked with Cam as a physical therapist assistant during his stay at the Ohio State Brain and Spine Hospital, says it’s been the highlight of his career. He took Cam smoothies after he transferred to Dodd Rehabilitation Hospital, and Cam keeps him updated through social media and occasional visits.

“He doesn’t remember everything that happened during his stay or even all of the people that helped him along the way, but that doesn’t stop him from recognizing he received a lot of crucial care over those long weeks,” Henman says. “Each team played an integral part in his care, and it led to Cam having a success story that he can tell for years to come.”

A son’s gratitude

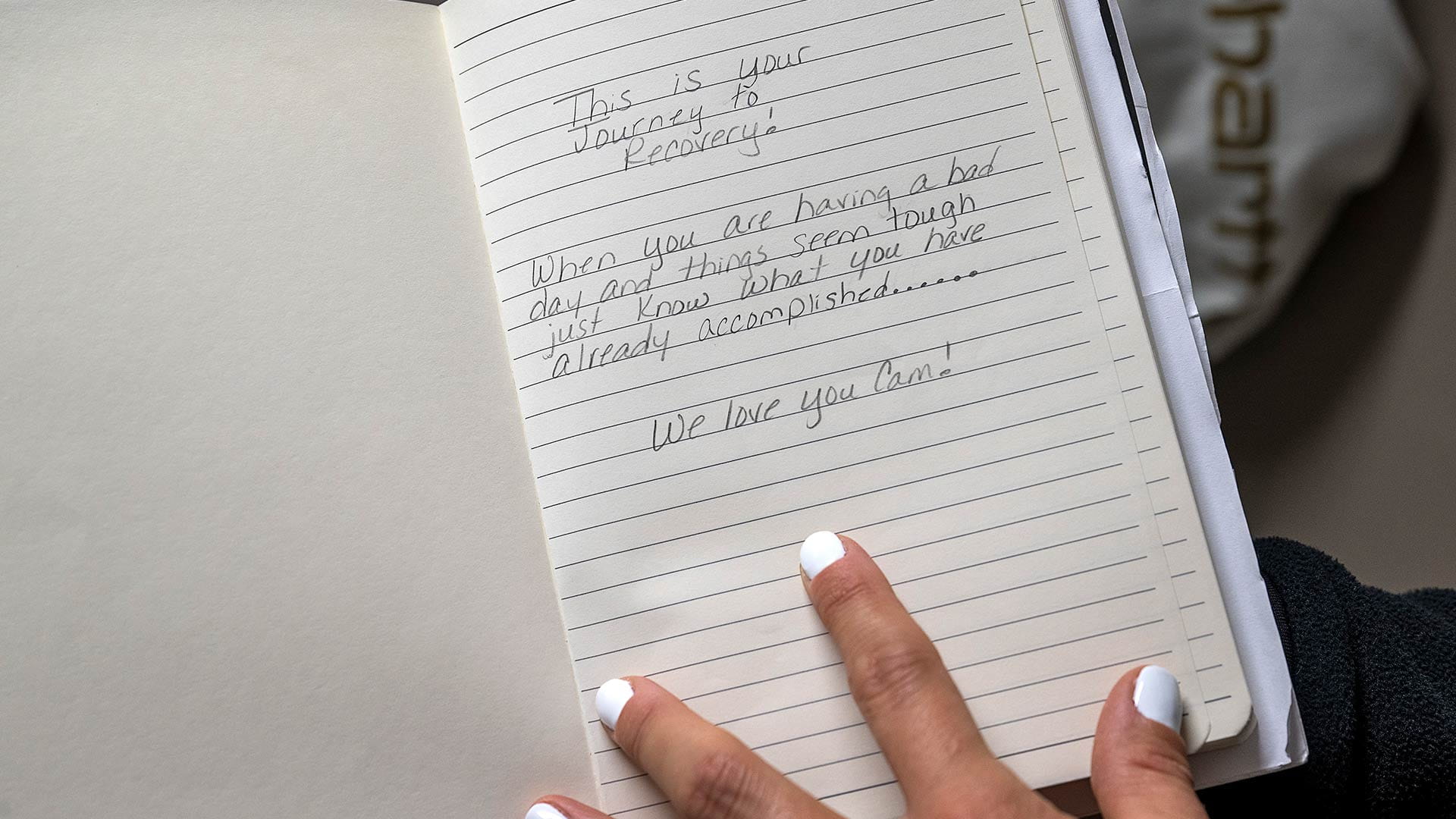

Amy Landacre’s journal kept her hands busy as she watched and waited for her son to recover. She also wanted him to have it to fill in the blanks in his memories.

“I wanted him to see that journal if he was having a bad day, to just to be like, ‘This is what you've already accomplished,’” Amy says.

Cameron waited several months after his hospitalization before cracking open the small book. He wasn’t shaken by the details of his ordeal, but was touched by the scope of what his mother went through and what she did for him.

“That was the only thing that kind of made me tear up — seeing what my mom was mentally doing and processing,” he says. “It was really the only thing that did it.”

When you give to The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, you’re helping improve lives

We’re committed to making advancements in research, education and patient care that will have an impact throughout Ohio and the world.

Ways to Give