Looking inside the brain to uncover the origins of mental illness

Psychiatrist K. Luan Phan, MD, uncovers the link between the effects of trauma and stress on the brain to inform a new understanding of how mental illness develops.

K. Luan Phan, MD, fell in love with the brain when he watched his pathology and anatomy professors slice one into sections in front of him. Phan and his fellow medical school students had studied the intricate connections and fibers responsible for sending electrical signals and pulses of chemicals across the brain’s landscape. They learned how these signals set off sensations, movements, language, memory, behavior and even the roots of our consciousness. For Phan, the dissection brought the brain to life.

Later, when he was able to visualize the complexity of the dissected sections of the brain by viewing images captured from magnetic resonance imaging and electroencephalogram, he knew his fascination with the complex organ would inform his lifelong work to understand the origins of brain-based disease.

Phan transitioned from the classroom to the clinic and soon began a psychiatric rotation. He met his very first patients, many of whom were veterans of the Vietnam War. They suffered from anxiety and depression, intrusive traumatic memories and elevated stress levels. Their symptoms remained, despite the decades that had passed since they had seen combat. Like soldiers of previous wars, they too had witnessed the deaths of fellow soldiers and civilians while fighting an enemy that was, at times, ill defined. They too held onto this trauma and remained silent because talking about it was painful and besides, who in their lives would ever be able to understand or relate?

K. Luan Phan, MD, professor and Charles F. Sinsabaugh Chair in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health at The Ohio State University College of Medicine, chief of psychiatry services for the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center

However, this particular group of veterans had the added burden of lingering shame, guilt and social isolation. Phan explains that Vietnam vets were met with less acceptance and increased scorn and anger from the antiwar movement than soldiers coming home from World War II. Many had the additional burden of having received the novel diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), formerly referred to as “shell shock.” Despite having a diagnosis validated by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, they were still stuck with a condition little understood by the public and unsuccessfully treated.

“Many, like me, wondered if the stress, trauma and adversity they had experienced had injured their brains and if their illness came about because of their brains,” Phan says. “I also wondered if their being given this diagnosis for a condition that couldn’t be seen or pointed to contributed to their isolation, shame and guilt.”

Other brain-based conditions, such as stroke, epilepsy, Alzheimer’s disease and brain tumors, held medical explanations and organs that could be pointed to as a source, but there were no clear connections between the brain and mental illness. Full of questions about their illness, their experiences and the state of their brains, Phan looked to his teachers and his textbooks. Finding no good answers, he examined his personal connection to Vietnam.

“It really hit home when I met vets who served in the same country that I was born in, and who had fought for a cause that my father and my grandfather fought for,” says Phan. “I decided then and there to focus my work on understanding the biology behind PTSD, how it develops and why some soldiers get it and others don’t.”

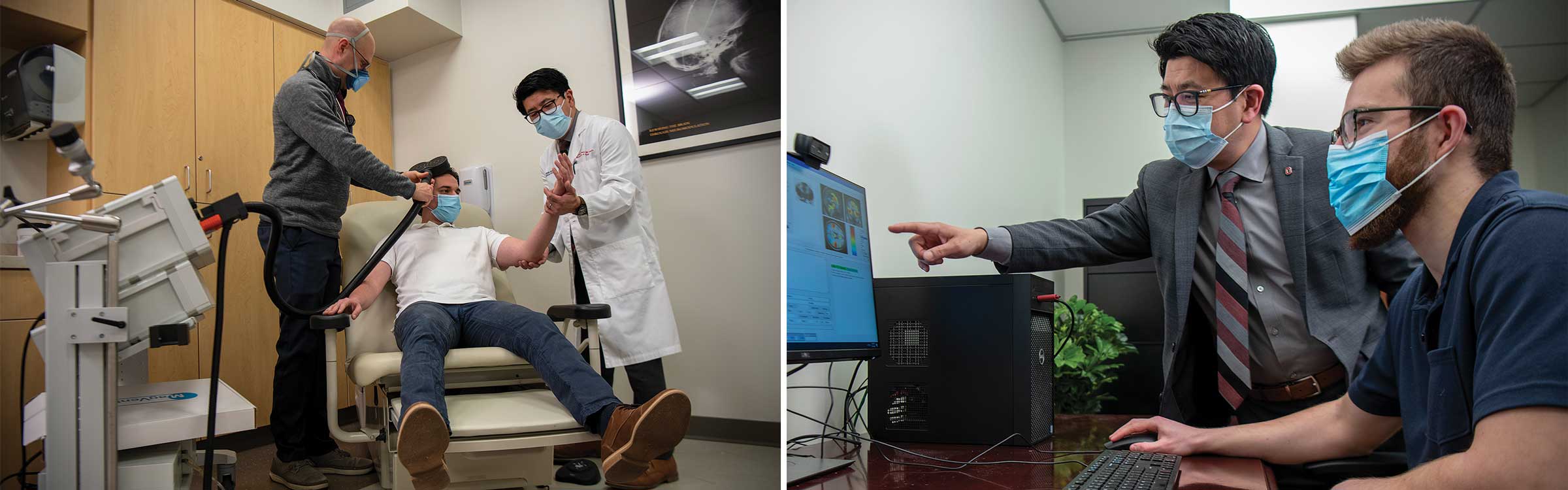

Dr. Phan uses advanced neuroimaging to study the impacts of stress, trauma and adversity on the brain.

A window into the brain

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) transformed psychiatric research by establishing that psychiatric disorders are, in fact, disorders of the brain and that diseases with similar clinical profiles can be differentiated on a neural (nervous system) level. Phan and his fellow researchers began using fMRI to examine and measure the electrical activity of brain cells, chemical activity and flow in the brain in real-time. fMRI provided a means to assay differences in properties and function in brain systems.

“We measured changes in neuronal blood flow and compared brain signal differences between patients with psychiatric disorders and normal subjects when performing different kinds of tasks and viewing various stimuli,” Phan says. “This elucidated how a brain in a state of disorder functions differently from a normal one.”

The differences in certain biochemical, neurochemicals and biomarkers in brains that had experienced high levels of stress, combat, trauma, chemical imbalance, and brain circuit dysregulation and dysfunction were stark. This illuminated how negative and traumatic life experiences could imbed in the brain and its biology, resulting in physiological imprints on brains that experience them.

“Trauma physically alters the topography of the brain while increasing cortisol and norepinephrine (a chemical in the brain that acts as a stress hormone) responses to subsequent stressors,” Phan says. “These changes can form the foundation for the development of mental illness.”

“Trauma physically alters the topography of the brain while increasing cortisol and norepinephrine (a chemical in the brain that acts as a stress hormone) responses to subsequent stressors,” Phan says. “These changes can form the foundation for the development of mental illness.”

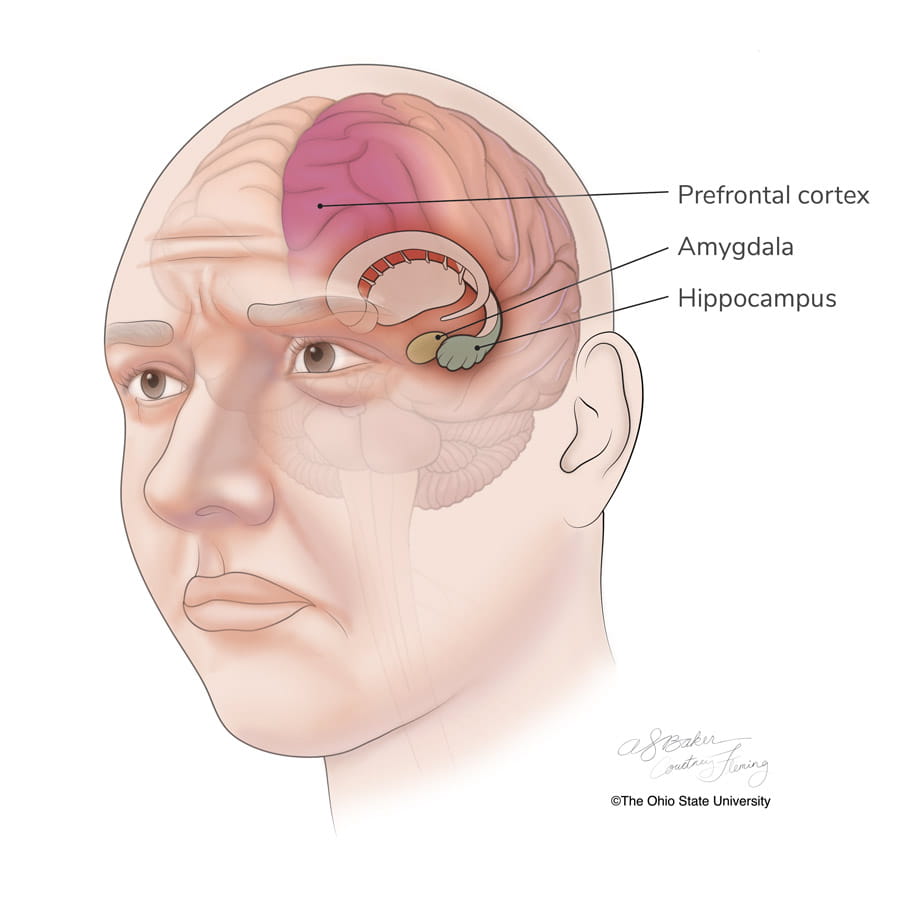

The amygdala, hippocampus and prefrontal cortex are areas in the brain that are implicated in the stress response. Phan says high activity in the amygdala shows increased activity in brain scans. Increased and sustained reactivity in the amygdala is characteristic of depression and other mental health diagnosis.

“We can measure and differentiate this activity in the brain much like how cardiologists measure heart function and heart attack risk through blood pressure,” Phan says.

Then they can prescribe medication, for instance, ones proven to reduce high activity in the amygdala, along with therapy and other interventions, much like how doctors provide medication to lower blood pressure.

K. Luan Phan, MD explains how his team is using brain imaging to reveal the impacts of stress, trauma and anxiety on the brain, and how this imaging can be used to identify and destigmatize mental health diagnosis.

“Showing patients and practitioners the differences between a brain that is able to bounce back from adversity and stress and one that isn’t, establishes a biological source,” says Phan. “Advances in neuroimaging allow us to show a patient why they feel the way they do and how changes in their brain contribute to symptoms and behaviors.”

This assigns responsibility to the organ responsible for mental illness — the brain — and can go a long way in helping ease the burden of self-blame patients often feel for their mental illness.

“If a patient has heart disease or cancer, we don’t blame them for the choices they made that led to their illness,” says Phan. “So this is liberating to patients, it reduces stigma and I think it makes them feel better.”

Bringing brain-based treatment to Ohio State

Phan was already an established international leader in the neuroscience of emotion, anxiety and traumatic stress before he joined The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in 2020, where he holds the Charles F. Sinsabaugh Chair in Psychiatry. Over the past 15 years, his brain-based research has consistently been funded by top agencies, including the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

He came to Ohio State from the University of Illinois at Chicago to build a psychiatry and behavioral health program that bases treatment and intervention for different illnesses and patient populations based on brain function and conducts research through the lens of resilience.

Phan says nearly half of the patients who undergo standard treatments for anxiety disorders, depression and PTSD do not respond adequately. In their research program, they balance the study of patients who do not respond favorably to interventions with the study of the other half who do. This helps them better understand how they can use the brain to explain this variability in treatment response and guide patients toward treatments that work.

“This is the promise of personalized medicine,” Phan says. “The power of brain imaging will help bring personalized solutions to the field of psychiatry.”

What works, what doesn’t and for whom

The aim to get those in acute mental health crisis into effective treatment comes at a crucial time. Despite an increase in mental health awareness and treatment, the suicide rate in the United States continues to rise, especially in vulnerable populations such as veterans.

Phan says while we may have greater appreciation and respect for what soldiers go through than we did in the days following Vietnam, interventions that target the biological basis of behaviors that lead to suicide are the way forward. His determination to address suicide in veterans led him to recruit to Ohio State one of the nation’s most innovative suicide prevention researchers, Craig Bryan, PsyD.

Dr. Bryan serves as professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health at The Ohio State College of Medicine and principal investigator of Suicide and Trauma Reduction Initiative for Veterans (STRIVE), which is now one of the leading research sites for clinical trials on suicide treatment, prevention and intervention. STRIVE provides leading-edge psychological treatment for military personnel, veterans and family members struggling with PTSD and suicidal thoughts. There has been a 75% reduction in suicide attempts among military personnel who received STRIVE treatments.

Read about Dr. Bryan's 'Zero Suicide' work for military veterans

“Knowing what interventions and treatments work for a patient with a certain personality type, experience, coping mechanisms, neuro-transmitter levels and biological variables, takes a lot of guesswork out of the equation,” says Phan.

Phan and his team also study brains that have recovered from difficult experiences, trauma and crisis, to measure how factors like social support, personal and family connections, spiritual faith, the capacity to regulate emotions and optimism contribute to resilience, the ability to bounce back despite adversity. Only 10-20% of people develop PTSD after severe trauma.

Phan reflects on a mantra from South African human rights activist Archbishop Desmond Tutu, which guides his dedication to a research-based approach to measure and build resilience in the brain.

“There comes a point where we need to stop just pulling people out of the river. We need to go upstream and find out why they are falling in,” Archbishop Desmond Tutu says.

“Our biological approach to aggressively treat brain-based symptoms and disorders relies on imaging, lab tests and research to determine treatment and effective intervention,” Phan says. “This builds support upstream from a mental health crisis or a suicide attempt and it saves lives.”

Compassionate mental health care

Explore the mental health services and programs offered at Ohio State.

Learn more

Support the future of mental health care

Your gift helps fund Dr. Phan’s research and other groundbreaking work evolving our understanding and treatment of mental health.

Give today