Bringing relief to people with headaches and concussions

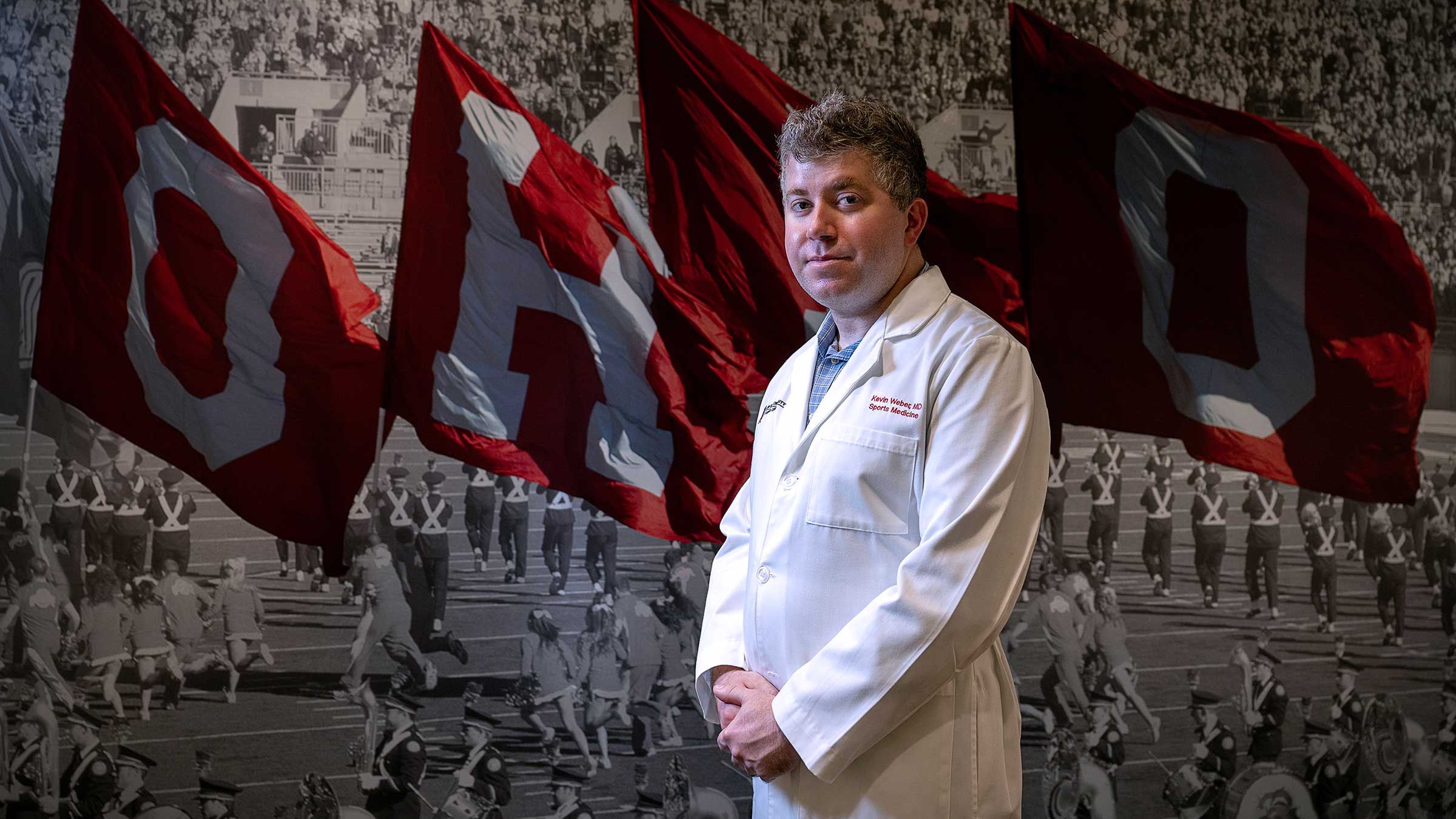

Kevin Weber, MD, MHA, has built an expertise in treating the migraine attacks he’s dealt with most of his life.

Kevin Weber, MD, MHA, wants his patients with chronic headaches to know he gets how they feel.

For his own headaches, mind over matter didn’t work. Starting when he was a teen, about once a month, he’d feel intense pain around his forehead and sometimes nausea. Light hurt his eyes.

Migraine attacks became more frequent when he was an attending neurology physician with a staff of resident doctors to guide and patients to treat. He’d listen to his patients describe their throbbing pain, at times while trying to ignore his own.

These days, Dr. Weber only gets a migraine attack every couple of months. The medication he takes allows him to spend most of his workdays helping his patients find similar relief.

Since he started the headache clinic at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in 2016, Dr. Weber has helped recruit and train more neurologists to treat an ever-expanding number of patients with headaches that over-the-counter medications can’t dull.

He also specializes in treating people with concussions: former NFL players and high school athletes, older people and many experiencing their first serious head injury. What he finds most fulfilling in his work is that with new guidelines on treating concussions and with the many new treatments for headaches, his patients, by and large, get better.

Solving the headache puzzle

Dr. Weber dims the overhead fluorescent lights before introducing himself to the morning’s first patient, a male ballet dancer. A month ago, the dancer’s head hit a wooden awning being hauled onto the stage. He still has dizziness, insomnia, daily headaches.

“Even something as simple as walking up the stairs gives me a headache,” he says.

After a series of questions, Dr. Weber asks him to stand up and close his eyes, then again, with his left foot directly in front of his right. The man wobbles a bit.

“That’s not surprising,” the doctor says.

A concussion can interfere with the communication between the brain and the nerve cells in the inner ear that offer a sense of balance, Dr. Weber explains.

He suggests physical therapy with a concussion therapist. He prescribes a steroid, melatonin for sleep, magnesium and light exercise. No weightlifting or running. No dancing for a while.

“You probably need to ease back into rehearsing,” he says.

As for next week’s ballet tour, Dr. Weber advises him not to go. The man agrees; he doesn’t want to risk feeling worse.

Before his workday ends, Dr. Weber will treat a variety of patients: a retired police officer with headaches, numb feet and insomnia after a fall months earlier, and a woman in her early 40s who hit the back of her head slipping on the wet floor of a movie theater bathroom.

From sports fanatic to concussion expert

In his first year of medical school, Dr. Weber remembers a 13-year-old middle school football player outside of Seattle was in the news after suffering catastrophic brain injury from hitting his head during a game.

About the same time, NFL players, too, were making headlines. That fall, former Philadelphia Eagles defensive back Andre Waters took his own life at the age of 44. An autopsy later revealed he had developed chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) from repeated blows to his head that brought on depression.

The swirl of news reports of athletes’ head injuries, along with Dr. Weber’s longtime passion for sports, fueled his interest in treating concussions. Since Dr. Weber began practicing, new research has driven changes in how concussions are treated and when players are allowed to return to their sport.

“We used to think it was a good idea to have players sit in a dark room for days and not exercise if they got a concussion. Now we know that doesn’t work.”Kevin Weber, MD, MHA

After resting for 24 to 48 hours, light exercise helps the brain recover, if the exercise doesn’t put the person at risk of another concussion, he says.

Much more is known now about the effect of repeated concussions, and how that can lead to CTE. Still being studied is how many concussions can cause long-term damage and why some people are more susceptible to them than others.

Treating headaches

Among Dr. Weber’s patients at the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center headache clinic, most are women under 40 with migraine headaches. From several hours to a couple of days, their pain can linger.

To cut the number and intensity of migraine attacks, neurologists at the headache clinic can offer a range of treatments, tapping into the many new medications and devices made available in the last 10 to 15 years as well as physical therapy and supplements.

Various devices worn on the forehead, neck or arm can send electrical or magnetic pulses to nerves to calm down the brain activity associated with migraines. Supplements including magnesium and melatonin can be taken in combination with other treatment options to fend off headaches.

In 2018, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first class of drugs to prevent migraine headaches: calcitonin gene-related peptide inhibitors. They block the pain pathway associated with migraine attacks.

Another drug believed to interrupt that same pain pathway is Botox, a medication used for several years to reduce wrinkles before it was approved to treat migraine headaches.

About three-quarters of Dr. Weber’s patients find their migraine attacks become less frequent with Botox — and people are often willing to try it, at times with skin-tightening in mind as well.

“Sometimes I have 23-year-old patients who are getting Botox for headaches, and they ask me, ‘Can you put some around here?’” gesturing under his eyes. “I tell them, ‘You don’t have any wrinkles.’”

Training others on headache treatments

Headache disorders are among the most common neurological conditions. And yet, there are a limited number of neurologists who specialize in treating headaches.

When Dr. Weber started Ohio State’s headache clinic, he was one of few neurologists in the state — and nationwide — with that specialty. That’s partly why the clinic attracts a wide swath that includes out‐of-state patients.

Today, Dr. Weber trains neurologists at Ohio State and others across the nation on a range of treatments.

“He’s incredibly knowledgeable on the guidelines for treating headaches and concussions and the rules on when players are allowed to return to play,” says Andrew Sas, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of Neurology at The Ohio State University College of Medicine.

“He’s probably not going to tell you about that,” Dr. Sas says. “He doesn’t care about the spotlight being on him.”

Dr. Weber’s down-to-earth nature may be why patients relate to him easily and trust his judgment, Dr. Sas says.

“Any medication he prescribes, he knows the clinical trial behind it, the pros and cons of taking it, as well as how it works compared to other treatments.”Andrew Sas, MD, PhD

On the sidelines

On Friday nights in the fall, Dr. Weber paces the sidelines of football fields as a physician for Columbus City Schools football teams, a volunteer job he squeezes into his tight schedule.

“It’s peace of mind for the parents,” he says. “They’re usually pretty happy if there’s a neurologist there.”

And Dr. Weber is happy to be there, watching for injuries and if the injured seem to be stumbling, confused, going to the wrong huddle.

In high school, Dr. Weber played basketball, and he’s always watched a lot of sports, especially the Detroit Lions. Anyone who knows Dr. Weber knows his passion for the team based close to his hometown of Toledo.

Some of Dr. Weber’s colleagues joke that his career treating concussions and his love of football, the sport with the highest concussion rate, seem like a contradiction.

But the way Dr. Weber sees it, he’s supporting a sport that comes with the risk of concussions but also all the benefits of playing on a team. Changes in rules and equipment in football have made the sport less dangerous, and health care professionals know much more now about how to treat concussions.

Still, Dr. Weber says it might be tough if his three-and-a-half-year-old twin boys, at some point, really want to play football or soccer. He’ll probably let them, he says. It’s better to play a sport than not. And he’ll be watching them closely from the sidelines.

Take charge of your migraine headaches

Our patient-centered headache team has access to the latest research and treatment options to address your pain.

Take charge today