Working at the tipping point of gene therapy for eye diseases

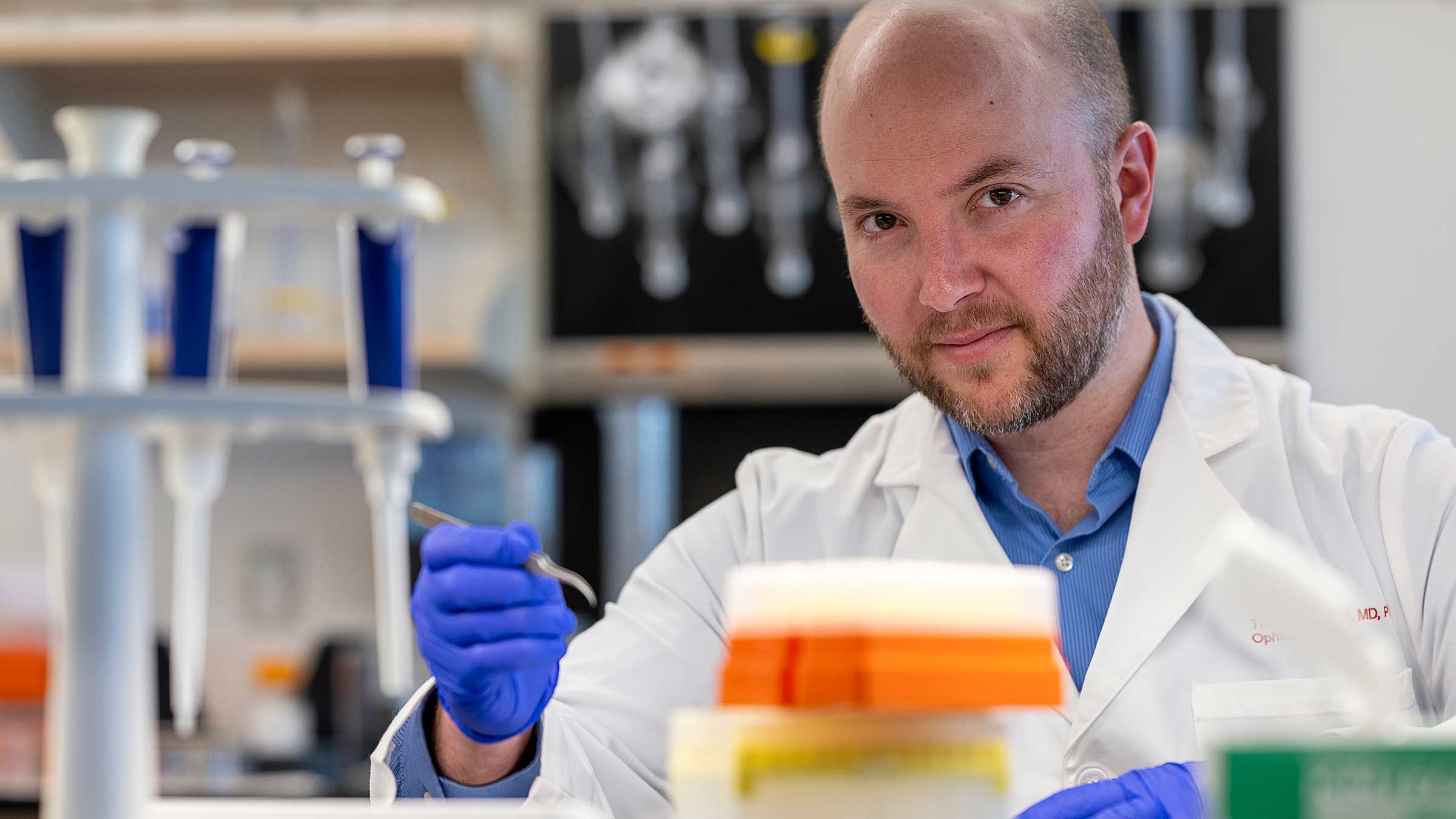

Thomas Mendel, MD, PhD, says treatments once believed out of reach are now just over the horizon.

Retina surgeon Thomas Mendel, MD, PhD, has been fascinated with scientific experimentation since the days when he was playing with action figures.

Many a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle was outfitted with his carefully constructed parachute designs, stuffed into a backpack and carted to a bridge near his boyhood home in Virginia.

He soon progressed to elementary and middle school science fairs.

But it was at Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology, which he describes as a “Hogwarts for nerds,” where the future ophthalmologist first became drawn to the science that led him to the study of light and optics.

Now, as founding member of The Ohio State University Gene Therapy Institute, Dr. Mendel is on the cusp of discovering gene therapies that could cure some of the most devastating childhood eye diseases.

Expanding success of gene therapy

Dr. Mendel, an assistant professor of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at The Ohio State University College of Medicine, specializes in treating conditions of the retina. He also seeks to find cures for inherited retinal diseases in his lab in the Pelotonia Research Center.

Working with patients with inherited retinal conditions is a challenge. There are hundreds of molecularly specific causes of inherited retinal disease, which account for vision impairment in 5.5 million adults. The retinal cells of patients deteriorate, causing night blindness, color blindness, light sensitivity and vision loss.

Patients are often told this loss of vision will continue to get worse and that there are no treatments.

But there’s hope that this will soon change.

Dr. Mendel has experience involving the first-ever FDA-approved gene therapy, Luxturna, which involves a one-time injection behind the retina of each eye. It treats a rare inherited eye disease called Leber congenital amaurosis, caused by mutations in the gene RPE65. Children born with the disease experience dysfunction of the retina with worsening vision over time and often become blind.

“The early success of Luxturna has dramatically changed the field and provided a glimmer of hope for patients with that specific disease,” Dr. Mendel says. “And what my lab is trying to do is to expand that success, since Luxturna can treat less than 1% of patients with inherited retinal disease.

“To do so, we need a new surgical approach that avoids the downsides of subretinal injection but still delivers gene therapy efficiently without inflammation.”

Rather than inject gene therapy behind the retina, where Luxturna is injected to target the pigment cells, Dr. Mendel’s approach applies the gene therapy in front of the retina by temporarily removing the vitreous gel — the substance that makes up about 80% of the eye — and filling the eye with air. In this way, he can focus the gene therapy directly on the retinal surface and prevent it from touching other parts of the eye, such as the lens or iris, which might lead to inflammation.

The addition of insulin to the mixture causes the cells within the eye to draw in the gene therapy very quickly, so it only touches the retina surface for 30 minutes.

This early work has garnered funding support from multiple foundations, including a five-year Career Development Award from the Foundation Fighting Blindness, and is being considered at the National Institutes of Health.

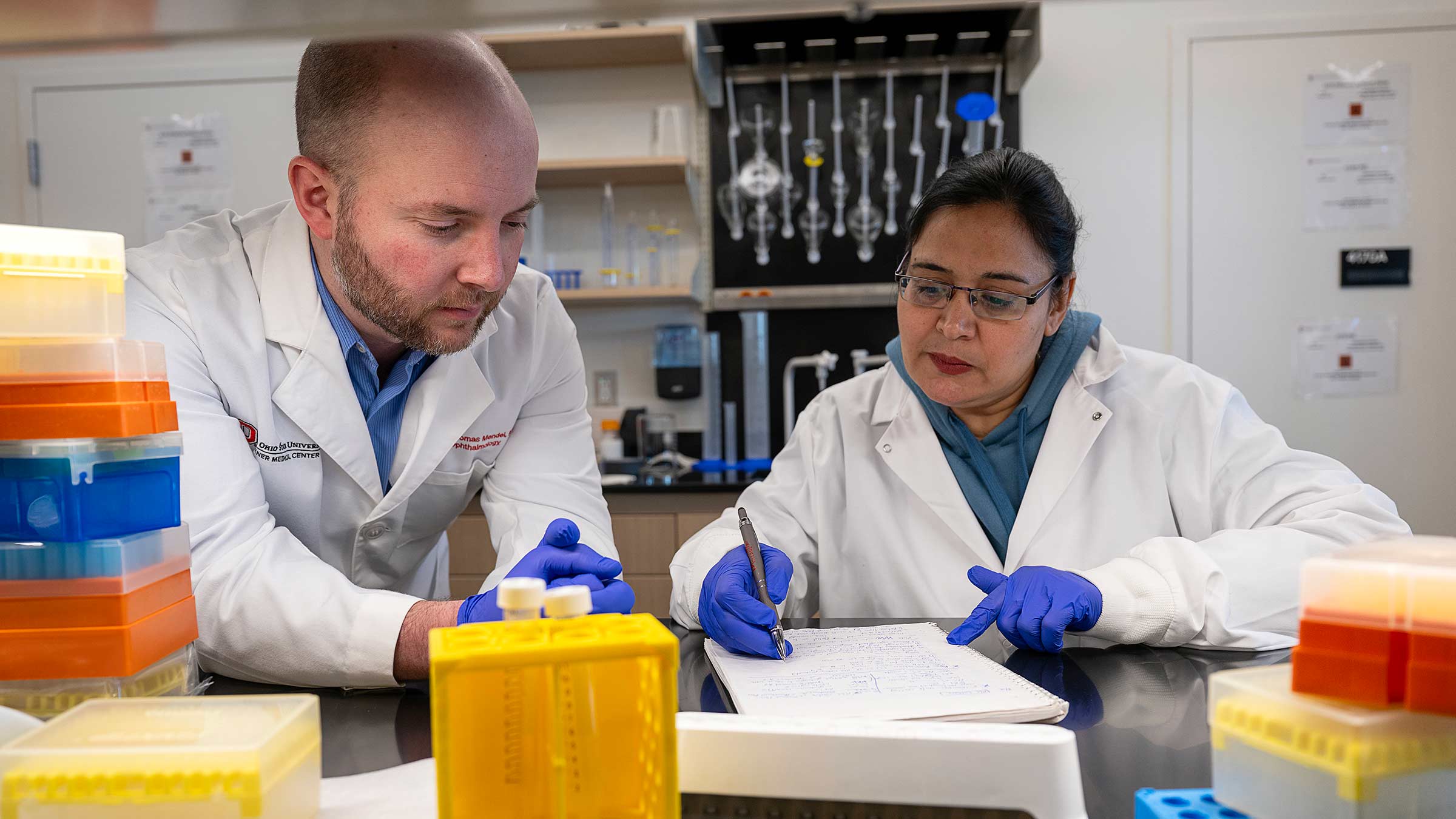

Sayoko Moroi, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at the Ohio State College of Medicine, says she’s grateful for the strong team approach between the department and the Gene Therapy Institute.

Along with Ohio State clinicians and partners at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, she says, this collaborative culture has provided a community of individuals, equipment and facilities in which Dr. Mendel has been able to focus on developing his lab program.

“This combination of outstanding people, state-of-the-art facilities, protected time for research and funding are the key ingredients for Dr. Mendel’s success and nationally growing reputation. I aim to see him contributing to first-in-human gene therapies and making a significant impact on reversing blindness from retinal diseases,” Dr. Moroi says.

Dr. Mendel says he expects to achieve initial success within three to five years. To do that, he’s expanded the number of research projects and the number of people who work in his lab.

The lab’s goals include making breakthroughs as quickly as possible and gaining support for the necessary grant funding to continue discoveries.

Exhausting all options for progressive eye disease

The robust approach is also apparent in the way Dr. Mendel cares for his patients.

The Havener Eye Institute at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center now includes a genetic counselor and a clinical trials specialist who work alongside physicians. They help explore any new treatment options and possible research trials available to patients.

“We make sure that our patients are absolutely up to date with the most recent research as of this week whenever they see us,” Dr. Mendel says.

Genetic counselor Taylor Sabato, MPH, MMSc, LGC, says Dr. Mendel has embraced this team approach, and each patient has a community of support to answer questions and leave no stone unturned.

If a patient is given a diagnosis that may be genetic in nature, Sabato will meet with the patient and run genetic testing if the patient is interested.

If a clinical trial with a potential treatment is available, the group works together to help patients explore the benefits and risks, coordinated and customized for each patient by Lindsey Pyers, COA, CCRP.

“Often, when someone learns that their eye condition may lead to progressive vision loss, they want to explore and exhaust all possibilities,” Sabato says. “That’s why they come to us. They’re looking for more and to be on the cutting edge of what we know about their disease and to learn more about what treatments are coming down the pipeline.”

She also says Dr. Mendel is a leader in his field who helps inspire his colleagues and staff.

“He is so passionate about saving vision and so motivated. On the really hard cases or the really hard days or the really long days, he just provides energy to the team. It’s infectious,” Sabato says.

T-ball games and daily rounds

Mendel grew up in Virginia, with a dad who’s a family doctor and a mom who’s a pediatric nurse. As a 6-year-old boy, he’d finish T-ball games then go on daily rounds with his father to check on patients.

A stint as a photography editor at his college newspaper at Duke University was an extension of the love of light and optics he’d gained in high school, and he became attracted to the challenge of microscopic surgery at the University of Virginia School of Medicine.

Then, the siren call of research came again as he worked in the lab of an eye surgeon after his third year of medical school. A stint planned for one year turned into five years of rewarding research and a PhD, resulting in publication and funding for a project in stem cell therapy for diabetic retinopathy, a retinal disease caused by high blood sugar from diabetes.

He chose an academic career so he could continue with research, and he now lives within walking distance from his Ohio State laboratory.

He has two young sons and a daughter, and he’s often back on the T-ball field between his own rounds, now serving as a coach.

Three-ring circus

Dr. Mendel describes his weekly schedule as a bit of a three-ring circus: He oversees the lab, he performs surgery and he works in both an adult clinic at Ohio State and a children’s clinic at Nationwide Children’s Hospital.

He says the decisions he faces can make the difference between sight and blindness, between new therapies that he’ll ultimately be able to bring to his patients and research that dies on the vine.

“I realized very quickly that I need to be very, very much reliant on good teams. And I have to surround myself with really good people. The reason I came to Ohio State is because I could see the resources to do just that were here. The support from Dr. Moroi and the opportunity to really make a dent in some tough diseases were here,” he says.

Sabato says knowing Dr. Mendel is putting in time at the lab serves as a pick-me-up for his team.

“His ability to go from the lab to the clinic and then back to the lab brings a really unique perspective,” Sabato says.

“When we have those tough clinical cases, he’s then able to take these real-world experiences and apply them in his lab. That has always been a really big motivator — that our team’s work continues even when we are not seeing patients in clinic,” Sabato says.

Dr. Mendel says the work is also self-motivating.

“As a surgeon, you want to fix things,” he says. “As a resident, it would be unsatisfying to go to these appointments. It really hurts deeply not to be able to offer treatment for patients slowly going blind. But, until recently, that was all anybody had for any inherited retinal disease.

“Now, I get to tell them honestly, ‘I’m working on your condition in my lab.’ In five or 10 years, I won’t have to tell parents that their child is just going to be blind.”

Ready to learn more about eye care?

Ohio State's ophthalmology team provides comprehensive care backed by one of the nation's leading academic health centers.

Expert care starts here