Stroke of luck: Ohio State neuroscience grad student fully recovers after massive stroke

Quick action by co-workers helped speed student to lifesaving care.

Stephen Vidman lay motionless on an operating table.

Even though he couldn’t move or speak, he was acutely aware of what was happening to his body.

Vidman, 28, had just suffered a massive stroke that paralyzed his right side. He couldn’t walk. He was unable to speak clearly.

“These stroke symptoms are progressing, and I know that each moment my neurons are deprived of oxygen, they become more damaged,” he says.

“I could feel my thought process becoming more slow.”

A stroke prevents oxygen from reaching the brain. Most strokes happen when blood vessels to the brain become blocked by a clot. About 25% of stroke patients die within a month of the initial stroke.

Those who survive often face months of rehabilitation and sometimes are left with permanent physical and mental deficits.

But unlike most stroke patients treated at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Vidman is also a first-year neuroscience graduate student who works to find new ways to help neurons sustain activity after spinal injuries and strokes.

Rather than dissecting that trauma and searching for solutions in a laboratory, he was now the one experiencing it.

There was a clot about the size of a pinkie tip that was blocking the blood flow to most of his brain.

Vidman knew the saying chanted for every stroke patient: “Time equals brain.” For every minute his brain went without oxygen, he knew a million neurons were lost. Those never come back. He hoped the injured ones would recover.

“That's one of my biggest fears, the idea that I could lose my cognition. I love science. I want to continue to do this,” he says.

An emergency exit from the laboratory

Vidman was at work at the Biomedical Research Tower on the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center campus on May 30. He was standing in the lab’s kitchenette talking on the phone with his mom when the first stroke symptoms began to appear.

“I couldn’t finish some of the sentences, and I couldn’t wrap up my conversation. It was weird,” he says.

Shortly after hanging up, he felt lightheaded. Then numbness set into his right arm and right leg. His limbs were losing function.

He managed to sit down.

Vidman will never know for sure what caused his stroke, but experts say injuries from an accident 10 years earlier may have induced it. He was working a summer job as traffic flagger for the Ohio Department of Transportation when a flat-bed tow truck struck him. He underwent major heart surgery, including a stent and a graft.

Initially, he thought the symptoms were due to the heart medication he’s on. Sometimes lightheadedness and numbness of his limbs are side effects.

“My function didn’t come back when I sat, so I stood up to try to see if I could walk it off. I fell over,” Vidman says.

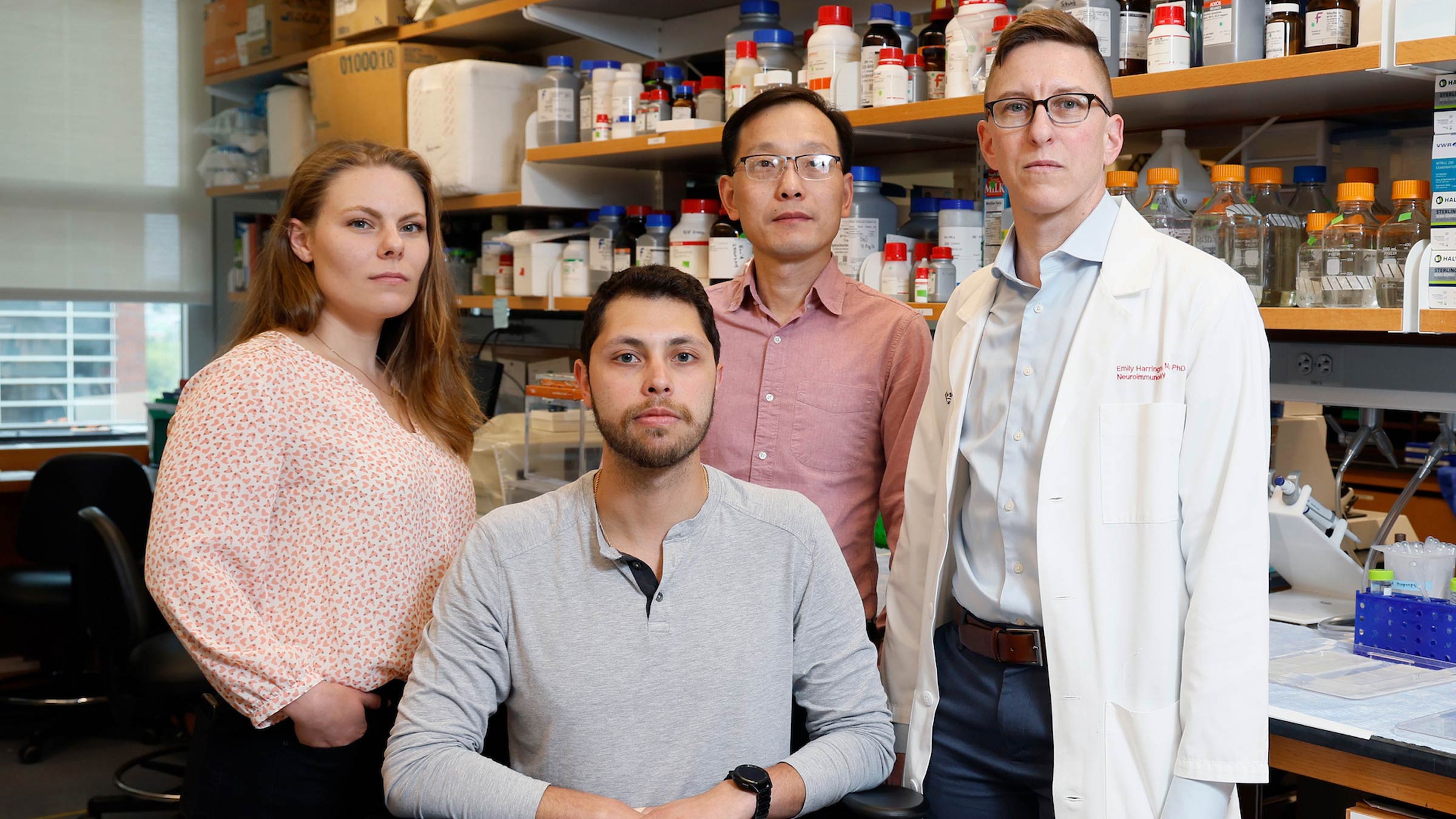

Hongjun (Harry) Fu, PhD, an assistant professor in the Department of Neuroscience, and Calli Bellinger, a second-year neuroscience student, walked over to him.

“I tried to get up. I’m like, ‘I’m fine,’ but I couldn’t speak,” Vidman says.

Bellinger raced down the hallway looking for help.

“It was very terrifying because I knew it had a high potential to be really bad because when you have neural damage and lose a neuron, it’s gone for good,” Bellinger says.

She found Em Harrington MD, PhD.

Dr. Harrington, an assistant professor of Neurology at The Ohio State University College of Medicine, quickly examined Vidman. Dr. Harrington knew he had suffered a stroke and gathered their colleagues to position Vidman in two rolling office chairs.

Bellinger called 911 to alert dispatch and EMS. Dr. Harrington called their fiancée, Jillian Maitland, MBA, BSN, RN, nursing director for Ohio State Emergency Services, to let her know what was happening and to prepare for their arrival.

“I often go visit her,” Dr. Harrington says. “You can walk to the back entrance where the ambulances arrive in less than 5 minutes. I was thinking, ‘How long is it going to take EMS? I know he's having a huge stroke and he needs to get there now.’”

Dr. Fu, Bellinger and Dr. Harrington began rolling Vidman in the office chairs outside of the building toward the Emergency Department.

They were met by Maitland and Stephen Aberegg, RN, CEN, near the EMS entrance, where they transferred Vidman to a gurney.

Maitland had a bed waiting, and a stroke alert was activated.

“Fortunately, our neurology team was already there because we already had one or two strokes actively being evaluated at that time,” Aberegg says.

Stroke team launches into action

Krystin Miller, MD, an Emergency Medicine physician and an assistant professor of Emergency Medicine at the Ohio State College of Medicine, was on duty that day. She sometimes sees several stroke alerts during her shift, as the medical center sees about 180 to 200 stroke patients per year, on average.

Stroke patients are administered an assessment that has a score ranging from zero to 42, with a higher number indicating more severity.

Vidman scored a 21, Dr. Miller says.

“So that was a pretty significant stroke with deficits,” she says.

Vidman was given a clot-busting medication and evaluated for a thrombectomy, a neurosurgical procedure to remove the clot, that has to be done within 24 hours of a stroke.

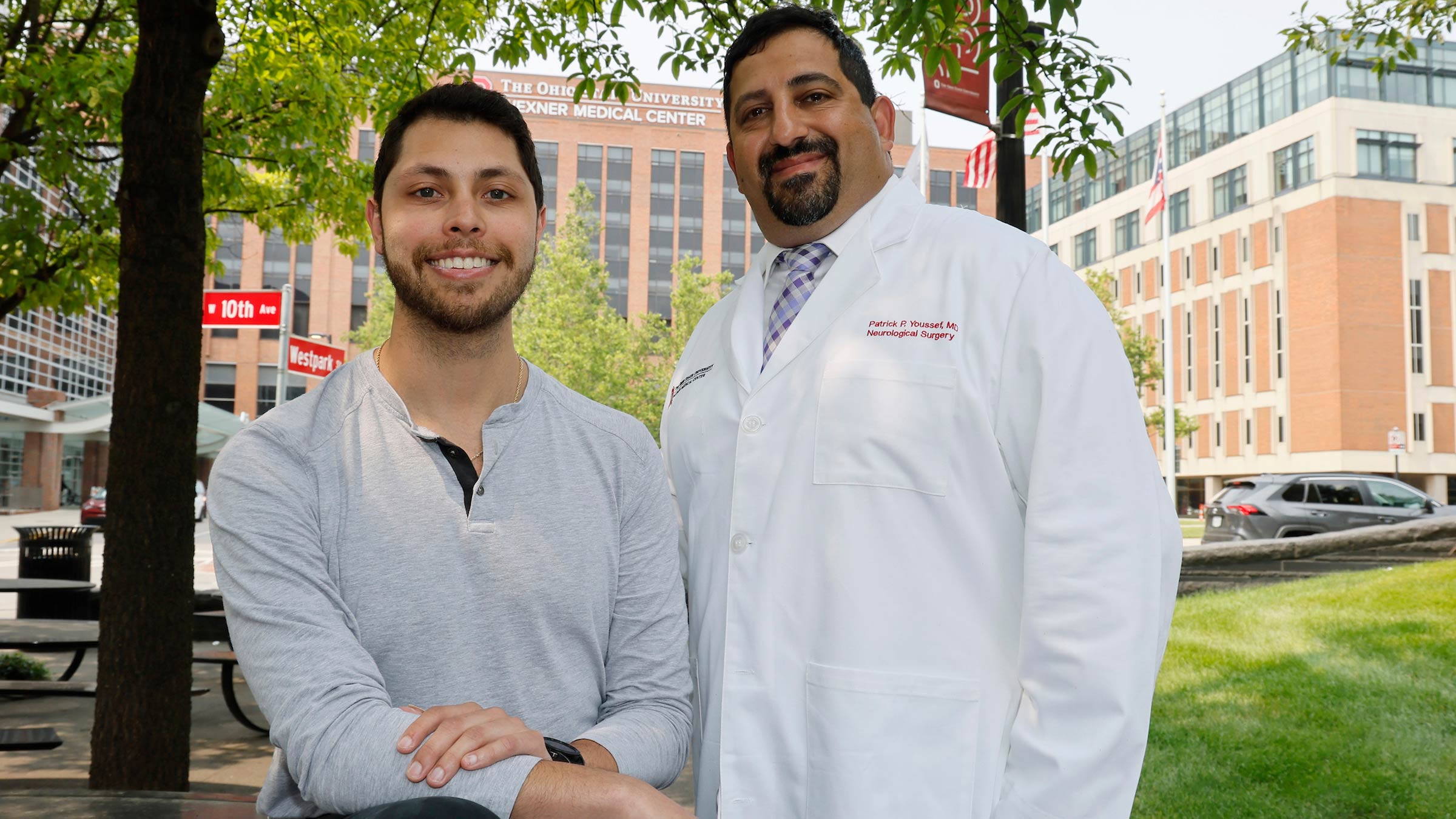

A thrombectomy can take as little as 15 minutes for healthy patients, but the results are life-altering, says Patrick Youssef, MD, a dual-trained vascular neurosurgeon and assistant professor of Neurological Surgery who performed Vidman’s thrombectomy.

Vidman’s procedure took place about 90 minutes from the time he had his stroke. He was awake for the procedure.

“You could see the fear in his eyes, and the only thing I could say is, ‘Hang tight. We’ll do the best we can to take care of you,’” Dr. Youssef says.

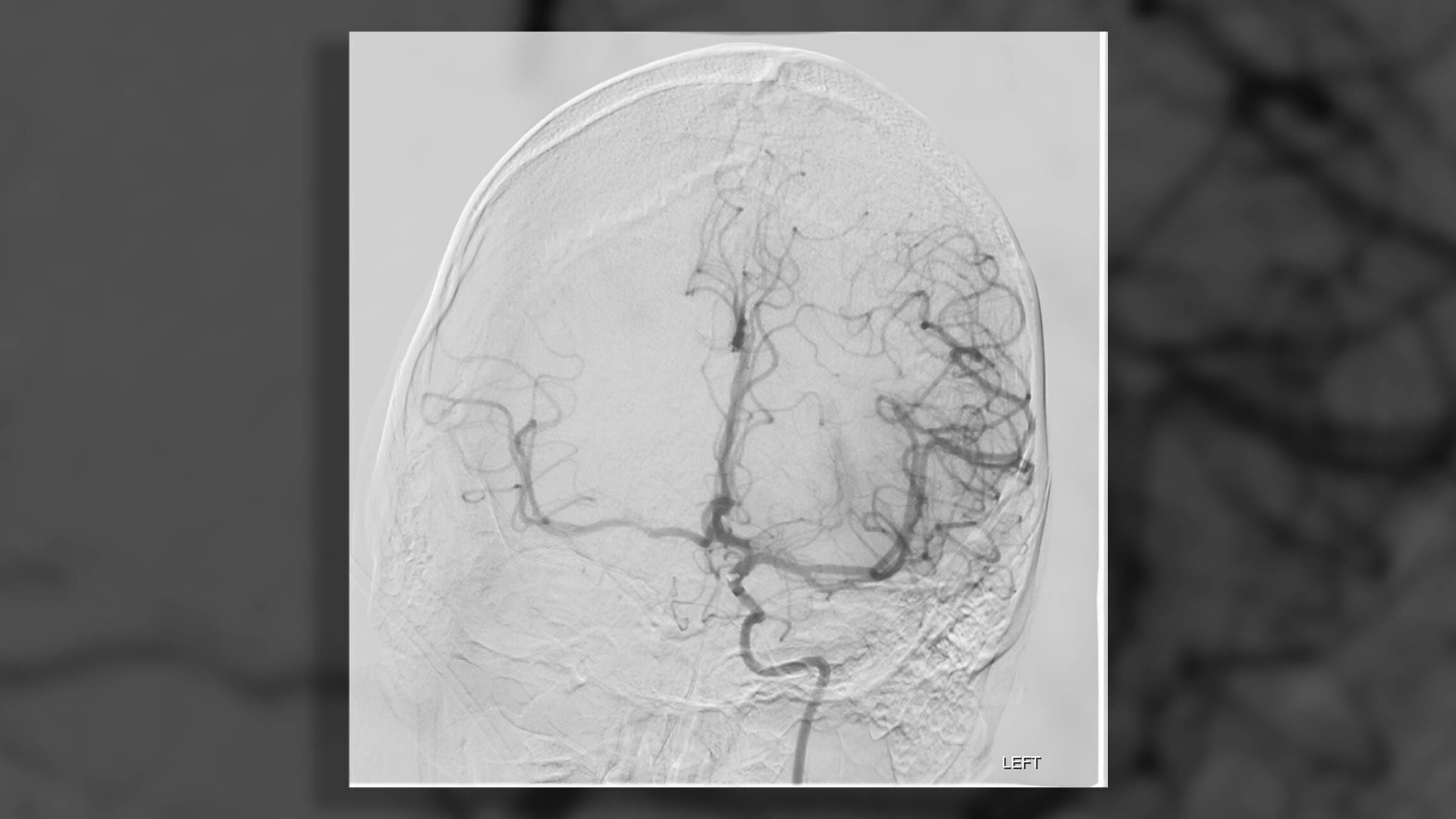

Scans showed that Vidman’s middle cerebral artery on his left side was blocked by a blood clot.

That part of the brain is usually responsible for speech and comprehension. The left side of the brain also supplies blood to the parts of the brain that control the movement and sensation on the right side of the body.

A miraculous recovery

Vidman’s clot, measuring one centimeter by half a centimeter, was successfully removed by suction.

“He just instantly started speaking better and moving his right side,” Dr. Youssef says. “It was really, really satisfying and heartwarming to see it happen. We don’t normally see it happen on the table.”

When the blood flow is reestablished, injured neurons will reactivate.

“You get those cases every once in a while, and when you do, it leaves a little lump in your throat and a little tear in your eye, because you see someone improving right in front of your eyes,” Dr. Youssef says.

Vidman recalls his function coming back.

“I looked at my hand and I was moving it, and I believe it was Dr. Youssef who showed me my blood clot that he pulled out,” Vidman says. “I was thinking, ‘Wow, that’s really interesting. But it’s really scary because that was blocking blood flow to more than half of my brain.’”

Vidman’s case was unique.

“We don't normally see strokes that young, but the real kicker is that it happened across the street,” Dr. Youssef says. “He’s one of the fortunate few that recovered all the way or almost all the way. Not many people do that.”

A new resolve to fight neurotrauma

Vidman thinks about how fortunate he is. If the stroke happened while he was on a recent camping trip in Kentucky, his outcome could have been much different.

Instead, it happened near neuroscience colleagues and at an academic medical center with a designated Comprehensive Stroke Center, designed to provide the most advanced, lifesaving care.

“We are with them from the moment they enter the hospital to the moment that they leave the hospital,” Dr. Youssef says. “It’s comforting for us, and it’s comforting for patients and their families, as well.”

Vidman’s research as a graduate student includes examining the response of blood vessels that re-perfuse an area of the brain that has been without oxygen after an injury. He looks at how those vessels help stunted neurons sustain their activity.

“There are no treatments for neurotrauma,” Vidman says. “Some of the things that we work on would be able to be administered to stroke patients like me. That really is a motivator when you think of it that way. It gives me another perspective.”

Every stroke is different, and where you go for care matters.

Ohio State’s Comprehensive Stroke Center is at the forefront of stroke care and our teams are developing and delivering the most advanced and innovative treatments.

Learn more