Squaring off against a clever killer: breast cancer that extends to the brain

A determined Ohio State researcher strives to improve outcomes for breast cancer patients with brain metastases.

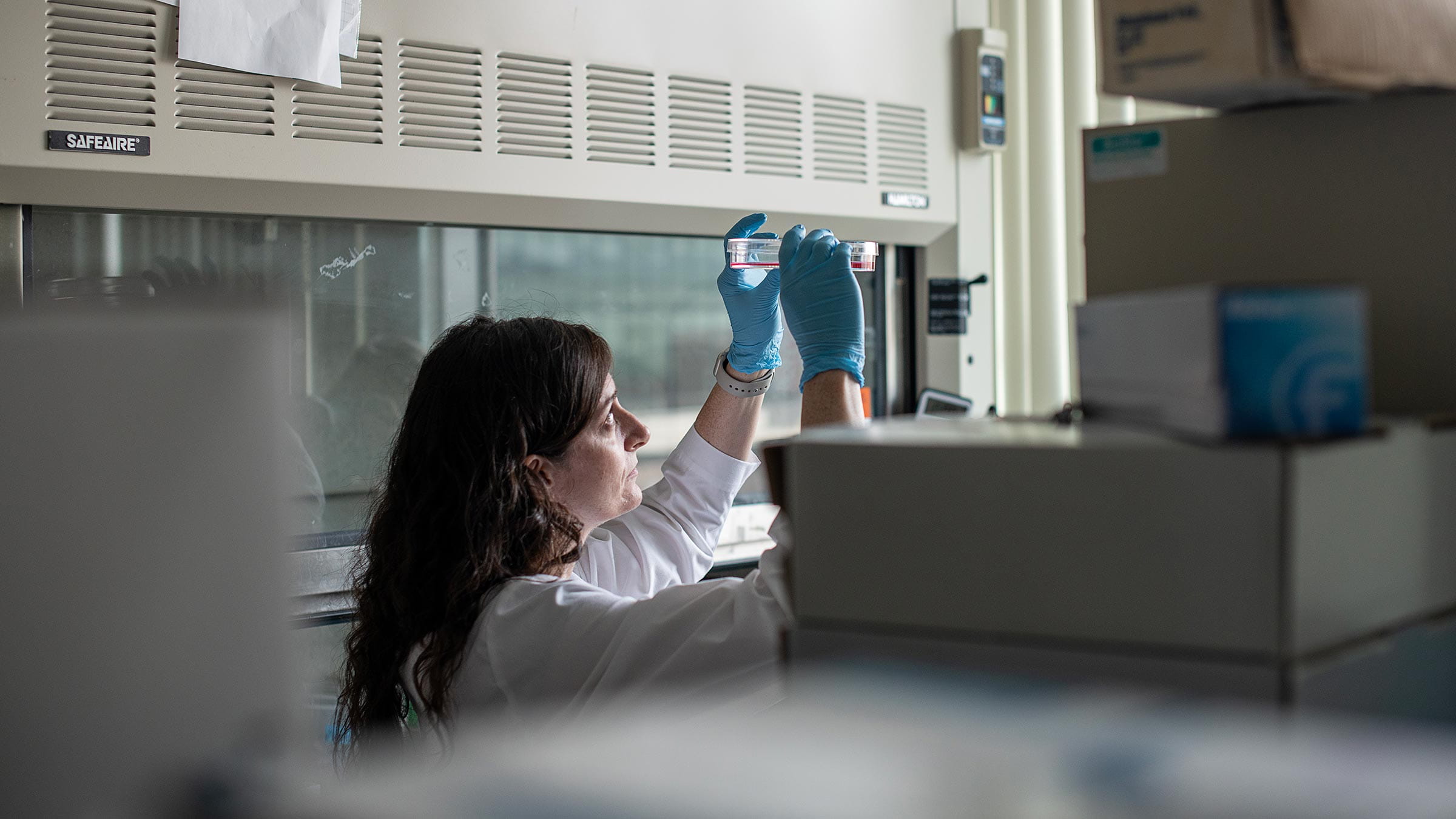

Cancer researcher Gina Sizemore, PhD, loves a good challenge.

And that’s a good thing, because she views her work to decipher the deceptive language of cancer cells as a challenge worthy of her best competitive efforts as a scientist and former high school athlete.

“Cancer cells are the ultimate magicians, adept at trickery,” says Dr. Sizemore, co-leader of the Cancer Biology Program at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute (OSUCCC – James).

As a researcher who focuses on how breast cancer cells grow and metastasize (spread) to the brain, Dr. Sizemore seeks to understand how these roving cells cleverly overcome the body’s natural safeguards and weasel their way into places they shouldn’t be. Because once they’re in, they’re very difficult to treat.

Studying how breast cancer cells ‘talk’

It starts with a single rogue cell that keeps dividing wrongly and with destructive force.

“The cancer cell itself becomes a tumor by creating a mass of cells that are growing out of control and not dying as they should,” Dr. Sizemore says. “But the cell that becomes cancer still has to interact with all the other cells in that organ. In the breast, that’s going to be things like fat, blood vessels, connective tissue and immune cells.

“I study how the cancer cell ‘talks’ to these other non-cancer cell populations in the breast,” Dr. Sizemore says.

“That interaction is important for the tumor to grow, and for the cells to then leave the breast and go to other sites in the body. We literally think about how the cells communicate with each other, as if a cancer cell is saying, ‘I want to leave,’ but the blood vessel replies, ‘No, you’re not leaving.’”

That, she says, is when the trickery starts, as the cancer cell releases signals to convince other cells that it’s OK for it to leave. When it gets into the bloodstream, it takes off toward other sites, including the brain.

Finding which breast tumor cells invade to create brain metastases

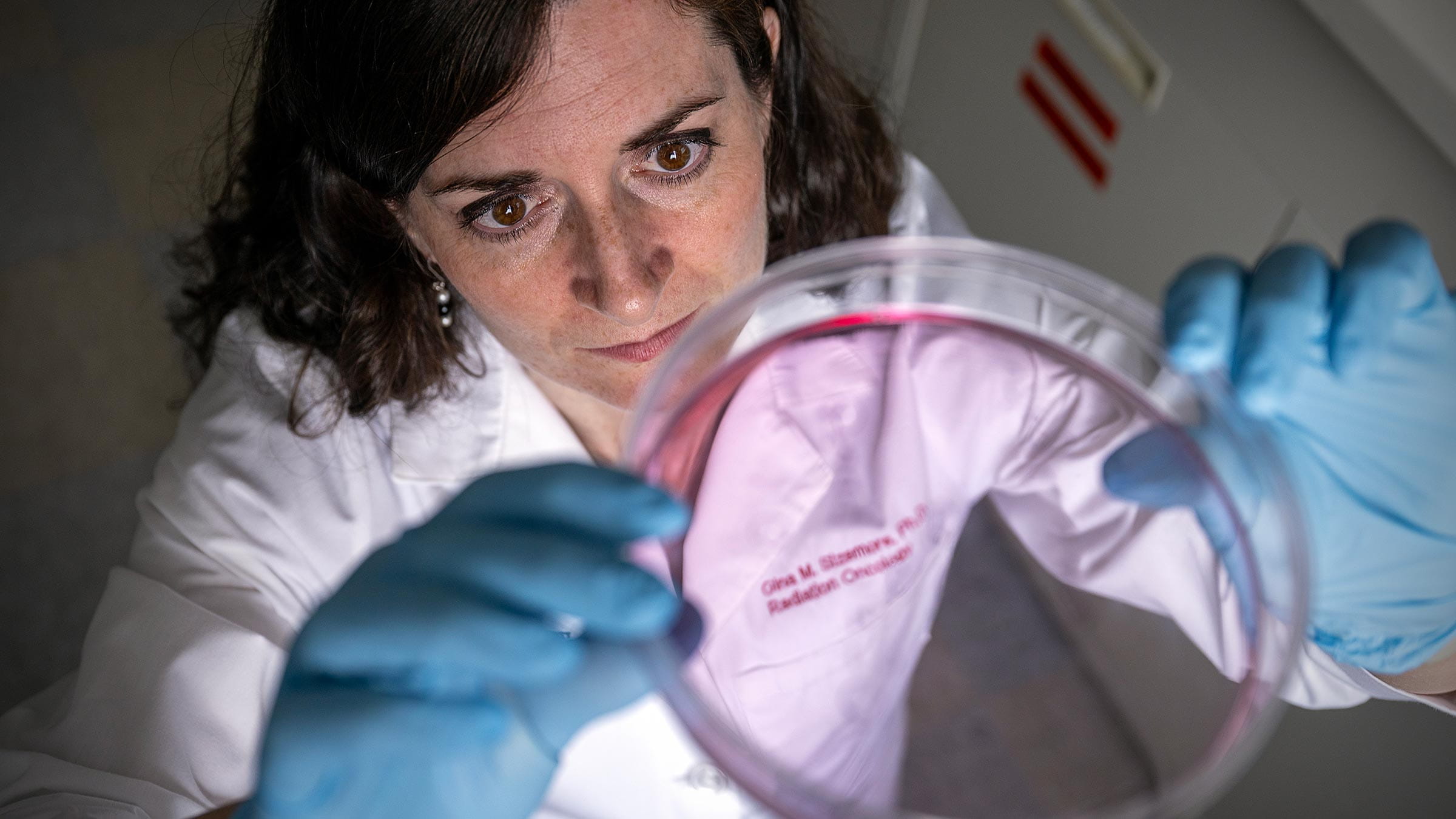

“My research is very much focused on the brain,” Dr. Sizemore says, explaining that when cancer cells arrive there, they again engage in conversation. “They want to enter, but the brain says, ‘No, you’re not allowed in.’ Then the cancer cells release signals, working to get inside and form a metastatic tumor.

“My team studies these cell populations and their interactions because we think we can find ways to predict which tumor cells will convince the brain that they’re allowed to live there. If we can do that, we can perhaps determine up front which patients diagnosed with breast cancer are at higher risk for metastasis and tailor their treatment differently.”

Dr. Sizemore is also interested in identifying drugs that can block certain cell-signaling interactions to either stop them from occurring or to better treat patients with established brain metastases (informally called “mets”).

“I decided to focus my career on brain mets, because in the breast cancer space that’s the most devastating scenario,” she says. “Other mets are also bad, but for patients with brain mets, the predicted survival is the lowest of all the other types. We don’t have good treatment options for those.”

Underscoring the urgency of her work are some dire statistics: Brain metastases arise in 10-20% of patients with metastatic breast cancer, and only 20% of those patients survive for a year after diagnosis.

“It’s just really awful,” Dr. Sizemore says. “We need to do better for these patients.”

Finding her way to breast cancer research

That’s a lofty pursuit for a person who had a shaky academic start.

Although Dr. Sizemore was always interested in biology, she devoted her high school days more to sports than scholastics. Besides playing softball and running on the track team, she was a four-year starter on the varsity basketball team and “kind of just floated through academically,” getting good grades but never feeling challenged by her school’s curriculum and thus “not really learning much. I was not an academic young person.”

She initially struggled as an undergraduate student studying biology and chemistry at Washington & Jefferson College, a school in southwestern Pennsylvania.

“I’d never learned how to study or what it meant to sit down and take a class, so at the beginning my advisors thought maybe I should try something different, but I told them I really wanted to do this,” recalls Dr. Sizemore, a Pittsburgh-area native who was the first person in her family to attend college. “With the faculty’s help and patience, I did a reset and ‘learned how to learn’ so I could compete with other students who already knew a lot about these subjects from their high school classes.”

As a college junior, she met a visiting Washington & Jefferson alumnus named Dennis Slamon, MD, PhD, a world-renowned breast cancer researcher who agreed to let her do a summer internship in his lab at UCLA. She acquired a Howard Hughes Medical Institute fellowship and headed west.

“It changed my life,” she says, “because I entered the world of breast cancer research. I decided that summer that I wouldn’t go to medical school as I had been planning. I wanted to learn more about biomedical research instead.”

After graduating, she returned to the Slamon Lab for two years. During that time, research from the Slamon Lab helped usher in Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of the drug Herceptin as a first-line treatment for breast cancers that are fueled by the HER2 protein.

“I can’t put into words how pivotal and crucial this experience was for me. It made me realize that I could perhaps also come up with new therapies that could help millions of patients,” Dr. Sizemore says.

She entered graduate school in 2005 at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, where she earned a PhD in pharmacology, the study of drug design and development.

On her first day of rotations at Case Western, she met her future husband, Steven, a student at Kent State University who was pursuing a PhD at the Cleveland Clinic. The two were recruited to Ohio State and married in 2013. Four years later, the Sizemores joined the Department of Radiation Oncology, where they are now associate professors. Both are in the Cancer Biology Program at the OSUCCC – James and have similar research interests. They also have two children, 9-year-old Gabriella and 4-year-old Juliana.

Success from the start

After only a few weeks at Ohio State, Dr. Sizemore received a grant from the OSUCCC – James Pelotonia Scholars Program that supported her research and led to a larger grant from the U.S. Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program. These studies laid the foundation she used to secure her first National Institutes of Health grant.

In 2018, she was the first recipient of the Block Lectureship Junior Faculty Award, which goes to promising scientists who are then mentored by that year’s recipient of the Herbert and Maxine Block Memorial Lectureship Award for Distinguished Achievement in Cancer. The 2018 recipient was Craig Thompson, MD, then-president and CEO of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Institute in New York. Dr. Sizemore worked with Thompson Lab postdoctoral student Simon Schwoerer, PhD, to publish an article in the journal Nature Metabolism on how fibroblasts in the tumor microenvironment (TME, or area around the tumor) help cancer cells survive.

Future directions in cancer research

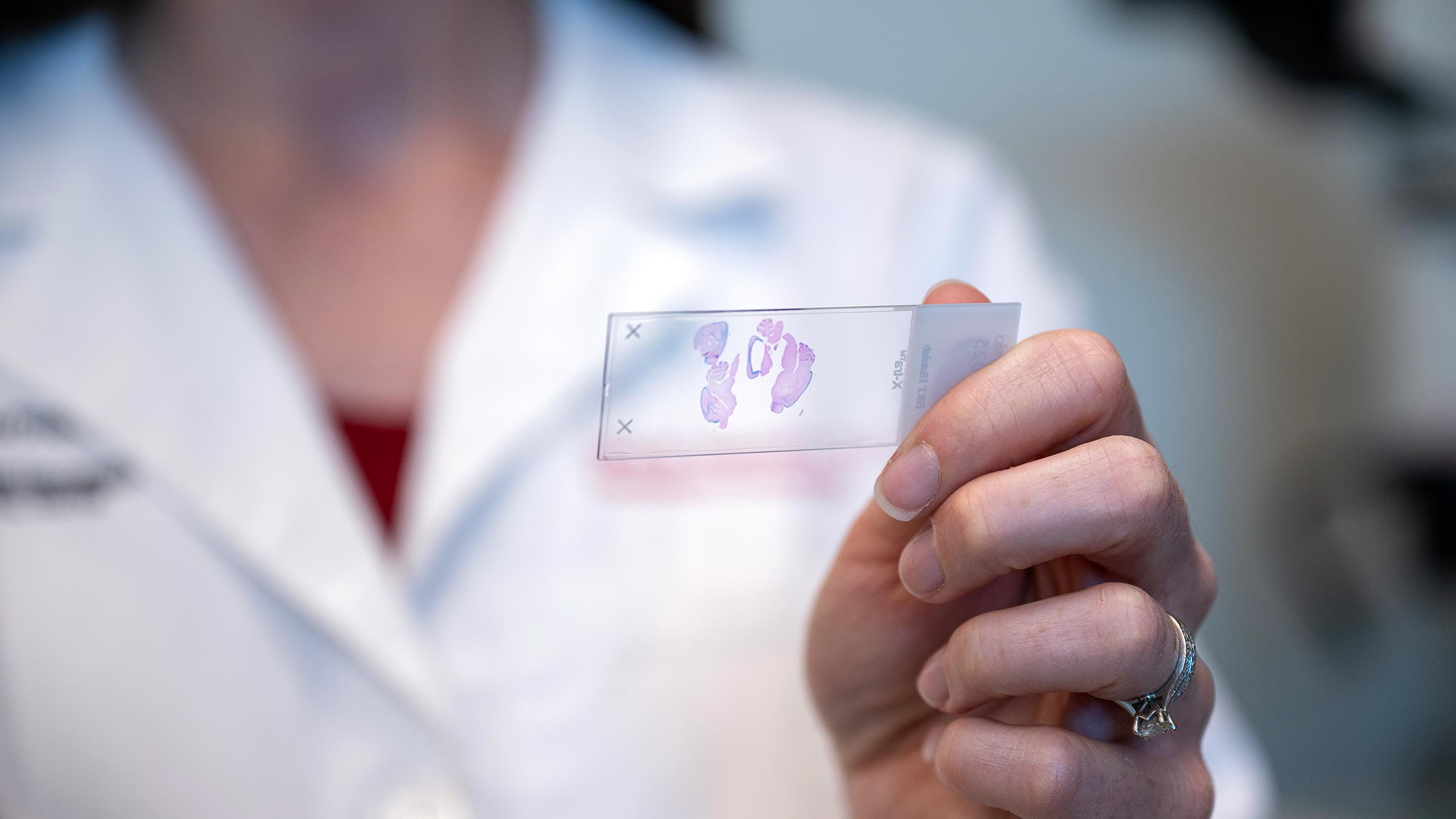

Dr. Sizemore’s lab team has since discovered a cell surface receptor called PDGFR-β that they believe functions in the start and growth of breast cancer-associated brain metastases. They’re creating mouse models that will help them better understand its function and perhaps identify diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for patients.

“In conjunction with my colleagues, we’re next going to move into human clinical trials to test whether we can use the PDGFR-β signaling pathway in people as a biomarker for predicting brain mets,” Dr. Sizemore says.

Dr. Sizemore also hopes to use samples of human brain metastases from patients undergoing surgery. “We can examine those samples for high levels of this pathway and see if we can make the cancer respond to targeted treatments,” she says.

To her, it’s all part of the academic challenge, toward which she applies a competitive drive that dates to her days as a high school athlete.

“I’ve always been someone who goes after challenges, and this is like, ‘Game on!’ … human versus cancer,” she says, adding that she is also propelled by the support of a generous community.

“We rely heavily on community efforts like Pelotonia to support our research, so I can’t face the community and not be able to say that I’m busting my butt in the lab. I love my work, and there’s just so much more to do.”

Your support fuels our vision to create a cancer-free world

Your support of cancer care and pioneering research at Ohio State can make a difference in the lives of today’s patients while supporting our work to improve treatment and reduce cases tomorrow.

Ways to Give