Standing on the shoulders of giants in leukemia research

Leukemia researcher expands mentors’ legacy to address health disparities

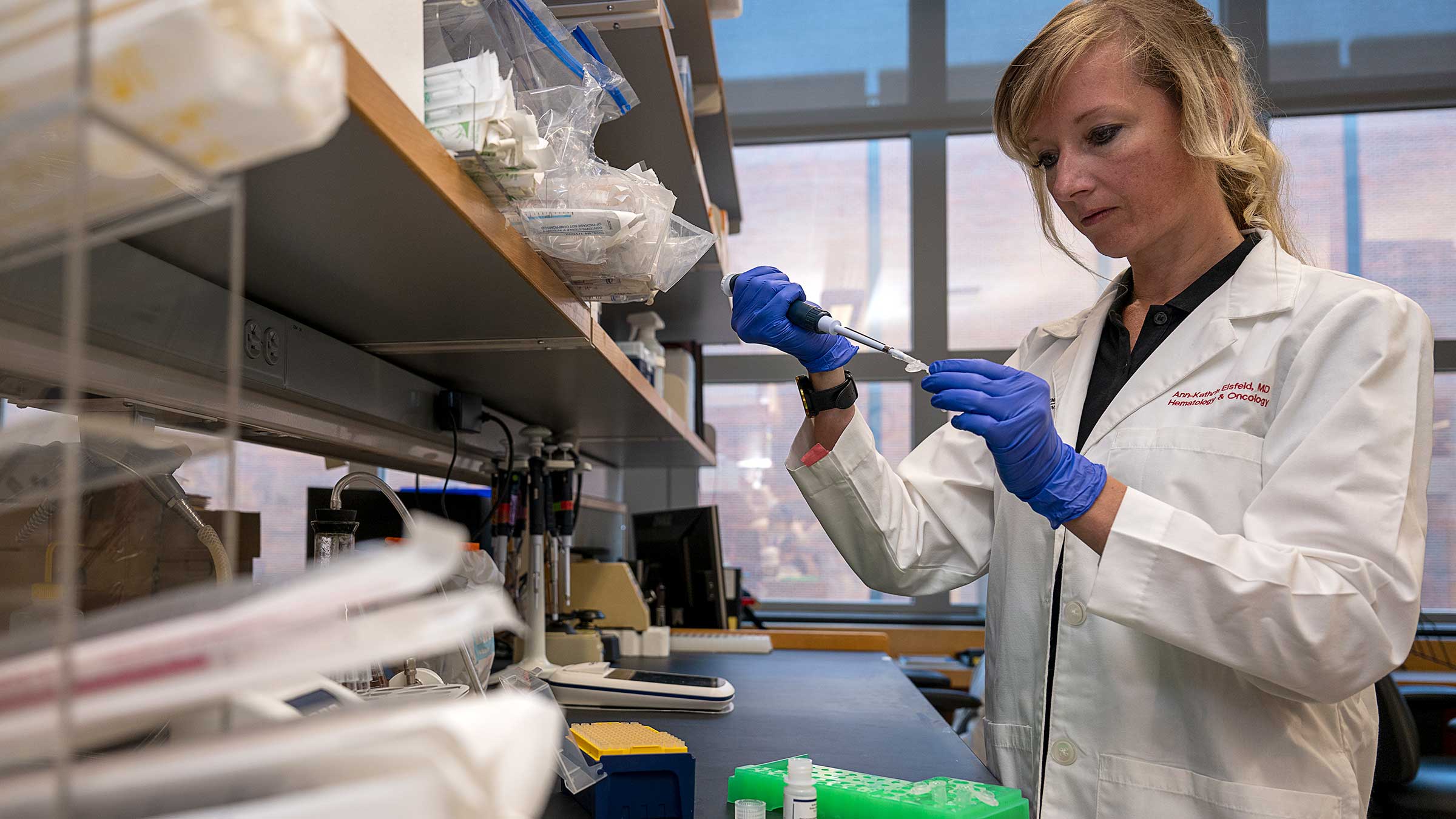

What brought Ann-Kathrin Eisfeld, MD, from her home country of Germany to become director of Ohio State’s Clara D. Bloomfield Center for Leukemia Outcomes Research was a series of unexpected events that, in hindsight, felt like fate.

Dr. Eisfeld wanted to work in hematology ever since a new bone marrow transplant center opened at the University of Leipzig medical school. After completing her residency and fellowship in hematology there, she was ready to become faculty and dive into leukemia research.

Instead, her boss suggested she start a family, which would be easier than the rigors of scientific research.

Dr. Eisfeld persisted.

At a hematology conference, she auspiciously met renowned leukemia scientist Clara Bloomfield, MD. She’ll never forget how Dr. Bloomfield responded when she shared that boss’s recommendation: “Hell! Come do a BTA — been to America — with me for two years, and nobody will ever tell you again you’re not ready for research!”

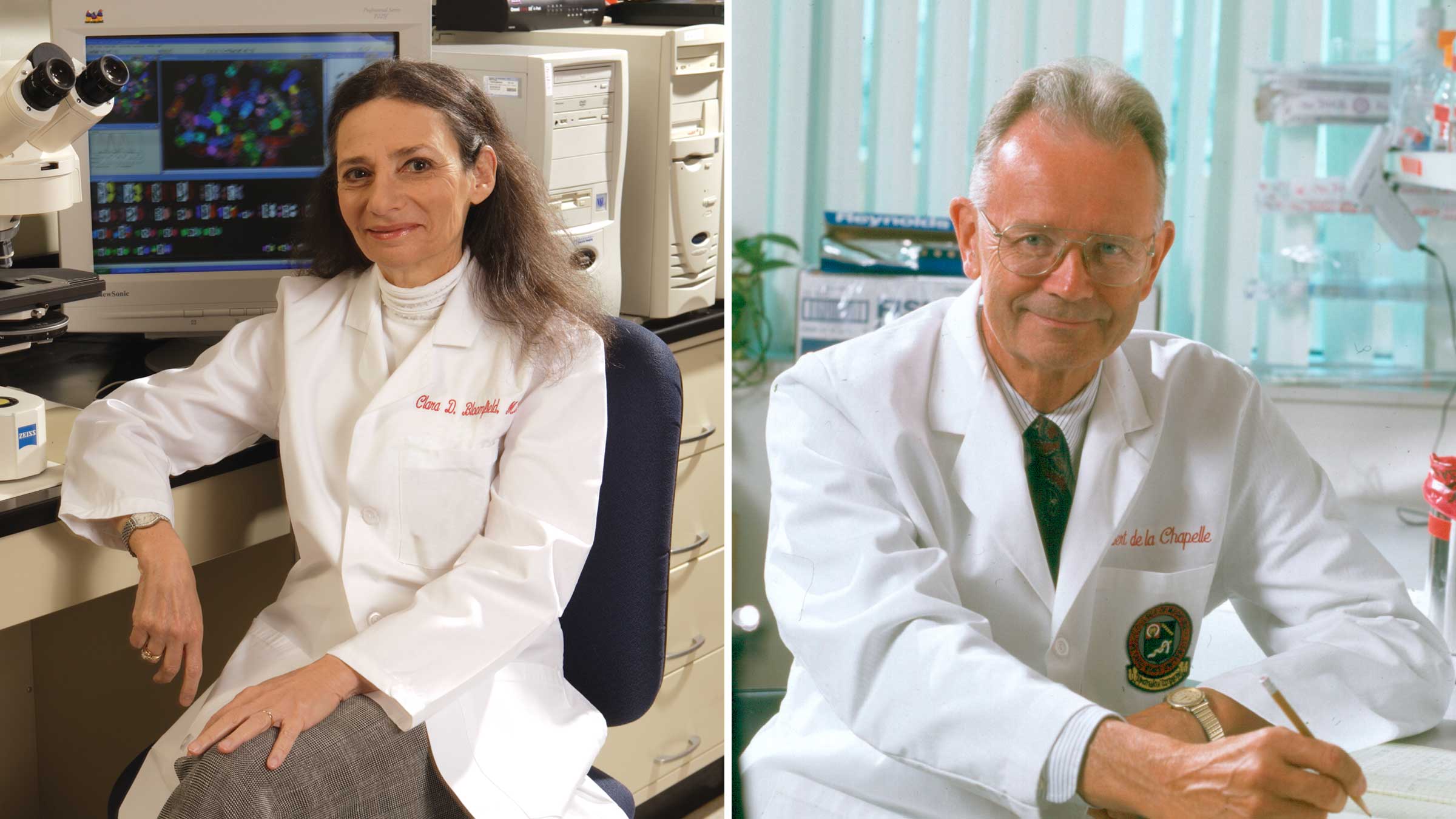

Dr. Bloomfield was one of the first female cancer center leaders in the United States and was instrumental in building The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute (OSUCCC – James) as a renowned cancer research institution. Her more than 50 years of groundbreaking research in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) revolutionized science-based, personalized treatment.

Dr. Eisfeld agreed to come to Ohio State to work in Dr. Bloomfield’s lab as well as the lab of her husband, renowned cancer geneticist Albert de la Chapelle, MD, PhD. Dr. de la Chapelle’s research led to seminal discoveries about cancer’s molecular and genetic nature, setting the stage for developing innovative treatments.

The pair usually didn’t share research fellows, but Dr. Eisfeld benefited from the best of both worlds. “I was in Albert’s lab doing genetic training and then worked with Clara on prognostics projects,” she says.

A two-year stint in research becomes a career trajectory

Dr. Eisfeld, who is today an assistant professor of Internal Medicine at The Ohio State University College of Medicine in the Division of Hematology, planned to do research at Ohio State for a few years. It wasn’t long before she was offered a position in the department of cancer genetics.

Dr. Bloomfield and another mentor, John Byrd, MD, then Ohio State director of hematology, advised her not to take it.

Dr. Eisfeld recalls her mentor saying, “In the end, you’ll regret it because what makes you such a good scientist is that you can connect it to patients. There are thousands of brilliant PhDs out there, but there are very few physician-scientists, and those are the ones who can make the most impact. Don’t underestimate the power of that.”

Dr. Eisfeld turned down the offer. That same week, she registered to take the medical licensing exam and repeat her medical training in the United States.

At the same time, Dr. Eisfeld was already knee-deep in data. Dr. Bloomfield and Dr. Byrd allowed her to lead one of the largest sequencing efforts ever in acute leukemia, using samples of 1,600 patients. With this data, Dr. Eisfeld and others have been able to conduct scientific studies that improve AML patients’ disease prognosis and treatment options based on genomic factors.

Becoming the leader of Ohio State’s leukemia research

Dr. Eisfeld wanted to devote her research to understanding each patient’s leukemia and why some respond to treatment and others don’t. Because this was the same area of expertise as Dr. Bloomfield, she figured she would need to move to a different research institution.

But then Dr. Bloomfield died unexpectedly in 2020. “It was clear that I could not leave. I could not leave Albert, and I had to continue Clara’s work,” Dr. Eisfeld says.

Ohio State opened a new center dedicated to Dr. Bloomfield’s research and legacy. On her first day as faculty, Dr. Eisfeld was named co-director with Dr. Byrd of the Clara D. Bloomfield Center for Leukemia Outcomes Research. “Even though I was just coming in as faculty, Albert and John supported having me be part of it,” Dr. Eisfeld says.

A few months later, Dr. Byrd moved to another research institution, and Dr. Eisfeld took over the helm.

“I was standing on the shoulders of a giant, and I could give back in some way to my mentor. My goal still today is to make Clara proud and continue her legacy,” Dr. Eisfeld says.

With every project, Dr. Eisfeld considers what Dr. Bloomfield would say. “If I want to look at something, I think about how she would ask, ‘Will this change clinical practice?’ or ‘Will this change the classification of AML?’ If the answer is yes, I will move forward.”

Expanding leukemia research to address health disparities

Dr. Eisfeld’s team, consisting of outcome research statisticians, data managers and a world-class cytogeneticist as well as her lab team, now support more than 50 active projects on AML worldwide. Dr. Eisfeld strongly believes in team science and data sharing, based on the highest standards of data quality. She’s been instrumental in building a research consortium across major cancer centers, which she says is key to collaborations.

For the continuation and expansion of major sequencing efforts to better understand leukemia, she closely collaborates with Elaine Mardis, PhD, co-director of the Institute for Genomic Medicine at Nationwide Children’s Hospital. “Elaine is one of the most influential cancer researchers and a wonderful person — it was such incredible luck that Albert and Clara introduced me to her.”

Today, Dr. Eisfeld’s lab has expanded the research to focus on how race, ethnicity and gender affect leukemia treatment.

She and her team have shown that race, sex and socio-economic factors all impact leukemia cell mutations, as well as treatment outcomes. Young Black patients diagnosed with AML have significantly shorter survival than white patients. “We’ve been the first to show there are survival disparities of African Americans, and that sex and social demographics affect survival outcomes and even possibly the occurrence of type and frequencies of biological mutations,” Dr. Eisfeld says.

Andrew Stiff, MD, PhD, a fellow in Ohio State’s physician-scientist training program, works with Dr. Eisfeld to sequence cancer cells in bone marrow samples. This data is compared to a vast data set, but most of the data is from people who are white, with Central European ancestry. The project is an enormous, collaborative effort between multiple institutions, with continued support from the Alliance of Clinical Trials in Oncology.

Research in Dr. Eisfeld’s lab has shown that different mutations in people from other places can cause cancer to mutate differently.

From his work with Dr. Eisfeld, Dr. Stiff has learned to consider where any diagnostic tools come from and whether it applies to the patient in front of him.

“If our knowledge is based on one segment of the population, we’re missing out on a lot,” Dr. Stiff says.

Dr. Eisfeld has thought a lot about how disparity questions that drive her research today aren’t the broad-sweeping ones Dr. Bloomfield once asked. Still, she thinks she could have convinced her mentor of their importance.

Before Dr. de la Chapelle’s death, nine months after his wife, he saw Dr. Eisfeld’s first plenary presentation on the lab’s disparities research results. “He said, ‘Clara would be very proud of that,’” Dr. Eisfeld says.

Personal experience guides shifting role from mentee to mentor

Drs. Bloomfield and de la Chapelle taught Dr. Eisfeld that answering a research question is more important than having first authorship on research results. “They were very generous, and they gave opportunities to others early rather than later,” she says.

Dr. Eisfeld paid that kindness forward when asked to give a keynote address at the German, Austrian and Swiss Societies for Hematology and Medical Oncology in Berlin.

Instead of taking the stage, she prepped and sent her 19-year-old research assistant, Isaiah Boateng. Boateng, who is Black, felt passionate about the questions being asked in the research with Dr. Eisfeld on the disparities between Black and white cancer patients.

“She made me rehearse that presentation like my life depended on it. She got that from Clara Bloomfield, who allowed her to grow,” he says.

Moving from bench to bedside gives more meaning to both roles

Dr. Eisfeld spends most of her time working in the lab, but her six annual weeks of in-patient rounds inspire her research. “It feels like a reality check. Nothing makes me happier than thinking this is someone I might have helped or knowing I should give a patient one drug over another because of something we found out,” she says.

Alice Mims, MD, a friend and colleague of Dr. Eisfeld, says patients in her clinic remember and ask about Dr. Eisfeld for months after an in-patient stay. “When my patients get their initial diagnosis from Dr. Eisfeld, they come to me already understanding the disease well and why we’re picking certain treatment options. They feel like she has their best interest at heart.”

In the end, Dr. Eisfeld says, her mentors were right about balancing the bench and bedside. “I would have regretted it if I couldn’t research while also seeing patients. If you never leave the lab, you don’t know what you’re missing.”

Your support fuels our vision to create a cancer-free world

Your support of cancer care and pioneering research at Ohio State can make a difference in the lives of today’s patients while supporting our work to improve treatment and reduce cases tomorrow.

Ways to Give