Solving the mysteries of CLL for leukemia patients

Blood cancer specialist Jennifer Woyach, MD, blends curiosity and persistence in studying chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

The life-or-death mystery confounded Jennifer Woyach, MD, whose team faced a puzzling setback involving a breakthrough drug that had stopped working in some patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Through scientific and clinical research, Woyach and her colleagues at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute (OSUCCC – James) had earlier developed a successful drug therapy called ibrutinib for CLL, the most common form of adult leukemia in the Western Hemisphere.

Before the scientists’ research helped lead to U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of the novel therapy in 2014, patients with CLL received first-line treatment with other drugs or drug combinations that were considered acceptable but failed to eradicate the disease, and the patients always relapsed.

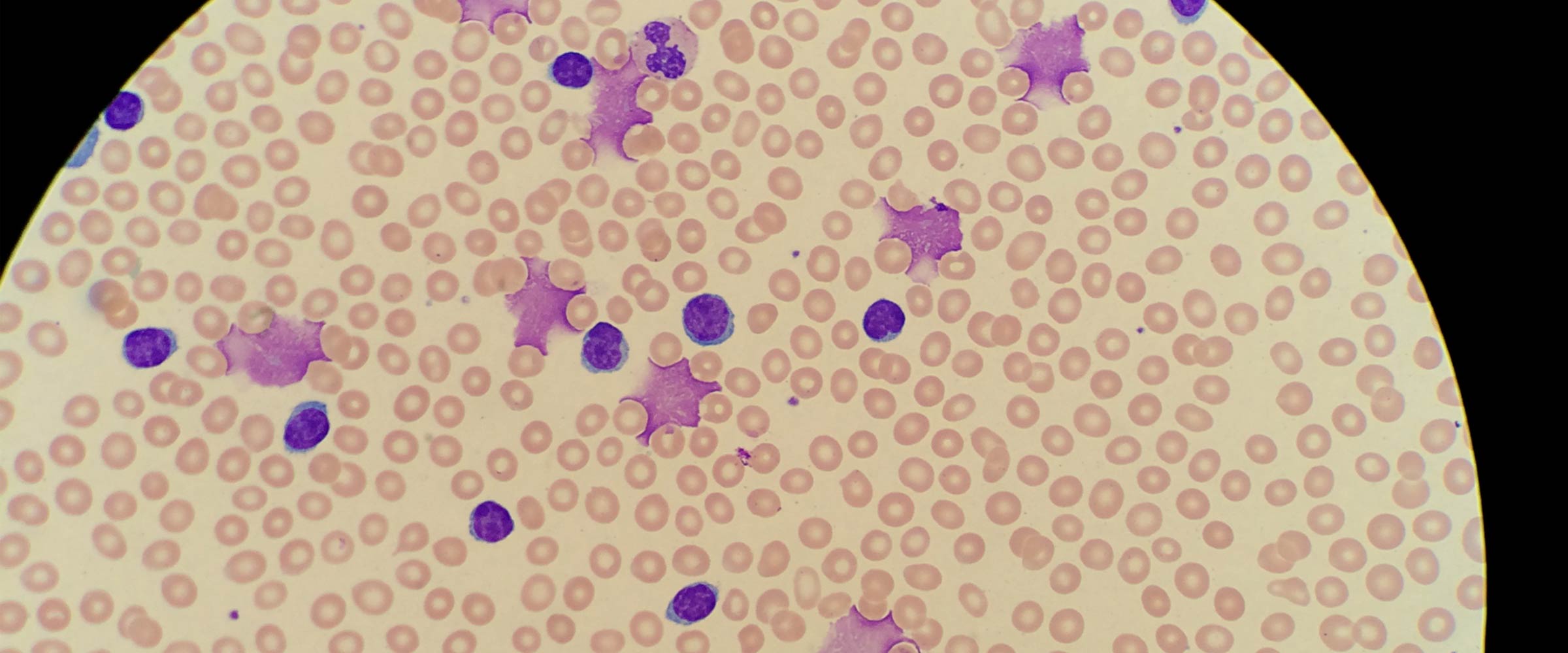

CLL, which is caused by bone marrow making too many lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell), was known to be an often slow-advancing malignancy that sometimes offered a life expectancy of several years to early-stage patients, but treatment with ibrutinib was now helping more patients achieve lasting remissions with more tolerable side effects, enhancing their quality of life.

Unexpectedly, the new drug therapy stopped working for two patients whose CLL recurred. Other patients also began relapsing. Most of those who relapsed eventually died.

For Woyach, confronting — and eventually helping to solve — the puzzle of why some patients on the new drug therapy suddenly relapsed was a difficult and critical moment on her journey to becoming a renowned medical oncologist.

“All doctors want to see their patients live longer and do well,” Woyach says.

“But we also know that, in the scientific process, sometimes things don’t work as well as you expected or would like, and you just have to work harder and smarter to make things turn out better in the future.”

Since joining The Ohio State University College of Medicine’s Division of Hematology in 2012, Woyach, who holds the D. Warren Brown Designated Chair in Leukemia Research, has played a major role in developing new targeted treatments that produce lasting remissions for many patients with CLL. Today, she co-leads the OSUCCC – James Leukemia Research Program.

OSUCCC – James scientists conducted much of the research that led to the FDA’s 2014 approval of ibrutinib for treating certain patients with CLL. Ibrutinib inhibits a protein known as Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) that is essential for the growth and proliferation of CLL cells.

“BTK is a signaling protein in CLL cells that is responsible for telling each cell to continue making copies of itself and to never die,” Woyach explains. “About a decade ago, it was demonstrated at Ohio State that when you block BTK in CLL cells, it’s like turning off a light switch. The cells cease to behave like cancer cells and eventually begin to die.”

Another breakthrough attributed largely to studies at the OSUCCC – James came in 2019 when the FDA approved the use of acalabrutinib — a second-generation BTK inhibitor — for first-line therapy in patients with CLL or small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL). It was the first full approval of this targeted therapy. Acalabrutinib more selectively blocks the BTK pathway without disrupting other key molecular pathways, thus preventing or minimizing side effects.

Unforeseen challenge prompts innovation

These targeted drugs have extended and improved the lives of many patients with CLL, which remains generally incurable and is managed like a chronic disease, but when some patients inexplicably developed resistance to the new therapies and relapsed, the plot took an unexpected turn.

“Since we were one of the first groups to treat patients with these drugs, we also were the first to see them stop working in some patients,” Woyach says.

She vividly remembers the first two patients they saw at the OSUCCC – James whose CLL had returned while taking ibrutinib.

By examining the patients’ blood samples, she recalls, researchers discovered that the BTK protein “light switch” had been turned back on in the cancer cells, and that further treatment with the targeted drug failed to deactivate the protein — a discouraging reversal of a therapy that had helped many other CLL patients.

“When we started using ibrutinib, it was mostly in patients with very refractory (resistant to treatment) CLL, where they had already gone through all of the standard therapies, and many of them had been on multiple clinical trials as well,” Woyach recalls. “It was really exciting that, when they were put on the ibrutinib clinical trial, the disease-related symptoms they’d had for many years suddenly went away, they went into deeper remissions, and months and years after they started taking the drugs they remained in remission.

“So it was very surprising when the first two patients relapsed,” she adds. “They both developed an elevated white blood cell count and progressively got worse over a few months, and then their disease escalated very quickly.

“Unfortunately, the treatments that were available for resistant CLL at that time didn’t work very well for them,” Woyach says. “And because these were among the first targeted therapies we had used in CLL, there was no framework in the disease for evaluating resistance.”

Sadly, she says, many of those early relapsed patients died, prompting the researchers to quickly search for the root of this surprising problem. “We hoped that if we could find and understand the mechanism of drug resistance, we might be able to tailor an effective and tolerable therapy.”

Rolling up their sleeves

Though confounded, she and her colleagues were undaunted, knowing the lives of many CLL patients depended on finding another breakthrough.

After confirming in the lab that the BTK protein in sample CLL cells had turned back on and remained on despite the presence of ibrutinib, the researchers surmised that a genetic mutation had developed that prevented silencing the BTK pathway.

Working with collaborators at Duke and Cornell universities who had expertise in CLL cell sequencing, as well as with the company that made ibrutinib, Woyach’s team conducted DNA sequencing on the patients’ blood cells and identified the acquired mutation, which they found to be a common mechanism of relapse.

“Once we identified the mutation, we were able to design experiments to see that, indeed, the particular pathway we were targeting before was still active, which suggested we could target it again if we had a drug that would work in the presence of the mutation,” Woyach says. “That led us down the pathway of looking at agents called reversible BTK inhibitors, which are working really well for these patients now.”

She explains that ibrutinib works by forming a covalent chemical bond (in which two atoms share their electrons) with BTK, creating a permanent link between the drug and the protein, and irreversibly thwarting the protein’s ability to signal.

But when a genetic mutation foiled ibrutinib’s effectiveness, Woyach says, the researchers pursued reversible BTK inhibitors. Unlike irreversible BTK inhibitors such as ibrutinib, reversible BTK inhibitors form a noncovalent chemical bond with the target protein. (Noncovalent bonds form by exchanging rather than sharing electrons between two atoms, or by involving no exchange.)

“Our group, working with companies that manufacture these inhibitors, was the first to show that the new reversible BTK inhibitors are active in CLL patient samples that are resistant to ibrutinib,” Woyach says. “We are now working with a number of new drugs that look very promising in the laboratory for relapsed patients who do not have other good options for therapy.

“Some of these drugs are already in clinical trials and are looking really phenomenal,” she adds. “The patients are responding very well, having longer remissions and only mild side effects.”

Approaching her work with wonder

Her team’s ongoing work to help patients with relapsed CLL is a testament to Woyach’s fascination with medical science and her persistence in seeking solutions to perplexing problems. Her passion for finding the answer to difficult questions developed during childhood.

Her mother is a retired medical technologist who worked for many years at an area hospital; her father has a PhD in political science and is a senior lecturer in International Studies at Ohio State; her brother studied computer science at the University of Southern California; and her sister has a PhD in electrical engineering and works for Google.

“My parents instilled a strong work ethic in me and also taught me to always be curious about the world around me,” Woyach says.

Her incessant curiosity has fueled her medical career, which once was headed in a different direction. Initially, the Columbus native wanted to pursue family practice or general internal medicine because she “liked the idea of taking care of patients for many years.”

But during an oncology rotation in her third year of medical school at Ohio State, the rapidly evolving science of hematology/oncology altered her aspirations. She found herself drawn to both the prolonged rapport that oncologists have with their patients experiencing cancer and to the burgeoning biological understanding of cancer in its many forms.

“I realized that this is a specialty where you can develop long-term relationships with patients and their families at a critical time in their lives to provide education, comfort and hope,” says Woyach, who specializes in treating patients with CLL and B-cell lymphomas. “I also liked how quickly this field was changing as we were starting to better understand the molecular basis of different cancers and using this knowledge to develop new targeted therapies.”

Unwavering commitment to career and family

Now a full professor, Woyach is also the Division of Hematology’s leader for CLL and hairy cell leukemia, and associate division director for clinical research. In May 2021, she accepted an additional job as co-leader of the Leukemia Research Program at the OSUCCC – James, sharing that role with Ramiro Garzon, MD, a professor in the Division of Hematology who acknowledges Woyach’s skill as a scientist and leader.

“Dr. Woyach has been leading the development of novel therapies for CLL that have changed the way we treat this disease,” says Garzon, who holds the Bertha Bouroncle, MD, and Andrew Pereny Chair of Medicine at Ohio State. “Her accomplishments are recognized by her publications in top journals, funding and leadership at Ohio State, and in national and international cooperative groups.”

It’s a huge amount of responsibility, especially when paired with Woyach’s other role as a wife and mother. She and her husband, Dan, a deputy director at the Ohio attorney general’s office, have two young children, Sammy and Ellie, but the couple are adept at balancing work and family.

“Outside of work, most of my time is spent with my children, husband and our families,” she says. “We like to travel and explore new places. During the COVID-19 pandemic, we’ve been going to metro parks around Columbus.”

Woyach also acknowledges her exceptional medical training and the many people who have influenced her career, especially John Byrd, MD, a former Distinguished University Professor in the Division of Hematology and senior adviser for cancer experimental therapeutics at the OSUCCC – James.

“My mentor since residency was Dr. Byrd. He has been instrumental to my career success,” says Woyach, whose interest in targeted CLL therapies and acquired resistance began when she worked with Byrd in the clinic and later in the laboratory.

“He was great at giving me opportunities to lead projects, or to take my thoughts and ideas to the next level,” Woyach says. “He provided guidance and helped shape my projects without taking them over. He was exactly what a mentor should be.”

Age: Another avenue of interest

A focus that parallels Woyach’s interest in targeted therapies is her work in treating elderly patients with CLL, which is especially important since the median age at diagnosis for this disease is 70-72. She has been studying older CLL patients since she was a postdoctoral fellow.

“Older patients often have multiple co-morbidities (simultaneous presence of diseases or conditions) or are on other medications and tend to have different side effects than younger patients when treated with chemotherapy, for example. Having agents that are well-tolerated in the older population is crucial in a disease that primarily affects the elderly,” Woyach says.

She devotes much of her research to helping patients contend with their disease and live as normal a life as possible. Among her early successes in this area was leading a multi-institutional clinical trial that demonstrated how previously untreated patients with CLL who are over 65 had a significantly lower rate of disease progression when they received ibrutinib rather than the drug combination of bendamustine plus rituximab — a regimen that was considered one of the best for these patients.

Results of this head-to-head comparison of treatments were published in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine, and the study also earned a 2020 Top Ten Clinical Research Award from the Clinical Research Forum, which provides leadership to the national clinical and translational research enterprise.

Woyach now chairs a multi-institutional study that is investigating continuous versus intermittent targeted therapy in the same patient population — work that’s in the context of her national role on the Leukemia Committee and the Cancer in the Elderly Committee of the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology.

She points out that these studies have global relevance.

“Prior to 2018, few trials were focused on older patients,” Woyach explains. “That’s changed, and now there are a lot of trials specifically involving either older patients or patients with multiple co-morbidities. What’s really important about these trials is that they are applicable to patients that oncologists may see in clinics everywhere, not just to patients we see at Ohio State or any other single institution.”

Improving the overall outlook

Woyach believes that she and her colleagues at the OSUCCC – James will continue contributing to advances against blood cancers, offering even greater hope to patients with these illnesses.

“Ohio State is already a destination site for many diseases, and I think with our faculty, staff and resources, we have the opportunity to be one of the world’s top sites for treating blood diseases and blood cancers,” she says.

“Dr. Garzon and I are working with the OSUCCC – James and the Division of Hematology to recruit more faculty to complement the outstanding physicians and scientists already here, and to increase collaboration within the group.”

Her hope for the future of the Leukemia Research Program is its sharp focus on targeted therapies and immunotherapies that are both effective and tolerable. “We’re very much on the forefront of these transformative therapies that are really going to make a difference in patients’ lives,” she says.

And that’s what propels her forward.

“What really keeps me coming back each day is that I can see things our group is doing in the research setting that can be directly applied to clinical care,” she says. “I want to continue doing impactful work that, by offering more tolerable therapies and by preventing or treating disease complications, will help patients with CLL live not only longer, but better.”

Your support fuels our vision to create a cancer-free world

Your support of cancer care and pioneering research at Ohio State can make a difference in the lives of today’s patients while supporting our work to improve treatment and reduce cases tomorrow.

International leaders in blood cancers

The OSUCCC – James is dedicated to developing and conducting outcome-based research that advances treatments for patients with CLL.

Learn more about CLL research