Expanding access to advanced robotic surgery for lung cancer patients

Robert Merritt, MD, is pioneering robotic-assisted surgery to give more lung cancer patients an improved outcome and faster recovery.

Unlike what you see on TV, the lights aren’t a bright, glaring white in this operating room on the fourth floor of The James Cancer Hospital and Solove Research Institute.

Instead, Robert Merritt, MD, sits in a dimly lit corner, peering intently through the eyeholes of a large console, where he expertly controls hand levers and foot pedals.

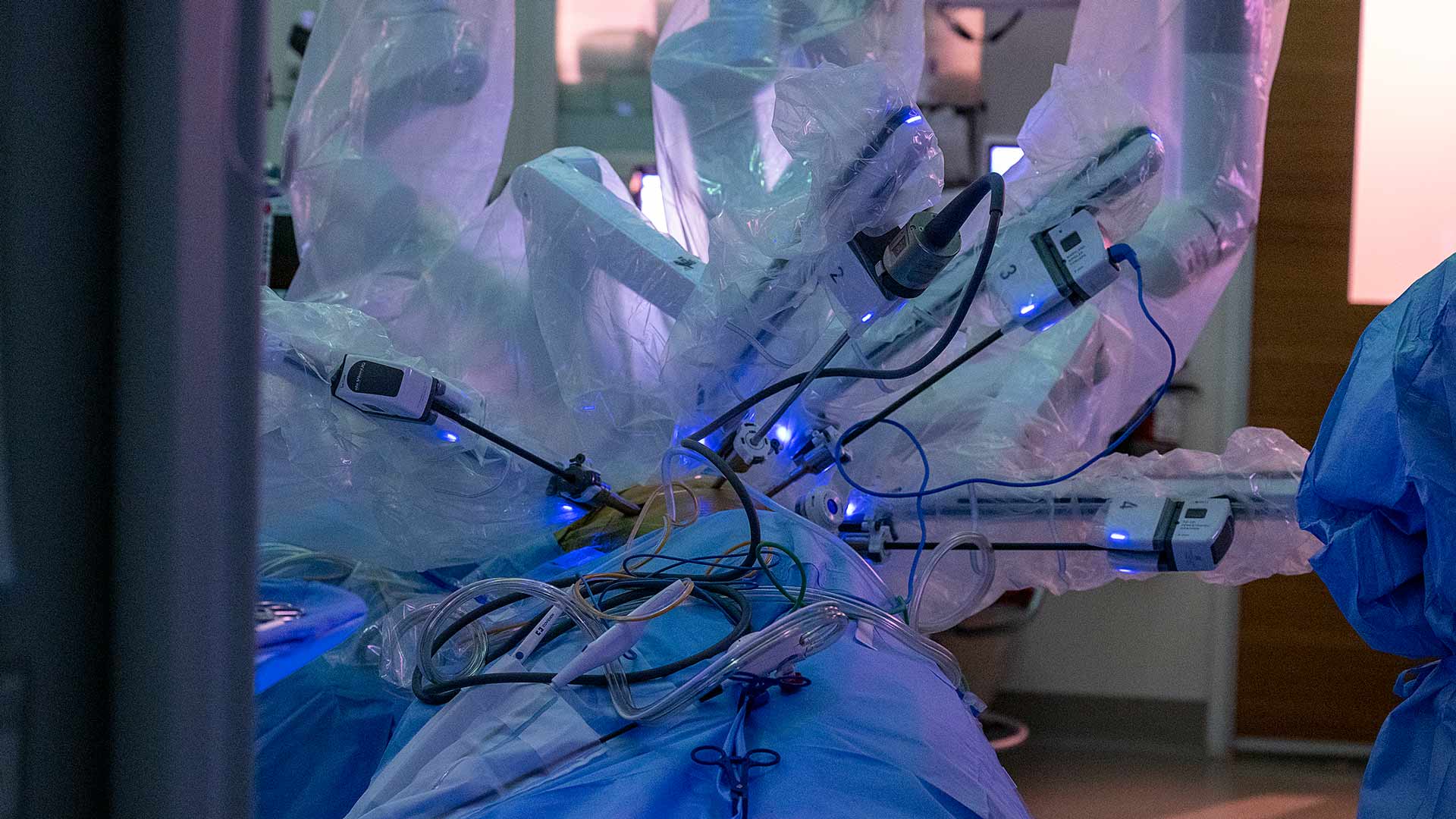

A 68-year-old patient with a growth in her left lung lies in the center of the room surrounded by the surgery team, only her side exposed, with the spider-like metal arms of robotic surgery tools attached to cameras and positioned in her chest through four small incisions. They move in coordination with Dr. Merritt’s hands as large monitors near the ceiling allow the team to observe what’s happening inside her left lung.

It’s mostly quiet except for a beep with each snip and cauterization as Dr. Merritt controls the tools of the surgeon’s trade to remove the disease and surrounding tissue.

Then the beeping pauses: Dr. Merritt, still focused on the console, uses a microphone to discuss the lung’s anatomy with his physician assistant. This growth couldn’t be in a worse place.

This is when Dr. Merritt calls on his trademark composure, his patience and the experience of performing more than 1,000 robotic-assisted surgeries. More highly magnified cameras are inserted, and the anatomy is digitally marked on screen. Dr. Merritt’s team feeds rubber tubing and additional items into the lung through an access port, and he uses these tools to further separate the growth from the lung.

He steadily makes the final cuts, and the diseased section of the lung is removed.

Improving outcomes and recovery for lung cancer surgery patients

Dr. Merritt is a thoracic surgeon at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute (OSUCCC – James) and director of the Division of Thoracic Surgery at The Ohio State University College of Medicine’s Department of Surgery.

In his role, he’s championed robotic-assisted surgeries of the thoracic — or chest — region, including the lung and esophagus. He specializes in surgically treating early stages of non-small cell lung cancer and other lung diseases.

The robotic method is less invasive, Dr. Merritt explains, than traditional surgeries, in which long incisions down a patient’s chest are needed to open and spread the sternum and rib cage. With robotic-assisted surgery, most patients go home two to three days postsurgery and return to normal activities within two weeks, compared with a week in the hospital and two months of recovery with open-chest surgery. This further allows patients who may also need chemotherapy, radiation or other treatments to start those therapies sooner.

The current robotic method, using the da Vinci surgical system, provides three-dimensional visualization with normal depth perception, Dr. Merritt says, and he expects the technology to only get better.

“In terms of the future, I think there will be new platforms from other companies, so there’s going to be some pretty rapid improvements,” he says.

Along with reducing recovery time, Dr. Merritt says robotic-assisted surgery reduces pain and complications.

“The other great thing about this technique is that we can offer it to elderly patients, patients without perfect lung function,” Dr. Merritt says. “It just opens up more opportunities to provide surgery to higher risk patients.”

Today, only 14% of early-stage lung surgeries in the United States are being performed using this technique.

Building a high-volume robotic lung surgery program

At Ohio State, the surgical team is hoping to change that, showing that the minimally invasive method can manage not only lung cancer but also esophageal cancer, says Dr. Merritt’s colleague Desmond D’Souza, MD, assistant professor of Thoracic Surgery at the College of Medicine.

“Bob has been instrumental in spreading the word that robotic surgery can be done safely, it can be done efficiently and it can be done without compromising surgical principles,” Dr. D’Souza says.

Ohio State has been performing robotic thoracic surgeries since 2016 and currently completes about 435 such surgeries per year, including about 200-250 in the lungs, making it one of the largest programs in the country.

This vast experience means that fewer than 3% of these surgeries become too difficult to complete with the robotic approach and are converted to open-chest surgeries, far fewer than the typical 15-20% rate.

Dr. Merritt’s proficiency with the technique has resulted in his inclusion on a panel helping to develop the next-generation surgical robot.

He says he was drawn to OSUCCC – James eight years ago by its collaborative nature, and he appreciates how surgery teams work alongside oncology and radiation experts to ensure patients receive individualized, evidence-based, state-of-the art care tailored to each specific case, regardless of stage.

“We’re aware of all the latest treatments and findings, we’re aware of the latest science and surgical techniques. We’re at the forefront of that,” Dr. Merritt says. “That’s what differentiates us: research, science and innovation.”

Beating the odds against lung cancer

John “Coach” Johnson was a graduate assistant for the Ohio State football team under head coach Woody Hayes in the 1970s. He also was a boxing manager, leading Buster Douglas to his 1990 championship bout over Mike Tyson against 42-to-1 odds. He has many heroes, and considers Dr. Merritt one of his greatest, so much so that he plans to honor him at his inaugural 42-to-1 charity dinner planned for 2024.

Johnson recalls the doctor coming into his hospital room after a 2019 surgery to remove cancer from his right lung. Dr. Merritt had a positive attitude and what Johnson calls an “Archie Griffin smile,” referring to the two-time Heisman Trophy winner who played for Ohio State and the Cincinnati Bengals.

“We were talking about boxing and talking about fighting, and he said, ‘You know, Coach, my team and I go into the OR every day and fight to keep people alive,’” Johnson says.

“That’s a pretty serious fight.”

It was a cardiologist who brought Johnson and Dr. Merritt together. Johnson had quit smoking years earlier, but as a former smoker, he was eligible for a lung cancer screening, and the cardiologist referred him for a computerized tomography scan. Nothing showed up, and he returned a year later for another CT scan, which revealed a nodule. Three months later, it had grown: lung cancer.

Johnson says his fear turned to confidence after he met Dr. Merritt. Both knew he’d faced much stiffer odds in the past.

At age 75, open surgery would have been especially risky, so Johnson was an ideal candidate for the robotic technique. Dr. Merritt was able to remove the cancer, and four years later, there’s no sign of it recurring.

Making an impact

Dr. Merritt grew up in southern Illinois, the son of teachers. His mother taught math and science, his father taught English. He leaned more toward math and science. It was a dentist uncle who first piqued his interest in the medical field.

He specialized in lung cancer because he wanted to walk alongside patients as they either became cancer-free or faced recurrence.

“When patients come in with lung cancer, they’re terrified. The world’s been turned upside down, and it creates a lot of anxiety,” he says. “When you perform surgery, they get cured and they come back five years later still cancer-free: those are the cases that reaffirm that I chose the right specialty — just seeing how you’re giving them a second chance at life.”

Married to a pharmacist with whom he has twin 13-year-old children, Dr. Merritt finds time for little more than his 12-hour workdays and his family. Competing in an Ironman Triathlon remains on his bucket list. But, for now, he considers his office his locker room.

Exploring disparities in lung cancer outcomes

Lung cancer is the No. 1 cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States and the world, but research remains underfunded, due to the stigma of smoking and the blame often placed on patients, Dr. Merritt says.

While many lung cancers are linked to smoking, 15% occur in patients who never smoked.

Along with his research on robotic surgery outcomes, Dr. Merritt has explored why certain cancer survival rates for Black patients are worse than their white counterparts.

His findings uncovered that Black patients with operable esophageal cancer have three times greater odds of not being recommended for surgery, when compared with white patients.

A separate study shows that Black patients with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer had significantly higher survival rates if treated at an academic medical center, when compared with treatment at a community facility. The odds of Black patients undergoing surgery were higher at academic facilities compared to community facilities.

Dr. Merritt says factors may include unconscious bias, which impacts communication, access to medical centers, travel barriers and other social determinants.

Further, Dr. Merritt adds, while patients may trust and identify more with physicians with similar backgrounds and experiences, people of color are underrepresented in the field of surgery.

Additional recruitment and mentorship efforts, he says, are needed to help address challenges faced in this area.

Dr. Merritt himself serves as a mentor and leads by example, demanding quality work but allowing his team the space to grow and achieve goals, Dr. D’Souza says.

“He’s often the first to arrive and the last to leave. It’s hard to find anyone who’s worked harder than Dr. Merritt, to the point that he’s always here,” Dr. D’Souza says. “He’s always taking care of patients. He’s always available, affable and very able — and the makings of a good surgeon are those three A’s.”