From science fiction to reality: Using CAR T-cell therapy to turn a patient’s own blood into a cancer-fighting weapon

On the surface, the idea sounds like science fiction: extracting a cancer patient’s own white blood cells, reengineering them in a lab, and injecting those cells back into the body to target and destroy cancerous cells.

But in recent years, the concept has become a reality for some people with blood cancers, such as leukemia and lymphoma.

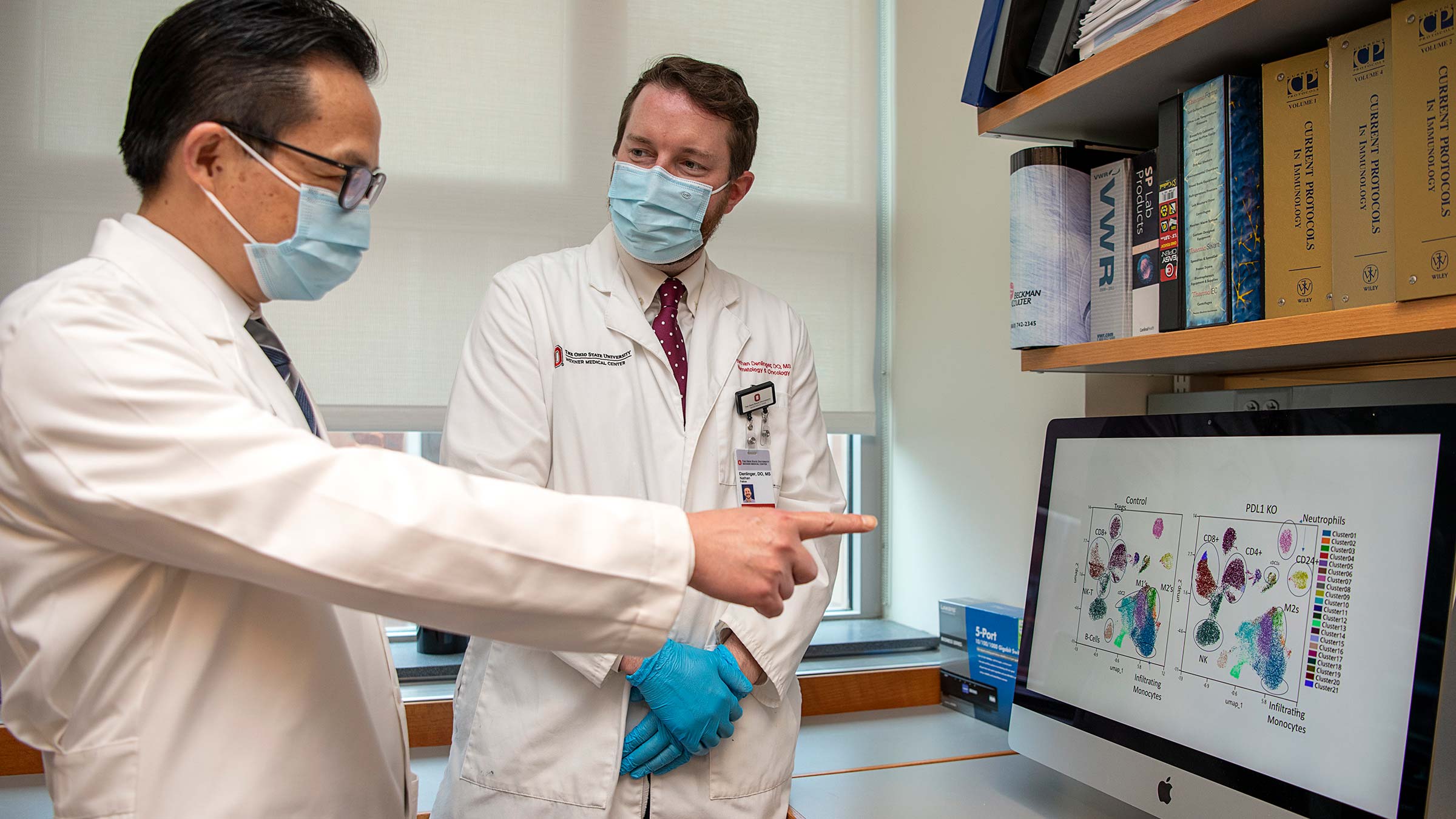

“Cell therapy-based treatments have shown considerable promise,” says Yiping Yang, MD, PhD, a professor of Internal Medicine and director of the Division of Hematology at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute (OSUCCC – James).

Known as CAR T-cell therapy, the method involves removing white blood cells (called T cells) from the patient’s blood.

Then, in a lab, specially trained experts place a chimeric antigen receptor (or CAR) on the cells’ surface to retrain them to identify a specific cancer-signal on that surface. Doing so allows the CAR T-cells, once infused into the patient, to recognize and destroy cancer cells.

Every person’s disease is different, with individually unique genes and molecules driving that disorder, and the highly personal CAR T-cell therapy has proven to deliver lasting remission for about 30% to 40% of patients who receive it.

The reason for that encouraging success rate?

“Tumors find a way to evade the immune system,” says Yang, likening the challenge to bacteria that develop resistance to antibiotics. “CAR T-cell therapy is mechanically different from conventional chemotherapy; it is genetically engineered for that patient.

“Now, it’s a fight between the immune system and the tumor.”

‘Tremendous’ promise for immunotherapy cancer treatment

Although Yang wasn’t working at Ohio State when the earliest CAR T-cell treatments were administered as part of clinical trials in 2015, he was a co-director of hematologic malignancies and cell therapy program and professor at the Duke Cancer Institute and Duke University School of Medicine, which also had begun administering the new treatment in clinical trials.

Yang, who now holds the Jeg Coughlin Chair in Cancer Research at The Ohio State College of Medicine, specializes in the treatment of lymphoma, leukemia and virus-associated malignancies, has devoted his career to researching cancer immunology and immunotherapy.

Which is why the initial results of CAR T-cell therapy trials were so emotional and validating.

“At the time, we had nothing else to offer other than chemotherapy, so we were very cautious about this new therapy,” Yang says. “Suddenly, our patient responded. The response created a tremendous amount of excitement throughout the community.”

Yang carried that enthusiasm to Ohio State with his arrival in 2019 — as well as two National Institutes of Health-funded research studies focused on strategies for cancer immunotherapy in stem cell transplant and research of T memory stem cells, and tumor-infiltrating T cells, respectively.

He’s also become involved with the newly established Pelotonia Institute for Immuno-Oncology (PIIO), a comprehensive bench-to-bedside research initiative, as a principal investigator and an internal advisory board member.

The institute, launched at Ohio State in 2019, has a shared goal: work collaboratively to study, develop and evolve an array of groundbreaking treatments for all types of cancers.

“There are many labs associated with the PIIO tackling the different aspects of these immune evasion mechanisms,” Yang says. “The likelihood is that we’ll have newer therapies in the coming years and decades, and the momentum we feel here is that we can eventually conquer cancer.”

Improving CAR T-cell therapy success rates and side effects

Approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2017, CAR T-cell therapy is a form of immunotherapy that harnesses the body’s natural defenses to fight cancer.

In the case of CAR T-cell therapy, potential patients are usually those who have failed on conventional chemotherapy treatments. Having the option of CAR T-cell therapy has brought new hope to patients and their loved ones.

Today, OSUCCC – James clinicians can point to success stories from their own backyard. One of them is a central Ohio man with lymphoma who could “literally feel the tumor shrinking” in his throat shortly after receiving CAR T-cell therapy in 2016; he’s still in remission.

While CAR T-cell therapy has minimal side effects for most patients, doctors are trained to look for these warning signs, Yang says, and patients can be safely monitored throughout their CAR T-cell therapy journey.

It’s a path that he and other researchers hope to see become more traveled.

“A lot of patients have long-term remission,” Yang says. “It shows how powerful this new therapy will become.”