Behind the scenes: Ohio State’s blood bank

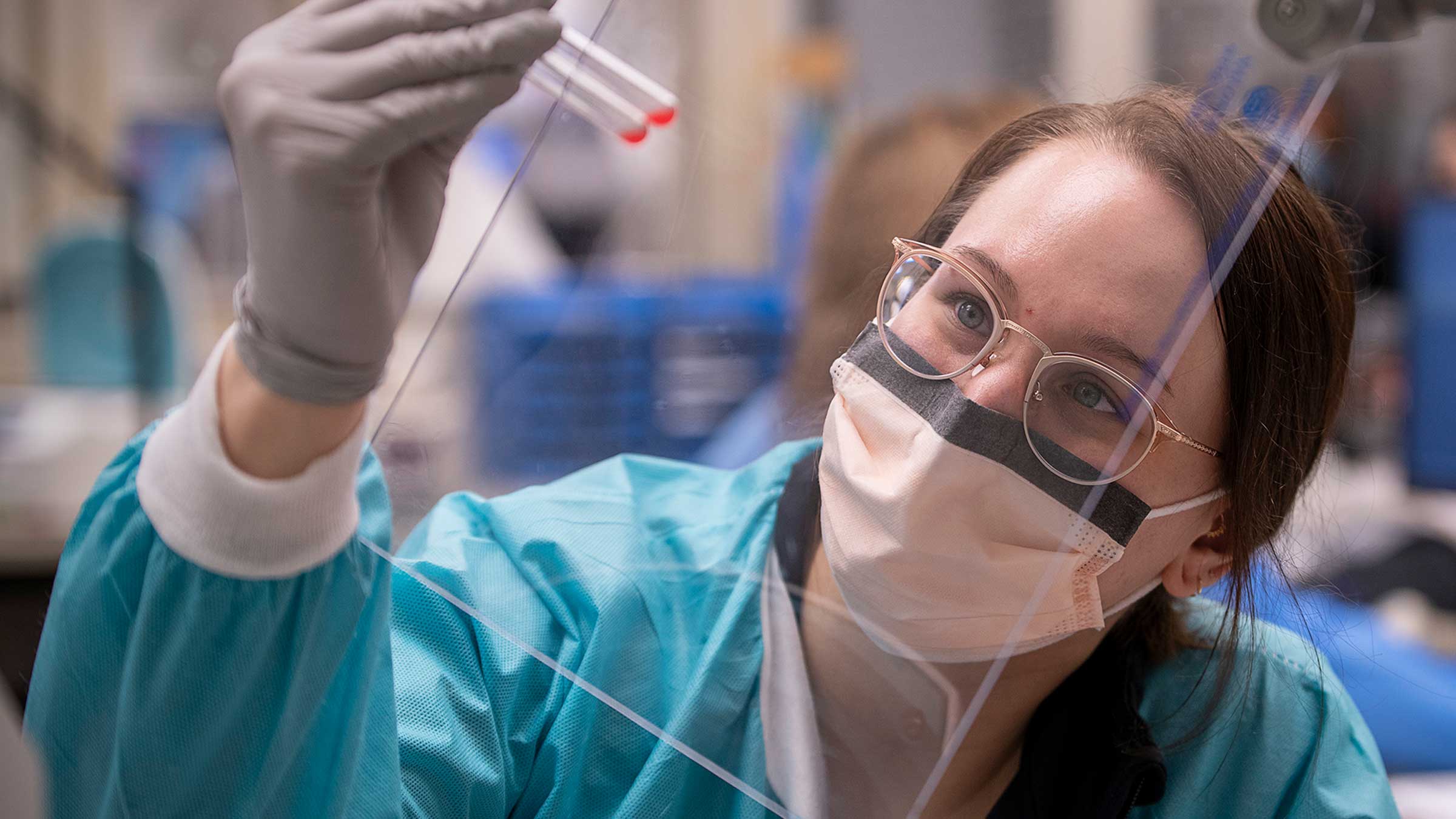

Take a look at what happens in the Ohio State hospital blood bank, where technologists take critical steps to ensure patients stay safe during blood transfusions.

The blood bank at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center issues about 6,000 units of blood products for patient transfusions every month — roughly 200 units each day.

They may be used to save someone severely injured during a car crash, or to help a patient thrive after a kidney transplant. They might help a new mom recover enough to hold her baby after a difficult delivery, or ensure a cancer patient has the strength to return home after an especially rigorous outpatient treatment.

Scott Scrape, MD, medical director of Transfusion Medicine, offers a behind-the-scenes look at the blood bank, located at University Hospital, where lab technologists perform about 42,000 tests every year to make sure that each patient receives the appropriate type of product as quickly as possible.

Inside the blood bank

The first sight visitors to the blood bank encounter is the issuing window, which is actually the last step in the blood bank’s matching and delivery process. It’s here where staff issue products to nurses and other health care workers, who carry them to the floors where they’re transfused to patients in need. Each unit is delivered with paperwork and labeled to guarantee it reaches the intended patient.

As Dr. Scrape steps through the nearby entrance, he’s greeted by the hefty door to a walk-in refrigerator that holds about 800 units of red blood cells, what most of us envision when we think of blood transfusions. They’ve been sorted and tagged by technologists and placed in red bins, and they’re stored between about 34 F and 43 F, with a shelf life of 42 days.

Across the room, in the middle of one wall, Dr. Scrape points out a cluster of plastic containers sitting ready to deliver products through a tube system that carries products to various areas of the hospital.

Nearby, large machines work away, analyzing blood samples from patients to determine the type and screen for antibodies.

An agitator that resembles a tightly packed bakery rack gently rocks platelets at room temperature in a tall blue cabinet. Dr. Scrape explains that these products last about five days after they’re donated, or about three days after they’re received by the hospital from supplier Versiti Blood Center of Ohio.

Around the corner, another, larger cabinet stores packets of frozen plasma in wide drawers. These units can stay in the freezer for up to one year. Before they’re used, they’re thawed in a warm water bath for about 25 minutes. From there, they can be used for up to five days.

A busy multi-station crossmatching area is where patient blood ends up if the automated typing and screening system discovers any antibodies, which are present in the blood of about 10% of people. Technologists must identify which antibodies are present and ensure the units provided don’t carry antigens that will trigger those specific antibodies to attack in the recipient’s body, Dr. Scrape says. If that happens, the body will reject the blood.

Finally, an intake area near the back of the blood bank is where the process begins. This is where the typing of newly received blood products is confirmed. They arrive from Columbus-based Versiti, with frozen products packed on dry ice, refrigerated products packed on wet ice, and platelets with room temperature packs. Technologists make sure every product is recorded in the hospital system and recognized before being passed along to be placed in the refrigerator, freezer or agitator.

Blood matching requires thorough process

If no antibodies are detected in a patient’s blood, the matching process takes about 75 minutes, says Diane Geren, the blood bank’s assistant manager, and Christa Hensley, education lead. If antibodies are detected, it takes at least a couple more hours to identify what those antibodies are. From there, technologists determine if needed blood is part of the hospital’s inventory. If it’s not, the blood supplier might have to screen for and send the needed units, which adds additional time. On occasion, a rare type may require a rare donor program search, which can take up to three days.

It's critically important that no corners are cut, because an incompatible blood transfusion can be fatal, Hensley says. It also can cause damage to organs, especially kidneys.

In emergencies, there are processes in place that allow patients to receive the best match possible with the information available, so-called “universal donor” O-negative blood. Following the procedures for other patients is vital so those units can be reserved for patients in critical need, Geren explains.

Blood donations becoming scarcer

To keep the refrigerator, freezer and agitator full, product must consistently be delivered to the intake area. As blood donations have waned over the past couple of years, concerns over supplies have become commonplace.

While 40% of the population is eligible to donate blood, only 3% actually does, says Dr. Scrape, a clinical associate professor of pathology at The Ohio State University College of Medicine.

There's a constant need to have regular donors to ensure inventory is stable. Donating during times of crises helps, but there’s really a need for “blood on the shelves” when emergencies strike, Hensley says. The blood that's already at the hospital, she says, is the blood that’s going to save someone who's in a trauma situation.

Ready to donate blood?

Find a blood drive today.

DONATE