Love in the lab: Scientist couple finds enduring chemistry

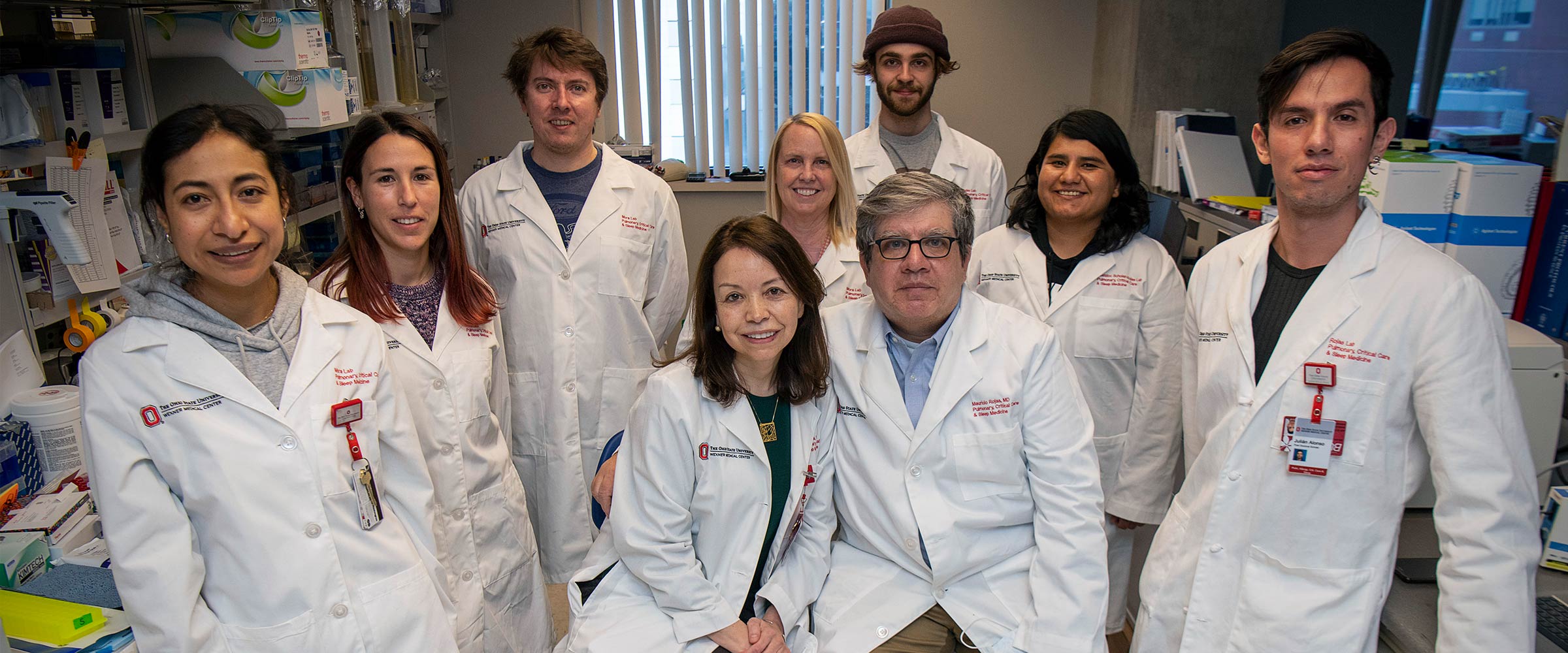

Ana Mora, MD and Mauricio Rojas, MD, know what it means to balance work and marriage. As married research scientists at The Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, the two not only share a home together but also work side-by-side in the same research lab.

“Conflict?” Mauricio Rojas, MD, grips his chin with his hand and rests an elbow on the table. He’s stumped.

He can’t think of what to say about how he and his wife Ana Mora, MD, deal with conflict, because, well, they don’t have much, he tries to explain. That’s even though they’ve worked together for 27 years, often in the same lab or across the same academic hallway, and at the beginning of the pandemic, at the same rectangular wood table in their house.

Mora looks toward the ceiling trying to recall times she and her husband of three decades have clashed.

Both are researchers at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center who study how the lungs recover from injury. Their offices are a couple floors apart. But they share a lab and spend at least half of each workday in the same virtual meetings or in one of their offices together writing grant applications and reporting on their research findings. Every day, they have lunch together. Rojas walks up to Mora’s office because she’s got an espresso machine and has a steaming cup waiting for him.

Today Mora sits a few feet away from Rojas at a table in her fifth floor office with a view of a new hospital tower that’s rising up and just might block some sunlight when fully built. But today it’s bright in her office and she looks directly at Rojas. Her light brown eyes meet his green eyes as they try to explain what might mystify a lot of people: that they can work together, live together, spend so much time together and, yet, still get along.

“Let’s just say in our life, conflict is very, very rare,” Rojas says.

Which isn’t to say they are always in sync. Occasionally Mora tells Rojas to turn down his music when she’s trying to write because without her contesting, he’d likely play the same genre of music a little too long and a bit loud.

“I can’t write if his music is too loud,” Mora says.

“And I can’t work without music,” he adds.

While Mora writes, she often says the words aloud, and her keyboard clicks when she taps on each letter. That can be distracting for Rojas. And when he asks her opinion on something, she doesn’t respond if she’s writing. She’s too zoned in to what she’s thinking about to even hear the question. He repeats it.

Working together, working apart

When the pandemic began, they sat at the same table together in a spare room of their home, which was in Pittsburgh at the time. That lasted a couple of weeks. They weren’t exactly clashing over the music or the keyboard clicking, just maybe annoyed with each other for fleeting moments, then back to work. Neither of them gets angry easily, and if they do, they never stay mad, which perhaps is part of the magic of how it all works. They get it out. They move on.

Rojas moved on, literally. A couple floors down to the wine cellar where it was quite comfortable, he says. They just realized what a lot of couples working at home have during the pandemic, if they hadn’t before: Separate rooms are better.

“When we started working together 30 years ago, we were doing research shoulder to shoulder in the same lab. We were doing everything in the lab together,” Rojas said.

Over the years, their togetherness at work has ebbed and flowed. At times, they’ve focused on different but complementary subjects — Mora studying T cells, Rojas studying B cells. Both cells are involved in immunity.

For the past decade, they’ve studied how aging hinders the lungs’ ability to recover from injury. Now at Ohio State, while they’re not shoulder to shoulder in a lab, they work more closely than they have in a while.

“Ana has my interests,” Rojas says. “And I have hers.”

Where their interests intersect

Rojas studies the possibility of using stem cells to help patients with severely injured lungs. Mora’s research focuses on how the mitochondria in lung cells function as people age, leaving some more likely to develop chronic lung diseases.

Though they share a lab down the hall from Rojas’s office, mostly they work outside the lab but still together. They write about their findings, often in jointly authored papers, and when they do, Mora might take Rojas’s first draft and cut, reword, paste and add a whole lot more detail.

“We are very different,” Mora says. “We see a problem in totally different ways.”

He’s more intuitive, talented in the big picture; she, more focused on the small details, what’s happening within cells.

He’s extroverted, loves talking to colleagues, talking to anyone. Mora tends to be more quiet. She likes the writing part of her job better than the talking.

She’s a strong writer, Rojas points out. Much better than he is. She smiles. He might be overstating it a bit, she says.

Like when he recalled the results of a final exam they took in medical school at the National University of Colombia in Bogota. Rojas’s friends congratulated him for getting what they thought was the top score in the class, then he found out her score. It was even higher. Wow, he thought, she’s incredible.

Growing up together

Before medical school, they were undergraduates together at National University of Colombia, where only 10% of the entire first-year class was female. Those women all sat at the front of classes, while the men filled the other seats. It may be the women wanted to be sure they caught everything that was said, every detail. This was their chance.

A mutual friend introduced Rojas and Mora. It was during the first week of classes, their freshman year. Rojas remembers what Mora was wearing that day, a sweater with wide bands of horizontal purple and gray. Her dark hair was long and curly. They said ‘Hello, how are you?’ That was it.

A couple years later, Rojas drove to Mora’s parents’ house to pick up Mora — and her date. His date was in the car as well, along with another friend, also matched up. At the party they all attended, Mora and Rojas struck up a conversation that stretched on and on as the dates they had arrived with drifted into the periphery.

“I was very shy,” Rojas says. “No, never shy,” she says about him. She considers herself the introverted one.

It may be that Rojas and Mora thrive on doing almost everything together because from early on, they’ve been together. They started dating when they were 20, graduated together, went on to medical school where they commuted in Rojas’s car each day. After classes and on weekends, they studied together. Every day of medical school they had lunch together: one sandwich, one small pound cake, two Cokes. They split everything.

For a short period after medical school, the couple that had spent about 10 hours of every day together — taking classes, studying, commuting — were apart for nearly three months. Rojas flew to New Delhi, India, for a class in the molecular biology of viruses. That was long before texting, Facebook and email. Phone calls cost too much. They communicated with each other by fax.

Happier together than apart

That separation convinced them about what is still true in their relationship now: that they do far better together than apart. Shortly after Rojas returned from India, he asked Mora to marry him.

In the 31 years since they married, Rojas can remember the very few times they spent more than just a couple of days away from each other. The last time was 27 years ago. Both Rojas and Mora were offered post-doctoral positions at Vanderbilt University where they’d study HIV vaccines. The university wanted Rojas to start on March 1. It would have to be after March 18, he told his new bosses. It would have to be after his wedding anniversary. They agreed.

Now those stretches of time away from each other only last a couple of days, maybe a week or so if Mora visits her mother in Colombia. All the other days, their time is woven together, starting each day with breakfasts that last about 40 minutes with music, orange juice, coffee, fresh bread. Even when their daughter was young, they always had long breakfasts. Rojas gets up early to make breakfast, and the entire time they talk to each other, their phones and laptops out of reach. They talk about the books they’re reading, about their daughter’s upcoming wedding, about the news, about work.

“Maybe the secret is we talk. A lot,” Rojas says. “About everything.”

“We care a lot about each other, about each other’s happiness,” Mora says, explaining what she considers part of the magic of their relationship. “One of my main priorities is Mauricio. Is he doing well? Is he happy?”

When Spain was in their sights

Over the 31 years they’ve been married, they can think of only one period when they clashed for more than just fleeting moments. Go all the way back to 2009. They were both living in Atlanta working for Emory University, when Rojas got a job offer in Barcelona. They had a chance to move to the country they had long been enamored with. Visiting Barcelona, they worked with a real estate agent to find an apartment with a view of the Mediterranean Sea. Their daughter would be able to go to a top school there.

While Rojas was imagining Barcelona’s beaches and its vibrant nightlife, Mora hesitated. Sure, the city was an idyllic place to live, but her job offer wouldn’t be a step up. She would be a research assistant for Rojas. Career-wise, it wasn’t the right move for her.

“We never had a fight over it,” Rojas is quick to point out. “It was just stressful.”

After several days of back and forth weighing their options, they decided not to go with Barcelona. They opted for another offer, faculty positions at the University of Pittsburgh.

Then last year, they got a call from The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. Another move, this time for even better positions. Mora is a professor in the Ohio State College of Medicine and associate director of lung research at the Dorothy M. Davis Heart and Lung Research Institute. Rojas is associate vice chair for research and a professor in the Department of Internal Medicine, in the Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine at the College of Medicine.

Recently, the two celebrated another year marking the day they met, as freshman, at a college orientation: Feb. 1, 1981. Every year they celebrate Feb. 1 along with March 18, the day they married in a colonial Catholic church in Bogota, where a violinist played Pachelbel’s “Canon” long before it was popular at weddings, and where friends and relatives came together after a party that had crept into the early morning with dancing and singing and friends serenading the couple.

At the time, they never imagined the life they started together would lead them out of the country of their birth, transplanting them to Nashville, to Atlanta, to Pittsburgh, to Columbus. They never imagined their work would be so intertwined, and that three decades after they began commuting together through Bogota traffic as medical school students in their early twenties, they’d still be commuting together, at the beginning and end of their every workday.