16 and healthy one minute, in dire need of a heart transplant the next

Healthy, athletic and only 16 years old, Ohio native Gigi was the last person you’d think would need a heart transplant. Until she collapsed at a family gathering, and a race against time began to save her life.

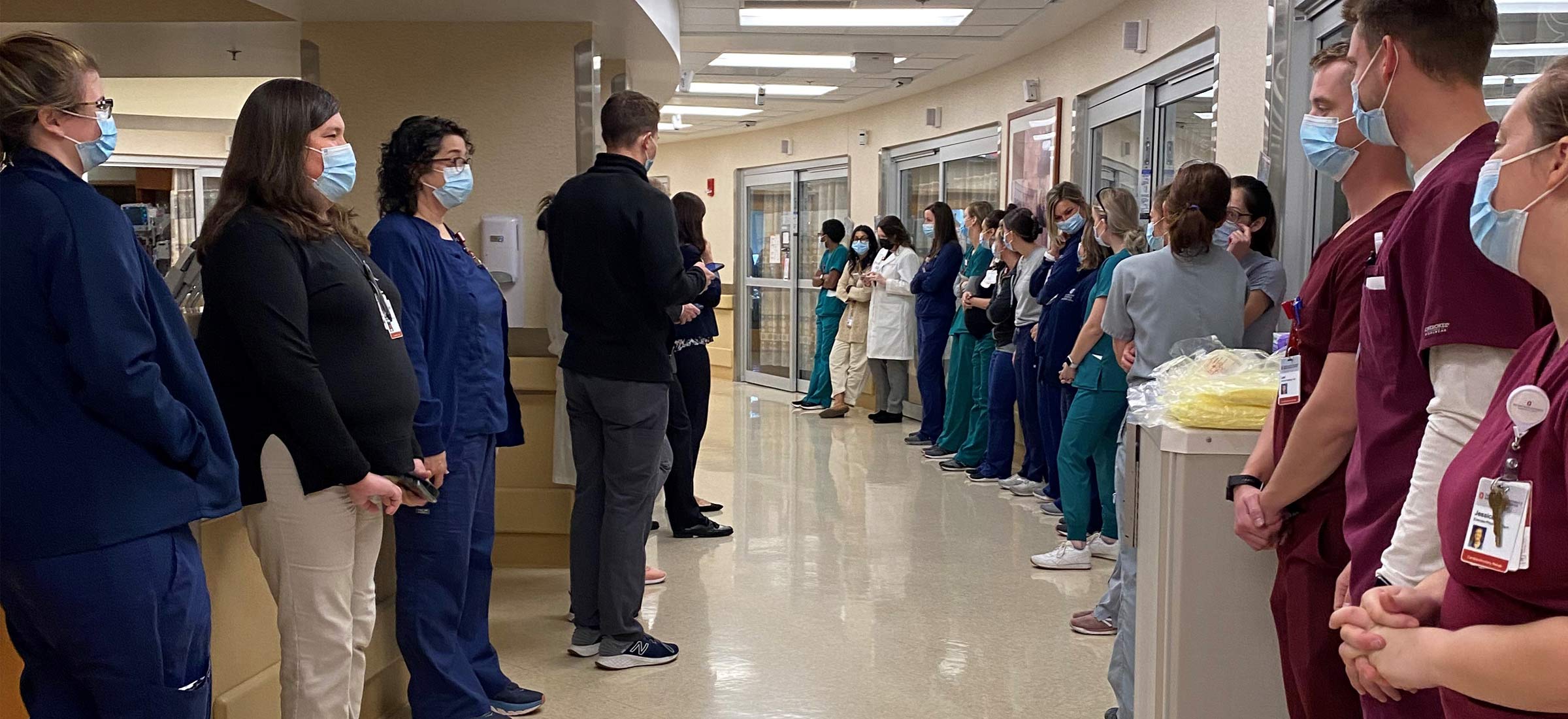

The scarlet and gray spokes of the pinwheel slowly spin as Janine “Gigi” Humeidan is wheeled down the hallway. Applause and cheers of “yay, Gigi” and “good luck” bounce off the walls of the Ohio State Richard M. Ross Heart Hospital.

Tears slip from the eyes of the nurses, physicians, therapists, nurse practitioners and social workers lined up along the sixth floor hallway, there to pay tribute to the petite teenage warrior who beat the odds and survived a potentially life-ending heart condition.

Clutched in Gigi’s left hand is the pinwheel, designating her as a transplant recipient.

As it spins, so do the memories of what it took to keep her alive and how her fighting spirit inspired the intensive care unit team at the Ohio State Ross Heart Hospital for weeks.

An undetected, rare genetic heart disorder had caused her heart to stop during a family gathering. Her aunt, an anesthesiologist at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, saved her life with chest compressions.

That cardiac arrest event in August was the start of a series of severe health problems that resulted in her flatlining more than a dozen times, being put on life support, having a temporary mechanical heart put in until a donor heart could be transplanted and — as a complication of her severe illness — eventually losing her right leg.

“When Gigi arrived on our doorstep, she was as sick of a patient as any of us at the Ross have ever seen. Our backs were up against the wall but our team came together with heroic support.”Nahush Mokadam, MD, the Gerard S. Kakos, MD, and Thomas E. Williams Jr., MD, PhD, professor in the Ohio State College of Medicine

Two floors below, Nahush Mokadam, MD, a cardiac surgeon at the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, steps out of the operating room and sees a text that Gigi is about to be discharged. He’s missed her celebratory send-off to rehab by just a few minutes. Shaking his head in disappointment, the cardiac surgeon muses about how he would’ve enjoyed experiencing that moment. Her case and care inspired the entire intensive care unit at the Ross Heart Hospital, including an Environmental Services worker who visited her each evening and even bought her an Ohio State blanket.

Gigi’s genetic heart disorder is so unusual that only a handful of cases have been documented in the world, and it’s even rarer that it wasn’t detected when she was younger.

“Gigi arrived just before Labor Day in 2021, and we were hitting our peak of patients with the delta variant of COVID-19. Our system was taxed to its limits. Nurses and providers were exhausted, and the hospital and ICU were full. She arrived in the midst of all this, and everybody pulled out all the stops to take care of this delightful young woman,” says Mokadam, who led her care.

From field hockey to heart transplant

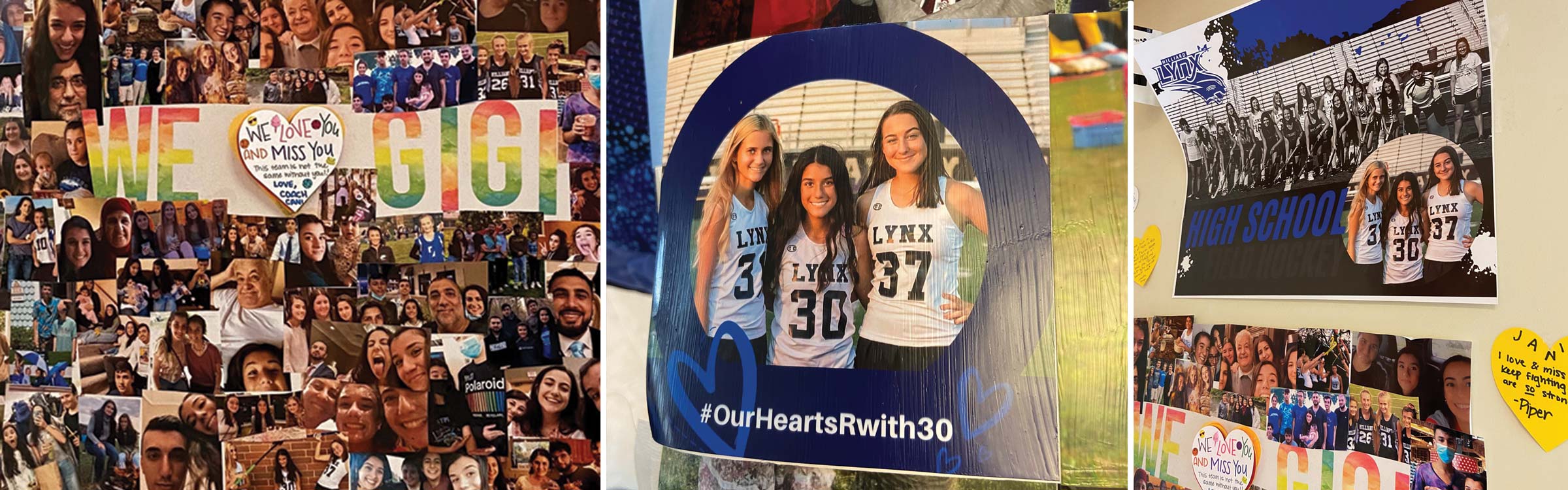

Sitting on a sofa that pulls out into a bed for overnight stays in the Ross Heart Hospital, Gigi’s parents Ed and Rola Humeidan reflect on Aug. 28, the day that changed their lives forever. On that hot, sunny Saturday, Gigi was running up and down the field with her Hilliard Lynx field hockey club teammates during a home game. The diminutive No. 30 played hard and nothing was amiss. After the game, Gigi wanted to hang out with friends, but plans were already in place for a family gathering at her grandmother’s house near the Columbus suburb of Westerville.

While playing with her cousins, Gigi suddenly went still on the couch. At first her family thought she was goofing around, but when she didn’t respond, everyone became alarmed. Gigi’s aunt, Michelle Humeidan, was upstairs with her oldest child when she heard her name being called urgently and repeatedly.

“The baby’s probably doing something cute that they want me to see,” she said to herself as she hurried down the stairs. Instead, a frantic scene was unfolding before her. Gigi was motionless on the floor of the living room. Michelle quickly took action, trying to figure out what was wrong. She checked her niece’s mouth to see if food was blocking her airway. Nothing. No signs of trauma or evidence of a seizure. Michelle checked for a pulse. Nothing. As Gigi started turning blue, Michelle’s medical training kicked in. She has both a medical degree and a postdoctoral degree from the University of Kentucky.

“Call 911,” she yelled while starting chest compressions. A mere 90 seconds later, the ambulance arrived and paramedics took over, using an automated external defibrillator to shock her heart.

“I could see (on the screen) that she was in ventricular fibrillation. I kept thinking ‘This is really happening. I can’t believe it.’ In the back of my mind I thought maybe I’d been overreacting, but I wasn’t. It was all so surreal. It was so unlikely for Gigi to have cardiac arrest,” says Michelle, a clinical associate professor of Anesthesiology in the Ohio State College of Medicine.

Paramedics were getting ready to intubate Gigi when she started breathing on her own. She was taken to Nationwide Children’s Hospital for testing. She was alert and starting to appear normal. At the hospital, her parents were told that she may need to spend the night for additional testing and observation.

“She was good for several hours, but then she had another cardiac arrest and everything went downhill from there. It was obvious something more ominous was going on,” says Michelle.

Over the next two days, Ed and Rola watched their daughter flatline 16 times in the intensive care unit. She was resuscitated by electrical shock over and over again until she was finally put on a form of life support called extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). The heart-lung machine is used for the most severely ill patients. “Every muscle and bone in my body ached with fear watching her,” says Rola.

But Gigi continued to have irregular heartbeats and her doctors couldn’t figure out what was wrong even after ruling out a bacterial or viral infection. She was going to need a heart transplant. The news shook Gigi’s family to the core.

“It was extremely difficult to make sense of it. She went from being a completely healthy 16-year-old kid playing field hockey to immediately needing a heart transplant, and we didn’t know why this happened. It was hard to accept,” says Michelle.

“I’ve got a pretty sick kid here”

About the same time doctors were deciding where to transfer Gigi for the highly specialized care she required, Mokadam learned about her case.

“I’ve got a pretty sick kid here,” a colleague who works at both Nationwide Children’s and the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center told him. As Mokadam listened to details of Gigi’s case, the cardiac surgeon, highly experienced with advanced heart failure and heart transplant, started advocating for her to be transferred to Ohio State, as did Michelle.

“She got really, really sick so quickly and I wanted her at Ohio State and close to home,” says Michelle.

As Gigi continued to struggle after arriving at Ohio State, Mokadam made the first of many hard decisions. Knowing she needed a heart transplant, he first needed to remove her heart and put in an artificial one to keep her alive while she waited.

Because she is just 4 feet 9 inches and 85 pounds, even the smallest total artificial heart was a bit too big for her chest. So to accommodate the artificial heart, Mokadam kept her chest open a couple of inches and used a sterile vacuum dressing to prevent infection during the wait for a heart transplant.

Meanwhile, doctors finally had an answer to what had caused her heart failure. In examining her heart, they discovered she had an extremely rare genetic defect.

A donor heart was located, but it was not of adequate quality for transplantation, devastating Gigi’s family. Time was running out. The treatments that were keeping Gigi alive had their own complications. Both ECMO and artificial hearts can cause loss of circulation in limbs and extremities. Indeed, Gigi’s toes had started turning black and surgeons had to amputate part of her right leg while waiting for a suitable heart. Two days after the amputation, another heart was identified that proved promising. But was Gigi strong enough to survive heart transplant surgery?

“All of these decisions were incredibly difficult for her family and our whole team to make,” says Dr. Mokadam.

“It was touch and go, day by day, minute by minute. It was incredibly demanding. But at the same time, she was a 16-year-old girl and had the vigor of youth and we believed her body might be able to withstand this.”

The heart transplant on Sept. 18 was successful. But Gigi still had a long way to go.

“I want to go home”

Exhausted by an influx of patients deathly ill with COVID-19 during the Labor Day holiday weekend — and a full suite of ECMO patients — physicians, nurses and other clinicians in the intensive care unit felt drawn to Gigi. She was their ray of hope. She would be the one to defy death and survive.

It was a victory the staff desperately needed after recently watching pregnant mothers and young patients die of COVID-19 despite their best efforts.

“The staff really rallied around her. Everyone recognized this was an extraordinary situation,” says Brea McLaughlin, advanced practice manager of the Ross Heart Hospital’s surgical services.

Two of those nurses were Anna Wells and Kelly Coakley, who worked in the cardiothoracic transplant unit. They helped comfort and calm Gigi when she woke up to discover her right leg was gone. They did “spa days,” washing and braiding her hair and watching and laughing at teen movies like “Mean Girls.”

Her aunt, Michelle, read her Harry Potter books, and a poster of her field hockey team and snapshots of friends were displayed around her hospital room.

At Halloween, when Gigi was stronger, Brea put her in a recliner and wheeled her outside to see friends and family. When she couldn’t talk, a nurse communicated with her by sign language, which Gigi had learned in high school. The teen kept signing the same thing over and over again, tugging at everyone’s hearts: “I want to go home.”

“She was the light in the middle of so much darkness; you could see her brightness and determination shine through and we really needed that,” says Kelly, as Anna finished her thought. “She came in here strong and athletic and with a lot of spunk. We knew if she could get through this, she could survive anything.”

When Gigi’s spirit was especially low, Thomas Ryan, MD, director of the Ohio State Heart and Vascular Center and the John G. and Jeanne Bonnet McCoy Chair in Cardiovascular Medicine, reached out to former patient Blake Haxton, who was treated at Ohio State after losing both his legs as a high school senior to necrotizing fasciitis, commonly known as “flesh-eating disease.”

When Gigi’s spirit was especially low, Thomas Ryan, MD, director of the Ohio State Heart and Vascular Center and the John G. and Jeanne Bonnet McCoy Chair in Cardiovascular Medicine, reached out to former patient Blake Haxton, who was treated at Ohio State after losing both his legs as a high school senior to necrotizing fasciitis, commonly known as “flesh-eating disease.”

Blake Haxton, who won a silver medal in paracanoeing at the 2020 Paralympics, visited Gigi in her hospital room. She listened carefully to his story and words of advice.

“He said, ‘If the prosthetic doesn’t matter, you can do regular things,’” Gigi said in a soft voice still raspy from being intubated. It gave her hope that she could play her beloved field hockey again someday.

“I hope she can take this experience and run with it for the rest of her life. What could stop her now? She can do anything, be anything,” Michelle says of her niece.

“When you go into medicine, there’s a lot of sacrifices and things you miss along the way. I can honestly say that everything I’ve ever sacrificed was worth it for those 2 minutes I spent saving Gigi. I would do it all over again.”

A heartfelt thank you

Handing her crutches to her mother, Gigi walks gingerly but confidently down a hallway of the Ross Heart Hospital on Jan. 31. It’s been nearly three months since she was transferred back to Nationwide Children’s Hospital for inpatient physical and occupational rehabilitation. She was fitted with a prosthetic leg there and a few days before her 17th birthday at the end of December, she returned home. About two dozen cars filled with family and friends paraded past her house in Hilliard, wishing her happy birthday and welcoming her back home.

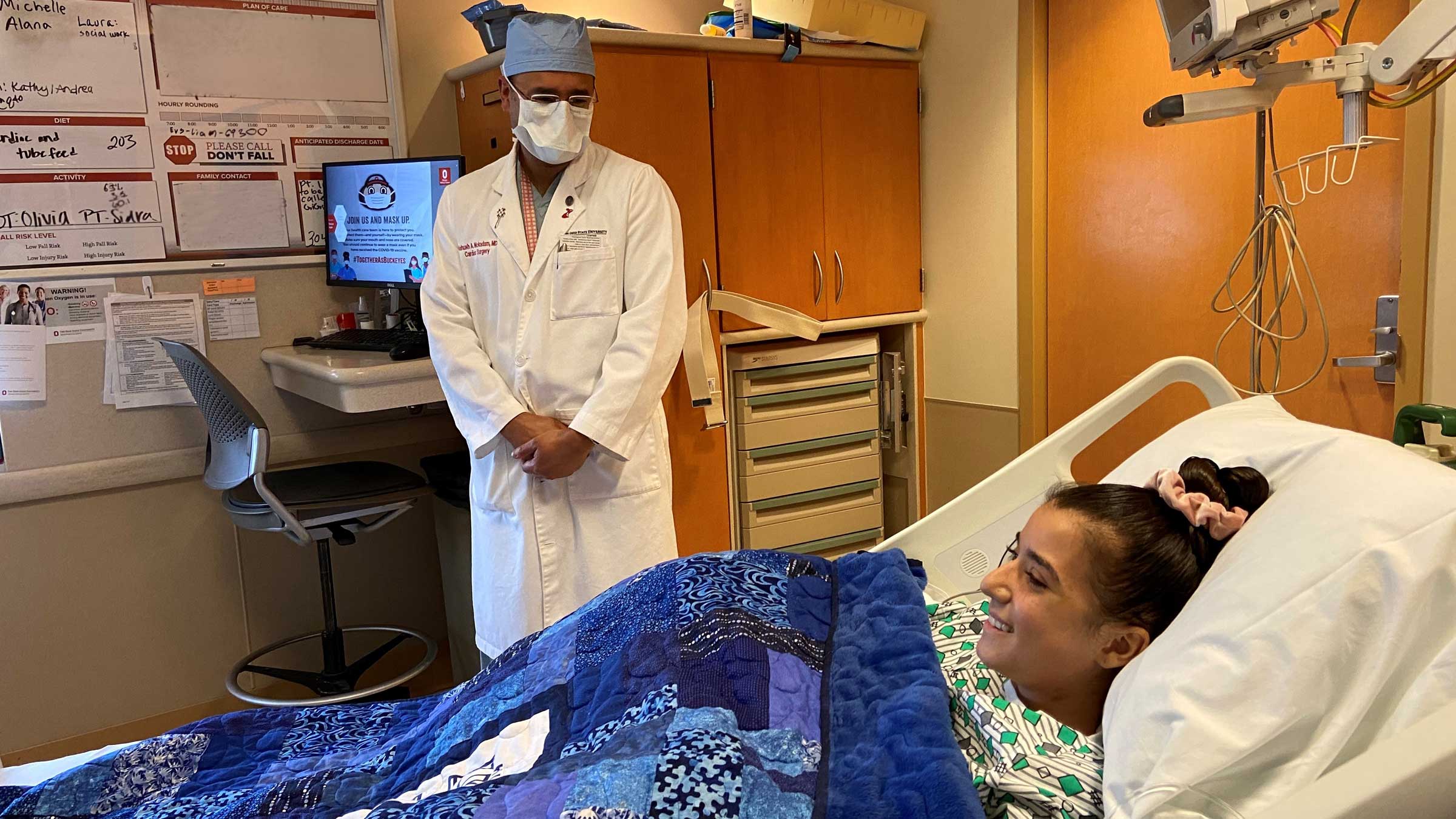

Now she’s back at the Ross Heart Hospital, which her parents describe as her other home. It’s time for her first in-person checkup with Mokadam since she was discharged. Gigi and her parents light up when he enters the exam room.

“Wow, you look great,” he says. At his urging, the quiet teen shares stories about improving her walking, returning to school two days a week and dreaming of one day playing field hockey again. Mom Rola pipes up, describing how Gigi’s becoming more and more independent and recently did a photo shoot with friends showing off her prosthetic leg.

“We can’t thank you enough. Just seeing how she is now is a miracle,” Rola says as Mokadam quickly chimes in that “it took a village” to save her life. Dad Ed pauses as he flashes back to the dark weeks when Gigi was touch and go. It’s still raw and traumatic for the couple and their other children, Manar, 22, Emily, 21, and Laith, 15. Slowly, they’ve been filling in the many gaps for Gigi.

“All the staff was amazing. They gave us hope every day. We couldn’t see the outcome, but they could,” Ed says softly. The room grows quiet as Gigi reaches into a bag and pulls out a colorful heart-shaped card she made.

The words on the card strike a chord with the surgeon and Gigi’s parents: Thank you so much for all you’ve done for me to keep doing the things I love with the people I love. I will never forget the impact you made on my life.

Touched, Mokadam pulls Gigi into a heartfelt hug.

“Keep up the spirit,” he tells her. “Believe me, we didn’t think you were going to be here today. It was quite an ordeal. And yet here you are and we’re all thrilled.”

When it comes to your heart, choose the best

Ohio State’s Richard M. Ross Heart Hospital has been named central Ohio’s best heart hospital by U.S. News & World Report. Trust your heart care to the experts, with convenient outpatient locations throughout central Ohio.

Learn more