How much is relative? Heart study provides genetic insight into deadly dilated cardiomyopathy

Sharon Starks was only 26 years old when she first started showing signs of heart failure. She was waking up at night with shortness of breath and sounding like she was gurgling water. She knew something wasn’t right and was stunned to learn that she had dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), a condition in which the heart muscle weakens and the left ventricle enlarges. It’s the most common cause of patients needing a heart transplant and estimated that 1 in 250 Americans have DCM.

Now results of a multi-site study led by researchers at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center are providing insight into this deadly disease that is of particular interest to Black patients like Starks who lives in a Dayton suburb. Researchers believe most idiopathic (cause unknown) DCM has a genetic basis. Starks can see a family connection — her grandmother died at age 29, and her mother had double heart bypass surgery at age 44.

“I ended up in the hospital and coded a couple of times. It can be a silent killer and is so scary,” Starks said.

Researchers studied the prevalence and risk of familial DCM in Black and white patients and their family members, noting most studies have included only whites even though Blacks with DCM have a higher risk of heart failure-related hospitalization and death.

Using mathematical modeling techniques, researchers estimated that 30% of patients with DCM had at least one first-degree family member (child, sibling or parent) with DCM. When broken down by self-identified race, an estimated 39% of Black patients and 28% of white patients had at least one first-degree family member with DCM. The five-year study enrolled 1,220 patients with DCM, of which 44% were women, 43% were Black and 8% were Hispanic, along with 1,693 of their first-degree relatives.

“Our study shows that families of Black patients are at greater risk for DCM than those of white patients. We don’t yet understand all of the reasons for this. It could be from differences in genetics, comorbidities or social determinants of health. This analysis, which only included clinical information, was unable to clarify that.”Dr. Ray Hershberger, a cardiologist and division director of human genetics at the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center and a researcher at the Dorothy M. Davis Heart and Lung Research Institute.

Hershberger, who holds The Charles Austin Doan Chair of Medicine Funded by the Charles Austin Doan Fund at The College of Medicine, is senior author of the study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association. He heads up the DCM Consortium, which is composed of 25 leading academic U.S. heart failure/heart transplant programs that contributed to the study.

DCM can occur in family members at almost any age but the typical onset is mid-40s. The severity of the condition can vary within families, with some family members exhibiting minor symptoms while others may die of heart failure or an arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat) causing sudden cardiac death. Symptoms include shortness of breath with exertion, fatigue, edema of the legs and feet, an irregular heartbeat or lethal arrhythmias.

The study estimated that about 1 in 5 first-degree family members of patients with idiopathic DCM were at risk of getting it during their lifetime.

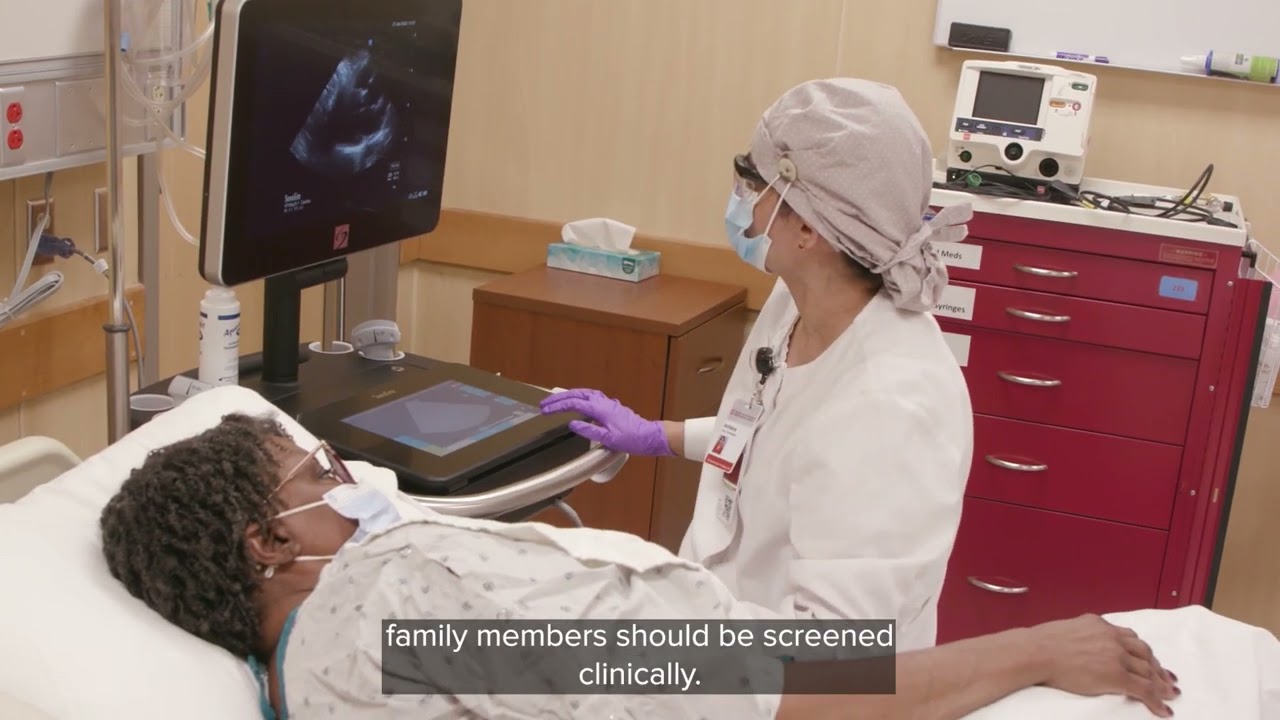

“DCM can be silent for months to years before symptoms begin. Eventually heart failure may develop, which is late-phase disease. Guidelines have recommended that, with a diagnosis of DCM, the patient’s first-degree family members undergo clinical screening including an echocardiogram so early asymptomatic DCM can be found and treatment initiated before progression to late-phase disease,” Hershberger said. “For the first time, this study gives us hard numbers on how to counsel family members on their risk of developing DCM and especially so for family members of Black patients with DCM.”

In 2014, Greg Ruf of Dublin was diagnosed with DCM and has been raising awareness since then about the disease that led to him having a heart transplant at Ohio State’s Richard M. Ross Heart Hospital. Nine family members have been identified with gene mutations known to cause DCM.

“There’s a million plus people in the United States that are dealing with this and unfortunately many don’t know. It's really important to prevent death in your family or advanced disease by getting tested and dealing with this thing head on,” the 57-year-old said.

That’s exactly what Starks plans to do with her 8-year-old son when he’s a bit older.

“My son will definitely be screened, and I’ve been educating my siblings,” Starks said. “Sometimes as a family we don’t tell each other what’s going on. Families definitely need to have more conversations, especially if there’s a family history of heart disease.”

Think you or your family might be at risk?

Start by talking to your primary care physician or contact the cardiology team at The Ohio State Heart and Vascular Center

Expert care starts here