Drawing his way to clarity after a bipolar disorder diagnosis

Going public with mental health disease inspires acceptance and creativity for Ohio artist

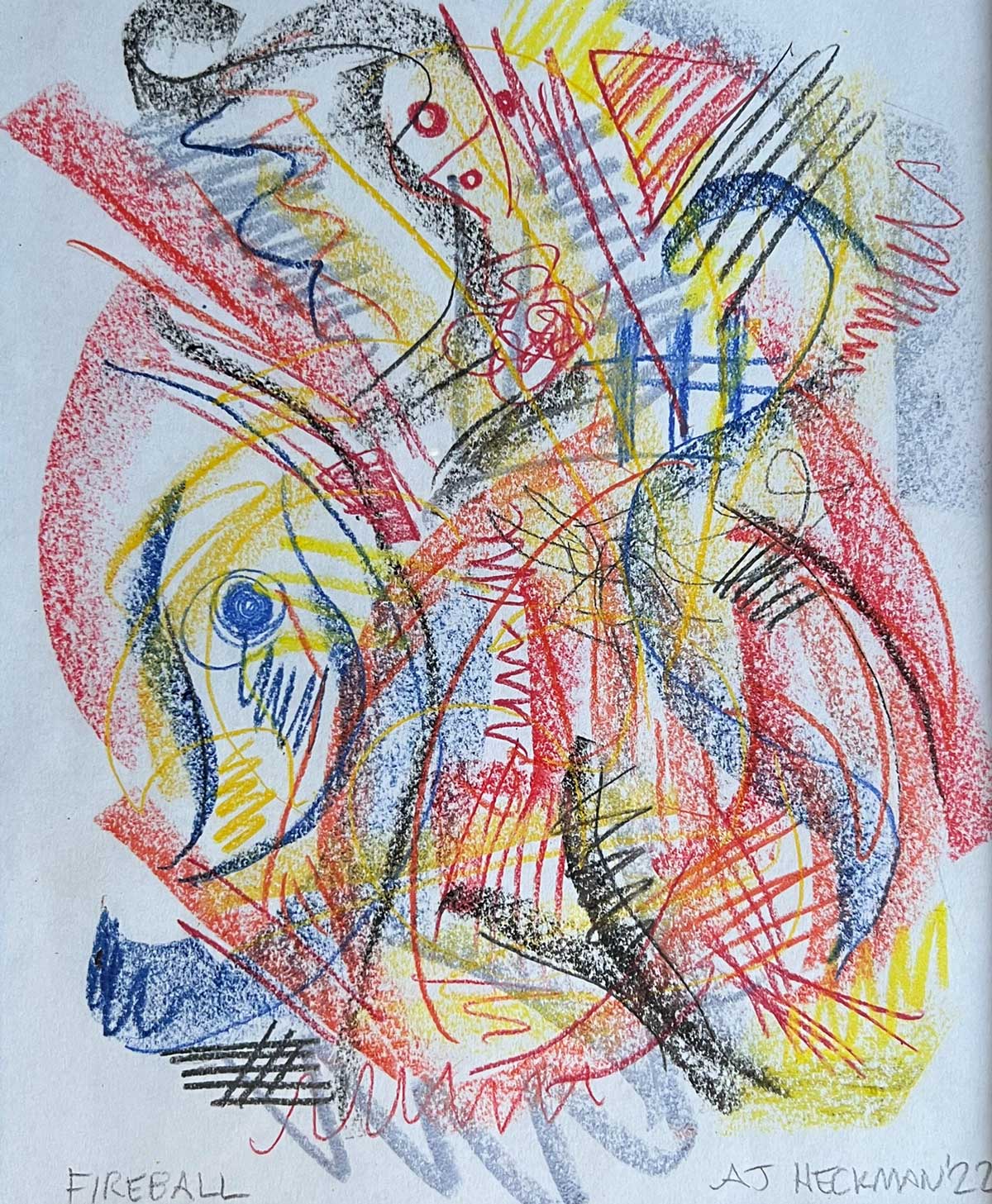

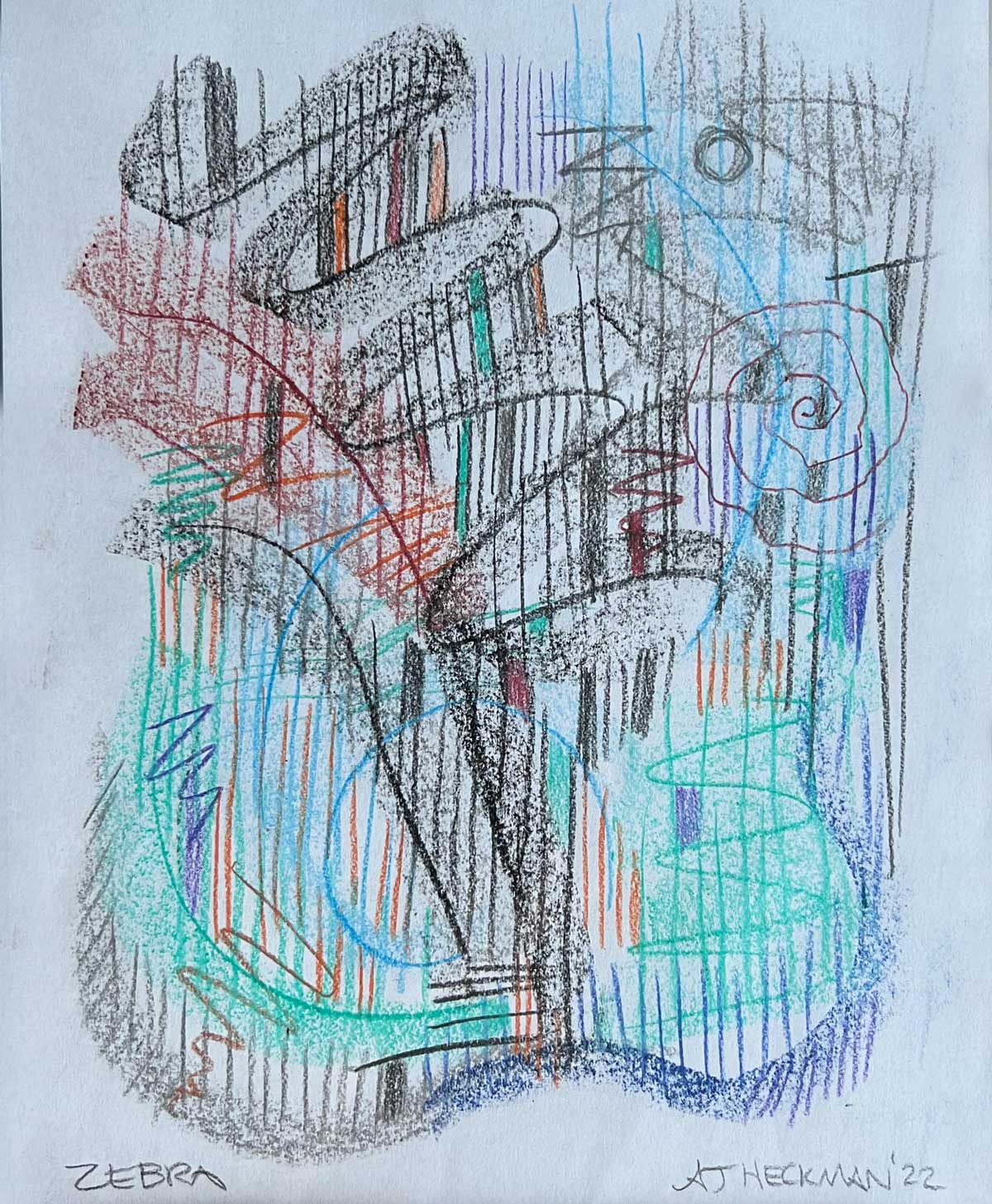

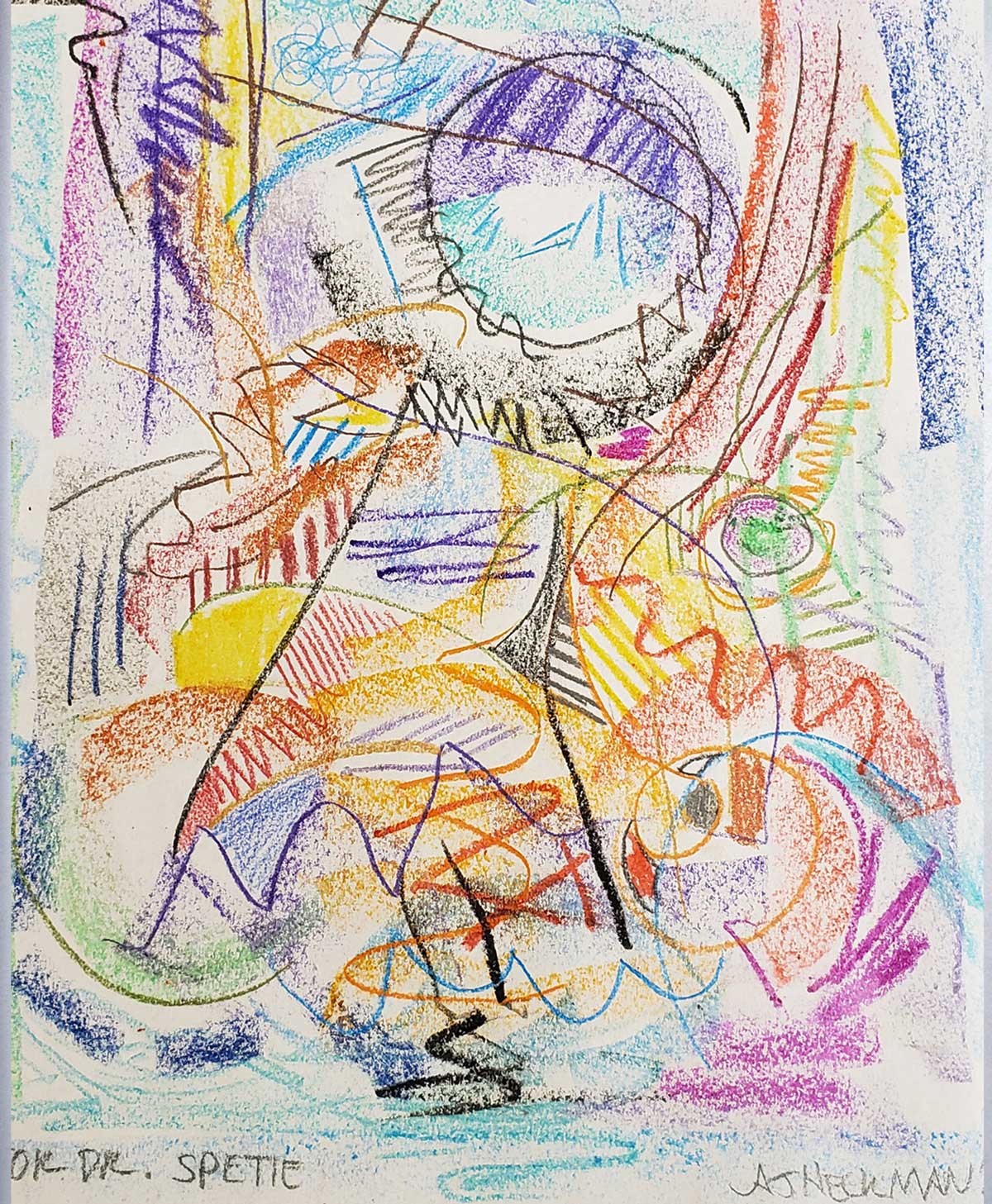

A cluster of lines — some straight, some curving — shades of red, purple, blue and slices of black all come together. AJ Heckman titled his drawing “Mania.”

For weeks, he had tried to explain to his wife, to his friends and co-workers, what he was thinking. What came out was a torrent of words, uttered so fast few could understand him or connect the ideas.

Lost in mania for the first time, Heckman’s thoughts swung from being so grateful for playing on the floor with his 5-year-old daughter, to imagining her moving out, leaving him; to his friend dying of leukemia two decades earlier; to his own cancer diagnosis 10 years ago; to a renewed connection he felt with God, with humanity; to his childhood neighborhood where he could see himself standing in the street calling 911 after his father had just collapsed from an irregular heartbeat; to intense satisfaction for being so productive — painting and reading, fueled on adrenaline and rock music, one day folding into the next with just a couple of hours of sleep.

Lost in mania for the first time, Heckman’s thoughts swung from being so grateful for playing on the floor with his 5-year-old daughter, to imagining her moving out, leaving him; to his friend dying of leukemia two decades earlier; to his own cancer diagnosis 10 years ago; to a renewed connection he felt with God, with humanity; to his childhood neighborhood where he could see himself standing in the street calling 911 after his father had just collapsed from an irregular heartbeat; to intense satisfaction for being so productive — painting and reading, fueled on adrenaline and rock music, one day folding into the next with just a couple of hours of sleep.

Then he began feeling lightheaded. He could no longer help take care of his two children. He needed to be hospitalized, his wife told him, which is exactly what a co-worker had urged a day earlier.

Willingly, Heckman went with his two older brothers to The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center Harding Hospital, a psychiatric hospital that offers emergency stabilization and inpatient treatment for patients like Heckman.

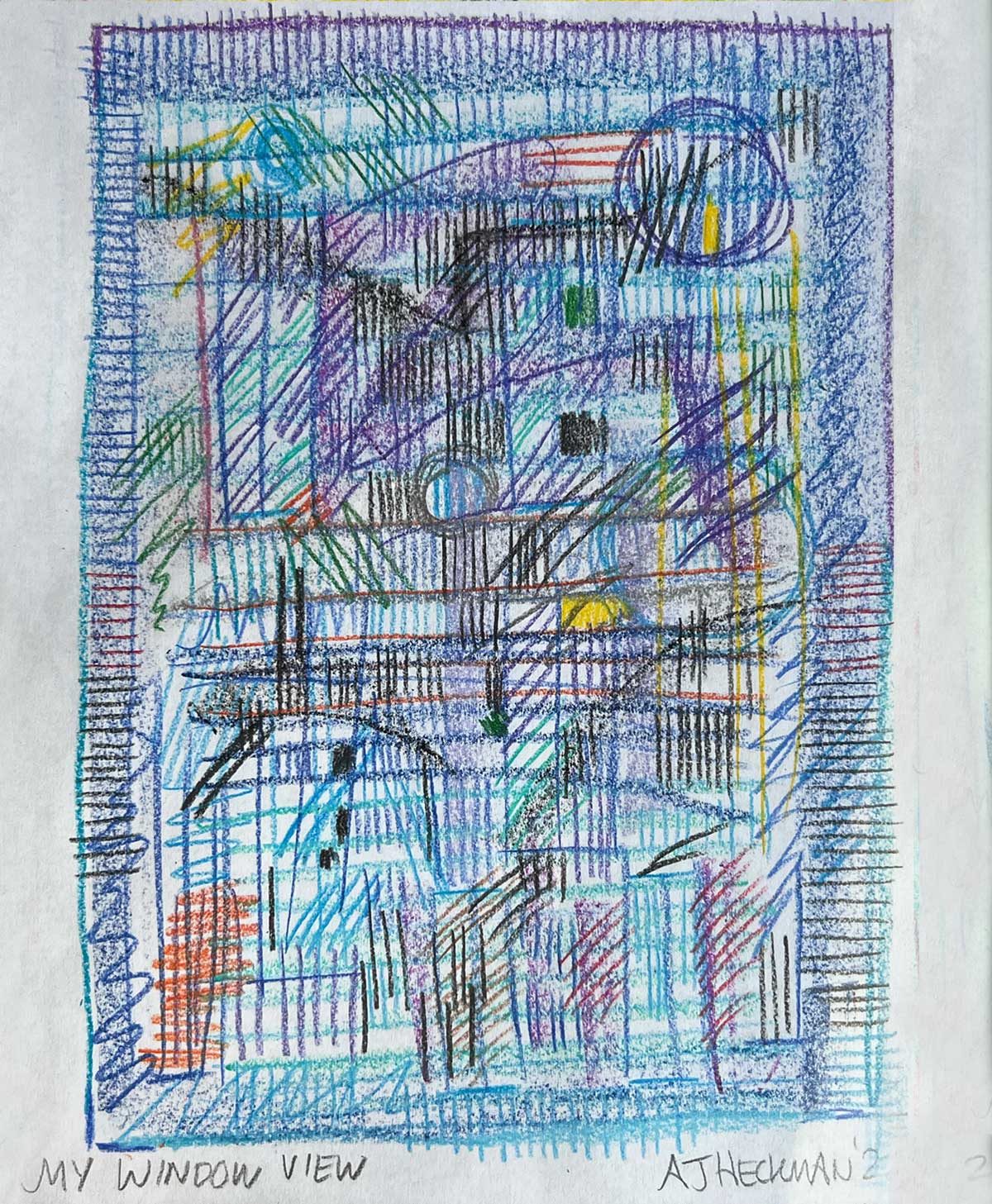

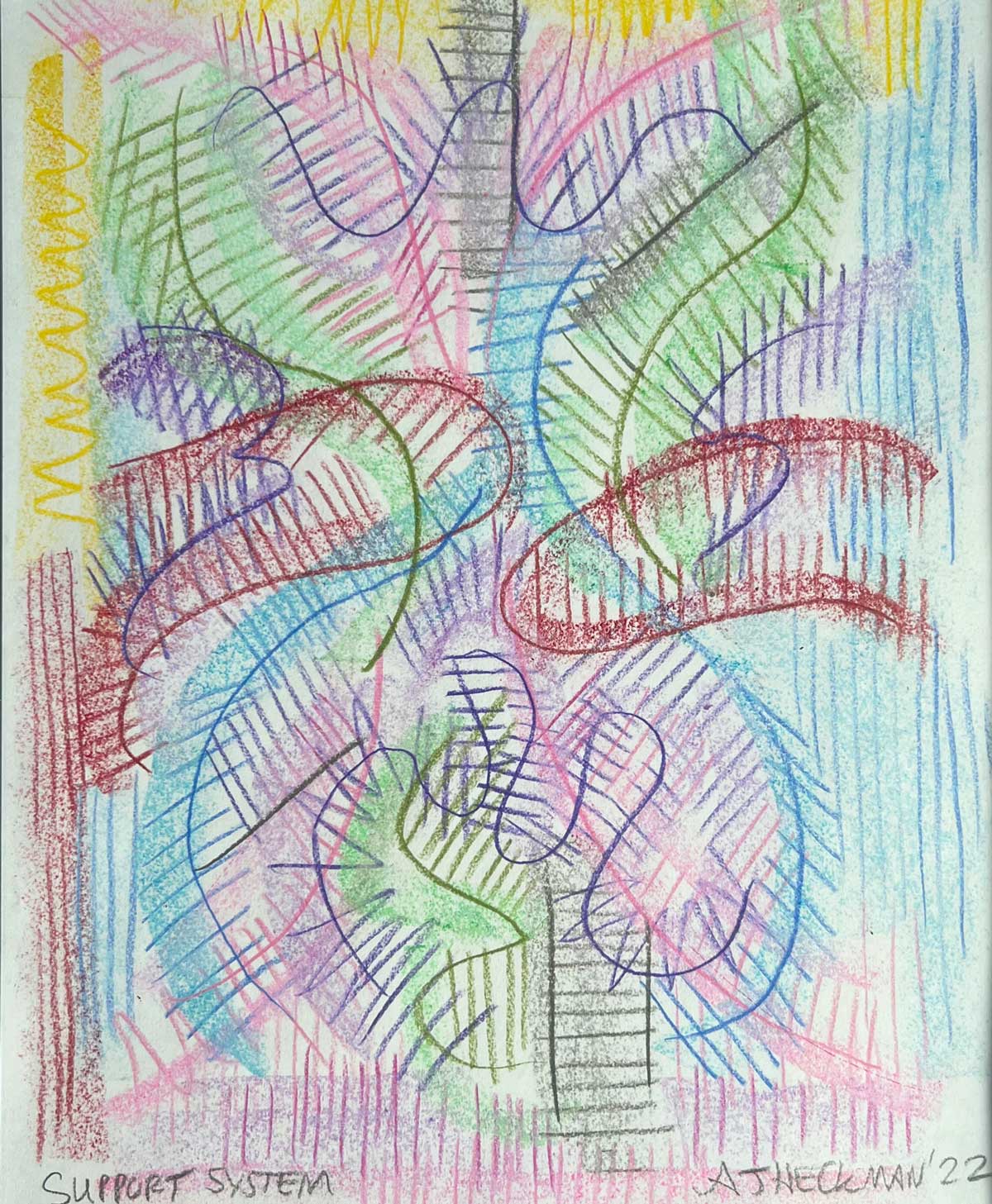

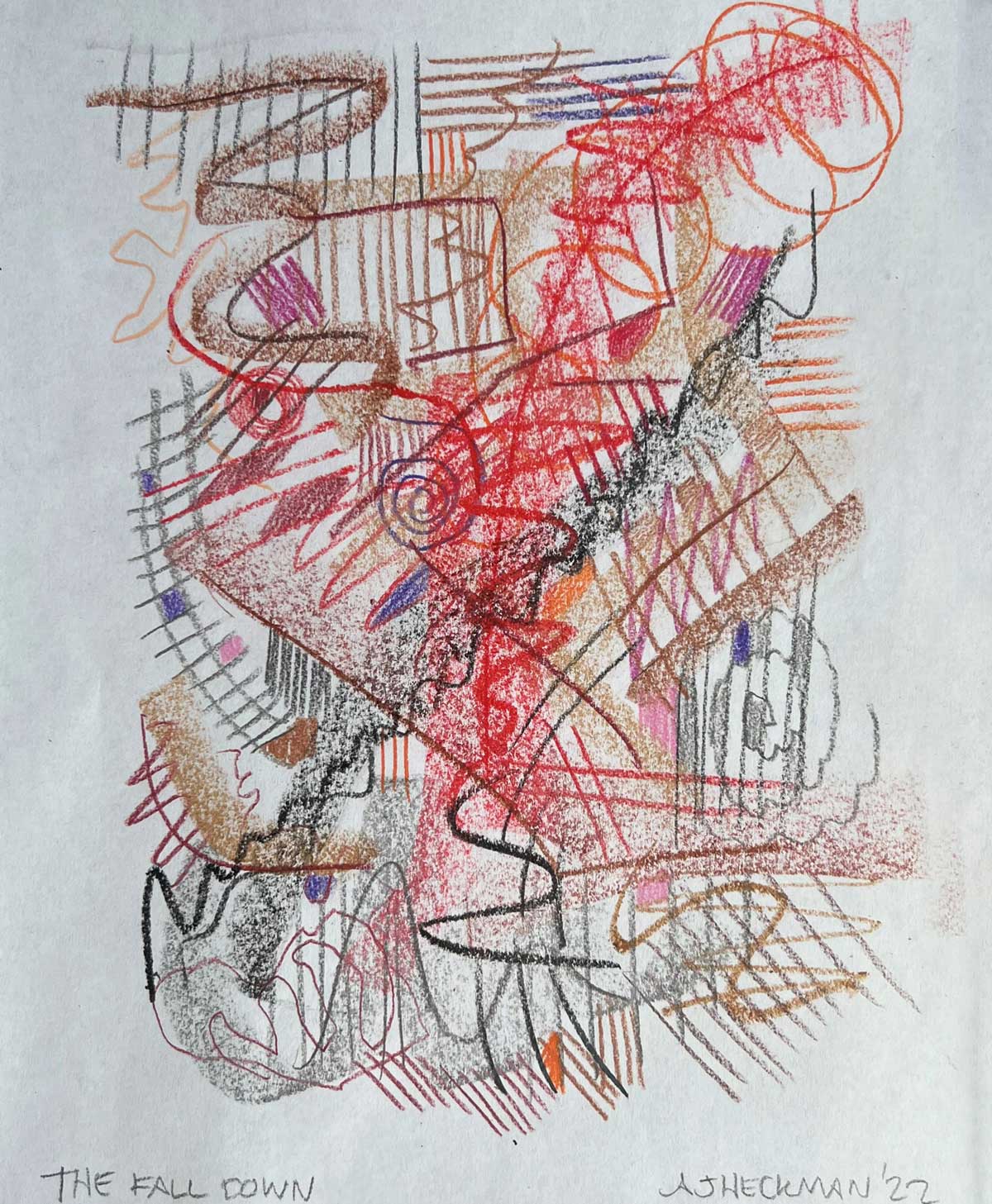

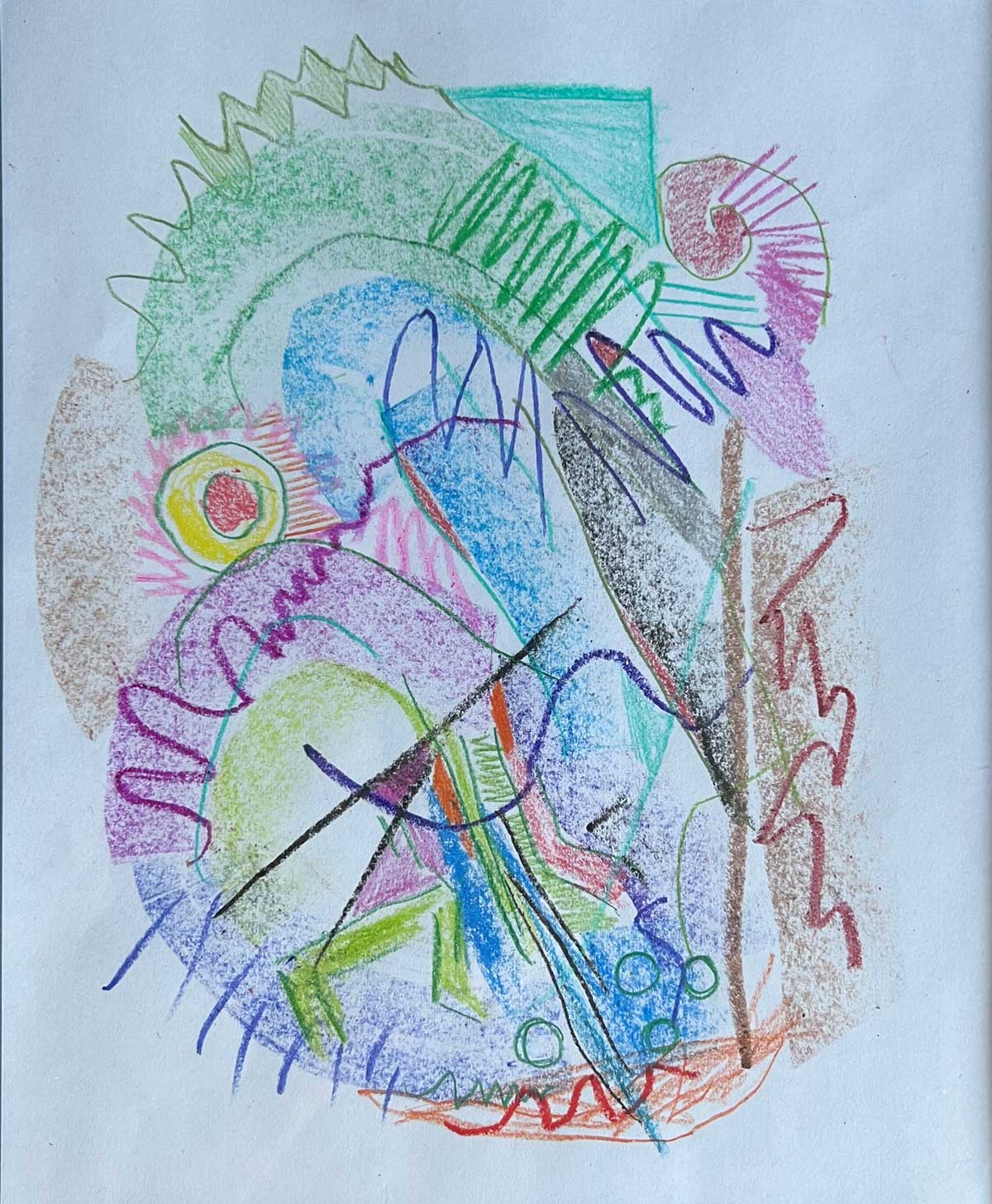

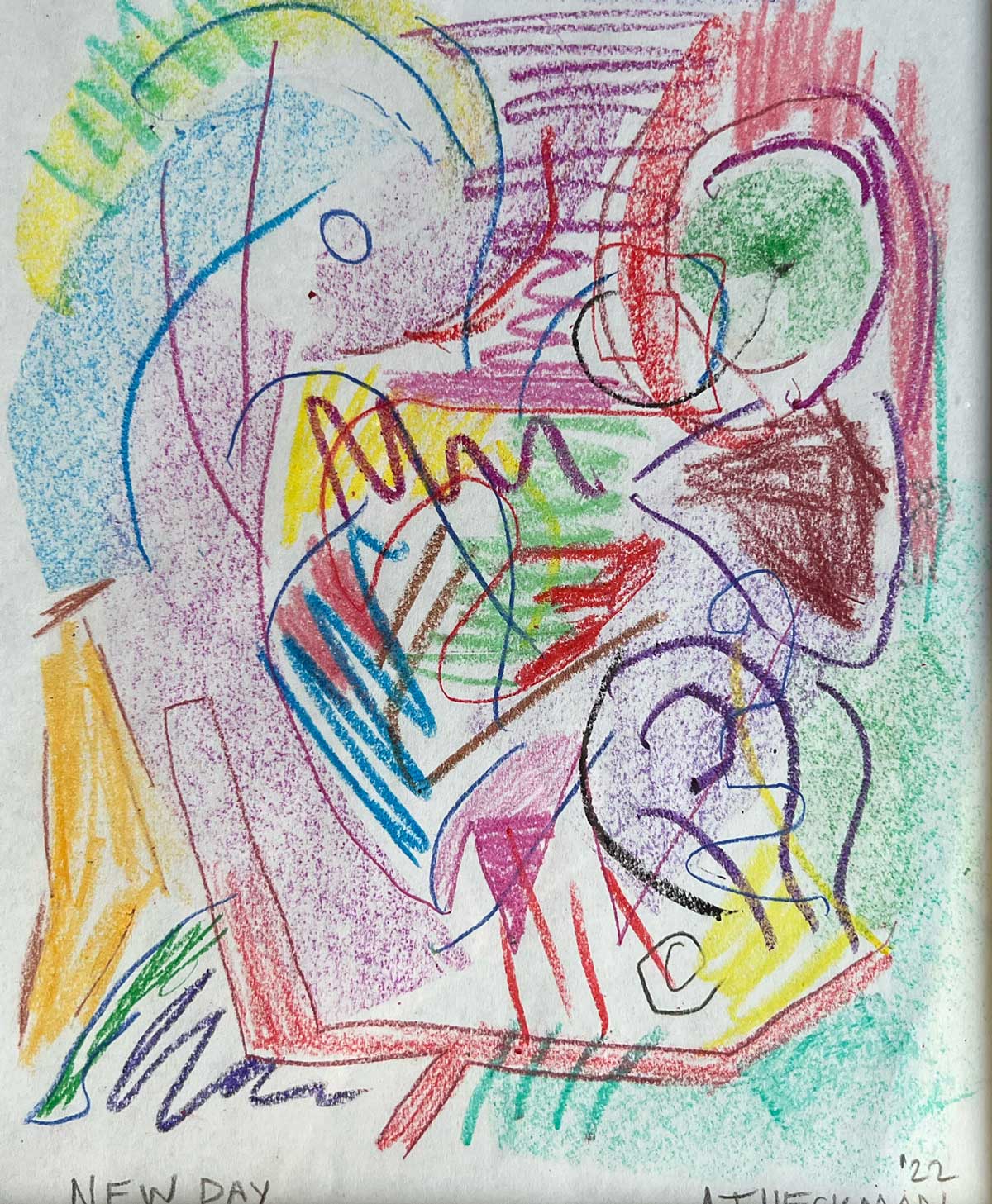

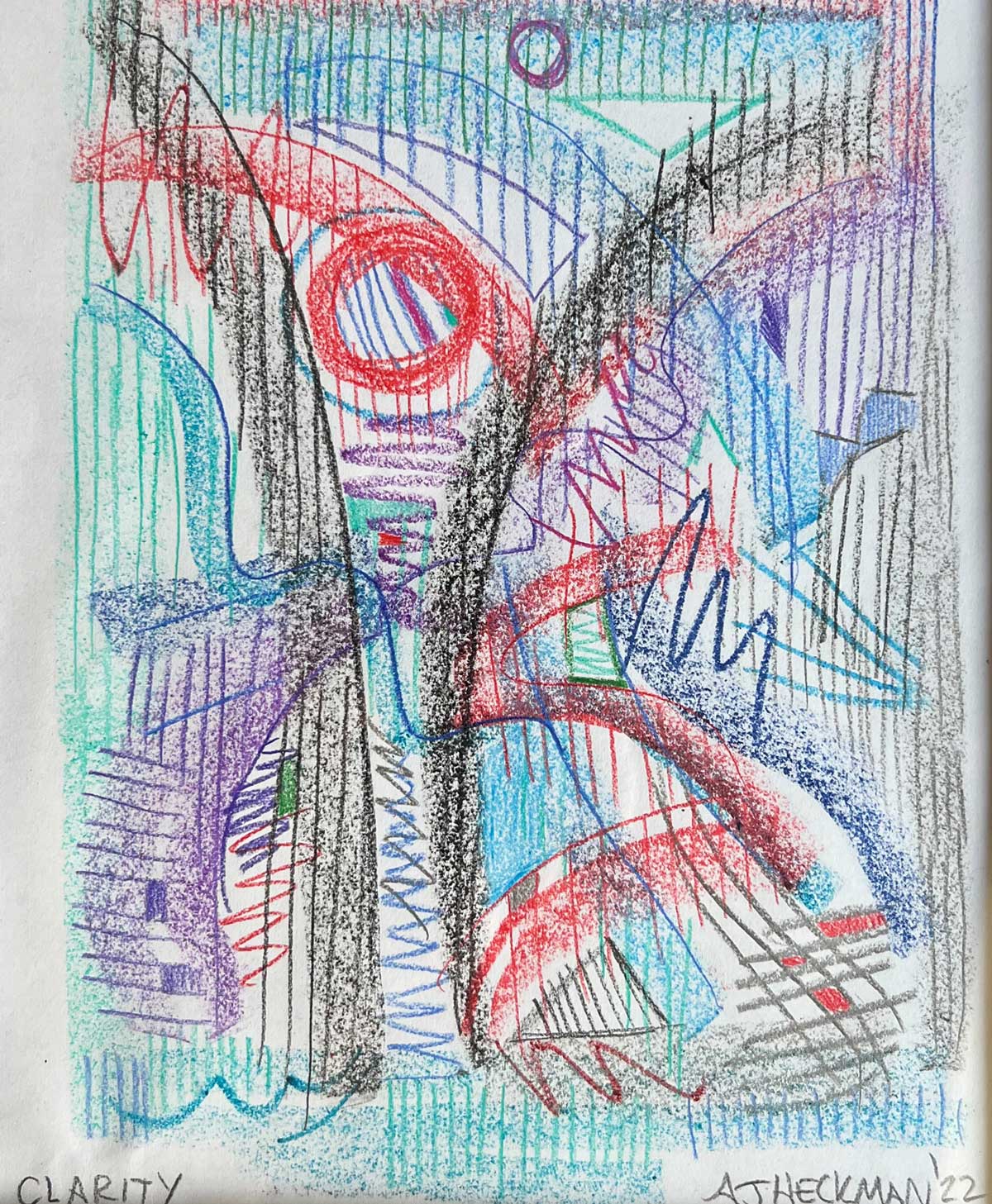

There he asked for paper and colored pencils. And then he drew, each picture like a prayer, he says, getting him through.

A couple of months later, Heckman sits in his family room beside a large plastic storage bin of framed pictures that together tell a story of one week in February.

“This one’s important.” He points to a drawing he titled “Bi-polarity.” He created it from the desk of his hospital room the afternoon he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and started on medication.

“It’s beautiful, but it’s chaos,” he says. “It was hard to pin down a thought. My thoughts were like liquid.”

A second picture Heckman gave the same title: “Bi-polarity.” This one he created after a few days of regular sleep, three meals a day and a mood-stabilizing daily medication.

“The first one, I layered on a bunch of stuff,” says Heckman, 38, explaining the difference between the two “Bi-polarity” pictures.

The lines in the second drawing are more definite, the space more organized.

“For this one, I knew when to stop.”

Unraveling his mind through artwork

An art and music preschool teacher for children with special needs, Heckman did what came naturally to him to untangle his thoughts: He drew. Many of the drawings he did in the hospital, an estimated 100 or so, he gave away to other patients, doctors, nurses, staff who manned the front desk, anyone he wanted to thank, anyone who answered the question: What’s your favorite color?

“If they said, ‘I don’t know,’ I’d ask, ‘What’s your favorite season?’” Knowing that would be enough to figure out a color scheme.

“I just got on a kick. Anybody who was nice to me, I drew them a picture.”

What else could he do to express how grateful he felt for having his mind slowed down, his thoughts clear? Feelings of wanting to end his life that kept coming up for him toward the end of 2021, that kept offering him a sense of relief, were finally erased.

As his mind clears, his drawings evolve

“AJ was drawing the whole time he was in the hospital,” says Emily Chase, MD, a psychiatric resident who treated Heckman.

“I’ve never seen a patient draw artwork like that and see it change as they were in the hospital. It was almost like validation the treatment was working.”

The extreme mood swings Heckman had experienced, typical bipolar disorder symptoms, were going away. The highs that made him feel boundless energy and made his mind and words race, the lows that made him consider ending his life.

Also known as manic depression, there are two types of bipolar disorder: bipolar 1 disorder, which Heckman was diagnosed with, and bipolar 2 disorder. With bipolar 1 disorder, the peaks are higher and include at least one episode of mania, a sustained period of unusually high energy and euphoria that keeps you from functioning. The hypomania with bipolar 2 is slightly less intense and less impairing, Dr. Chase says.

People with either bipolar 1 or 2 disorder are treated with a mood-stabilizing medication and with an anti-psychotic medicine if they’re experiencing psychosis, a disconnect from reality, she says.

“People may see or hear things that may not be there or feel like they’re talking to God and God is talking to them,” Dr. Chase says. “That can happen when someone is manic or depressed.”

A little more than half of the patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder respond to a mood-stabilizing medication, often lithium, and within a few days, the most impairing symptoms go away, says Lacramioara Spetie, MD, a psychiatrist and member of the team who treated Heckman.

“It really can go that fast,” Dr. Spetie says. “The improvement may continue over another two to three weeks.”

When Heckman started on medication, he feared his creativity would be crushed, that he would either stop drawing or his drawings would lack pizzazz. The opposite happened.

“It’s made my creativity better,” he says. “It made me think clearly. I’m more able to tap into what I was feeling and thinking. I’ve become more spontaneous and willing to open up.”

All the while, the social workers and psychiatrists who worked with Heckman took notice of the daily changes in both his mood and his artwork.

“The drawings started out more abstract, the lines were a little more uncertain,” Dr. Chase says. “As he progressed, the lines became a lot more defined.”

Among his first drawings in the hospital is something he had envisioned while still manic. Intersecting and multicolored upside-down curves represent spirits that ultimately come together at the peak of a mountaintop. At the time, he felt a deep connection with all of humanity, that though we all live in separate spheres, we become one.

An ode to the medications

His collection includes a picture titled “Lithium” and another “The 'Quel,” short for Seroquel. Both medications he credits with giving him a calmer, clearer mind, adding guardrails on a winding highway with sheer drop-offs.

The medication as well as the group and individual therapy Heckman received during hospitalization and since have made him feel even better than he felt before the manic episode that led him to the hospital, he says. For much of his life, he had lived in his head, rehearsing everything before it happened, second-guessing himself afterward.

He was more irritable, less patient. Now he’s open, less self-conscious.

“A lot of it has to do with the willingness of the patient,” says Robin Trevas, a social worker who was part of Heckman’s care team.

“Sometimes patients are reluctant for us to give them the care they need. That’s half the challenge, ” Trevas says.

Finding the right medication or balance of medications can take days, maybe even weeks for some patients, or it can happen quickly as it did for Heckman, within a week.

Before Heckman left Ohio State Harding Hospital, Trevas and other social workers did what they do for all patients to help with the transition. With Heckman’s permission, staff linked him to outside counseling and medication management, identified a supportive network of friends and family members and ensured he had a safe plan if he found himself in a crisis. They also helped him set a goal to stay on track with medication and therapy, regular sleep, meals and exercise.

During a mental health crisis and for six months afterward, a patient needs an intensive treatment plan with mental health professionals, Dr. Spetie says.

“That takes a commitment on the patient's part and on the families’ part,” she says. “Depending on the patient's understanding and willingness to make that commitment, the treatment will be very effective, somewhat effective or it will lose its effectiveness, and oftentimes people will experience a relapse.”

The main intent for anyone hospitalized at Ohio State Harding Hospital is to stabilize them so they’re no longer a threat to themselves or others and can function outside the hospital. On average, patients stay five to seven days. Therapy is provided every day in groups and one-on-one, but instead of delving deep into a person’s trauma or other issues, the focus is on getting people back to regular patterns for their daily activities, along with finding the right type and dose of medication.

“I tell patients that people on a cardiac unit have to take medication for their hearts,” Trevas says. “The brain is an organ, too. You have to take medication to make it function properly. Embrace that. Your life can be very, very good.”

Heckman has discovered that. In the days after leaving the hospital, he had a decision to make. He had sold his paintings online for years, and he had an exhibition coming up at the Bexley Public Library. Did he want to announce that he’d been diagnosed with bipolar disorder and had been hospitalized? It would be a risk, for sure. He could keep it to himself without anyone besides his family and friends knowing.

But he was ready to open up. He figured it just might inspire someone else who struggled with some type of mental illness to feel less alone or seek help or just be able to talk about their diagnosis without feeling like an outcast.

Going public with a mental health diagnosis

So, he posted about it on a website linking local artists with prospective buyers. The response was immediate. People emailed, congratulating his bravery, offering empathy. They, too, had a mental illness or a family member with one. They, too, could relate to the dips and peaks and mental exhaustion.

In a display case in the Bexley Public Library, Heckman’s drawings were presented in a collection he titled: “CLARIFIED MANIA: Living and Creating with Bipolar Disorder.” At the opening, people congratulated him not just for the work but for his bravery in revealing he had bipolar disorder.

On a recent sunny day, Heckman stood on his front porch, brimming with appreciation for the support of his wife, 3-year-old son and 5-year-old daughter, for all of his family members, for the entire team of staff members in the hospital who encouraged and challenged him and for the wise co-worker who had nudged him: “Dude, you need to get help.”

At times, Heckman wakes up in the morning feeling groggy, with a mild headache, possibly side effects from the medication. Still, he’s glad to be sleeping again.

“I have a psychiatrist and a counselor,” he says within earshot of a neighbor walking to his car. “And I’m good with that.”

Artwork created by AJ Heckman during his inpatient stay at Ohio State Harding Hospital

Help for mental health conditions

Ohio State offers personalized, compassionate care for your mental health concerns.

Learn more