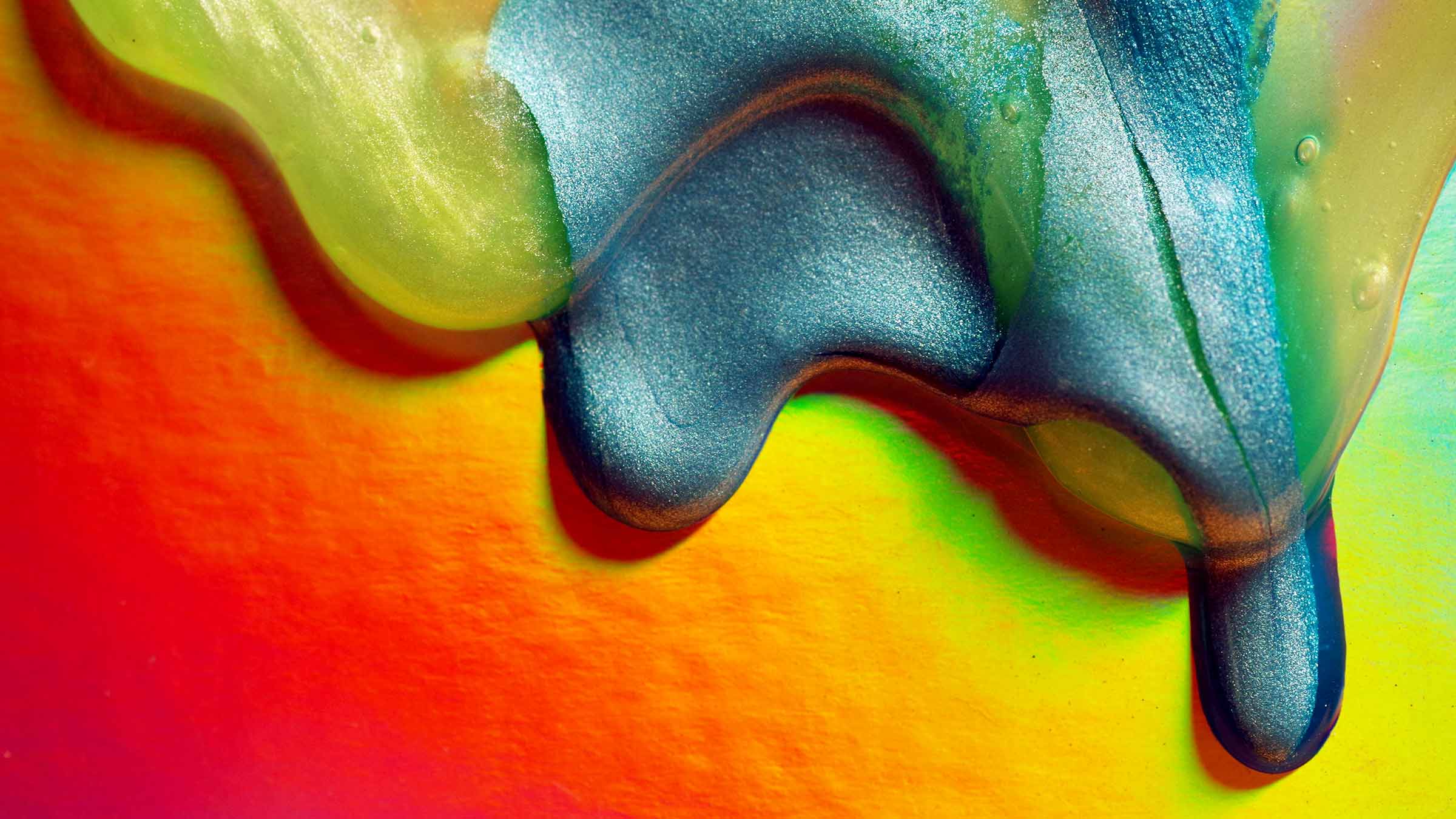

Snot, mucus, sputum, phlegm — it goes by many names, but does that often-colorful fluid that oozes from your body really have a purpose?

By definition, phlegm is a byproduct of inflammation in the sinuses and the lungs. Your body is responding to some sort of irritant and is creating the phlegm to combat the issue. It can be related to a bacterial infection, such as bronchitis, sinusitis or pneumonia. It could be a viral infection like your regular, run-of-the-mill upper respiratory infection. It can be produced by people who have chronic lung disease, such as COPD, cystic fibrosis or bronchiectasis. It’s a part of environmental allergies and asthma as well.

Just having a productive phlegmy cough or a runny nose doesn’t really give you a specific diagnosis. But phlegm’s texture and color are clues to identifying the health issue that ails you.

The Phlegm Color Spectrum

Yellow/green phlegm

Yellowish, green phlegm is likely related to an infection. The type of infection isn’t really able to be discerned by the color itself.

The first step would be to talk to your primary care provider. They’ll ask questions such as how long have you been sick, is there someone sick in your home or at work, have you had a fever, chills, muscle aches or pain. These questions will help your doctor determine if you need antibiotics or if it’s something they can watch for a little longer and see if you can make it through without antibiotics.

Pink, red or bloody phlegm

If you’re coughing up red, pink or bloody phlegm, you should be seen by your provider. It could be related to an infection or to cancer in some cases. If you’re a smoker and you’re coughing up blood, it is worrisome. Your doctor may take a more in-depth health history and order a chest X-ray before making a diagnosis.

White phlegm

Allergies, asthma and often viral infections cause white phlegm or phlegm without a lot of color to it. It really depends. If it’s associated with underlying inflammatory conditions like asthma or COPD, it might indicate that your underlying issue isn’t as controlled as it needs to be, and your chronic disease management may need to be updated.

If it’s related to a viral upper respiratory tract infection, you can probably wait it out. If it is allergies, you may need to have a more aggressive allergy regimen, take an antihistamine, a nasal steroid or see an allergy specialist.

Charcoal or gray phlegm

We tend to see charcoal or sooty-looking phlegm in people who work in coal mines and factories or are really heavy smokers.

If you work in a factory where there’s a ton of smoke and you don’t wear a mask, you’re inhaling all that in and it’s causing an inflammatory reaction in your airways that produces phlegm. The irritants are mixed in with the phlegm and when you cough, it comes out.

Same thing with cigarette smoking — sometimes we see patients who are smoking two to three packs a day who have a productive cough. A lot of times, they’ll have a little bit of gray or smoky tinge to their phlegm because of the smoking.

If you have symptoms of an infection, we’ll give you both antibiotics and some steroids in certain cases to get the inflammation down. If it’s simply related to occupational exposure (you work in a smoky environment or construction and aren’t being diligent about wearing masks), we’ll tell you to be more careful with practicing occupational safety by wearing the appropriate personal protective equipment.

Brown phlegm

Sometimes, people who have significant chronic lung disease can cough up a brownish or sticky-looking phlegm that’s a little rarer than the traditional colors. Really dark brown, sticky phlegm is seen in patients who have cystic fibrosis or bronchiectasis, which is a chronic lung disease. The phlegm is brown because of blood and the intense chronic inflammation that comes with the chronic disease state. The bacteria camp out inside the lungs and cause very gradual changes in the consistency and appearance of phlegm.

If you have chronic lung disease, you may be used to seeing brown phlegm. In those situations that we call an acute exacerbation of your underlying cystic fibrosis or bronchiectasis, you may require antibiotics. If you have resistant bacteria growing in your lungs, you may need to have IV antibiotics or an aggressive regimen to keep things under control.

How long will the phlegm last?

The duration of the phlegm in your system depends on the cause.

- For bacterial infections, even without antibiotics, it can be self-limiting and will go away in 10 to 14 days.

- Viral infections can last a little longer, so sometimes up to three weeks, depending on the season.

- Inflammatory conditions like asthma and COPD typically don’t necessarily get better unless the disease is treated more aggressively.

Remember, your body is doing its job when phlegm is being produced. It shows that it’s addressing some sort of assault, be it an infection or an allergy or an irritant that’s in your lungs or your sinuses — that’s how your body fights those assaults.