He put off the COVID-19 vaccine. It cost him his lungs.

Kodie Edler, 28, is a symbol of survival now, but he’s also a cautionary tale. He wants to tell the world: Don’t be like me.

As Kodie Edler walks the fourth floor of the Ohio State Richard M. Ross Heart Hospital on October 21,2021, he picks up a following. A cluster of health care workers stare at him in wonder.

All around him, strangers light up. Eyebrows raise and eyes crinkle, smiles hidden behind surgical masks.

“You look so good,” says staff nurse Chelsey Corroto, her eyes welling with tears. “You’re not gonna remember me.”

This is true. Edler has no memory of the 2½ months of his life when Corroto and countless others worked frantically to keep him alive. The 28-year-old awoke sore and uncomfortable, unable to talk. Beneath his gown he’d discover a mustache-shaped incision, stretching armpit to armpit, where surgeons had opened him to remove a pair of lungs ravaged by COVID-19.

“Almost none of them remember their time on the fourth floor because they’re so sick,” says Veena Satyapriya, MD, a critical care physician in the cardiovascular intensive care unit who met Edler the night he arrived at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. “And maybe that’s a good thing.”

Edler completes his victory lap, but the short walk around the ICU is exhausting. He pauses at one doorway. Inside is a man who’s a lot like him — young, stricken by COVID-19, emerging from a deep, fitful sleep after a transplant. Edler sees the patient and his concerned father and the whiteboard they use to communicate, and the heartbreaking familiarity of it all floods over him.

“You’ve got this,” Edler says to the patient. “It’s gonna be some long days, but I know you can make it.” He wishes he could give him more, but that’s all he has. Words of encouragement. Living, breathing proof that you can pull through the worst of it.

Edler is a symbol of survival now, but he’s also a cautionary tale.

Edler wants to tell the world: Don’t be like me.

JUNE 2021 — He intends to get the COVID-19 vaccine, but he’s busy. Kodie Edler is a son following in the footsteps of a father so devoted to pizza that he holds a world record for tossing and baking pies. At 5 he was folding boxes for the elder Edler, and now he’s a director of operations at a popular pizza chain, on track to becoming a franchisee overseeing 25 stores in northwest and central Ohio. He’s in his car a lot, driving from store to store, stressing about staffing levels.

His COVID-19 worries revolve around business, not his personal health. Besides, his brother caught the virus in November, and apart from some lingering issues with taste and smell, he seems OK. His octogenarian grandparents recovered from their bout with COVID-19 in January without a problem.He’ll get around to getting the vaccine. Eventually. Maybe after this trip.

He and his wife are about to celebrate their two-year anniversary, so they plan a vacation to link up with family in Las Vegas. It’s an 18½ hour drive to Denver from their home in Findlay, Ohio, and they stop over to tour the Mile High City before white-knuckling the rest of the way through the mountains. In Vegas, they do it up properly, hitting the tourist attractions and casinos and feasting on lavish meals.

The drive home is where things start to turn. Edler is somewhere in the middle of Iowa when his hands begin to shake. He’s a sizeable guy — 6-foot-3, 280 pounds, known to wear shorts in the winter — so he’s not used to feeling so cold. Especially in the heat of summer.

It's 3 a.m. when he wakes his wife. Should we find an emergency room? she asks. No, he says. We need to be in Findlay if we’re going to go to the hospital. His wife drives the rest of the way. Edler curls up on a blow-up mattress in the back of the van and shivers beneath a blanket. When they get home at 9 a.m., they head to different rooms and collapse.

JULY 10 — Edler’s mom drives him to a local emergency room, where he tests positive for COVID-19. He’s given ibuprofen and discharged with a pulse oximeter to measure his oxygen levels, and told to return if he dips below 90.

July 13 — With his oxygen levels consistently in the 80s, Edler heads back to the hospital, where he’s admitted and put on oxygen and pain medication. His wife also gets sick with COVID-19 but stays at home and recovers.

Edler will remember the next five days, including the moment an anesthesiologist shakes his hand and says: “We’re probably going to have to put you under.”

And that’s it. He doesn’t wake up for 2½ months. But his family lives through what comes next.

Aug. 3 — Edler’s father, Brian Edler, chronicles his son’s progress on Facebook.

Today’s update sounds both grim and promising. Edler is critically ill. He’s been transported to the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center for lifesaving care, where, because he hasn’t responded to any of the usual treatments, he’s been placed on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or ECMO.

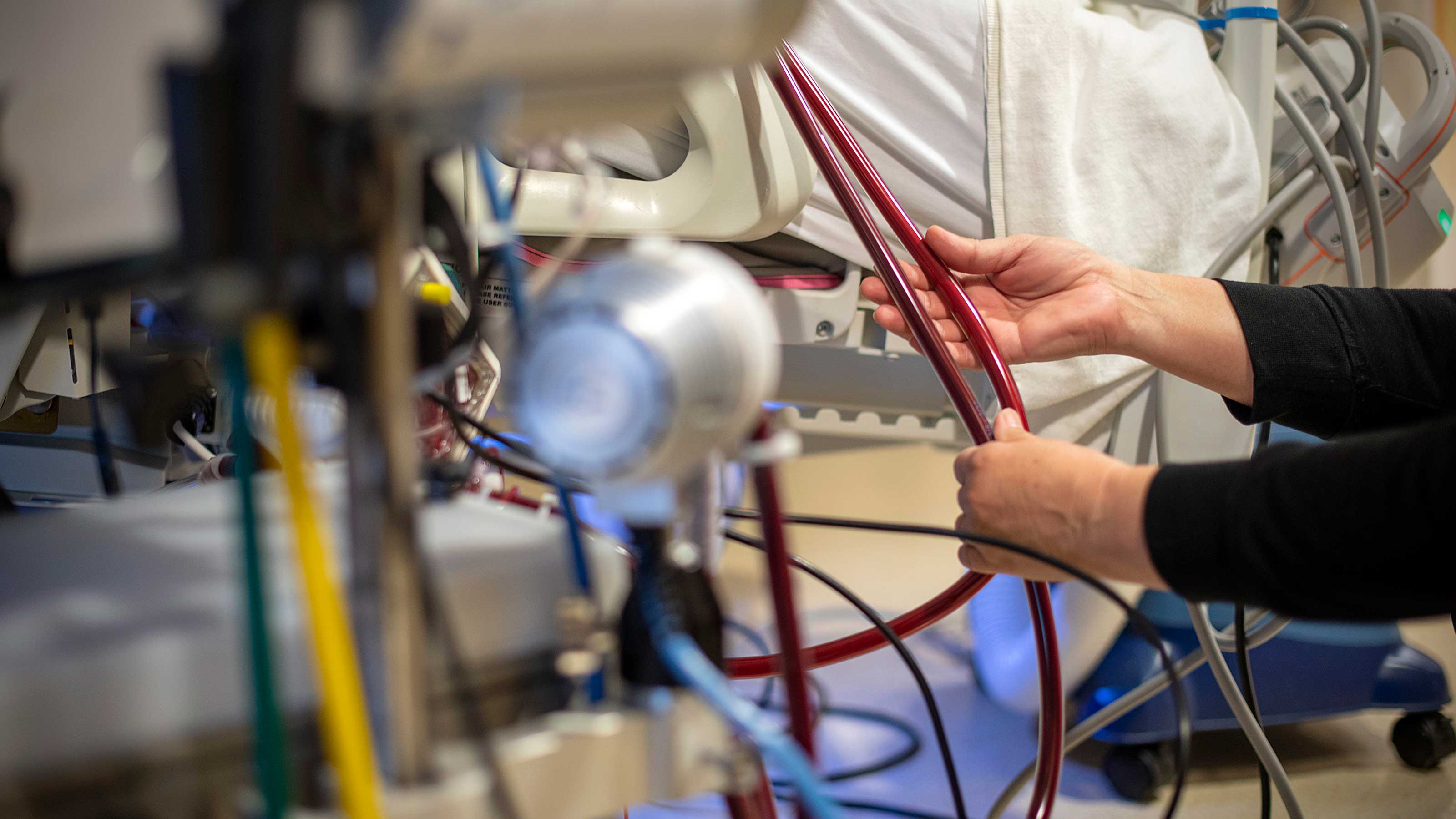

ECMO is extreme life support. It’s a way for his heart and lungs to rest while a machine circulates his blood to keep his body alive. For COVID-19 patients on the brink of death, it’s often a last resort, and it’s anything but delicate.

“There are basically tubes the size of garden hoses that draw blood out of your body, using a pump that runs it through an oxygenator and returns it back to you,” says Satyapriya.

Satyapriya is the critical care specialist who cared for Edler at Ohio State and is the medical director of the ECMO program. “It requires a surgical procedure to put them in, and there can be lots of complications.”

ECMO buys time, but as Brian Edler meets other families grieving losses of loved ones on ECMO, he learns there might not be much of that left. He sees his boy surrounded by tubes, and the worry churns in his gut. But Edler, a member of his county’s health board, also sees an opportunity: A chance to show, in real time, just how awful all of this really is — and how it might have been prevented.

“They are moving his ECMO cannulas from his legs to his neck,” the father writes on Facebook. “They are also putting his intubation tube in through a tracheostomy as he has been fighting the intubation tube more and more. … Yesterday he tried to levitate off the bed again fighting the vent tubes … His 100 lb nurses needed some help holding him down while they waited for the meds to knock [him] out again.”

The post continues. “If you have not been vaccinated yet and are on the fence,” Brian Edler writes, “think of what Kodie has gone through and the family …

“To be clear, Kodie was not vaccinated. The last words to his mother at the hospital were, ‘Sorry Mom, I wish I would [have] had the shot.’”

Aug. 5 — At a press conference of public health and hospital leaders, Dr. Satyapriya shares Edler’s story.

He’s stable, she says, but fighting for his life. “His wife and his parents are really beside themselves right now.”

Satyapriya reads a message from Edler’s wife and family during the press conference.

“Getting vaccinated is a serious decision, but there are consequences for both choices,” it says. “Not getting vaccinated could mean you and your family have to deal with the brutal side of COVID.

“Your family may have to experience the helpless feeling of waiting outside for news every few hours because they can't go in to see you. That sinking feeling when the phone rings because it could be a nurse or a doctor telling them that your lungs aren't responding enough to the oxygen machine. Or the fear of being one hour away from the hospital because they might not get there in time to see you through the window. These are all very real situations that have made the last three weeks feel like a terrible dream.”

Aug. 10 — “He had a bad day,” Brian Edler writes on Facebook. “Speaking with transplant team in the morning…”

Aug. 24 — Doctors review the extensive damage to Edler’s lungs and decide his only option for survival is a lung transplant. An algorithm generates a lung allocation score based on how sick a patient is and how likely they are to survive a transplant, and on a scale from 0 to 100 — 100 being the most dire — Edler scores a 77.5.

In less than two months, COVID-19 has almost completely destroyed his lungs.

“I've been in transplant now almost 30 years, and when this whole thing started with COVID back in the spring of 2020, I was anticipating that we were going to see some fallout,” says David Nunley, MD, medical director of the Lung Transplant Program at the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center. “But I was anticipating that it would be people coming to us later, months or years later, after they had the infection and were left with lung injury.

“Honestly, I did not foresee these — what I'm calling emergency transplants or rescue transplants — for these people who get so deathly ill that they can't get off a ventilator or an ECMO machine.” But it’s happening, over and over.

By the end of the year, Ohio State alone will have performed over a dozen COVID-related lung transplants. Edler will be one of them.

Sept. 2 — “Doctor called at 9:53 p.m.,” Brian Edler writes. “Lungs are in and they are great lungs.”

A healthy 28-year-old’s lungs should be light pink and spongy, like an angel food cake, says Bryan Whitson, MD, PhD, Ohio State’s lead lung transplant surgeon and director of Thoracic Transplantation and Mechanical Circulatory Support. What he removes from Edler’s chest are dense and dark, more akin to a piece of liver.

“We don’t know why this happens to some people and not others, but what we know is that for the people who get really bad COVID, it’s very quick,” Whitson says. “The way these patients present with their lung failure is very similar to someone with advance pulmonary fibrosis. The lungs are just … shot.”

Edler’s old lungs are so bad that it’s clear ECMO was the only thing keeping him alive. But his body takes to these new lungs. The transplant is a success. It’s his first and best hope that he’ll soon be able to breathe on his own again.

The days that follow are filled with new and old firsts: first breaths, first words, first steps. Edler sits up. He speaks. He goes outside. He loses the massive water weight that ballooned his hands and feet. His father’s Facebook posts — which have captured local media attention and spurred, by his count, more than 1,000 people to get vaccinated — grow increasingly optimistic.

“WOOOOHOOOOO,” Brian Edler writes.

After 86 days in one hospital or another, Edler is finally discharged to outpatient rehabilitation in Columbus.

Pictures show him beaming in the back of a car, wearing a shirt that says, in big letters, LIVING PROOF. “Prayers answered,” his father writes, “and then some.”

Oct. 25 — He’s watching The Price Is Right as he pedals on a recumbent bike, drumming up a sweat in one of his last pulmonary rehab sessions at Ohio State before he returns to Findlay. Soon he’ll be able to drive again. He’ll be able to pick up where he left off. But so much has changed in four months.

A few days earlier, Edler returned to the hospital in respiratory distress. He felt like something was choking him. Doctors couldn’t find anything wrong. It might have been fatigue, or maybe anxiety. For Edler, it was a reminder of where he’s been, and the long road ahead. Lung transplant is not a cure. Half of all recipients die within seven years, Nunley says, and only about one-third live past a decade. “This is not like you can just put in a set of organs and they go about their merry way,” he says.

There are strict rules to follow: diet and exercise, medical appointments, regular lab work. For the rest of his life, Edler will have to take medications to keep his body from rejecting the organs he wasn’t born with. He’ll continue to travel to Columbus every week to check in with his transplant team. “They’re with me for life, they say — in a joking manner, but they really mean it,” he says.

Edler has tried to read his dad’s Facebook posts, but he didn’t get far. He’s not ready. His tender conversations with his wife remind him that the people he loves remember every agonizing day he doesn’t. He’s started a letter to the family of his organ donor, but it’s hard to know what to write. There’s so much to say. He’s alive. He survived. This is to be celebrated, but it comes with new responsibility. Now that he’s awake, now that he has a voice, he’s continuing what his father started.

“A smart man learns from his mistakes, but a wise man learns from others,” Edler says. “I have no problem as a leader to say, ‘Hey guys, I’ve messed up.’ I wasn’t careful. I didn’t take all of the precautions I could have.

“Now, I can live and learn from my own mistake and hopefully be smarter man for it — and hopefully breed a whole bunch of wise people for it.”

Editor’s note: As what we know about COVID-19 evolves, so could the information in this story. Find our most recent COVID-19 articles here and learn the latest in COVID-19 prevention at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Some photos and videos on this site were filmed prior to the COVID-19 outbreak or may not reflect current physical distancing and/or masking guidelines.

Ready to get vaccinated?

We have appointments available as early as today.

Schedule now