Overcoming the racial divide in rural veterinary medicine

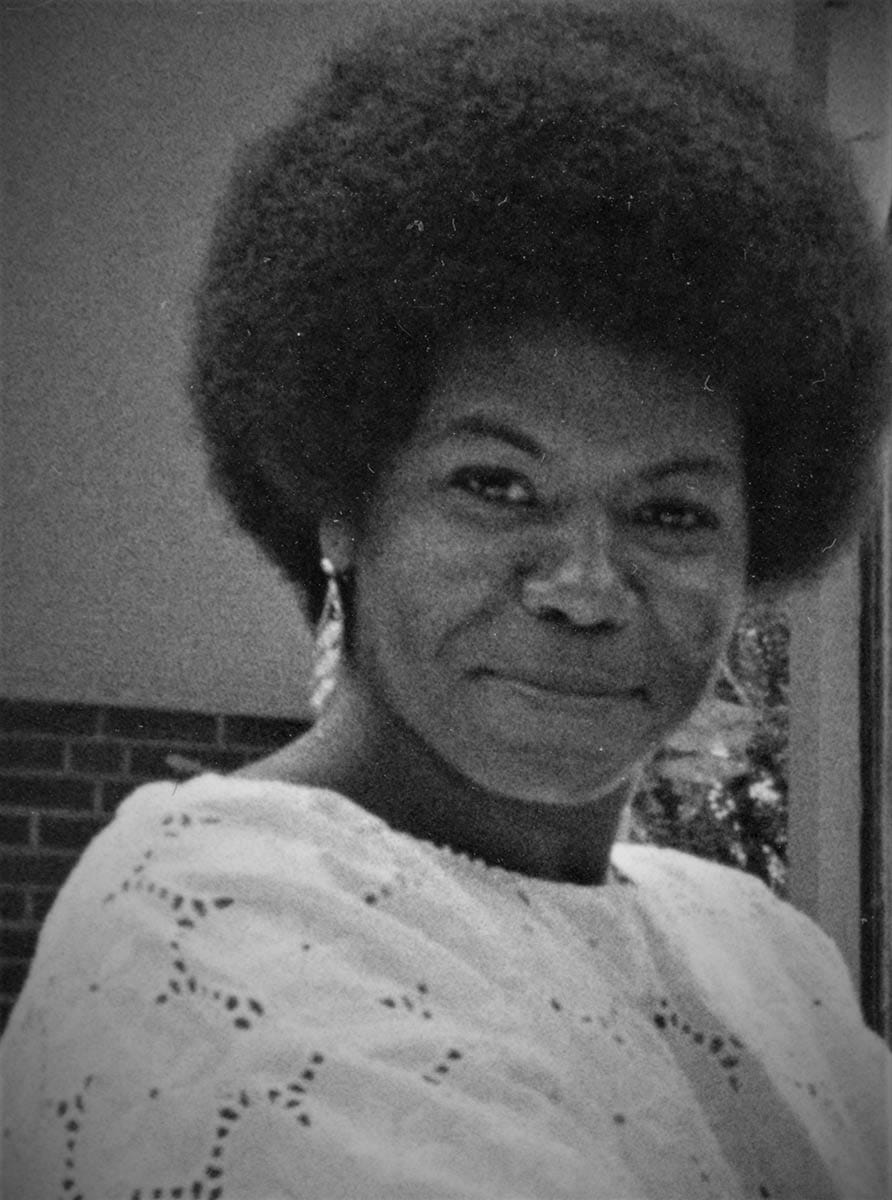

Linda Randall, DVM, was the first Black female veterinarian to own a practice in her rural county. She wants to ensure others can bridge the same gap.

Nadji’s barks echo through the hallway. She wants in where the other dogs are.

When her owner guides the German shepherd onto the course, she’s still barking while her classmates rest in their crates. Eventually quieting down, she too does what’s expected: She jumps the low hurdle before returning to her owner for the first handful of treats.

“That was good,” says Linda Randall, DVM, a dog trainer and alumna of The Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine. “Praise her the whole time. Then spend some time with her in the hallway so she doesn’t think: ‘Good girl. Now you’re going back in your crate.’”

Though she’s not a parent herself, what Dr. Randall teaches about dog training is a lot like good parenting. Give guidelines. Offer incentives. Praise often. In her classes, no dog wears a shock collar. There’s no jerking on leashes. No one yells.

The focus is on positive reinforcement as dogs and their owners learn to master an obstacle course of tunnels and hurdles, a seesaw and an A-frame.

Dr. Randall’s path to where she is today was an obstacle course in itself. Long before opening One Smart Dog in Seville, Ohio, in 2022, she was the first Black woman to start a veterinary practice in rural and predominantly white Medina County. What she faced to become a veterinarian, then to run her business, drove her to work toward a more diverse field of veterinary medicine, serving on the admissions committee for Ohio State’s College of Veterinary Medicine.

“She’s made a place for herself in a world that wasn’t necessarily ready to accept her, especially the veterinary world,” says Pam Wagner, who has taken several dog training classes from Dr. Randall.

“Being a woman was hard. Being a Black woman was definitely harder,” Wagner says. “Yet she continued then and still continues.”

A winding path to veterinary medicine

Dr. Randall’s focus on positive reinforcement stems in part from her own life experience facing the opposite: repeatedly being told “No.”

In Southbury, Connecticut, where Dr. Randall grew up on a chicken farm, she and her brother were the only people of color at their school in the 1970s. Classmates relentlessly bullied them with threats and slurs. It made it difficult for her to speak up in classes, to even get through the hallway. Trying to rise above it all, she’d crash with bouts of depression.

When she told her high school’s academic counselor she wanted to become a veterinarian, he was flabbergasted and tried to dissuade her. He said not many women or Black people were veterinarians. He reminded her she had failed a physics course and didn’t like math. “What else do you want to do?” he asked. She said: write. That year, she wrote in the yearbook she wanted to be a journalist.

When she told her high school’s academic counselor she wanted to become a veterinarian, he was flabbergasted and tried to dissuade her. He said not many women or Black people were veterinarians. He reminded her she had failed a physics course and didn’t like math. “What else do you want to do?” he asked. She said: write. That year, she wrote in the yearbook she wanted to be a journalist.

She liked writing and had a story to tell, and she wanted to tell the stories of others, too. From rural Connecticut, she moved to Indiana to Earlham College, a small liberal arts Quaker college that offered her a scholarship. She majored in English.

After college, she became an English teacher, first in New York, then in Nigeria, responding to an ad for the position in The New York Times. Though a military coup in Nigeria shortened her time abroad, she planned to eventually go back to West Africa, to help the nomadic cattle herders have healthier herds. That ambition rekindled her interest in becoming a veterinarian. If she could live and teach in Nigeria, surely, she figured, she could take on the challenge of getting into a veterinary school.

“I listened to people who would say how hard it was going to be, and then I did it anyway,” Dr. Randall says.

It wasn’t easy, though. In a year and a half, while earning money selling Avon door to door and cleaning houses, she crammed in all the science and math courses she needed to apply and met her goal. She got into several veterinary programs and chose Ohio State’s College of Veterinary Medicine.

She would quickly discover another hurdle when she graduated from the program: finding her first job as a veterinarian. It was 1981. She was a Black woman in a profession dominated by white men. She mailed out over a hundred resumes. When she removed her picture from her resumes, she landed some interviews. The owner of a veterinary practice in Philadelphia called her after one of them. He couldn’t hire her, he said. He thought she was qualified but his mostly white customers wouldn’t accept her.

“By that time, I was just hardened to all of it,” she says. “It was a story I kept telling people. The more I told the story, the less power it had.”

Out on her own

Eventually, Dr. Randall got a job working with a veterinarian in Medina County. Then, in 1991, she set off on her own. She started Cloverleaf Animal Hospital in Westfield Center, Ohio.

Eventually, Dr. Randall got a job working with a veterinarian in Medina County. Then, in 1991, she set off on her own. She started Cloverleaf Animal Hospital in Westfield Center, Ohio.

Just a couple of miles away, in downtown Lodi, a small group of protesters held up placards, attempting to stop her, the first of several tactics that played out for years. People threatened her. They spraypainted racial slurs on her building, where she also lived. One night, police shined bright flashlights into the windows and then made their way inside. Someone had called them. They said she had been murdered.

Some of the resistance Dr. Randall had expected, but she wasn’t quite prepared for the emotional toll of it all. She sought support from calls to her mom in New York, from friends and her former professors at Ohio State, who reminded her how competent she was.

At times, she considered leaving her business, leaving Medina County, leaving Ohio. She even interviewed for jobs in Connecticut but decided against going. That would have meant giving up and giving in.

“Instead of letting the threats and discrimination drive me away, I dug in and said: ‘What do I enjoy doing most?’ And then I did it.”

She liked meeting new people, making friends with veterinarians and others in the community. She began volunteering for the local domestic violence and rape crisis organizations and joining veterinary organizations.

While running the veterinary hospital, she started a dog training business, The Agility Underground, and ran it behind her veterinary hospital.

It was a natural step for a woman who had trained several dogs of her own. She has long appreciated how dogs can be so sensitive to the feelings of people around them, and how they’re always up for adventure, ready to try something new, as she is.

Inspiring inclusivity at home and for future veterinarians

Dr. Randall is not the typical face of veterinary medicine, of dog training nor of the population of her rural county. Yet for over 16 years, she served as the chair and face of Agriculture Day for Leadership Medina County, a nonprofit organization that trains local leaders. She’s led tours of farms giving talks about the present and future of agriculture in the county.

Colleen Rice, a former director of Leadership Medina County, describes Dr. Randall as part veterinarian and part social worker. She asks a lot of questions. She listens and has always worked to make sure the programs the organization put on were geared toward a wide audience, that no one was left out.

“She would let me know if there’s something we could do to be more inclusive,” Rice says. “That’s just who she is.”

She brought the same perspective to her role as a member and then president of the Ohio Veterinary Licensing Board in the late 1990s, and to her current position on the admissions committee at the Ohio State College of Veterinary Medicine.

She brought the same perspective to her role as a member and then president of the Ohio Veterinary Licensing Board in the late 1990s, and to her current position on the admissions committee at the Ohio State College of Veterinary Medicine.

“Her thought process, her ability to dig deeper into our process is unmatched,” says Sandra Dawkins, MPA, director of admissions and recruitment for the Ohio State College of Veterinary Medicine.

“We depend on her perspective as we continue to refine what we do, so that we have the most fair and equitable admissions process in the country."

Dr. Randall wants to know that people who go into veterinary medicine after her are more likely to feel comfortable in their own skin and to thrive in the profession.

“It’s important they don’t feel that everywhere they go they’re ‘the only,’” Dr. Randall says, “and that they don’t have to make their way through, as many of us had to.”

But it was that obstacle course, that sometimes painful and frustrating obstacle course Dr. Randall negotiated that motivates her to do more than cure ailing pets and help dogs cross the finish line first.

Her students, she hopes, see her race as a plus, possibly even an opening. Having her as an instructor just might lead them to get to know or befriend the handful of people of color in their classes or on their sports teams, the people who might, at times, feel left out.

“I try very hard,” she says, “to show them how the world can be.”

Compassionate, cutting-edge care for pets and animals

At The Ohio State University Veterinary Medical Center, our top priority is making the world healthier for animals and the families who love and care for them.

Learn more about our services