Family ties: Considering genetic testing when Parkinson’s disease runs in the family

Genetic testing is helping patients and researchers discover more about Parkinson’s disease.

He’s not the nervous type, but I remember my father, Rick Myser, seemed anxious. It was the summer of 2013, and then 64, my dad was about to tell us he’d been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease (PD).

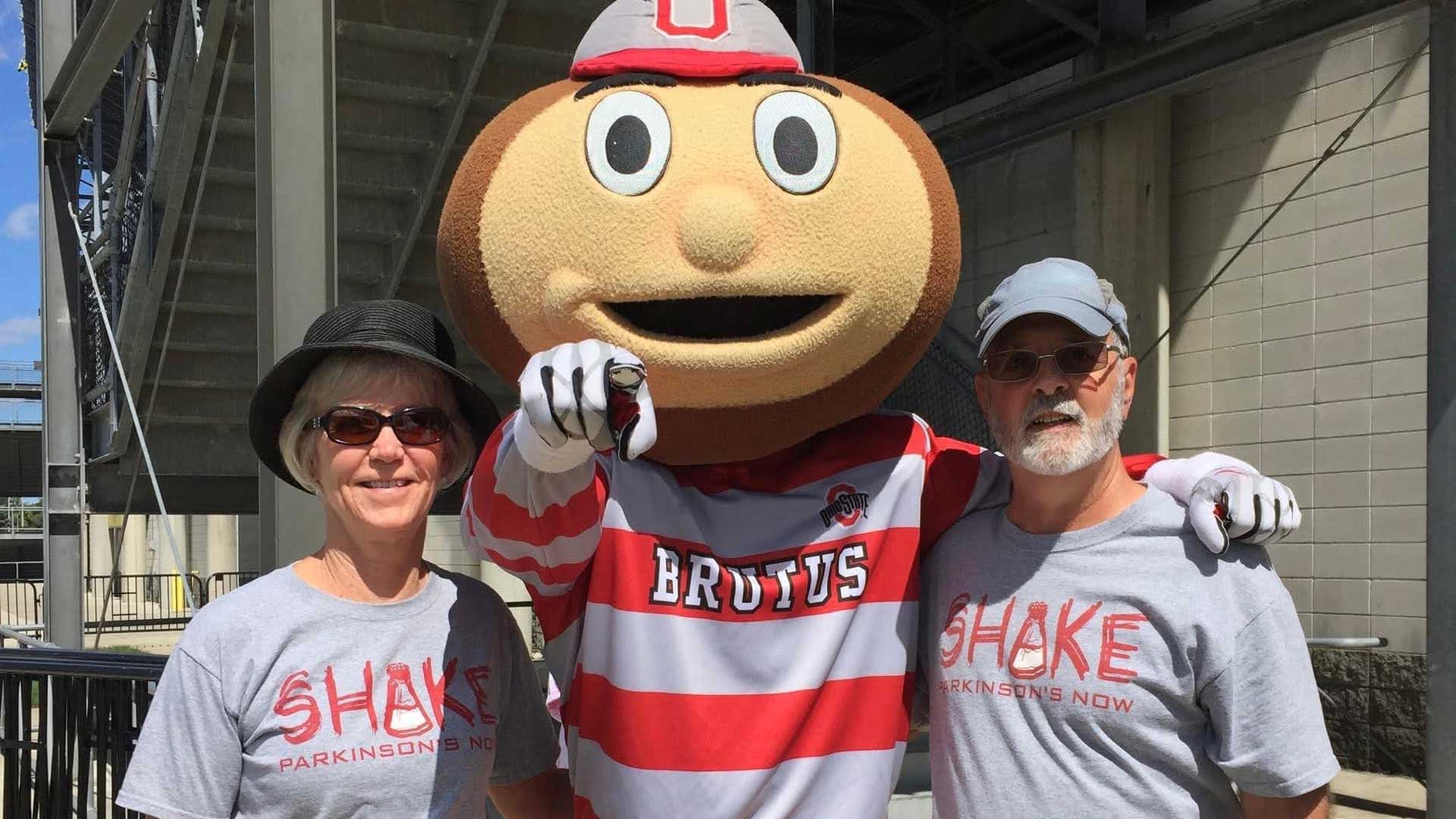

I also remember there were tears, but not much shock. Those closest to Dad had witnessed his motor patterns change: His left foot dragged, his left arm often “stuck” tightly at his side as he walked. And the Myser family was already quite familiar with PD, as we’d watched my grandfather battle the disease in the 1980s and ’90s. We also knew that my dad’s grandmother and a cousin had the disease.

Ten years later, we know even more about the disease, thanks in large part to researchers across the globe, the Parkinson’s Foundation and, of course, Michael J. Fox. We also know a lot more because of the Center for Parkinson’s Disease and Other Movement Disorders at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, an ambitious and growing research center that currently sees about 1,200 patients a year. Dad has been a patient since his diagnosis.

Now, as part of a massive national initiative to test and map the genes most relevant to the disease and provide free genetic testing and genetic counseling to Parkinson’s patients and their families, the center is poised for even more breakthrough PD discoveries.

Parkinson’s disease continues to expand across the population

Parkinson’s disease is the second most common neurological condition in the world behind Alzheimer’s disease, with at least 10 million people worldwide currently living with the disease. Approximately 90,000 Americans are diagnosed each year, and the general population has a 3-6% risk of developing it.

PD occurs when the brain cells that produce dopamine are damaged or die off. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that some of us may know as the “feel-good” chemical, as it is released and allows us to feel pleasure and satisfaction. If we don’t have or produce enough dopamine, the brain has trouble communicating with other parts of the nervous system.

In the case of Parkinson’s, that dopamine deficit results in symptoms most often witnessed first through common movement deficits, including tremors, facial masking, slowed movements, limb or neck rigidity and poor balance or coordination. As symptoms worsen, patients can have difficulty chewing and swallowing or trouble raising their voices.

And while it’s less obvious to the outside observer, Ariane Park, MD, MPH, associate professor of Neurology at The Ohio State University College of Medicine, says PD patients are often impacted by nonmotor symptoms, which can include depression, anxiety, apathy, hallucinations, constipation, sleep disorders and cognitive issues.

Ten years on, my dad’s symptoms have been relatively slow to progress. The medications he takes can either replicate or increase the production of dopamine. Research shows that physical activities can moderate symptoms, and anecdotally, when Dad is working out regularly, he seems to move better. He says when he feels “off,” it’s usually because he missed his medication dose. That doesn’t necessarily mean he feels great, though, as he’s also dealing with vision issues, restless leg syndrome and other symptoms and drug side effects.

Thus far, researchers haven’t pinpointed the exact cause of the nerve-cell damage that results in Parkinson’s disease. There is some understanding that pesticide exposure and other industrial pollution can cause it, and it’s quite possible genes play a role, as historically about 10% of those with PD have some genetic change related to the disease.

Mapping genes to aid our understanding of Parkinson’s disease

That’s where the Parkinson’s Foundation’s PD GENEration study, a national initiative to test and map the genes most relevant to PD, steps in. In late 2022, Ohio State was named the 10th PD GENEration study site. Ohio State has also recently been designated a Comprehensive Care Center for Parkinson’s disease by the Parkinson’s Foundation to recognize health care facilities that provide exceptional care to those with Parkinson’s disease.

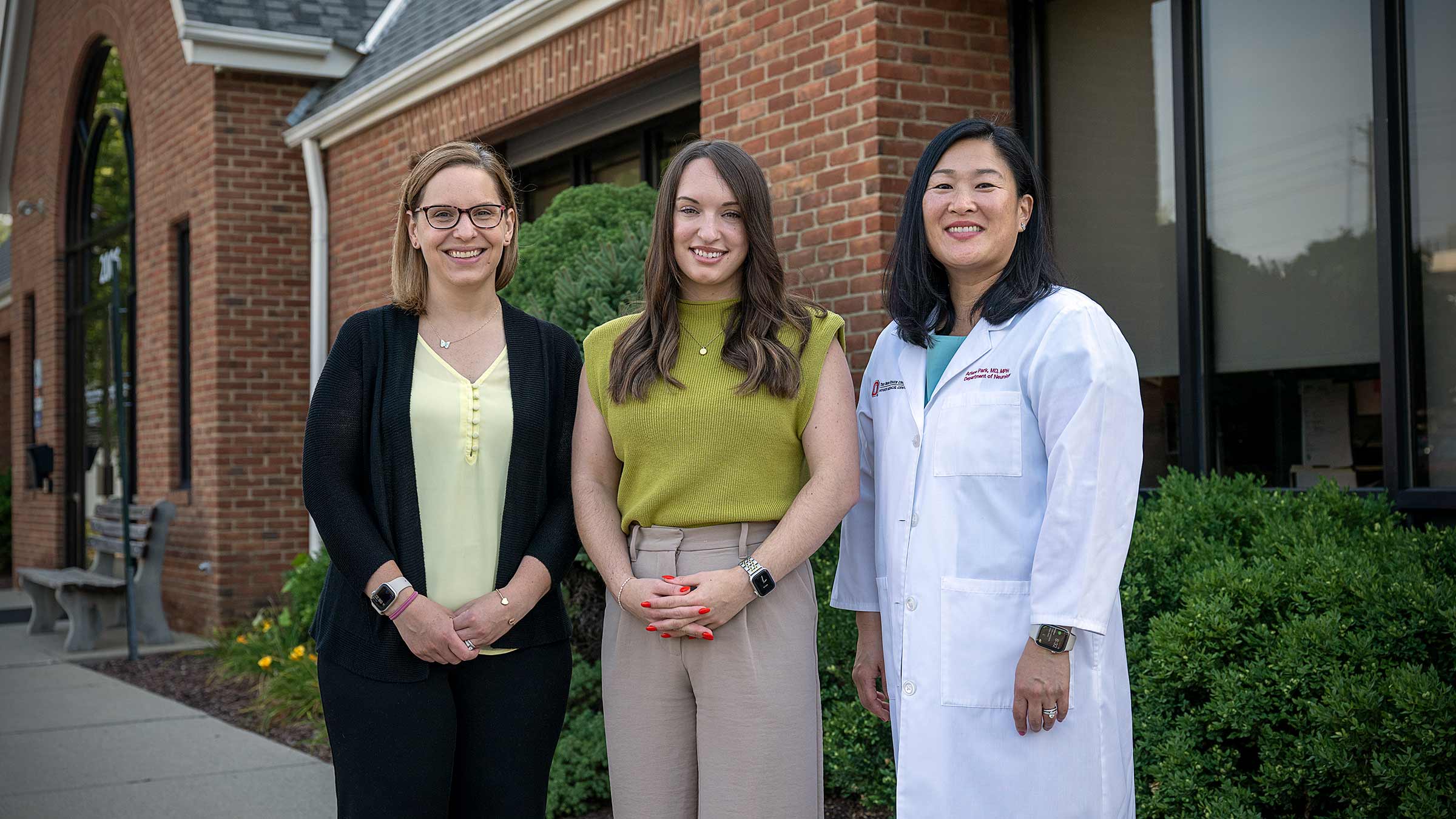

“We’re extremely excited and proud to be a part of this national effort to improve our understanding and advancement of scientific research by providing free genetic testing and counseling to Parkinson’s patients and their families,” says Katherine Ambrogi, BSN, RN, CCRP, clinical research manager for Parkinson’s research at Ohio State.

“As an academic medical center, we allow our patients to take advantage of the most cutting-edge research opportunities, and PD GENEration is just one of the many opportunities offered to our patients,” Ambrogi says.

It is one of three PD GENEration centers in Ohio; however, Ohio State is the only center in Ohio offering in-person genetic counseling.

How genetic makeup shapes a potential risk for Parkinson’s disease

Victoria Klee, MS, LGC, a genetic counselor and assistant professor of Neurogenetics in the Department of Neurology, typically gives study participants a quick genetics primer, as she does for me and my dad when we meet on Ohio State’s campus. Klee explains that there are some 50 genes with a connection to PD, and the PD GENEration study targets the seven most common genes associated with Parkinson’s risk and development.

We have two copies of each gene, one from our mother and one from our father. Our DNA code can give us our brown hair and blue eyes or determine our height and shoe size. Sometimes, those genes make us more susceptible to disease, especially when there is a variation or mutation in which the DNA code is out of order, a part of the gene is missing (called a deletion) or there is an extra part of a gene (a duplication).

Those variations are what PD GENEration is looking for. In addition, the study creates a biobank of thousands of Parkinson’s patients whom researchers can continue to study in search of different links between genetic changes and the disease. More than halfway toward the goal of testing 15,000 patients, researchers have identified that 14% of participants have a genetic form of PD.

“By creating a large genetic data and sample repository, we’re able to accelerate research and our understanding of PD,” Dr. Park says. She’s my father’s lead PD physician and principal investigator on the PD GENEration study at Ohio State.

“The more we understand, particularly in patients with specific PD-related genetic mutations, the closer we are to developing better treatments and, potentially, cures,” Dr. Park says.

That’s also a big reason my dad wanted to participate. As a scientist himself, he realizes we’re still a long way from gene-based cures for Parkinson’s, but he views these and other studies — so far he’s been involved in about six at Ohio State — as a very easy way to contribute to the bank of research.

“The doctors know they can call me,” he says, laughing.

Dr. Park says the study is already giving meaningful clinical results to providers and patients like my dad.

At Ohio State, the positive hit rate for a genetic variation is a bit higher than the overall study at nearly 16% of the 140 patients tested so far, including my father, Klee says.

The Myser genetics

Klee explains that my father has one deletion on what’s called the PRKN gene — but only on one copy. While PRKN is associated with early-onset Parkinson’s disease (EOPD), a diagnosis given before the age of 50 but as early as the 30s to 40s, research so far has determined that the risk for EOPD typically occurs only when both gene copies have a genetic change.

So where does that leave me and my younger brother? Our risk for developing Parkinson’s doubles to as high as 12% simply due to close family diagnosis. And recall, we get one PRKN gene copy from Mom and one copy from Dad. That means a 50% likelihood that Dad passed on the PRKN gene with the variant. Maybe we got Dad’s “good” gene and are completely in the clear for this genetic risk.

It also seems intuitive that Parkinson’s is inherited, at least on the Myser side of the family, as we know that four relatives across three generations had the disease. However, the science isn’t so clear.

It’s because of these issues — and to provide context around results — that the PD GENEration program includes free genetic counseling, including for family members grappling with the results and considering whether to get tested themselves.

Deciding whether to pursue Parkinson’s disease genetic testing

My wife, Jennifer Webb Myser, PsyD, and I decide to meet with Klee. She first takes us through Dad’s results, then digs into the pros and cons of genetic testing for a family member like me.

On the plus side, testing can help quantify risks and my chances of progressing to Parkinson’s, potentially influencing my lifestyle choices, particularly around diet and exercise. As my wife points out in our session, it can provide our two sons with what one day might be valuable genetic info.

On the negative side, that knowledge can create a lot more anxiety for some patients and families, to the point that they’re constantly “symptom-watching” and worrying they might wake up the next day with PD. And in my case, there’s such a tenuous connection between my Dad’s gene mutation and Parkinson’s that, even if I have the variant, it might not mean all that much. Genetic testing can also uncover unrelated and sometimes unwanted information about other diseases or even family ties.

Like my father, I’m not the anxious type, preferring to worry and deal with things after they occur, or in this case, after diagnosis. However, I also like testing and playing around with data and variables in many aspects of my life, and the ability to give our kids some extra data is enticing.

So, as Sir Francis Bacon famously noted: “Scientia potentia est.” Knowledge is power.

With that in mind, I’ll follow up with Klee this week to schedule my genetic test.

Have you or someone you know been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease?

To participate in the PD GENEration study, call 614-293-4969 to schedule an appointment or click below to learn more.

Learn more