Revolutionizing memory disorder detection with a paper and pen

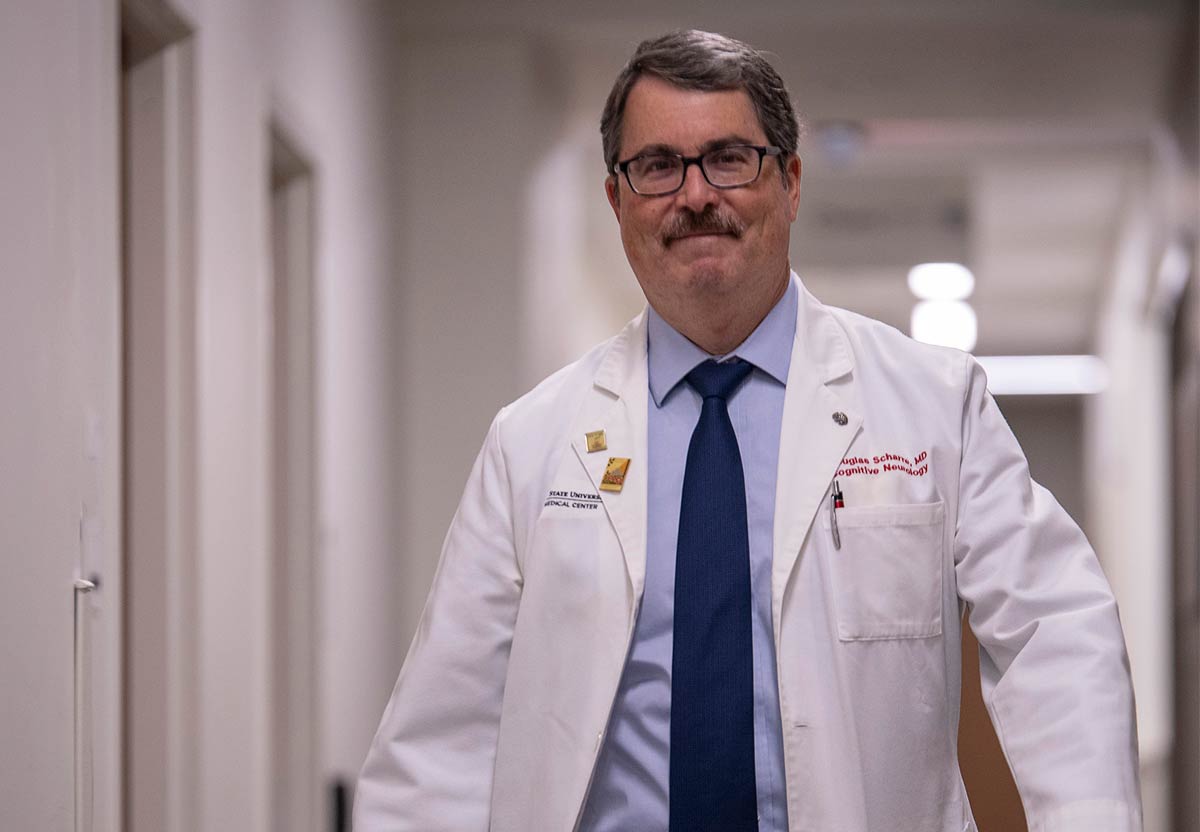

Neurologist Douglas Scharre, MD, wants the world to know that early detection is the most important tool in treating memory disorders including Alzheimer’s disease.

It would not be accurate to say that Douglas Scharre, MD, was completely on his own when he came to The Ohio State University in 1993 to study diseases affecting the brain.

“I did negotiate to have a social worker one day a week,” says Dr. Scharre, who now serves as director of the Division of Cognitive and Memory Disorders in the Department of Neurology at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center.

In the decades since, the scope of this work at Ohio State has blossomed tremendously, facilitating a multitude of new treatment options for patients and their family members grappling with devastating memory loss issues.

The Center for Cognitive and Memory Disorders is the largest clinic of its kind in Ohio, and Dr. Scharre leads a team that has pioneered a revolutionary memory test taken by millions — using the rudimentary tools of pen and paper to ensure the test’s accessibility and ease — and produced other treatments that have had an immeasurable impact on the lives of people living with Alzheimer’s disease, dementia and other cognitive afflictions.

When Dr. Scharre arrived, his closest tie to Ohio was that his mother was born in Toledo. He left Los Angeles wondering whether Columbus could possibly offer anything approaching the diversity and multitude of experiences of the city he was leaving. But the decision to move here to do this work was simple. The leaders at Ohio State believed as strongly as he did in the necessity of memory disorder research.

“They had the same vision that I did. There was a dream that we were going to build something here,” Dr. Scharre says.

“The goal was to build a program to be able to do more for individuals to help these conditions,” Dr. Scharre says.

Dr. Scharre’s colleague Arun Ramamurthy, MD, sums it up succinctly: “He basically built a machine here.”

How it all began: ‘I fell in love’

Dr. Scharre’s passion for treating cognitive conditions took root in the mid-1980s at Letterman Army Medical Center in San Francisco. During his residency there, he noticed that there was a relative lack of expertise and resources devoted to the understanding of behavioral neurology.

A presentation from D. Frank Benson, MD, a titan in the field of neurology who was teaching at the University of California, Los Angeles, at the time, set Dr. Scharre on his professional course.

“I fell in love,” Dr. Scharre says. “I wondered why I wasn’t learning about this. The different connections — one part of the brain does more of this, and it has to connect to other parts to communicate your thoughts. It results in understanding why people act the way they do. What don’t they understand?

“It’s fascinating to me — understanding the brain and how it works.”

That fascination led him to UCLA for a fellowship and then to Ohio State, where he leads a team that has developed numerous treatments to help patients with Alzheimer’s disease or other forms of dementia. A differentiator for these treatments is that they can begin helping patients much sooner than other areas of research such as drug development, which takes years to bring forth approved treatments. A recent example: Dr. Scharre’s team has studied how patients with Lewy body dementia respond while walking on a treadmill, measuring how much difficulty they have with motor skills. The results led his team to begin treating more patients with exercise on a treadmill.

The need is obvious. According to the World Health Organization, more than 55 million people are living with dementia, and another 10 million cases are diagnosed annually. It is the seventh-leading cause of death among all diseases.

The problem is only projected to intensify as people continue to lead longer lives. The United Nations reports that the worldwide population over age 60 more than doubled from 1980 to 2017, increasing to 962 million. It is expected to surpass 2 billion by 2050.

As leader of Ohio State’s Center for Cognitive and Memory Disorders, Dr. Scharre is helping bring much-needed attention to these diseases. More than 170 faculty members within the Neurological Institute contribute to the center’s work, and its Memory Disorders Clinic has more than 2,500 patient visits annually. The Memory Disorders Research Center has conducted more than 200 dementia-related clinical trials in the last 20 years.

More Alzheimer’s clinical trials happen at Ohio State than at any other Ohio medical center, giving these patients access to treatments and diagnostics not available elsewhere.

The SAGE test

The breakthrough Dr. Scharre is best known for is a treatment that is administered with a humble paper and pen.

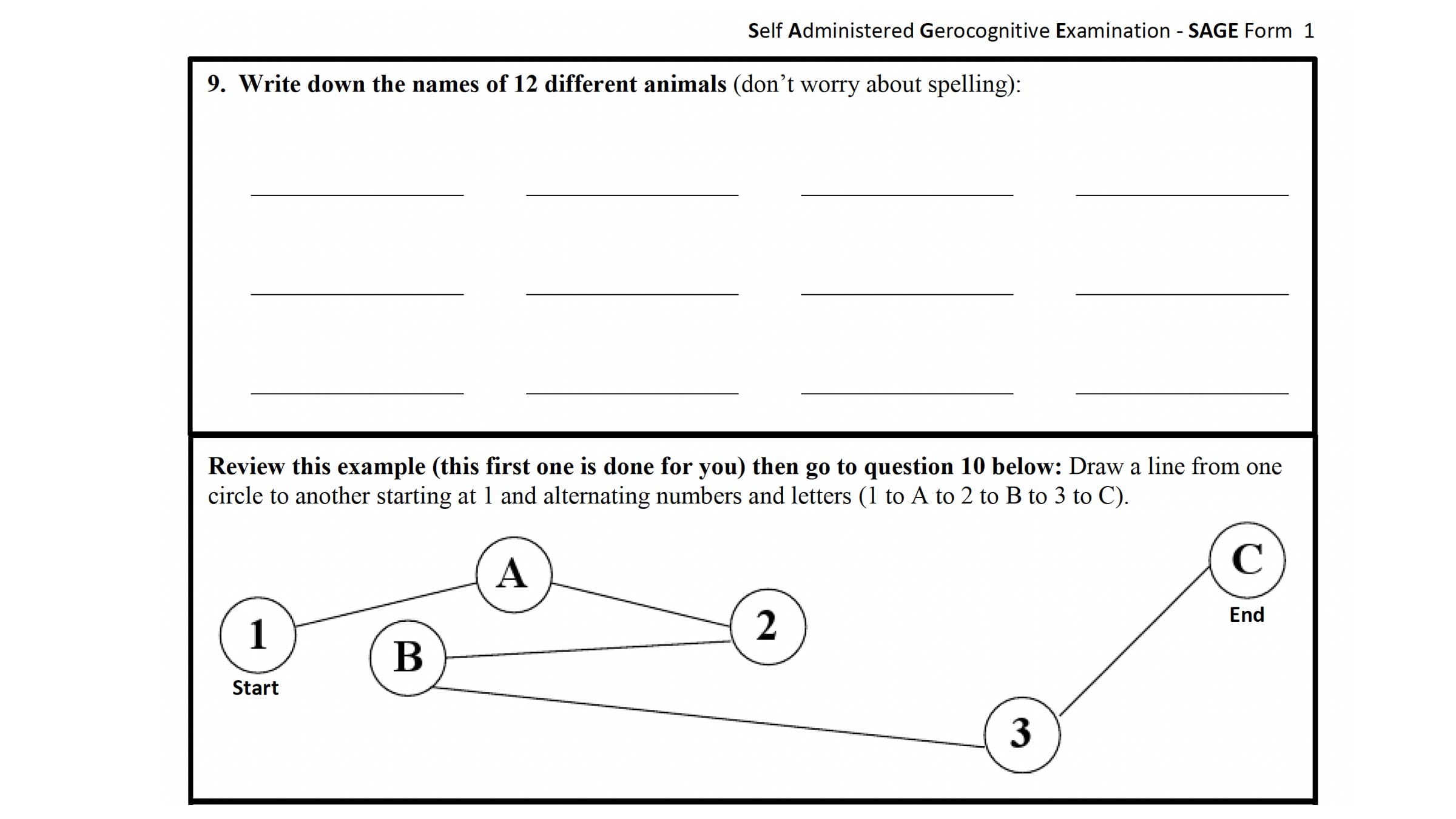

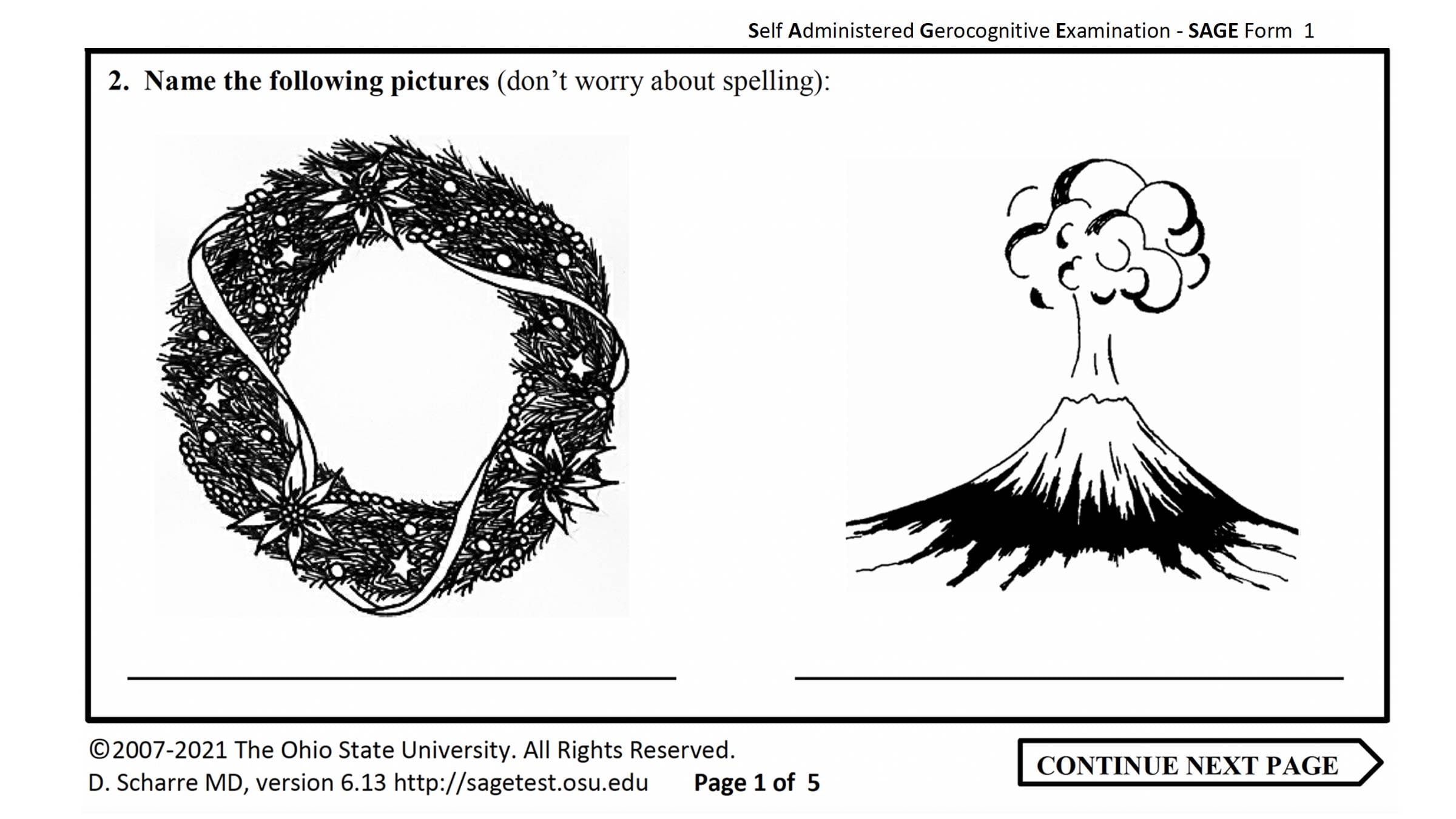

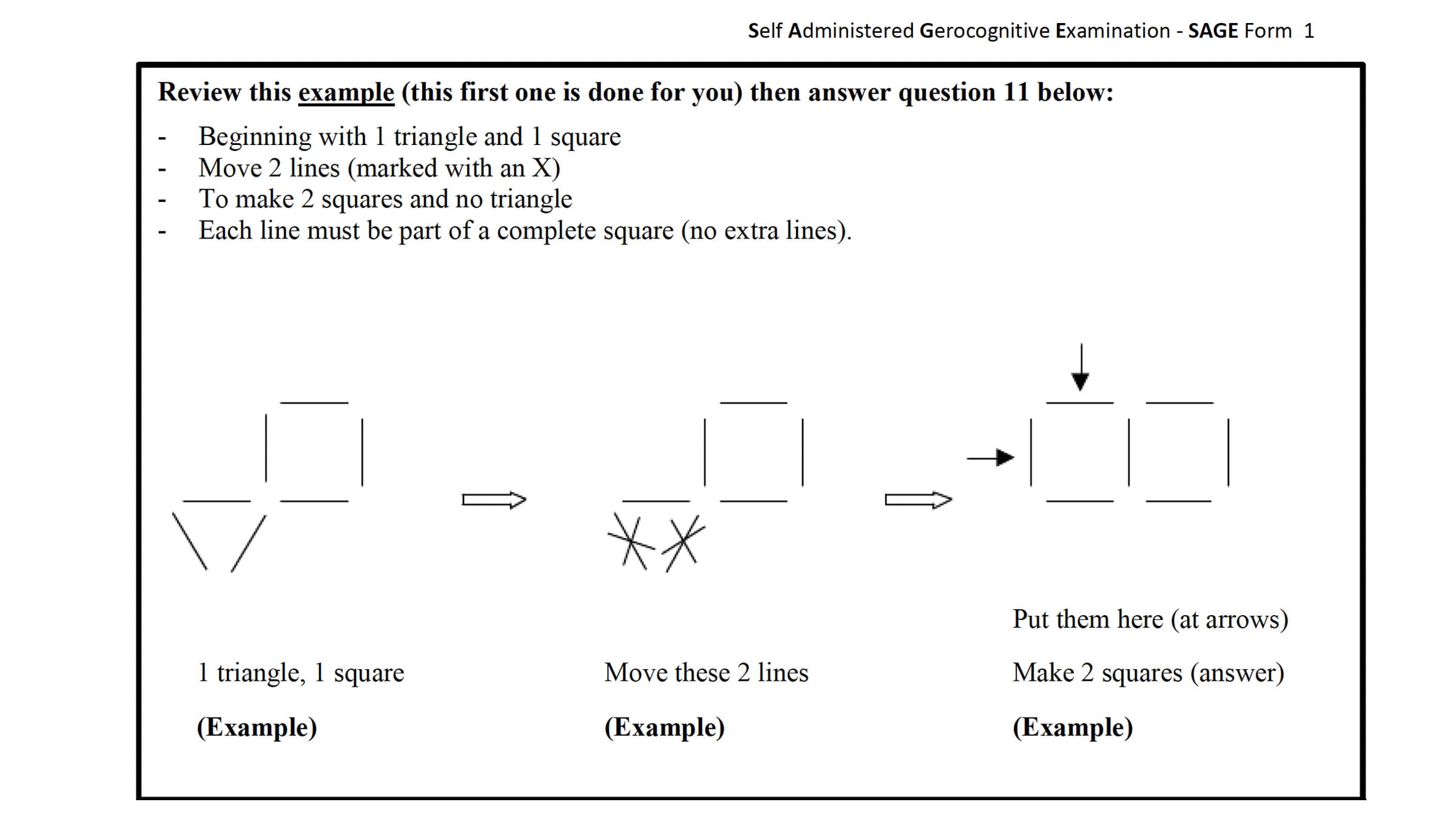

The Self-Administered Gerocognitive Exam (SAGE) is a 12-question test that assesses a person’s cognitive abilities. It’s available free online and takes most people 15 minutes or less to complete.

But behind its apparent simplicity, the SAGE test helped address a major hurdle in the treatment of dementia patients. Too often, their dementia symptoms would not be recognized early enough to connect them with effective therapies.

“When I was seeing patients with cognitive disorders, they would come in that first visit and explain situations that happened three or four years ago. How does it take you three or four years to get to a physician?” Dr. Scharre says. “You’re missing the critical time period for treatment.”

The key to the SAGE test is that the patient takes it on his or her own, then brings it to a physician to have it scored. A primary care provider is not responsible for knowing how to administer the test, as is the case with other cognitive tests.

Dr. Scharre deliberately wanted the test to be accessible to everyone, and the simplicity of the paper-and-pen format was central to that.

“What we had was not working. We needed something that was practical,” he says. “The reason self-administered tests had not been done before was that it is very hard to assess memory on a self-administered test. I had to figure out a way to test memory. I also had to figure out how to test for executive abilities and other tasks in a self-administered way. Pen and paper was the most practical format at the time and very portable.”

Its effectiveness is supported by evidence. A recent study followed more than 600 patients at the Center for Cognitive and Memory Disorders over eight years and found that the SAGE test accurately identified patients with mild cognitive impairment who eventually progressed to a dementia diagnosis at least six months earlier than the most commonly used testing method.

New developments could further improve the test’s performance. Dr. Scharre’s team has developed a digital version of the test, which offers several tangible improvements. For instance, researchers can now time how long a patient needed to complete the test and evaluate which questions took longer, which might offer a glimpse into which parts of a patient’s brain are struggling. Eventually, this information will become part of a patient’s medical record, ensuring that they receive proper care.

‘He just has this way with people’

Ellie Halter remembers the drives more than a decade ago from Ottoville, a tiny village in northwest Ohio. In the passenger seat, her mother Pauline, a patient of Dr. Scharre’s who had advanced Alzheimer’s, had a specific routine she would use on the hour-and-a-half drive to Columbus.

“The thing I remember the most is that Mom so wanted to impress Dr. Scharre, she’d want to practice,” Halter says. “ ‘OK, my siblings’ names are ...’ and she would go through those. How many kids she had.

“She would practice so she could impress him. It meant that much to her. Everything that he said, she would try and do.”

Halter’s recollections of the care that Dr. Scharre provided her mother, who died in 2010, extend beyond the clinical trial she participated in and the treatment he prescribed for her. She talks often of how compassionate he is not only to his patients, but to the caregivers who help them every day.

“A lot of times, Alzheimer’s patients will see somebody when there’s nobody there, or maybe they think there is a fire,” Halter says. “Dr. Scharre says, ‘What do you gain by fighting with that patient?’ If you tell that patient ‘Sure, that’s Charlie,’ or ‘I’ll go put the fire out,’ you let them have their peace.

“I have told that to so many people that are struggling, and they stop and think. So many people have said maybe that’s the best advice you could give a caregiver.”

Dr. Ramamurthy, who met Dr. Scharre in 2013 during his residency in internal medicine and now works alongside him as a neurologist at the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, says Dr. Scharre was integral in his decision to go into the field.

“My residency director told me to think about what kind of patient population I wanted to work with,” Dr. Ramamurthy says. “My experiences with Dr. Scharre shaped that. He gets along really well with his patients and enjoys talking to them. Clearly, I could see something was good about him.”

As Halter says, “He just has this way with people.”

An incurable disease … or is it?

For all the advancements that have been made in the treatment of dementia, it is sobering to remember that it has no cure. But Dr. Scharre is optimistic that can change.

“There is no doubt in my mind that we will have great treatments, delay the disease, and eventually we will get to cures,” he says. “We have already made huge progress in the number of years I’ve been here. We’ve helped people all over the world.”

“What drives me is the passion of helping these patients and families and caregivers. Being a steady guide through their journey through dementia is very rewarding.”