Surgeon blazes a trail for women and people of color in urology

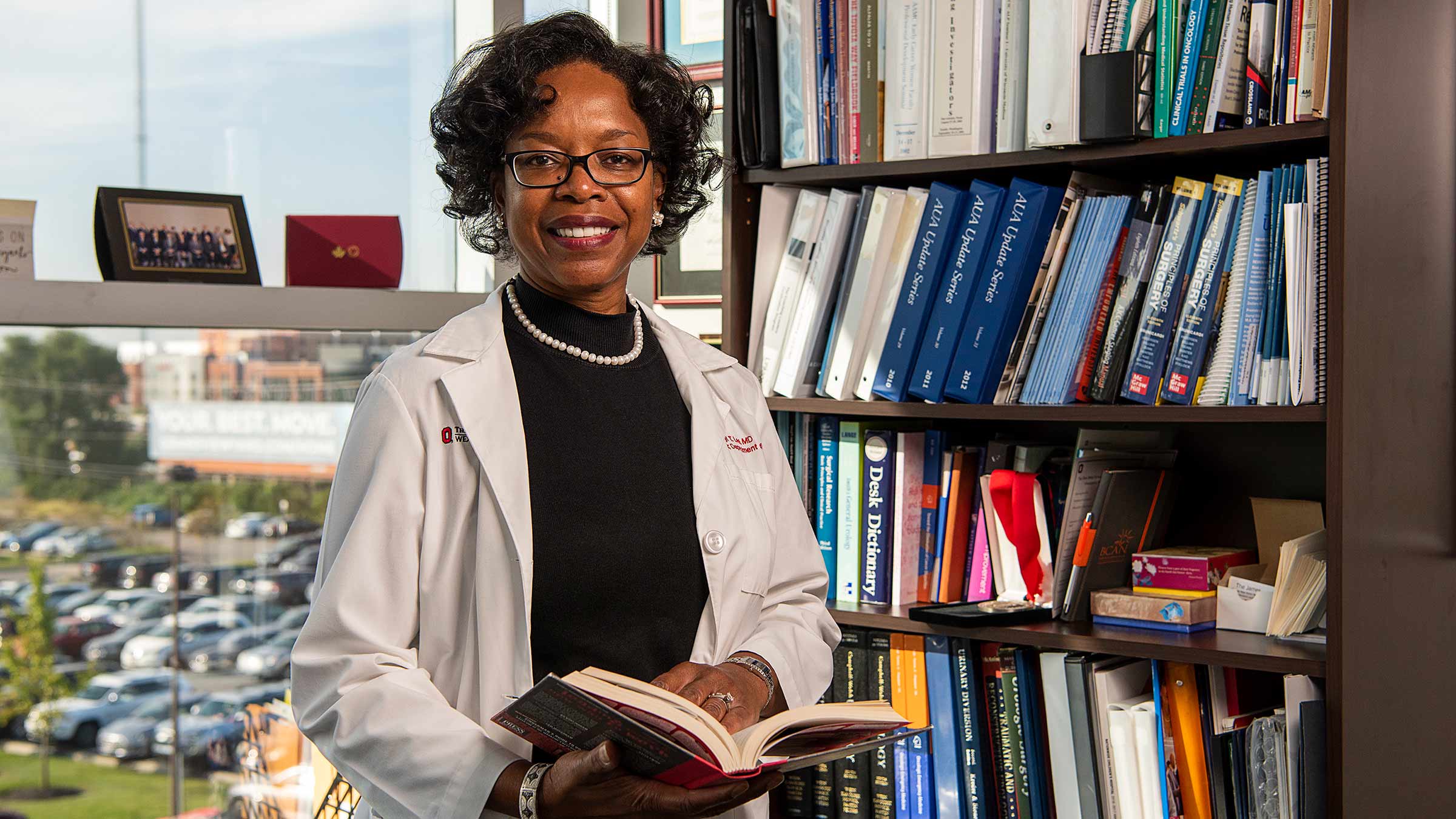

Cheryl Lee, MD, is the first Black female chair of a urology department. She’s working to ensure she won’t be the last.

On the wall outside the office of Cheryl Lee, MD, hangs a series of photos of her predecessors, all former leaders of the Department of Urology at The Ohio State University College of Medicine.

Some go as far back as the era of only black and white photos. Portrait after portrait depicts a white man. Then there’s Dr. Lee, the newest photo in the lineup: a Black woman wearing her signature pearl-cluster earrings and pearl necklace.

When she became the Dorothy M. Davis Chair in Cancer Research in 2016, Dr. Lee was the first Black woman in the country to lead a urology department. She’s a bladder cancer specialist and a surgeon in a field with few women, and even fewer Black Americans. She’s worked to change that landscape. Mentoring trainees, medical students and junior faculty members, Dr. Lee is hoping to inspire others, particularly people of color and women, to follow her into leadership roles.

People often ask her what it’s like being in her position. She’s honored, she tells them.

“But I don’t wake up every morning and think, ‘I’m a woman of color leading a department.’ I’m just trying to advance my department. If I can achieve that and also open doors for women and people of color, then I’ve hit a home run.”

Increasing diversity in urology

While Dr. Lee hasn’t always been comfortable being the outlier, she says she’s never second-guessed her decision to pursue urology. It’s a medical specialty with few women, and a small, but growing number of Black Americans, Hispanics and those who, like Dr. Lee, were the first in their families to attend medical school. The field is more diverse than when Dr. Lee began working as a urologist 22 years ago, and she hopes to have contributed to that trend.

Dr. Lee has advocated for training on unconscious bias to encourage a diverse body of medical students and urologists across the country. At Ohio State, she’s helped launch programs for women and people of color in medical school to expose them to urology, and for undergraduates to shadow physicians and participate in research.

During her two decades working with the American Urological Association, Dr. Lee has made it a priority to attract more people of color to the field.

“She’s been pushing the envelope in a professional, consistent and respectful way,” says Emilie Johnson, MD, MPH, a pediatric urologist and associate professor at the Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

Dr. Johnson considers Dr. Lee a trailblazer, unafraid to challenge the status quo and generous in her support of the next generation of doctors, having trained over 150 resident physicians and fellows.

“She helps push people forward and propel them to opportunities they didn’t know they were qualified for — or even available to them,” says Dr. Johnson.

Dr. Johnson was in medical school at the University of Michigan when Dr. Lee was on faculty there. Today, she typically only runs into Dr. Lee at conferences. And every time, she jockeys for a spot in the crowd of Dr. Lee’s mentees.

“When you walk down the hall at a conference, she’s the one everyone wants to see.”

Addressing health inequities in urology

A key ambition of Dr. Lee’s has been to improve the conditions that can keep some people from living long, healthy lives, including poverty, digital literacy gaps and racism.

“If you’re caring for patients who are from challenged circumstances, reducing barriers to health is what you have to do to deliver care. If you don’t, no one else will,” Dr. Lee says.

Although white Americans are twice as likely to have bladder cancer as Black Americans, Black patients are far less likely to survive. They tend to be diagnosed at a later stage of the disease than white patients. Dr. Lee has studied why that might be and how to increase the odds of Black patients having better results trying to overcome bladder cancer.

Compared to other cancers, bladder cancer has a relatively high rate of survival: 77% of patients, on average, survive within five years of being diagnosed. But bladder cancer also has a high rate of reoccurrence, which makes follow-up appointments and screenings all the more critical.

To assist bladder cancer survivors, Dr. Lee helped create a model care plan that includes a record of their treatment history as well as future checkups and screenings. Much of that work she did with Nihal Mohamed, PhD, an associate professor of psychology and director of patient education and behavioral research in the Department of Urology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

When Dr. Mohamed approached her in 2014 to collaborate, Dr. Lee immediately saw the importance of mental health professionals in assisting bladder cancer survivors, Dr. Mohamed says. She was open to mentoring Dr. Mohamed, and years later, many of Dr. Mohamed’s students.

“She’s a role model for many of us who are identified as minorities,” Dr. Mohamed says. “She gives us hope that we can do it, in spite of any challenges or barriers we may encounter.”

A desire to have immediate impact leads to a career in surgery

Though she found her niche in urology, Dr. Lee’s path to the field was hardly a straight line.

As a child, she thought she’d become a psychologist or psychiatrist. She liked listening to people’s problems and coming up with advice. Growing up watching “The Bob Newhart Show,” she thought: I could do that.

Her father, who immigrated to the United States from Trinidad, had something else in mind. He wanted her to be a lawyer. But being strong-minded, she was not easily swayed by even her father’s ambitions for her.

“I was pretty confident in my own ideas,” she says.

And yet, in medical school, shadowing psychiatrists changed her career goals. Sometimes helping resolve problems for psychiatric patients took years. She wanted to see a more immediate impact.

Fixing problems and getting quicker results attracted her to surgery. So after medical school, Dr. Lee went on to study surgery, a rigorous path few of her female classmates were choosing at the time.

“Look to your left and your right,” Dr. Lee remembers a professor telling the class. “Many of the people you see will drop out by the end of the fourth year.”

The remark didn’t intimidate her.

“I wasn’t afraid to work hard and, for me, that led to success.”

Finding urology

Throughout her residency at the University of Michigan, she clicked with urologist on staff. From there, Dr. Lee, a native of New York, moved back to her home state for a fellowship in urologic oncology at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

As a urologist, her patients have been mostly white men. The fourth most common cancer in men, bladder cancer is far less common in women. And it’s more common among white men than men of color.

When she started out in the field, some patients weren’t used to seeing a woman in urology — certainly not a Black woman.

As a young surgeon, Dr. Lee, at times, had an obstacle to overcome, says James Montie, MD, Professor Emeritus of urology at the University of Michigan.

“She had to demonstrate the confidence in herself to be able to transmit that confidence to the patients so they might trust her. She was able to do that quite well,” Dr. Montie says.

“That’s a hard thing for any young surgeon to do, and particularly for a young Black woman.”

Skilled at communicating with patients in a down-to-earth way, she also was adept at dealing with the unexpected, Dr. Montie says.

“She showed a great deal of composure and didn’t get riled by situations or wilt under pressure.”

Early on in her career, she led clinics at a Veterans Administration center where sometimes a patient might express their skepticism with derogatory comments about whether she, as a woman, knew what she was doing.

“I discharged a couple of patients and told them why,” she says.

Those experiences were the exception. In her many years as a physician, Dr. Lee says she’s had very few moments of facing explicit bias because of her race or gender. If people had subtle biases, she looked past those, staying focused on the work she needed to get done.

Supporting patients with bladder cancers

Part of what attracted Dr. Lee to treating bladder cancer was that her patients really needed support. Many struggled financially. They were elderly, some without much formal education. Several had been exposed to chemicals at their jobs, the second leading cause of bladder cancer in the United States, just behind smoking.

“They were patients who were deeply affected by their condition and needed someone to advocate for them,” Dr. Lee says. “I knew I was making a difference.”

Practicing physicians across the country appreciate Dr. Lee’s expertise and her approach. Year after year since 2008, Dr. Lee has been named to the Castle Connolly list of “America’s Top Doctors.”

Open to the possibilities

In a career with so many accolades and high points, Dr. Lee only regrets not having enough time to pursue her interests beyond medicine: art, music and writing poetry, which she hopes to turn into song lyrics.

“It’s probably too late to become a music producer, but I don’t know,” she says with a laugh.

She took piano lessons growing up, and though she didn’t continue, she’s often listening to music, even while performing surgery: Jimi Hendrix. The Eagles. Motown. Classical. She likes variety.

And yet some things with Dr. Lee stay the same. Whether she’s seeing patients or meeting with colleagues, she’s usually wearing the same pearl necklace and pearl-cluster earrings. It’s a habit that has stuck for decades. She’s not exactly sure why.

Recently, more people have taken notice. A patient asked her if her pearls had anything to do with U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris, whose pearls are a symbol of her university sorority, one of the nation’s oldest black sororities.

Just a coincidence, Dr. Lee told the patient.

“I’ve been wearing these pearls for 20 years,” she says.

Which seems a fitting response for a woman who’s not so interested in following what’s popular, but is more apt to choose the uncommon path.

Accurate, early cancer diagnosis matters

The James Cancer Diagnostic Center gives patients direct, expedited access to diagnostic testing and consultation with Ohio State cancer experts.

Schedule an appointment today