Uncovering hidden health risks through genetic screening

A surprising result from an Ohio State genetics research study has given Michelle Wessel a new plan to protect her health.

Michelle Wessel noticed the first lump when she was 38.

Her left arm brushed across her chest. Something felt hard under the skin.

A little over a year after being treated for breast cancer, she found another lump, this time under her arm. Stage 4.

“I woke up every morning thinking I was dying,” says Wessel, now 52.

Drained from the treatments and the cancer itself, she could hardly get out of bed to get to the bathroom. For months, she didn’t venture outside, not even to the front porch.

“I don’t want to go back there,” she says, waving both hands over her shoulders, as if pushing away that period in her life about a decade ago when she was treated for and overcame cancer.

In January 2025, Wessel received an email asking her if she wanted to be part of a research study that examines people’s DNA for risk of certain cancers and an inherited risk for high cholesterol. The Ohio State Genomic Health study is being done by The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in partnership with Helix, a genomics research company, to better understand how genes affect health.

Wessel signed up for the study right away. Already, she knew she had inherited a genetic variant, a change in the BRCA1 gene, which normally prevents breast and other cancers. That variant puts her at high risk of developing breast, ovarian, pancreatic and other cancers.

Years earlier, while being treated for breast cancer, Wessel was tested for BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene variants.

“I wasn’t surprised, not in the slightest,” she says.

However, Wessel was surprised when she opened an email from the Ohio State Genomic Health study in February and read the results: She had inherited a second genetic variant, one that causes Lynch syndrome. The condition puts her at an above-average risk for various cancers — colon, rectal, endometrial as well as others.

“I was shocked,” she says. “I was thinking, ‘Really? Another one? Surely, I can’t be that unlucky.’”

Zeroing in on key genetic risk markers

The odds are slim. On average, one in 200 people have a variant in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes. Typically, the two genes prevent tumors. But a change in either can remove that protection, creating higher-than-normal risk for breast, ovarian, prostate, pancreatic and other cancers.

Even lower odds: One in 279 people in the United States have Lynch syndrome, a condition caused by a genetic variant passed down from one or both parents.

Anyone who participates in the Ohio State Genomic Health study will have their DNA analyzed for:

- Lynch syndrome, the most common cause of hereditary colorectal (colon) cancer

- BRCA variants, which are linked to hereditary breast and ovarian cancer

- Inherited high cholesterol, also called familial hypercholesterolemia

“We’re trying to help prevent cancer and other diseases and not be blindsided by them,” says Ilene Fox-Comeras, BSN, RN, a clinical research specialist and one of the coordinators of the Ohio State Genomic Health study.

An estimated 1 to 2% of people who join the study are expected to have at least one of the gene variants. Wessel has two.

“If you find out you’re at risk for certain diseases, you can do something about it,” Fox-Comeras says. “You can start screenings for it.”

Taking action for your health

If someone learns they’re at high risk of colon or rectal cancer, like Wessel did, they can begin getting cancer screenings immediately, rather than waiting until they’re 45. They can have more frequent colonoscopies — every one to two years instead of every 10 years for the average person.

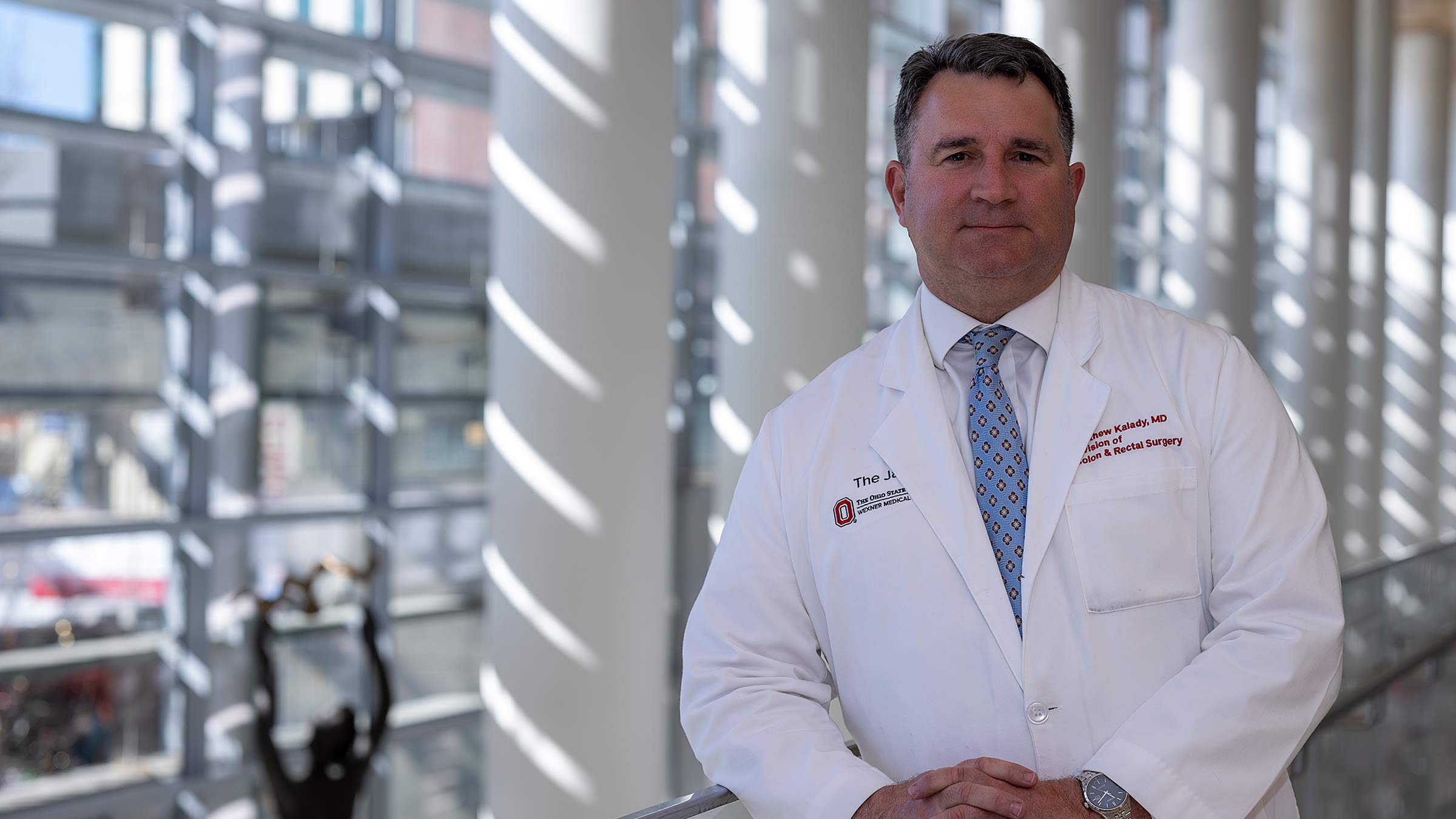

Sometimes cancer, including colon or rectal cancer, can develop without any symptoms until it’s far along, says Matthew Kalady, MD, a colorectal surgeon at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute (OSUCCC – James).

“People in their 20s or 30s with Lynch syndrome can have colorectal cancer, at a time when cancer would not be expected,” Dr. Kalady says.

“If you aren’t looking for these cancers through screening tests, they might not be detected until it’s too late to effectively treat them.”

If you have a BRCA gene variant, you can also take steps to detect breast cancer early on, through earlier and more frequent mammograms and other screenings. That’s when it’s the most treatable.

“We’re identifying people who have no idea they have a certain mutation. Some of them were shocked, but they wanted to know,” Fox-Comeras says about the study.

Over four years, the Ohio State Genomic Health Study will enroll up to 100,000 people. The DNA analyses of their blood samples will not only reveal high-risk genes but also may, in the future, help identify genetic patterns that put people at lower risk for certain conditions, says Andrew Thomas, MD, MBA, chief clinical officer for the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center and clinical professor of Internal Medicine at The Ohio State University College of Medicine.

“This could reduce someone’s fear about developing a condition, and may cut health care costs by eliminating or delaying some screening or testing in lower-risk patients.”

‘I want a heads up’

Wessel calls herself a country girl. In the small town of Portsmouth, Ohio, she grew up roaming barefoot through the surrounding woods, the middle child with two sisters, each three years apart.

Among her relatives, some had cancer, but no one had any of the cancers associated with Lynch syndrome. There was no colon, rectal or endometrial cancer. So how could she have gotten Lynch syndrome, she wondered.

At the same time Wessel was anxious about having Lynch syndrome, she was also glad to at least be aware of it.

“Some people don’t want to know,” she says. “I want a heads up so I can prepare.”

Each of Wessel’s two genetic variants came from one or both of her parents. And she has a 50% chance of having passed one or both along to her only child, Bethany, who’s 26.

Each of Wessel’s two genetic variants came from one or both of her parents. And she has a 50% chance of having passed one or both along to her only child, Bethany, who’s 26.

“The thought of her having it terrifies me,” she says.

And yet, Wessel also realizes that knowing her own risks for cancer enables her to support her daughter in trying to prevent it.

Why genes aren’t destiny

Sometimes people struggle with knowing how to tell their relatives or children that they, too, might have the same genetic variant that puts them at risk of a disease, says Rachel Pearlman, MS, a genetic counselor at the OSUCCC – James.

“I always tell my patients, ‘You can’t change the genes you were born with, but you can use the information in a way to keep yourself as healthy as possible and help to keep your family members healthy by telling them as well.’”

Anyone who receives a genetic screening can offer their relatives “the gift of information,” so that they, too, can be tested, Pearlman says.

“They may not have otherwise known.”

When people find out they have an inherited risk for cancer, they might assume they’re going to get cancer, Fox-Comeras says.

“‘No,’ I tell them. ‘This demonstrates you have an increased risk for cancer compared to the normal population. But it doesn’t mean you will automatically get cancer.’”

Regular exercise, a healthy diet, and avoiding alcohol and smoking all influence whether someone develops cancer or another disease, even if they have an inherited genetic risk for those diseases, Fox-Comeras says.

From adversity to adventure

Though she’s had breast cancer three times, Wessel doesn’t worry about the specter of cancer or early death. Around the time she was treated for Stage 4 breast cancer, that’s all she thought about.

“I spent too much time thinking about my health and cancer. I can’t let that be the dictator of my life. I’m going to do everything I can. It’s not going to run my life. I just can’t let it,” Wessel says.

After her third time with breast cancer, she had a mastectomy. She’s also had a hysterectomy. Every one to two years, Wessel plans to get a colonoscopy and other screenings, including for skin cancer.

Sometime after discovering the first lump, Wessel realized there was so much she wanted to do in her life, so much more of the country and the world she hadn’t yet seen.

Not long after finishing chemotherapy for Stage 4 breast cancer, Wessel drove to California, making the trip in two days, alone, with no specific plans except to see the Pacific Ocean. A few months later, she drove back to Ohio, in a little over a day — 30 hours of driving and a lot of Red Bull and coffee.

“I had that need, that drive, that pull, to live the whole time, but I thought I had lost my opportunity.”

Two years ago, she flew to Portugal with her partner, then to Ireland with her daughter. Next, she’s hoping to take a trip to see her daughter in Tokyo, where she teaches English.

Living in the moment

Around Wessel’s right wrist is a constant reminder to her — a tattoo of a charm bracelet. Two charms have cancer ribbons: one for her father who died from lung cancer, another for her victory over breast cancer. There’s a charm of a smiling sun, representing her daughter, and a charm of the rhythmic waves of a heartbeat, a nudge to live in the moment.

“I’m lucky,” she says. “I’ve had the good and bad in my life.”

And even the bad has helped her in ways she didn’t expect. She no longer passes up chances to travel, to meet people, to go up to a stranger, even, and compliment them, knowing that just might lift their spirits. Cancer taught Wessel all of that.

Ohio State Genomic Health

A no-cost community health research program to learn if you have an inherited risk for certain cancers and a specific cause of heart disease.

Participate in research

Genetic screening protects the future of health

Join us in supporting cancer research at Ohio State.

Give today