Bridging the language barriers of foreign-born patients

A new Ohio State program connects multilingual doctors with foreign-speaking patients to increase health care access

Though she knew she needed to see a doctor, Fatima Khurram had a tough time mustering the energy to go.

The appointments were cumbersome, a triangle of her speaking in her native tongue of Urdu, an interpreter saying it in English to a doctor, then the communication wave shifting from English to Urdu, the national language of Pakistan. All the back and forth took a lot of time and exhausted Khurram. And if the interpreter was a man, Khurram was reluctant to say much. Everything seemed too personal to share. She wanted to talk to a woman, preferably a woman who understood Urdu.

After eight years of off and on searching, Khurram recently found a family practice doctor who speaks her language.

“I feel like we’re friends,” Khurram says sitting across from Taru Saigal, MD, a primary care physician at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center and clinical assistant professor of Internal Medicine at The Ohio State University College of Medicine.

Khurram smiles, her dark eyes wide and expressive just above the edges of her face mask as she explains in Urdu the connection she feels with Dr. Saigal.

“She answers my questions. She understands,” Khurram says. “That takes away a lot of my anxiety.”

Matching same-language physicians and patients builds trust, improves safety

The number of patients using interpreters at the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center has grown by about 4,000 patients during the past two years. The top demand for the free interpreter service available to any patient 24/7 has been for Spanish followed by Nepali, Arabic, Somali, American Sign Language and Mandarin.

Even with some primary care physicians speaking to patients in their native tongue, interpreters will always be needed. It’s impossible to match every patient unable to fully speak or understand English with a physician fluent in their native tongue. But a new program is beginning to bridge that gap for patients.

Last spring, Dr. Saigal, who’s fluent in four languages, launched a program linking patients with limited English with primary care doctors at the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center who speak their language. Along with Dr. Saigal, 10 other primary care doctors at Ohio State who speak more than one language fluently have been matched with patients. The physicians are fluent in Arabic, Bengali, Japanese, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Mandarin, Nepali, Punjabi, Urdu and Vietnamese.

With new primary care physicians being hired and so many multilingual physicians already on staff, the program is expected to expand.

Having a doctor fluent in a patient’s language can eliminate the need for an interpreter, making it easier for some patients to build trust with their doctors, Dr. Saigal says.

“It can be very hard for a patient to open up with an interpreter there,” she says. “Sometimes we’re having conversations about very sensitive topics. We talk about end-of-life care. We talk about menstruation. We talk about mental health. Those are very sensitive topics.”

When people can speak directly to their doctor, they’re more apt to discuss all of their symptoms and concerns, and doctors can better help them, Dr. Saigal says. If a patient doesn’t fully understand what a doctor is telling them, they’re less likely to carry out the advice and more likely to make a mistake with medication. And patients are generally less satisfied with the medical help they’re getting, Dr. Saigal says.

“It’s not just better care, it’s safer care when patients can speak to a physician in a language they fully understand,” she says. “When you reduce the communication barriers, they understand the disease plan, the medication, and they’re less likely to make emergency room visits.”

Finding and fixing the problem

Last year, during an overwhelming time caring for her young children and family members visiting from overseas, Khurram felt occasional dizziness, heart palpitations and a near-constant yearning to go back to bed.

Then, at the end of the day when she finally had the chance to sleep, she’d lay wide awake, her mind stuck on something.

After meeting with Khurram and ordering blood tests last spring, Dr. Saigal diagnosed the 36-year-old mother of four with having a severe iron deficiency and prescribed an iron infusion. Within weeks, she was sleeping better and had a lot more energy.

Since then, Khurram has met regularly with Dr. Saigal, the first doctor in the United States she’s been able to speak to in Urdu. She’s working on regulating her blood glucose levels to steer herself out of the stage of pre-diabetes.

Understanding the Pakistani culture, Dr. Saigal knows the type of food Khurram is accustomed to eating, so she can make appropriate suggestions about adjusting her diet. And Khurram trusts Dr. Saigal and feels her support, she says.

“Half of my illnesses go away just by talking to her.”

An idea born from experience

Dr. Saigal came up with the idea of linking multilingual primary care doctors with patients whose English is limited after several experiences with foreign-born patients in recent years.

In 2020, a woman in her 70s who spoke Nepali was being treated for sepsis at the medical center. She didn’t want to use the interpretative service, she told staff. They thought she might be confused: Why wouldn’t she want an interpreter to help her understand?

Speaking Nepali, Dr. Saigal approached the woman. The patient explained she had trouble hearing and couldn’t easily follow what an interpreter would tell her.

“She was completely coherent,” Dr. Saigal says.

Without an interpreter, Dr. Saigal spoke to the patient and her family, who were relieved that the doctor taking care of her could speak Nepali.

Later that day Dr. Saigal would post to her Twitter account: There is value added when patients can grieve and heal in the language shared by their providers.

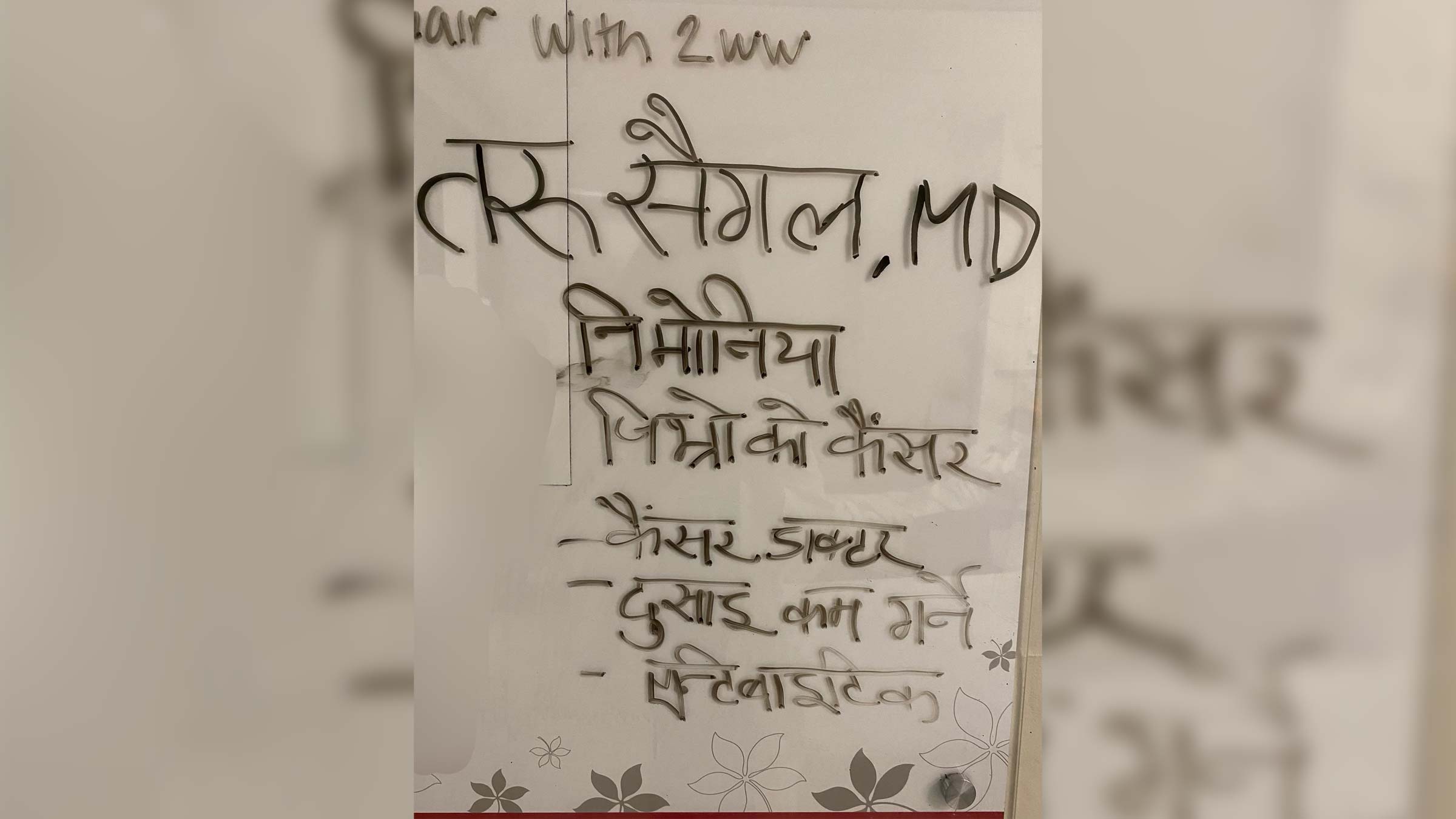

She included a photo she took of the whiteboard inside the patient’s room. There, Dr. Saigal had written in Nepali her name and credentials, the woman’s diagnosis and the treatment plan for the day.

Cherishing differences comes naturally to Dr. Saigal

Starting the program seemed a natural step for Dr. Saigal, who grew up in northern India outside of New Delhi, a region where many languages are spoken, and many religions practiced. In that swirl of cultures, her family celebrated Christmas, Diwali, the Hindu celebration of lights, as well as Eid al-Fitr, the Muslim festival marking the end of the Ramadan fast.

“That’s why this is so important to me that patients from other cultures feel like they’re getting support, the care they need,” Dr. Saigal says.

At home growing up, she spoke Hindi. In school, she was required to learn to read, write and speak in English, Hindi and Urdu, a language commonly spoken in Pakistan as well as northern India. Then in her 20s, she began medical school in Nepal. Her classes were all in English, but when she began working in the nearby villages, she had to get better at speaking and understanding Nepali. That way she wouldn’t always have to lean on her friends who were fluent in Nepali.

“They needed to understand me,” she says of her patients in Nepal. “It took three years to get there, to become fluent. But once I was there, I was able to get so much more from my patients.”

Multilingual health care brings better compliance

Dhuha Alwan, MD, MPH, a clinical assistant professor of Internal Medicine at The Ohio State College of Medicine, whose native tongue is Arabic, empathizes with patients who struggle with fully understanding or speaking English. It can be tough to learn.

One of Dr. Alwan’s patients, a woman in her 70s with diabetes and other health conditions, speaks Arabic and a little bit of English.

“I don’t think she has the capacity to learn a new language. I can’t blame her,” Dr. Alwan says. “For some people it’s not easy. We have to accommodate.”

Being able to speak directly to Dr. Alwan in her native tongue is leading the woman to better health, to lower blood sugar and cholesterol levels, Dr. Alwan says.

“She expresses her gratitude every time she comes to my clinic.”

Another one of her patients is a woman in her 30s, a mother with several children including one with special needs. She’s pressed for time, so learning English can’t be her top priority.

“It’s hard,” Dr. Alwan says. “People like her will learn in time. It will just take them longer. And in the meantime, they will benefit from this service.”

Patients at the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center wanting to transition to a primary care doctor who speaks their language can contact their current primary care physician to assist with the transition. Foreign-language speaking patients not yet seeing a medical center primary care doctor can seek one who speaks their language by calling 614-293-5123.