One of the nation’s largest living kidney donation chains brings waves of hope

Complex chain of surgeries over two days gives 10 kidney recipients a new life, makes way for others to get closer to transplantation.

The name of it alone sounds daunting: A 10-way paired kidney transplant chain.

What does it mean? In short, 10 healthy people each donated a kidney to someone they’d never met, saving that person’s life.

It was the largest such operation in the history of The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, and one of the largest single-institution transplant chains ever performed in the United States.

The undertaking was massive: two days, seven transplant surgeons, 18 hours in operating rooms, 20 patients, 2,207 instruments and untold thousands of hours planning by the hundreds of medical center staffers involved. And until the last surgery was complete on Dec. 17, the medical team held its breath knowing that any one donor or recipient could get sick or injured, and the entire chain would be disrupted.

But what is a “kidney transplant chain”? Why did these people all donate? And how did it all happen?

Let’s explain.

What is a kidney transplant chain?

A kidney transplant chain is a sequence of surgeries to deliver organs from healthy, living donors to people experiencing kidney failure. The point is to help as many people as possible. The problem that a chain solves is one of compatibility.

When a patient reaches the transplant list, their friends, family members and loved ones commonly start the process to see if they can be a donor for that person.

But oftentimes, it doesn’t work out. A complex process of blood and tissue testing takes place to ensure that donor and recipient are a match. This helps maximize the likelihood that the recipient’s body will not reject the new organ. Matches can be hard to come by.

And that means that, in many cases, you end up with a patient who is awaiting a kidney and a willing donor who didn’t match with their intended recipient.

A kidney transplant chain creates those matches by allowing donors to give to recipients unknown to them. In exchange, their loved one receives a kidney from a donor previously unknown to them.

Why do kidney transplant chains matter?

Kidney transplant chains have two major benefits. For the 10 recipients at Ohio State, new lives began for them right away. Also, moving 10 people off the waiting list at once means that everyone else on the list has a better shot at getting the next organ that becomes available for transplant.

In this case, the clinical origin of the chain started with Mike Lange, BSN, RN, PCCN.

Lange is a living donor transplant coordinator at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Transplant Center. Back in October, Samantha Fledderjohann had come forward to donate a kidney, and she didn’t have anyone in mind for it. In strict medical language, these folks are called “non-directed donors,” but around the transplant center, you’re just as likely to hear them referred to as “heroes.”

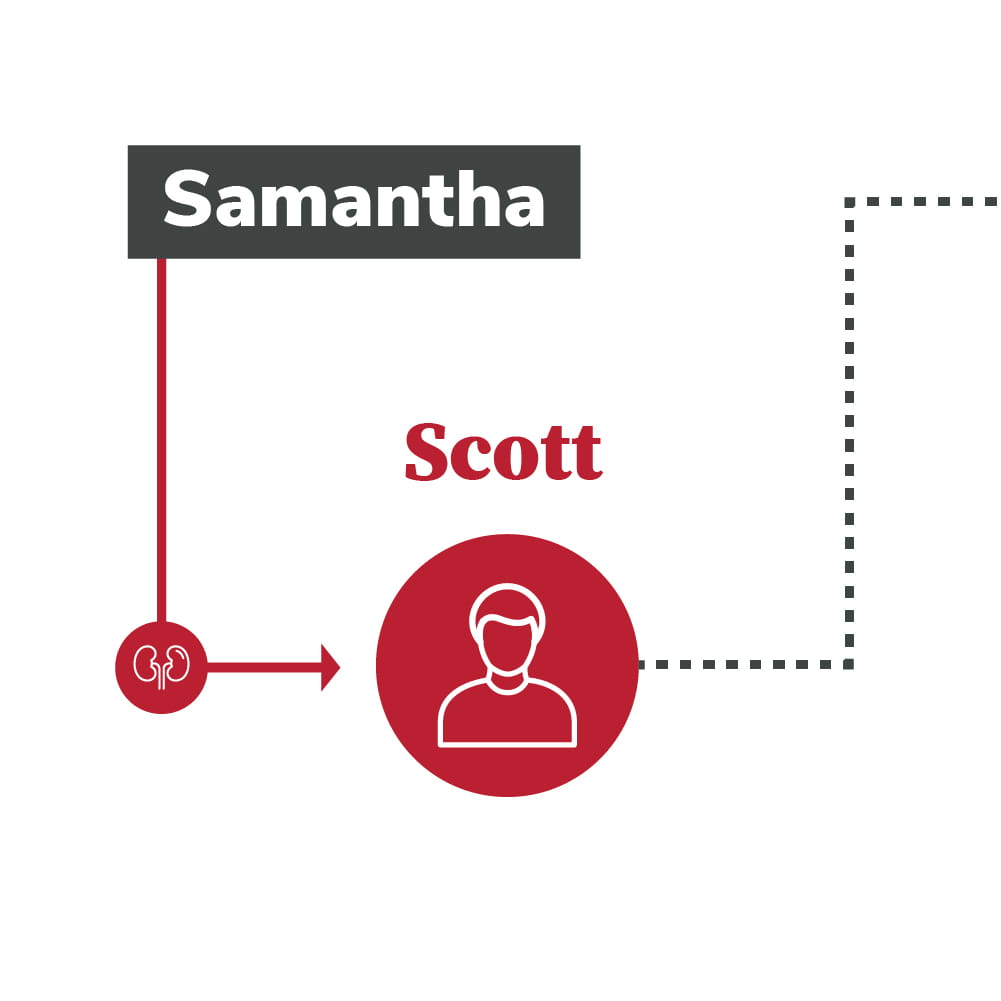

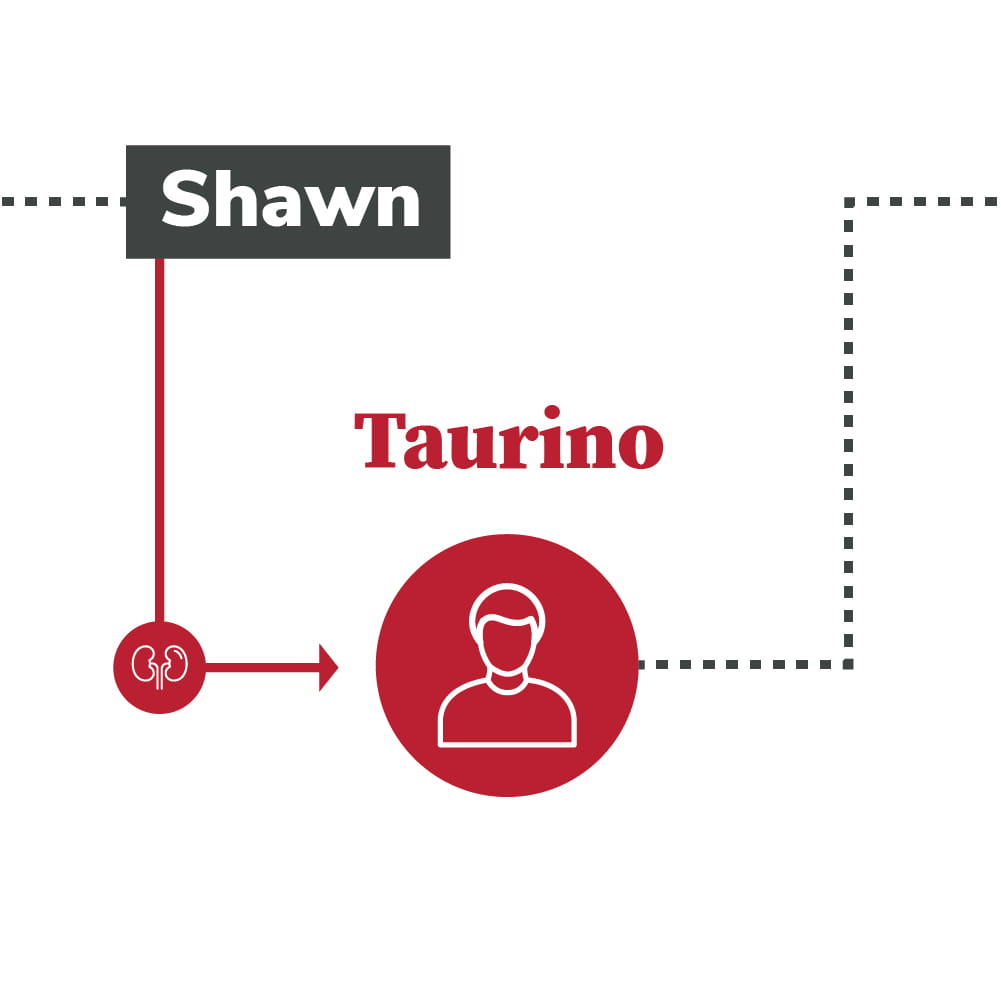

Samantha had asked to proceed with the surgery in mid-December, so Lange started looking at the list of people awaiting transplants, and a picture formed. He found Scott Humes, whose brother-in-law Shawn Carnahan had a kidney ready to donate. The two weren’t a match, though, so Scott got Samantha’s kidney, and Shawn’s went to another recipient that Lange matched him to through the list.

The matches just kept going like that, a type of “pay it forward” scenario where donors gave on behalf of kidney failure patients they’re close to, and their loved ones received a matched kidney from someone they hadn’t met. Eventually, he had 20 people total.

Anatomy of a kidney donation chain

Samantha donated to Scott.

Shawn donated to Taurino.

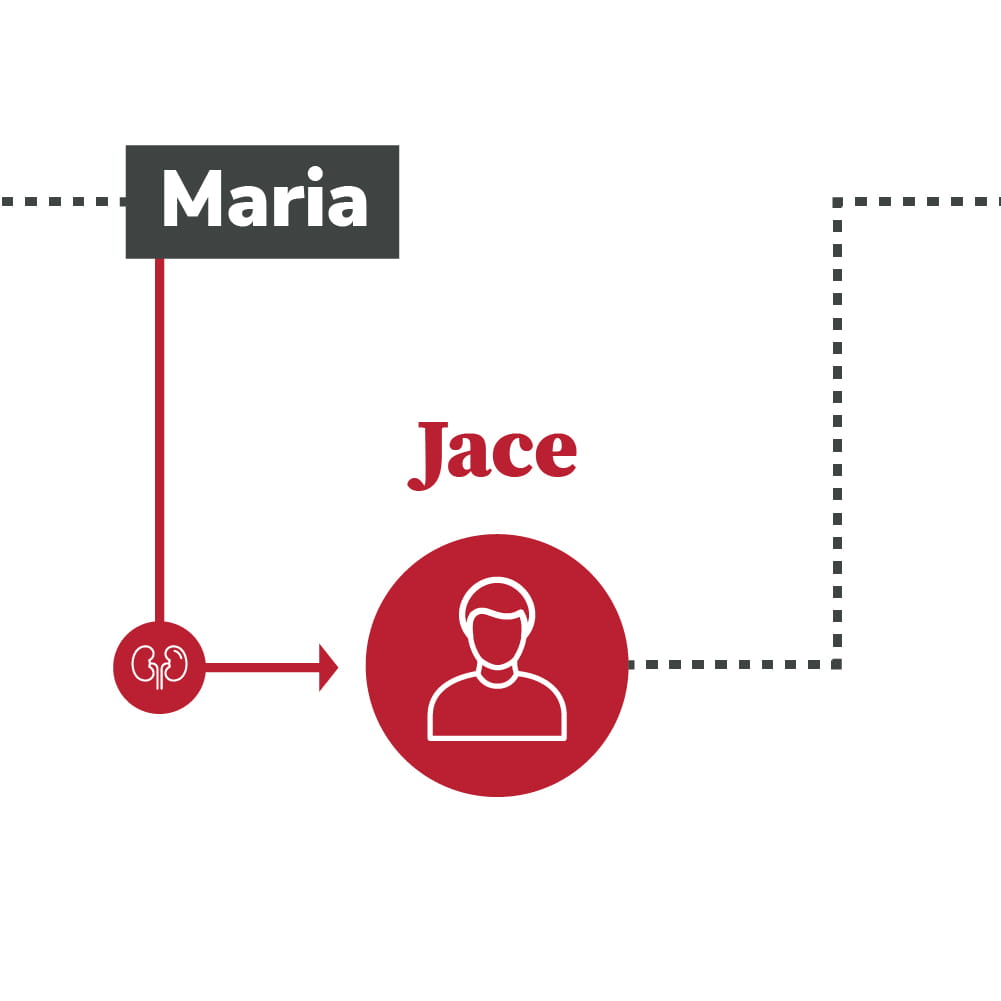

Maria donated to Jace.

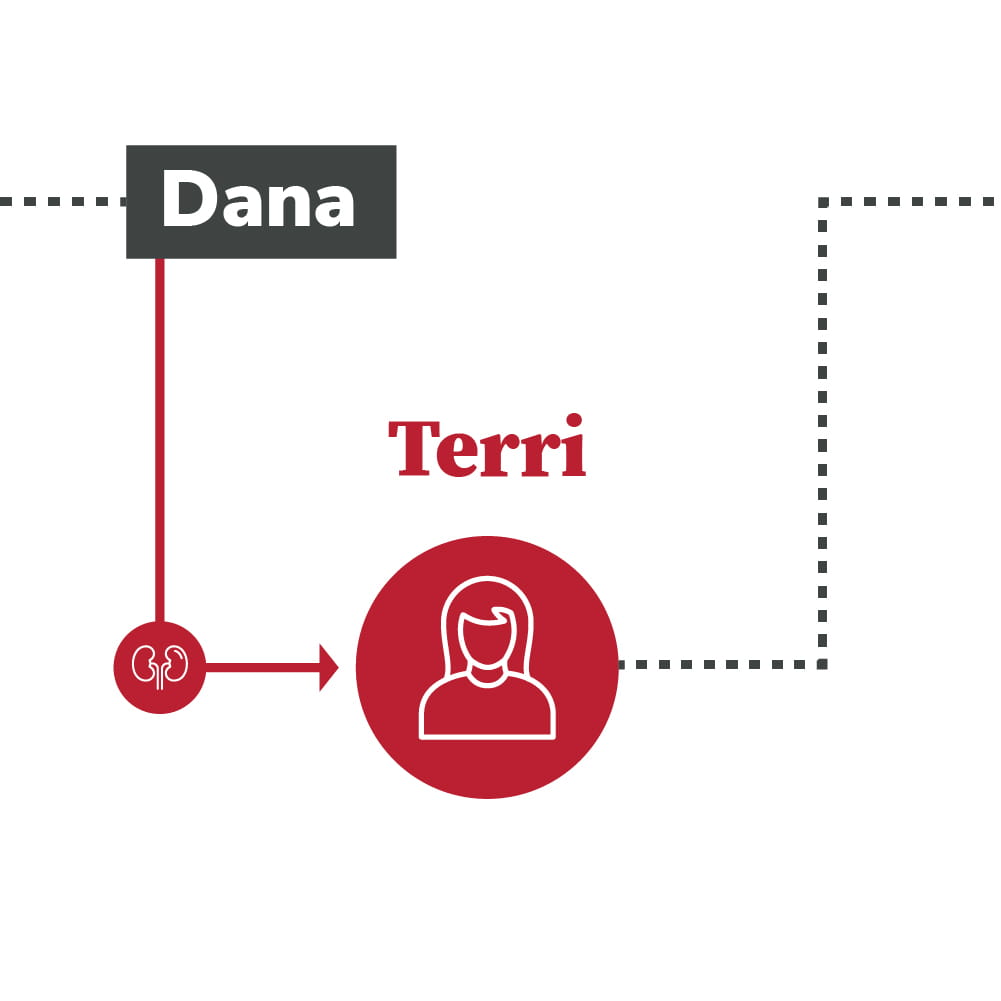

Dana donated to Terri.

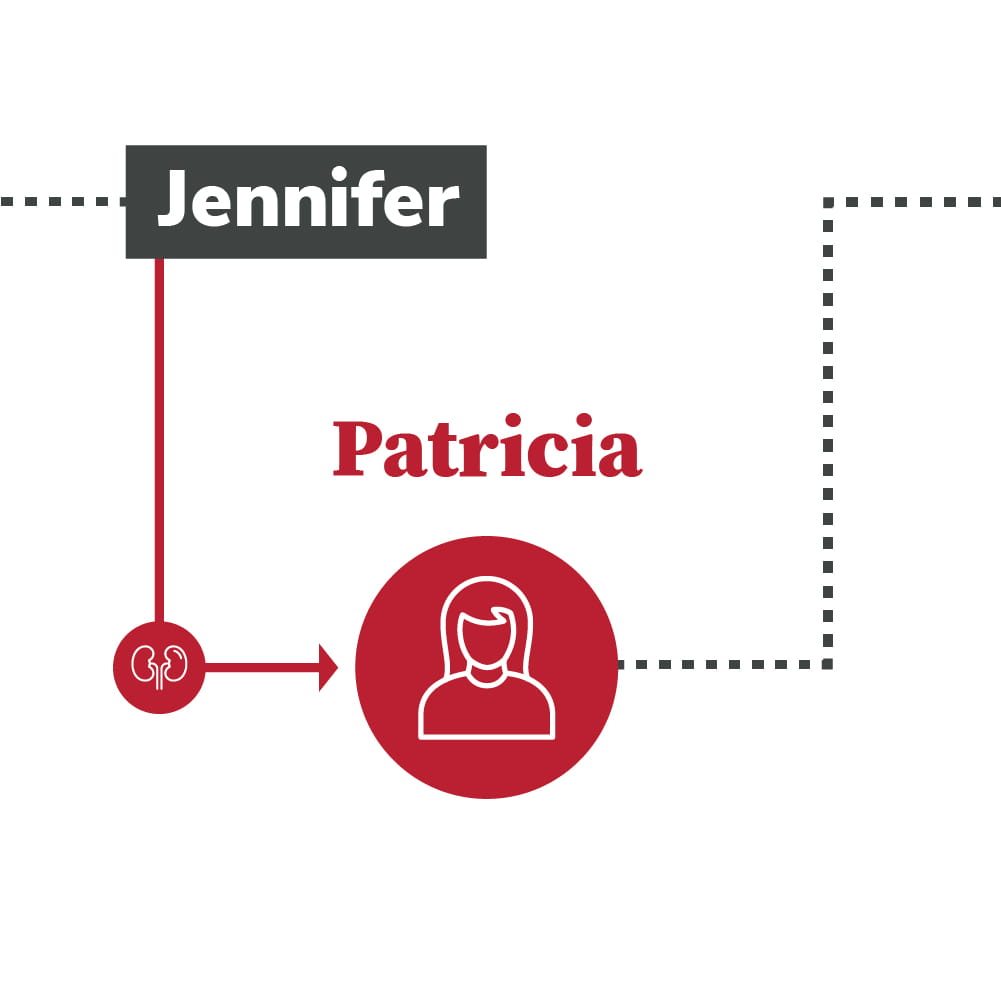

Jennifer donated to Patricia.

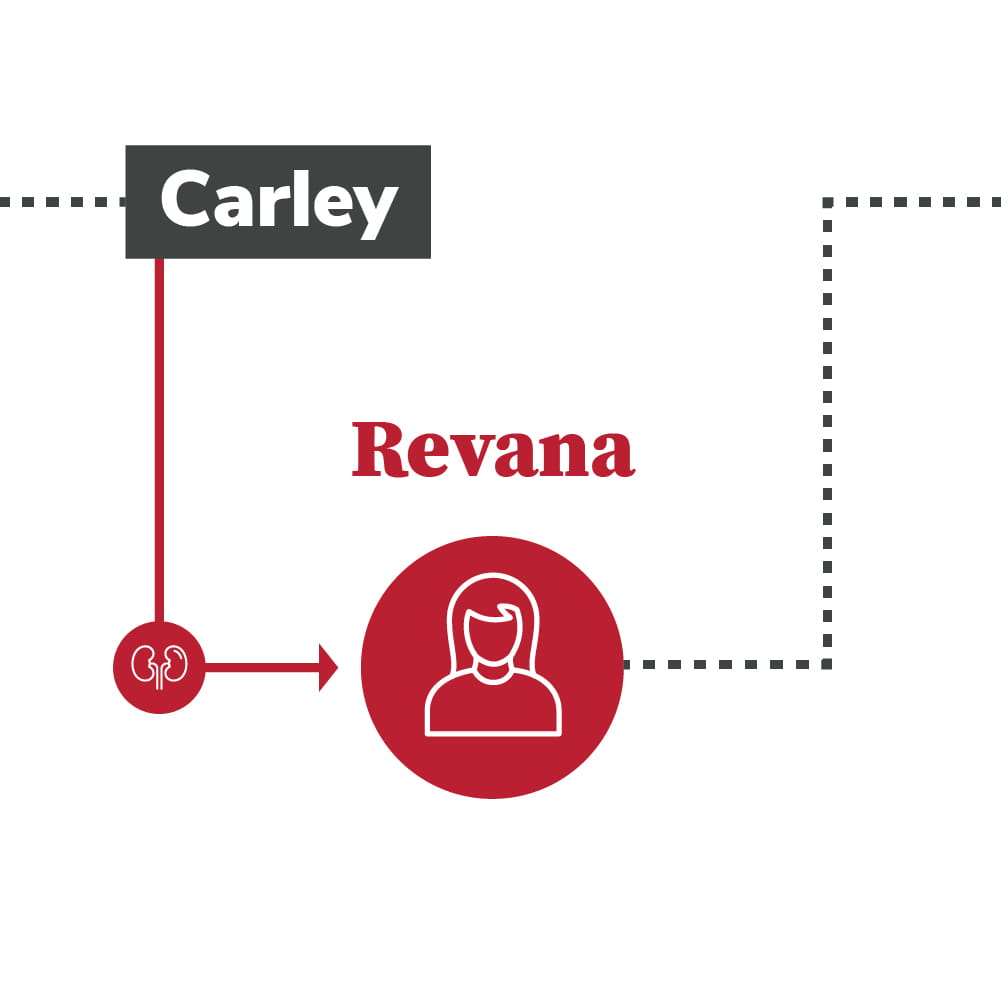

Carley donated to Revana.

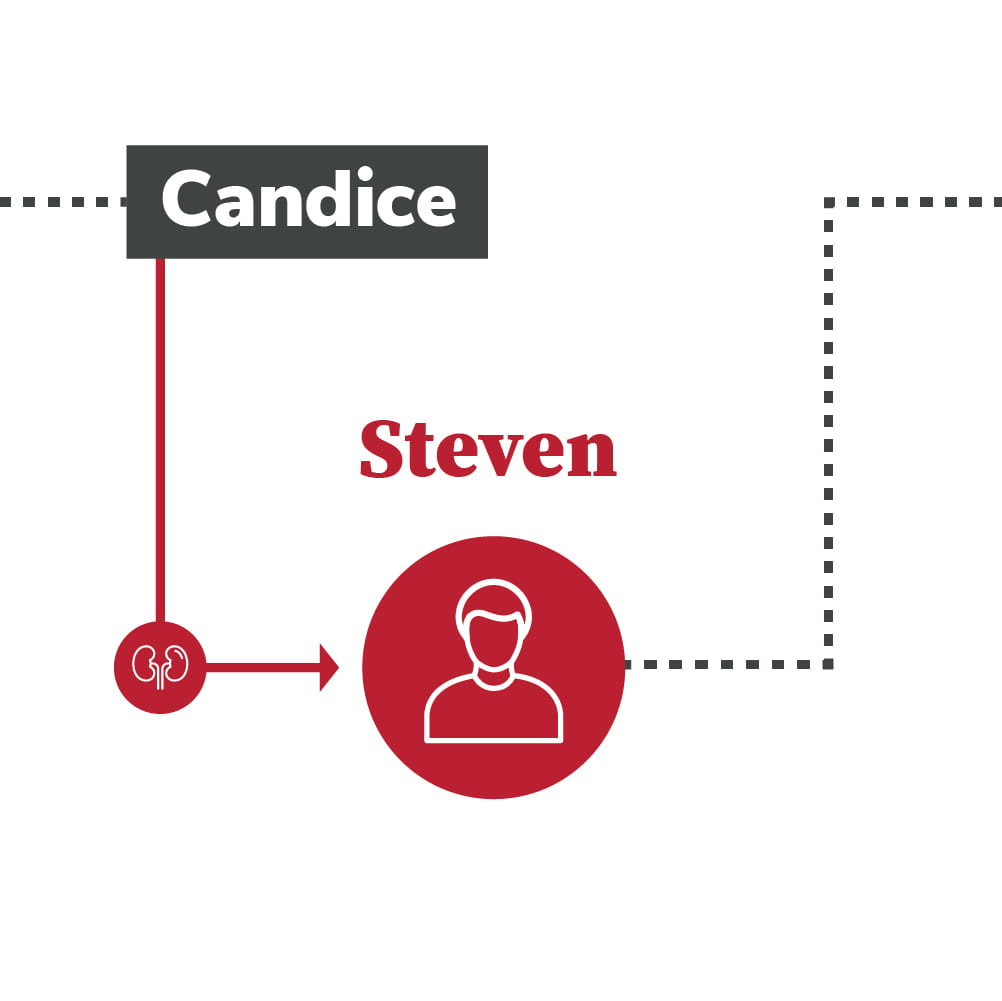

Candice donated to Steven.

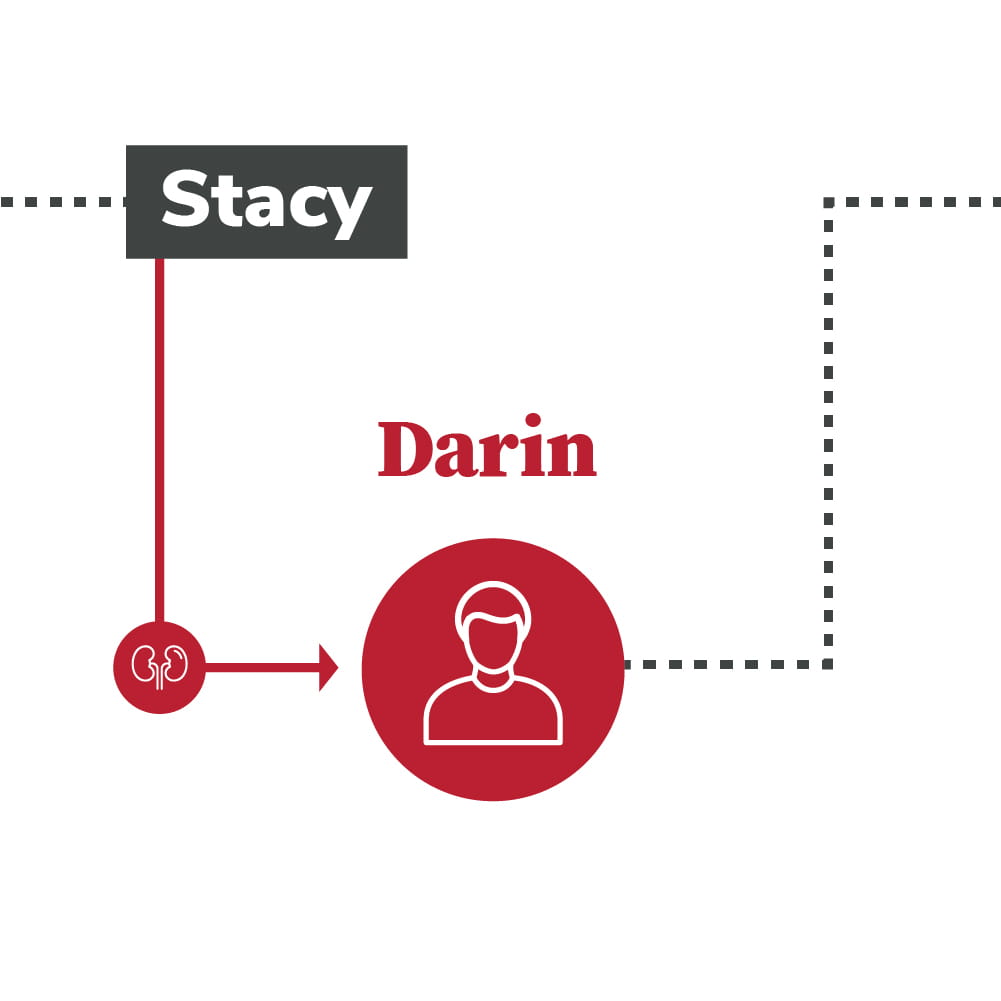

Stacy donated to Darin.

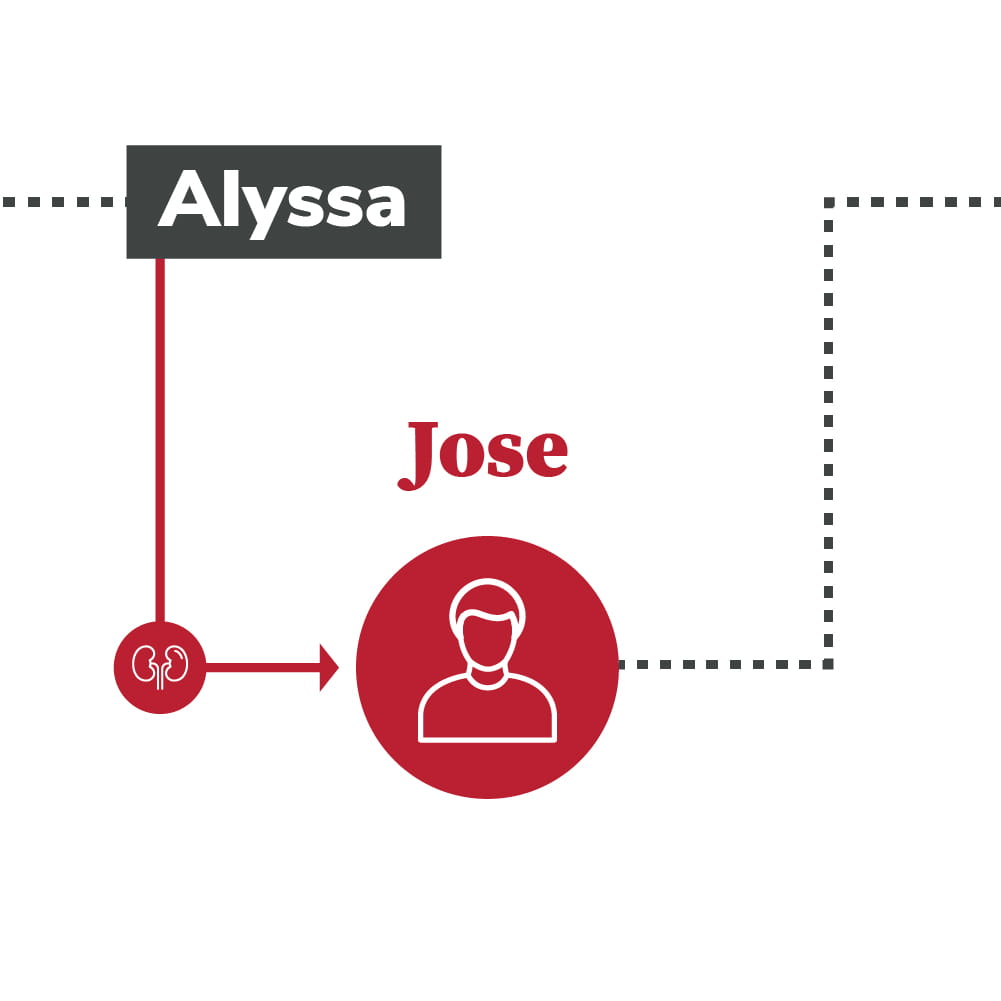

Alyssa donated to Jose.

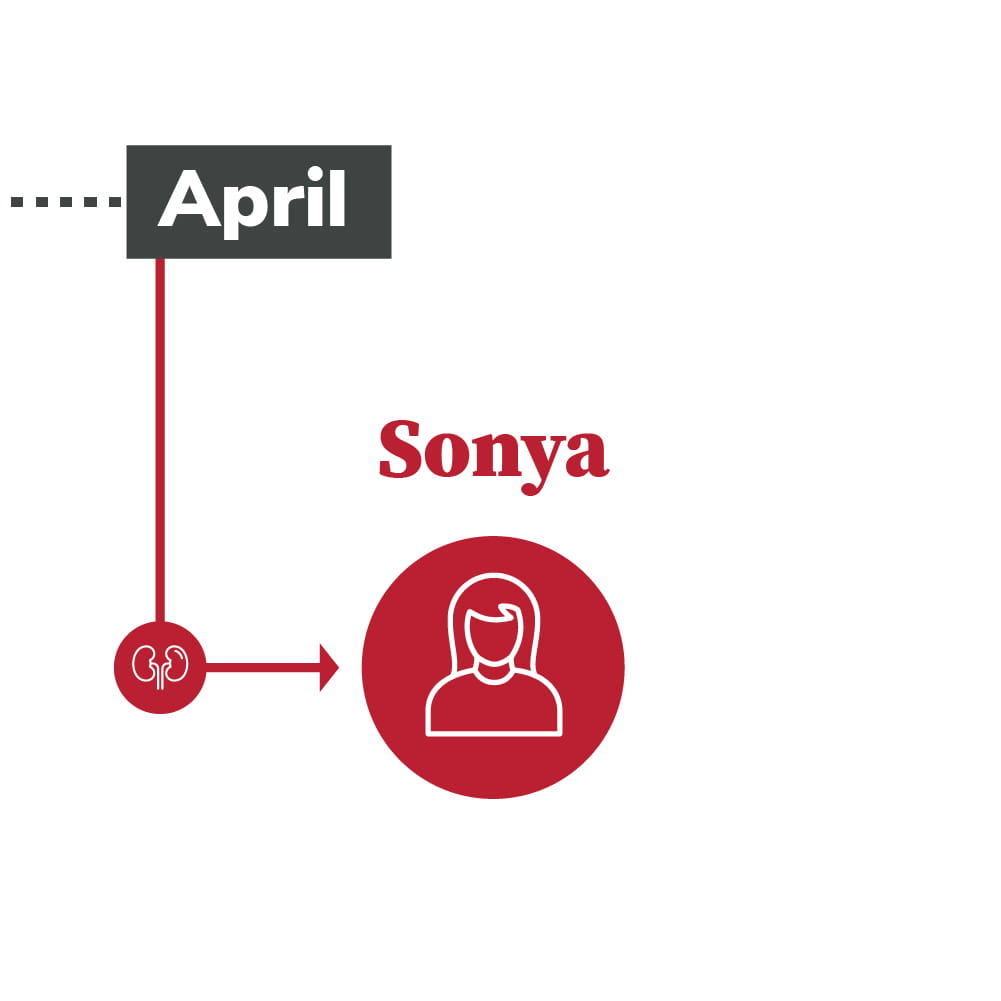

April donated to Sonya.

Bewildered and overjoyed, Lange had a colleague look the plan over to make sure he wasn’t missing something.

“I told her, ‘This will be something we probably won’t typically see, and it’s mind-boggling to me right now that it actually could work,’” Lange recalls.

“Once you have a non-directed donor, we try and look at every opportunity we can and how many people we can impact. Why not try to get as many people off the list and benefit from this one person? It was like a cascade.”

What makes a kidney transplant chain work?

Once the matches are found, an enormous amount of work begins.

Transplant coordinators contact all the donors and recipients to ensure everyone is available and to schedule the surgeries. Recipients and donors go through final checks to ensure everyone is healthy and ready for surgery.

Space in four operating rooms needs to be reserved — in this case, kidneys are removed from a donor and taken to an adjacent operating room, where they’re immediately transplanted into the recipient. Nurses, residents and other medical staff need to be in place, supplies need to be ready.

Jennifer Baughman, director of operations at Ohio State’s Central Sterile Supply, was tasked with ensuring all the surgical tools were ready in time for the surgeries, which took place over two days in December — 10 on Friday, Dec. 13, 10 on the following Tuesday, Dec. 17.

Prepping the supplies took 40 hours alone, but the task didn’t feel so overwhelming to Baughman once she talked to her team about it.

“My staff was like, ‘Well of course. We’re at Ohio State — THE Ohio State. We set the stage for things like this,” she says. “They expect this type of stuff to happen.”

“It’s exciting to be a part of it and know that you’re helping so many people all at the same time,” Baughman says.

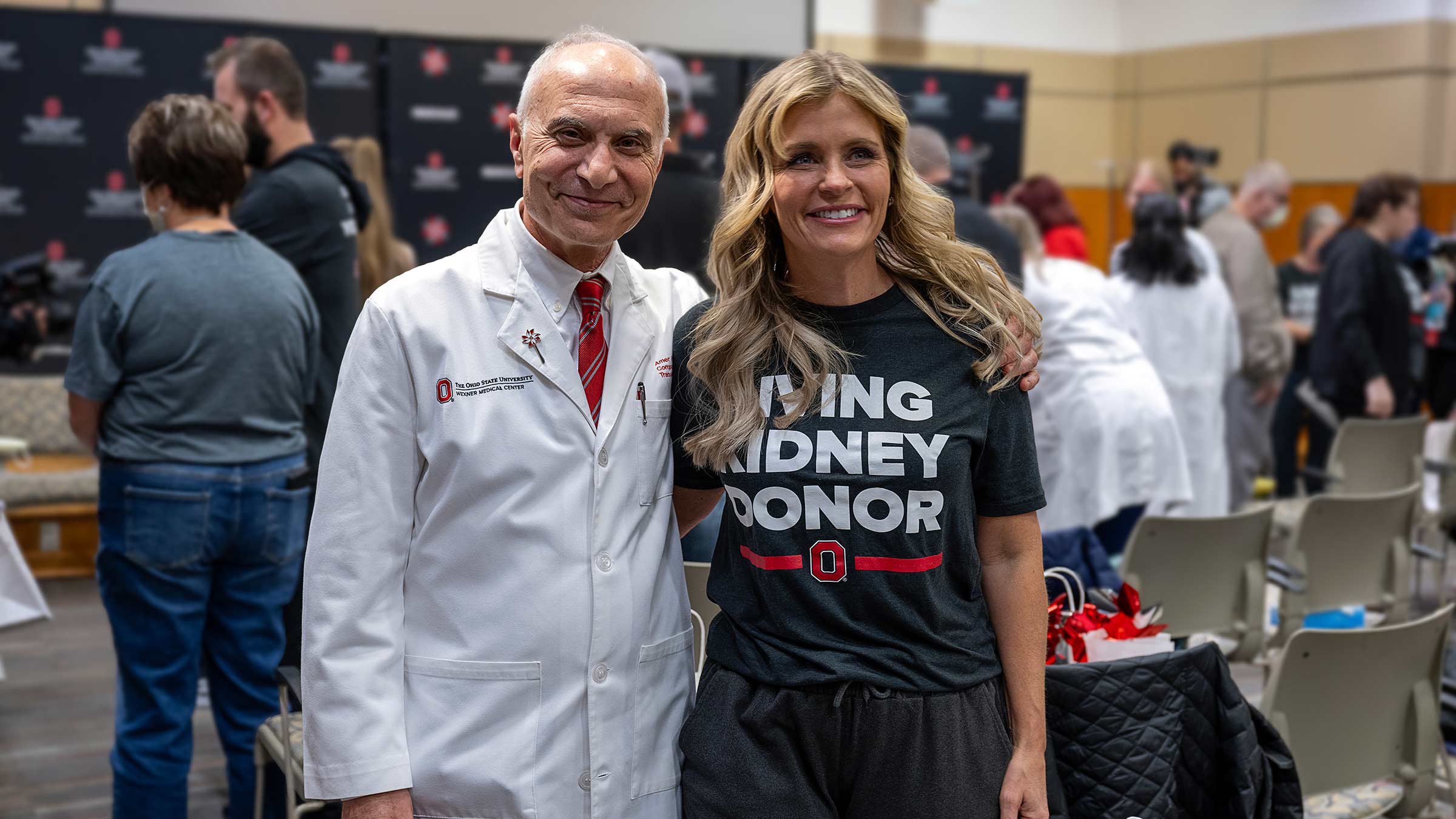

Once everything is in place, the chain begins, fittingly, with Amer Rajab, MD, PhD.

Dr. Rajab, Ohio State’s surgical director of kidney and pancreas transplantation, performed the first of the 20 surgeries, removing Fledderjohann’s kidney Friday morning. He would remove two more kidneys that day, then another three on Tuesday. It’s routine for him at this point — he’s removed more than 1,500 of them in his 25 years at Ohio State.

The surgeries themselves take around two hours, and each room has at least half a dozen people in it at any given time. A surgeon leads the work and teaches residents, fellows and medical students during the operation. A scrub tech and two anesthesiologists help with the process, and nurses assist in numerous ways — communicating with other operating rooms, delivering supplies when called upon.

If you’re picturing anything like the frenetic surgeries you may have seen on “ER,” don’t — the medical staff in the room are focused, certainly, but there’s a relaxed vibe. There’s always music playing: Post Malone in one room, Hall & Oates in another, Christmas music in a third.

Austin Schenk, MD, PhD, was among the other six surgeons who operated on patients in this chain. After one challenging kidney extraction on the first day, he remarked with admiration: “Everything takes longer for us to do than it does for Dr. Rajab. The rest of us are human.”

Dr. Rajab’s expertise is just one reason a chain this large can take place at Ohio State. More than 13,000 organ transplants have taken place here since 1967 — more than half of them kidneys.

“Ohio State has a bunch of really great people who work well together,” says Grace Gray, BSN, RN, coordinator of the kidney transplant waitlist at Ohio State. “That is the biggest thing, I would say. Our colleagues at our in-house tissue typing lab are incredible humans, let alone some of the most intelligent people I have ever worked with.”

What’s the effect of a kidney transplant chain?

According to the National Institutes of Health, about two Americans out of every 1,000 has end-stage kidney disease. A kidney transplant is their only path back to full health.

“I always tell my patients, ‘You don’t get your life back until you get your transplant,’” Dr. Rajab says.

There are more than 100,000 people awaiting transplants for all organs in the United States, and almost 90% of those people need kidneys.

Thanks to the work to make this chain go so smoothly, 10 people got their lives back, and an untold number of folks still waiting are that much closer to seeing the same dream play out for them.

“We prepare and check, but our recipients aren’t healthy, so you always worry that anything can happen,” Dr. Rajab says. “Literally, anything could have stopped the chain, but there were no hiccups whatsoever. We’re very happy, and the most important thing is that my patients are happy.”

Ready to learn more about living kidney donation?

We've got all the information you need to start the process.

Learn more

Support transplant innovation

Your gift sustains advances in lifesaving organ transplantation.

Donate now