Unlocking secrets to rewiring peripheral nervous system

Amy Moore, MD, FACS, is using innovative plastic surgery procedures to reanimate limbs, relieve debilitating pain and restore sensation for those with nerve injuries.

Amy Moore, MD, FACS, used to think of plastic surgery as what you see on “Nip/Tuck” or “Dr. 90210” — aesthetic or cosmetic procedures to enhance a person’s appearance.

But that was before she learned how to reanimate limbs, relieve debilitating pain and restore sensation, all through plastic surgery.

That was before she became one of the most renowned peripheral nerve surgeons in the world.

The possibilities of plastic surgery

Plastic surgery does include the cosmetic procedures many are familiar with, but the world of plastic surgery has evolved to encompass a wide array of procedures that reconstruct, rejuvenate and, in Moore’s case, rewire the body.

“It’s a diverse field that treats patients from young to old and from reconstructive to aesthetic,” Moore says.

“It is cosmetic surgery, but it is also reconstructive surgery after cancer resection, reconstruction for congenital differences, burn reconstruction, hand surgery and specialized microsurgery — the technically demanding surgical procedures that allow us to save limbs, reconstruct breasts and heal wounds,” Moore continues.

Moore, chair of The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center’s Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, is a plastic surgeon. But more specifically, she’s a peripheral nerve surgeon, operating on the peripheral nervous system, which comprises all of the nerves that extend out of the spinal cord into muscle and skin, allowing us to move, touch and feel.

Having joined Ohio State in 2019, both as the department chair and as the Robert L. Ruberg, MD, Alumni Chair in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, she‘s dedicated her practice to performing these intricate procedures to repair and restore function for patients.

Harnessing the body’s power to regrow itself

Unlike the brain and spinal cord, peripheral nerves can actually regrow after injury. It’s a powerful regrowth, Moore notes, but slow and inefficient — a millimeter a day, an inch a month, a foot and a half a year.

“If you have an injury in the nerves of the brachial plexus in the neck, it would take almost two years before the nerves can grow back down the arm and reach the muscles of the hand,” Moore says.

Meanwhile, muscle has an expiration date and can’t always wait that long for nerves to grow back to restore function. Within 12 to 18 months, muscle can permanently atrophy. At a certain point, its function can never be restored. That’s why it’s especially important, Moore says, to spread knowledge about this field as quickly as possible.

“This is a very young subspecialty, with very few dedicated peripheral nerve surgeons in the world. We’re still trying to get the good news out about the ways we can help, because when someone has this kind of injury, it’s a race against time to have it repaired before they lose the potential to save muscle.”

Patients are driving these advances

As a peripheral nerve surgeon, Moore is focused on getting a damaged nerve and its electrical signals back into that muscle before it’s too late.

And as a researcher, she’s able to drive solutions to the two biggest questions facing her field:

- How can we improve the speed and efficiency of nerve regrowth?

- Is it possible to rewire nerves to prevent muscle atrophy, avoid pain and restore motion?

“Research is the driver of innovation, and I appreciate that every day when I walk into my clinic,” Moore says. “Each of my patients and their problems are so different, so I’m able to really engage and think about each of them beyond just a procedure.”

It’s her patients’ unique injuries that continue to motivate her research and creativity at Ohio State, building upon a career sparked in childhood.

Becoming ‘Dr.’ Moore

Moore’s dream of becoming a physician started young, while volunteering at a Veterans Affairs hospital with her father, who served in the United States Army and later continued his career in the VA medical system as an administrator. Her interest turned specifically to surgery while she was in high school, when an inspiring orthopedic surgeon got her back onto the soccer field after an injury. In medical school, when paired to work with a plastic surgeon, she found her niche.

She specialized in hand surgery, knowing that it would allow her to continue to delve into nerve regeneration as both a surgeon and scientist, blending her loves for anatomy, nerve reanimation and bringing function back to patients’ bodies.

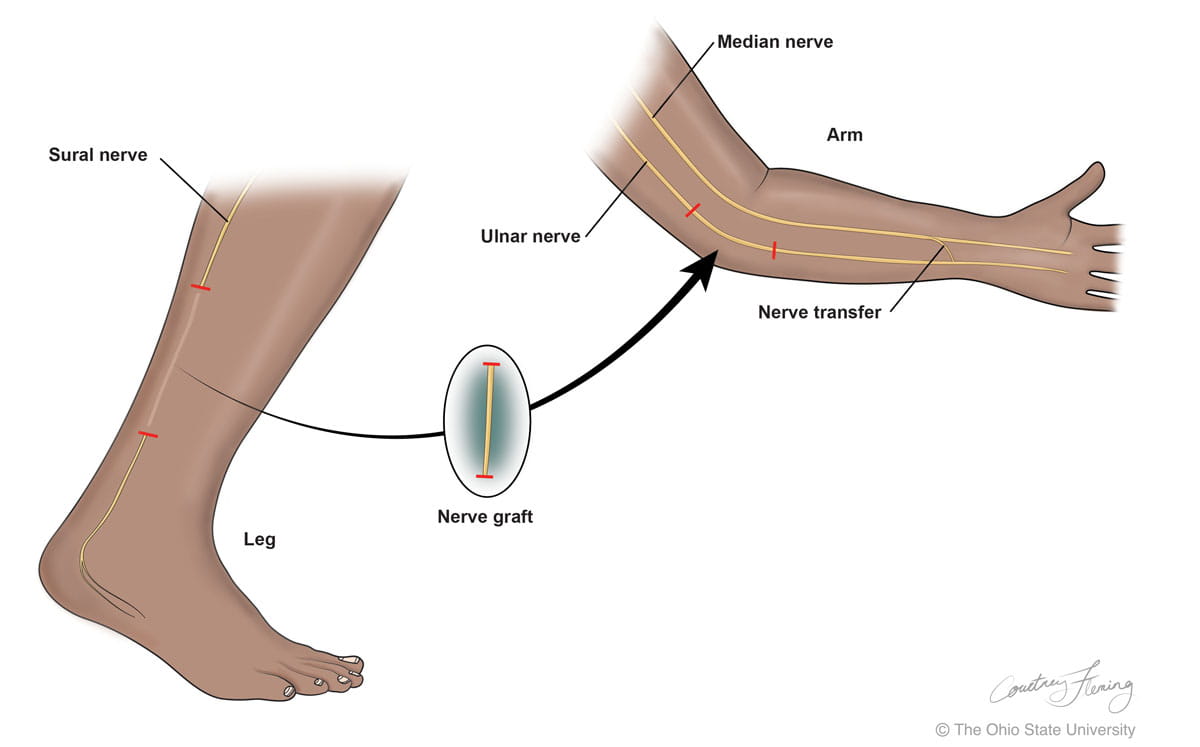

During her residency, Moore studied under the distinguished nerve expert Susan Mackinnon, MD, spending two years discovering how to improve our bodies’ peripheral nervous systems with nerve regeneration. Mackinnon had developed revolutionary “nerve transfers” that capitalize on the body’s “redundancies” — nerves that can do the same movement in one part of the body as another.

Nerve transfer surgery takes a nerve that’s working in one muscle but isn’t much needed, and moves it to replace a nerve that isn’t working but performs a needed function in the body. “For example,” Moore says, “we have two muscles that bend the wrist. We can rewire one of the nerves from the wrist to instead power the bending of the elbow, and the brain can handle this change because of its plasticity (its ability to adapt).”

What Mackinnon began, Moore is carrying on, reanimating nerves everywhere in the body.

The magic of nerve transfers

One of Moore’s patients, a professional guitarist, was in a serious car wreck that severely damaged a major nerve in his left arm, leaving a gap between two ends. Moore borrowed a nerve from his leg and transferred it to his arm like an extension cord. She also performed a nerve transfer that saved the delicate muscles of his hand, allowing him to stretch his fingers across his guitar’s frets again and maintain his livelihood.

She’s helped a 15-year-old return to his school’s varsity basketball team a year after a motorcycle accident injured his spine, preventing him from using the muscles that power the lower leg. By taking redundant nerves of his thigh and rewiring them to a different spot in the leg, Moore restored function to the gastrocnemius muscle, which helps us point our toes and push off the ground when running.

She’s helped a 15-year-old return to his school’s varsity basketball team a year after a motorcycle accident injured his spine, preventing him from using the muscles that power the lower leg. By taking redundant nerves of his thigh and rewiring them to a different spot in the leg, Moore restored function to the gastrocnemius muscle, which helps us point our toes and push off the ground when running.

After such successes, she was called in to examine children who developed acute flaccid myelitis (AFM), a neurological condition that many have likened to polio for the way it paralyzes limbs.

She noticed that many of these young patients with AFM were able to wiggle their toes even though they couldn’t stand. After rewiring the nerves that move the toes to a place where they could help stabilize the hip and thigh, Moore helped enable many of these children to walk again.

The ‘surgeon’s surgeon’

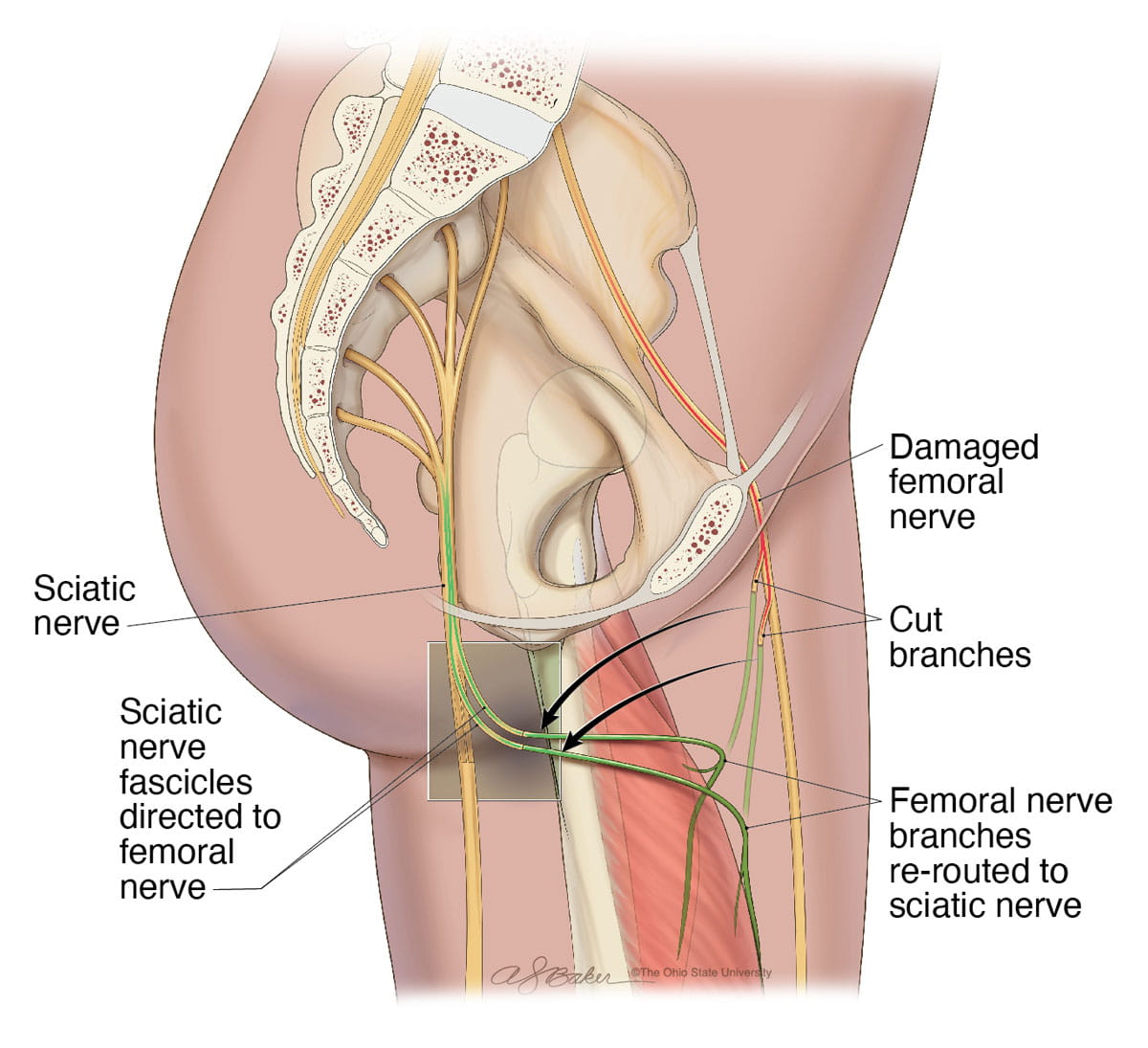

Recently, an Ohio State Wexner Medical Center patient named Philip regained function of his leg through a unique collaboration between the plastic and reconstructive surgery team and the surgical oncologists at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – James Cancer Hospital and Solove Research Institute (OSUCCC – James).

“A tumor had clearly infiltrated one of Philip’s important nerves that allows function of the leg — the femoral nerve. He was really struggling to walk,” says OSUCCC – James surgical oncologist Valerie Grignol, MD.

“A tumor had clearly infiltrated one of Philip’s important nerves that allows function of the leg — the femoral nerve. He was really struggling to walk,” says OSUCCC – James surgical oncologist Valerie Grignol, MD.

Grignol’s team performed a resection of the tumor and had to cut into a portion of Philip’s femoral nerve. It could have meant that Philip would never use his leg normally again.

But Moore was in the operating room, too. Moore reconstructed the femoral nerve after the tumor was removed.

Today, Philip has regained near-complete function of the leg, and his tumor is gone. This is why Moore describes plastic surgeons as true collaborators — the “surgeon’s surgeons.”

Plastic and reconstructive surgery procedures often happen in tandem with or following a different type of surgery, with a plastic surgeon reconstructing defects caused by previous surgeries or addressing wounds that developed from those procedures.

Creating new options for Ohio State patients

It’s not common that those “surgeon’s surgeons” are able to integrate so fully with other teams, but Moore has helped make Ohio State a destination for unique partnerships.

“The collaboration with the plastic and reconstructive team here — specifically Dr. Moore — has led to significant benefit for patient care in terms of offering procedures that weren’t previously available,” Grignol says. “We can offer patients reconstructive options that impact their quality of life — things that they may not have known were feasible. Sometimes, physicians they’ve met elsewhere have led them to believe that maybe their tumor wasn’t treatable [because of how resection would affect the nerves].”

Moore says it’s that benefit to patients’ quality of life that drives everything she does.

“Nerve surgery is very rewarding,” she says. “A patient might come to me in pain, with a lack of motion, or they can’t feel — and I can perform surgery that alleviates pain and can restore function.”

“I always tell patients that we are going to be good friends, because it takes such a long time for nerves to grow. I follow my patients for years, and it’s that connection with them that drives my next idea, my next surgical procedure. They continue to foster my interest in research so that I can provide the care that each patient deserves.”

Building more revolutionary solutions, starting with veterans

While continuing to provide world-class care for patients in need of nerve expertise, Moore is currently embarking on a new research endeavor funded by the U.S. Department of Defense.

It’s a funding source she’s grown very comfortable with, thanks to her experiences with veterans. In addition to her father’s Army background, Moore’s grandfather was instrumental in developing radar detection in the Army. Her husband was also enlisted in the Army, which allowed him to travel the world and paid for his college education.

“I have a lot of positive influences from the military,” Moore says. “And I feel deeply connected with what it takes to serve and what a privilege it is to be an American citizen.”

“It’s always been in the back of my mind: How can I contribute and serve, not being physically in the military?”

This passion led her to develop an Ohio State military medicine program, buoyed by the recent recruitment of U.S. Navy veteran Jason Souza, MD, as director of the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center’s Advanced Limb Reconstruction Program.

“I am excited to partner with the Department of Defense to help treat our nation’s war-fighters who have also suffered devastating nerve injuries,” Moore says.

Creating the future of nerve surgery

Moore is currently leading two nerve injury trials, both funded by the Department of Defense.

One trial explores how electrical stimulation from a handheld device can increase the speed and efficiency of nerve growth.

The second trial assesses arm use after nerve injury, and how rehabilitation can improve the use of a hand that’s been injured. What researchers discover from this trial could tell them more about just how much more patients with nerve injuries can improve, long after their injury.

“Nerve surgery is exciting because we’ve just tapped into it — it’s such a new field,” Moore says. “I feel so much gratitude for what I do. It is a privilege to develop a whole department while also continuing to do what I love with my clinical work and research. It is an exciting time because there is so much more for us to discover and build at Ohio State.”