Cardiologist changing the way we care for women’s cardiovascular health

What Laxmi Mehta, MD, wants women — and their doctors — to know about their hearts

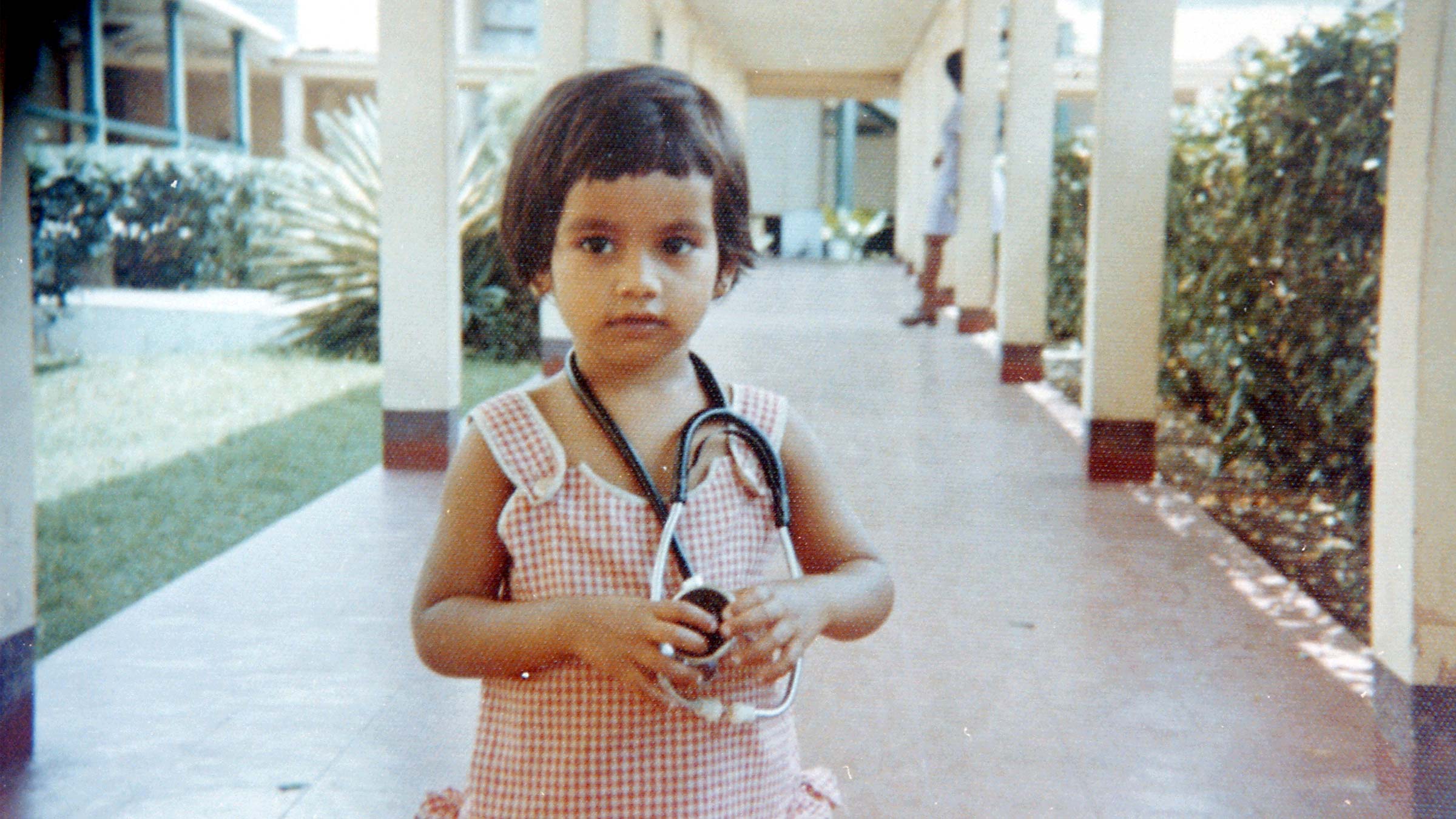

Dr. Laxmi Mehta’s professional passion was born in the cardiac unit of a Columbus hospital during what was supposed to be a routine career-shadowing day for the 14-year-old high school freshman. Her father was a physician and arranged for her to shadow a cardiologist colleague. Her initial impression wasn’t favorable.

“They showed me cardiac catheterization cases and the heart monitor in an empty ICU room. When they were talking to me about their training — at that time it was two years of internal medicine and two years of cardiology fellowship,” Dr. Mehta recalls, “I was thinking, ‘Gosh, who would be crazy enough to go through that many years of education? That’s too long and that’s not for me.’”

Also starkly standing out: the absence of any women in white coats in the cardiac unit.

That youthful dismissal evaporated a few hours later, when the heartburn her father had experienced since the night before got so bad that he walked himself to the cardiology office and had a cardiac catheterization in that same cath lab. While Dr. Mehta was having lunch with the colleague, her father was having a heart attack.

“I was there when they took him to the ICU and the cardiac bed was the same bed I saw earlier,” Dr. Mehta says. “It was surreal. The empty bed suddenly became his bed.”

When her mother arrived at the hospital, the teenager had to draw on what she had just learned to explain what was happening. Her father thankfully survived.

“After that I decided I was going into cardiology,” Dr. Mehta says. “I realized that people just didn’t know enough about heart disease.”

Three decades later, Laxmi Mehta, MD, has done more than just educate people about heart disease. She’s become an advocate for a better understanding of women’s heart health, and for the advancement of women as practitioners.

Dr. Mehta serves as director of Preventive Cardiology and Women’s Cardiovascular Health at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, where she holds the Sarah Ross Soter Endowed Chair in Women’s Cardiovascular Health at The Ohio State University College of Medicine. And she recently took on an additional role as chief well-being liaison and faculty director of the Gabbe Health and Well-Being program, which is aimed at improving clinician wellness.

Heart disease in women: Unrecognized symptoms, misunderstood signs

Through medical history, understanding the health and well-being of women has taken a backseat. Women were often excluded from clinical trials, and the idea that women might experience disease differently than men — or that it matters — has generally gone unexamined. That’s as true for cardiology as for any other area of medicine.

But Dr. Mehta believes the days of gender inequity in cardiovascular health may now be numbered.

While many people think of heart disease as a problem mainly for men, it’s the No. 1 killer of women, just as it is for men and for people of most racial and ethnic groups in the United States. One in five deaths in the country is from heart disease.

Dr. Mehta also knows that heart disease is different for women than men in ways that haven’t been adequately studied, and that this means heart disease in women goes dangerously unrecognized.

Too often, Dr. Mehta says, this leads uninformed practitioners to ignore or dismiss women’s heart-related symptoms. Women are left doubting their own instincts and experiences.

For example, women don’t always develop blockages in major arteries, as men tend to; their blockages may be spread across smaller vessels. In addition to chest pain, women are more likely to feel discomfort in the neck, jaw, shoulder, upper back or upper abdomen.

“Even medical practitioners aren’t always aware of how a heart attack can be different for a woman,” she says.A heart catheterization — the classic diagnostic method for heart attack — may find no blockage in a woman’s artery even as she’s having a heart attack.

‘You’re gonna need to see Dr. Mehta’

Pamela Bork was typical of many women. The tightness in her chest didn’t feel right, so she went to the emergency department and was given some diagnostic tests. She almost didn’t stick around for the results.

“I honestly almost left the ED,” says Bork, a physical therapist who works for The Ohio State University’s Student Health Services. “I was halfway out of my chair and putting on my coat when my phone started to ping.” She learned, to her shock, that she was having a heart attack.

“I was stunned at how light it was,” she says of the pressure she felt. “It felt like someone gently pushing on my chest, like you feel when you drank a soda and you need to burp.”

As soon as she began ongoing treatment at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center Richard M. Ross Heart Hospital, Bork says, “I kept hearing about Dr. Mehta. ‘You’re gonna need to see Dr. Mehta.’

“Now I can see why,” she says. “I felt very at ease talking with her. You know she knows what she’s talking about, but she brings things down to your level and explains them to you.”

That doesn’t include sugarcoating the facts. Bork, an avid runner who was training for a half-marathon before her heart attack, wanted to know how soon she could resume running.

“I said, ‘I’m not doing anything. I’m gaining weight,’” Bork says she told Dr. Mehta. “She told me straight out, ‘You’re gonna have to get over that.’”

Bork appreciated the directness, but is equally quick to point out Dr. Mehta’s empathy and the fact that, when Bork calls the heart hospital with a question about her care, it usually is Dr. Mehta herself who returns the call before the end of the day.

Being a pathfinder to more women in cardiology

Dr. Mehta understands the power of ensuring more women pursue and stay in cardiology careers. A casual visitor need only look at the annual cardiology fellowship class photos on display in the Dorothy M. Davis Heart and Lung Research Institute to see the changing role of women in cardiology: The groups of the 1990s, nearly all white and male, have given way to racially and ethnically diverse classes with many women.

Today’s cardiology fellowship class at the College of Medicine is close to 40% female (the national average is 24%). The ranks of faculty also have more women, and at least some credit goes to Dr. Mehta.

“She recruited four women in the past year,” says Ayesha Hasan, MD, interim division director of Cardiovascular Medicine and clinical professor of Internal Medicine in the College of Medicine, “and has mentored many faculty.”

Alli Bigeh, DO, a current cardiology fellow at Ohio State, counts herself among those.

“She’s actually a big reason why I came to Ohio State,” Dr. Bigeh says. “Women’s cardiology is still evolving; it’s still relatively small and close-knit. When I was going through residency, I realized that having a female mentor — someone to look up to — is very important to me.”

Lauren Lastinger, MD, who is further along in her career, began working with Dr. Mehta as a young physician when she joined the cardiology team.

“As a younger trainee coming up you hear, ‘Oh, Dr. Mehta has written this and published that and accomplished this.’ Before I even knew her as a mentor and a friend, I sort of had her on a professional pedestal.

“When I joined the team, she put me in front of several opportunities that have set me on this path to being professionally promoted,” Dr. Lastinger says. “I kind of joke that she puts me on moving trains. That’s what I think a good mentor does: She doesn’t do the work for you, but when you don’t have any connections, she helps you make those.”

A leader for women’s cardiovascular health

Dr. Mehta was recruited to the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center in 2007 to establish and direct the Women’s Cardiovascular Health Clinic. She threw herself into grassroots community education. “We did a lot of outreach in the community,” she says. “I gave numerous talks on women’s heart health and prevention.”

Joining efforts such as the American Heart Association (AHA) “Go Red for Women” campaign led naturally to greater involvement with that association and with the American College of Cardiology (ACC), a professional society in which Dr. Mehta continued to break barriers as its first female president/governor. For a physician who was female and young, being tapped to serve on prestigious AHA and ACC committees took a lot of persistence — a quality she reportedly has in spades. She’s described by a cardiology colleague as the type of person who “builds her own dance floor.”

Today, Dr. Mehta is a nationally known educator and speaker on women’s cardiovascular health and disease prevention. She’s a national research leader, having served as lead author on several AHA scientific statements. In 2016, she chaired the association’s first-ever statement on acute myocardial infarction (heart attack) in women. It held that a greater focus on women and cardiovascular disease risk and greater use of evidence-based treatments were partly responsible for a dramatic decline in mortality rates for women.

That same year, she received the inaugural Excellence in Advocacy Award from the ACC.

In 2021, an AHA policy statement she chaired served as a call to action around the fact that the United States has the highest rates of maternal mortality in the developed world, with cardiovascular disease as the leading cause. The statement emphasized inequitable outcomes for childbearing women in the United States and recommended making maternal health a priority in programming, education, research and policy development.

“The tragic irony is that moms are typically in charge of the health for everyone in their families, yet they are dying due to lack of the right kind of care at the moment they need it most,” Dr. Mehta says.

The cardiologists’ work-life imbalance: “You didn’t always eat. You didn’t always drink water.”

Despite her early determination to be a cardiologist, Dr. Mehta passed up the first chance to apply for a cardiology fellowship. At the time, she didn’t see a place for herself in the field.

It troubled her that she didn’t see many women. And most importantly, she says, she knew she wanted to have children and didn’t believe it would be possible as a cardiologist.

However, a chief of cardiology who recognized her potential encouraged her to apply and promised to be supportive.

He kept his promise, Dr. Mehta says, but that didn’t mean she had an easy time as a cardiology fellow at William Beaumont Hospital in Michigan.

“There were no work-hour rules then,” she recalls. “Sometimes we would work 36 to 40 hours straight. You didn’t always eat. You didn’t always drink water.”

While pregnant with her first child, she saw patients one weekend while dragging an IV drip and pole with her because a nurse had noticed she was dehydrated. Dr. Mehta knew the demands of a physician in training were tough. And she knew that, as a woman in a discipline with very few others, she had more to prove.

“If you called off, you weren’t good enough to be in the field,” she says.

With a husband in a job requiring frequent travel, she faced child care crunches that are familiar to most working parents, if a bit more extreme.

“The daycare closed at 6:30,” she says. “I would sneak out, run over in between patients around 6 p.m., bring my son to clinic and give him to the nurse. I’d say, ‘Could you hold him? I’m just running into the next room.’”

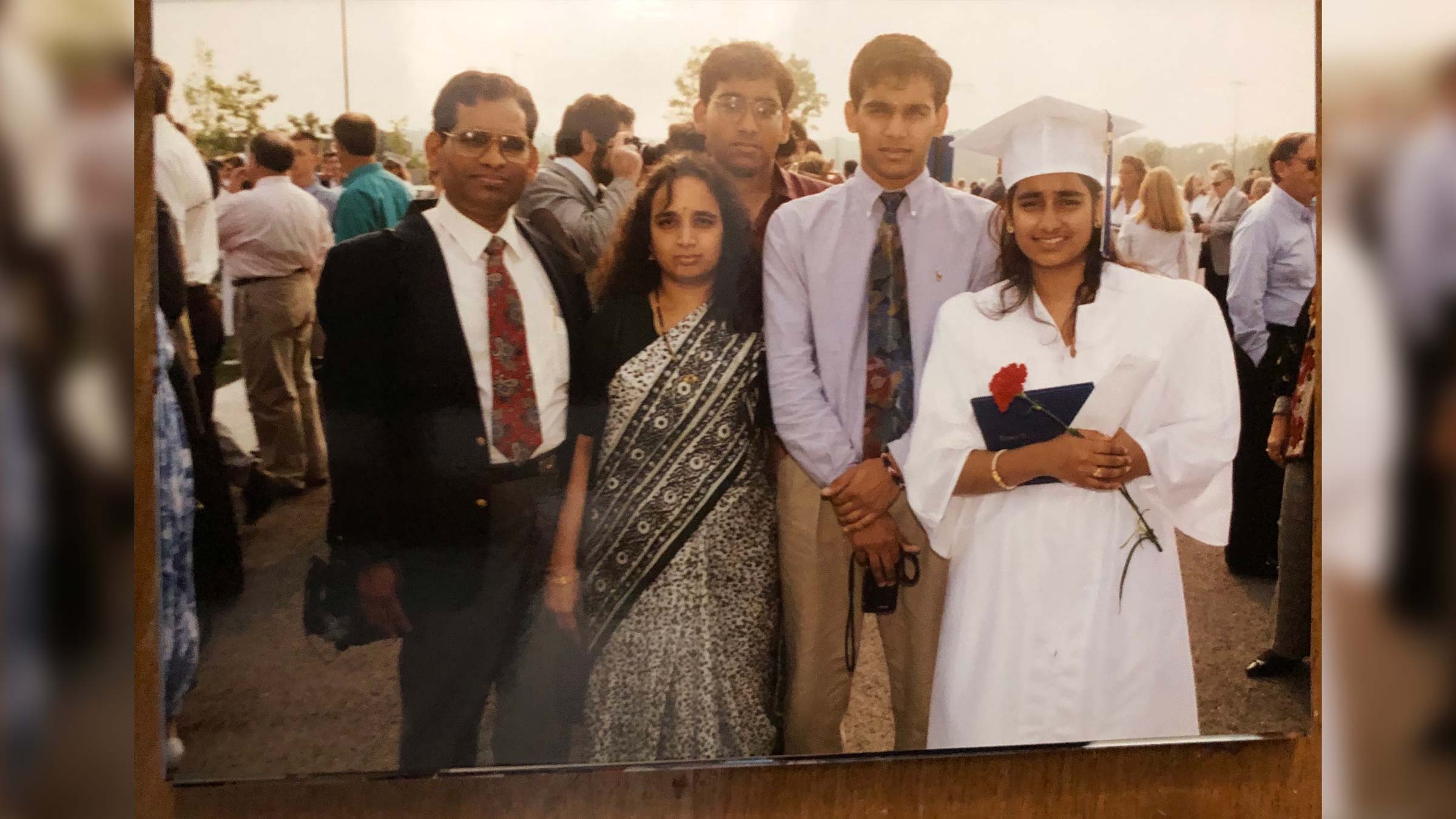

It didn’t occur to the driven young physician and daughter of a high-achieving immigrant family — her two brothers also are physicians — to object to a grueling workload.

“I trained in a time where physician culture was such that well-being was not a thing,” Dr. Mehta says. “You sacrificed your body and your life for medicine, and I understood that was part of the job.”

Early in her career, when she was part of a committee conducting a survey on working conditions for women in cardiology and was invited to write a paper on the topic of burnout, she was puzzled. “I was thinking, ‘well, we’re cardiologists; we don’t burn out,’” she says. “And then I started working on the data and I saw there were a lot of people burning out.”

Leading a shift to a healthy work culture

In her new role as Gabbe Health and Well-Being program director, she’s at the forefront of battling burnout, a phenomenon she once didn’t recognize as a condition in cardiology.

“The only way we can take the best care of our patients is when we take the best care of ourselves and our team,” she says.

For today’s physicians, the demands have shifted; now they include bureaucracy, paperwork and the requirements of electronic health records.

“Medicine has changed,” Dr. Mehta says. “People are burning out because they’re spending time in front of a computer rather than with a patient. People don’t mind taking care of the patient; they mind taking care of the computer.”

Inspiring change for the next generation

She recognizes the difficulty in trying to change the culture of medicine on two fronts, but she’s intent on both boosting clinician/researcher well-being and continuing efforts to raise awareness of competency in cardiology for women.

“What I really like seeing is the younger generation understand that women’s cardiac health differences exist,” Dr. Mehta says. “Because when you can change their knowledge, then they can make the change. They can be inspired to do the research. They can be inspired to take care of patients a better way.

“When I have students tell me, ‘I heard women’s hearts are different,’ then I know they’ve been listening.”

Your heart is in the right place

Learn more about advances in care and treatment for patients at The Ohio State University Heart and Vascular Center.

Expert care starts here