When kidneys become available for transplant, the clock begins on a time-sensitive analysis to determine if the organ is suitable for the recipient.

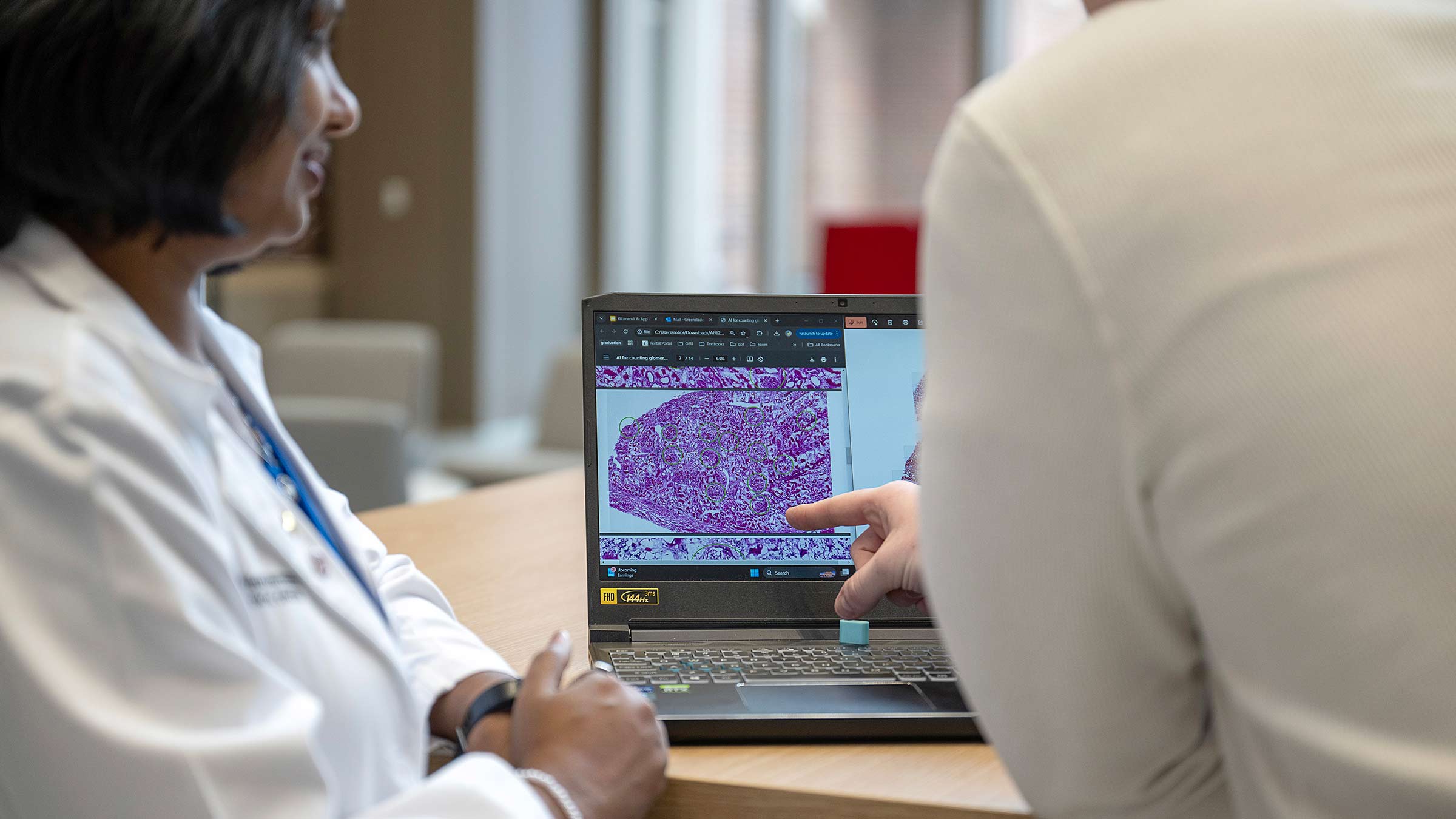

The process involves counting glomeruli, small blood vessels which act as filters for the kidney. The tedious and time-consuming process is subject to human error — which can mean counting and re-counting — all while the clock ticks and a transplant recipient waits for news that could save their life.

It’s a task The Ohio State University College of Medicine faculty and computer science students recently set out to reimagine with the help of artificial intelligence.

Swati Satturwar, MD, knew AI could be harnessed to expedite the glomeruli-counting process.

“There is a short, crucial window before a kidney transplant can occur to determine if the donor organ is suitable for the recipient,” says Dr. Satturwar, assistant professor of Pathology. “An AI app could help pathologists streamline their process, saving time and ensuring lifesaving transplants can happen as soon as possible.”

Solving health care problems through competition

The idea and early stages of an application came about through the Ohio State College of Medicine Appathon, a competition to bring together clinicians, faculty, researchers and engineering students to develop software to solve current health care problems. The event focused on AI and ideas for an AI-based app that could improve research, clinical practice or patient care.

With Dr. Satturwar’s idea, computer science and engineering students Robert Greenslade and Yuting Che worked to develop software that could quickly analyze kidney images and count the number of glomeruli. The results would then be shared back with medical professionals for verification.

Seeing promise in AI-based apps

Ultimately, the students’ app prototype analyzed kidney images and identified and predicted where there is tissue, but the pair found they needed more computing power than their personal computers had to build an AI model that could successfully count glomeruli.

Still, Appathon judges saw the immense promise of the app and awarded the group first place. Greenslade and Che are now working with Dr. Satturwar to partner with the Ohio Supercomputer Center to continue training their AI model with more powerful computing resources.

These are the kinds of solutions Derek Harmon, PhD, associate professor of Biomedical Education and Anatomy, envisioned when he began the College of Medicine Appathon.

“There are clinicians and researchers in the College of Medicine who have an idea but may lack the technical expertise or funds to develop an app,” Dr. Harmon says. “Then there are computer science students who have the technical skill sets, but they don’t know that these problems exist. This brings everyone together, working toward solutions.”

Working together to advance medicine and science

Learning about the stumbling blocks in other people’s work is critical for new app development, Greenslade says.

“Sometimes people just accept that something is going to take a long time to do, and they don’t realize that there can be a better, easier way,” he says.

The app competition also allows students to gain real-world experience while providing the primary investigators with a prototype to pursue additional funding.

“It has never been more important to work together across disciplines to develop innovative solutions to today’s health care challenges,” says Carol R. Bradford, MD, MS, FACS, dean of the Ohio State College of Medicine. “The projects developed during the Appathon are inspiring examples of what we can do when we work collaboratively.”

Second place: an app with promise for cancer drug research

When junior computer science and engineering and neuroscience major Sagar Shah saw an app proposal involving protein interactions and drug development — an area he knew little about — the challenge appealed to him. The idea was proposed by Francesca Cottini, MD, assistant professor of Internal Medicine, and Emanuele Cocucci, MD, PhD, associate professor of Pharmaceutics and Pharmacology, whose research involves developing therapies for patients with multiple myeloma.

“This proposal stuck out because I didn’t know much about the topic, and I wanted to try something new. That’s why opportunities to work with others across disciplines are so important,” Shah says.

Appathon judges awarded second place to Shah’s app, a prototype that leverages existing repositories of data to predict which peptides have the best chances of binding with a particular protein. The results could help scientists like Drs. Cottini and Cocucci prioritize which targeted peptides to test in their cancer research.

“This AI tool will be instrumental in helping us identify new peptides to study and speed the development of novel drugs for cancer patients,” Dr. Cottini says.

“There are so many new possibilities with AI,” Dr. Harmon says. “From kidney visualization and analysis to solving complex protein-folding for drug development, that’s the spectrum of AI in a nutshell.”