Ohio State researcher determined to find out what exercise really does in the body

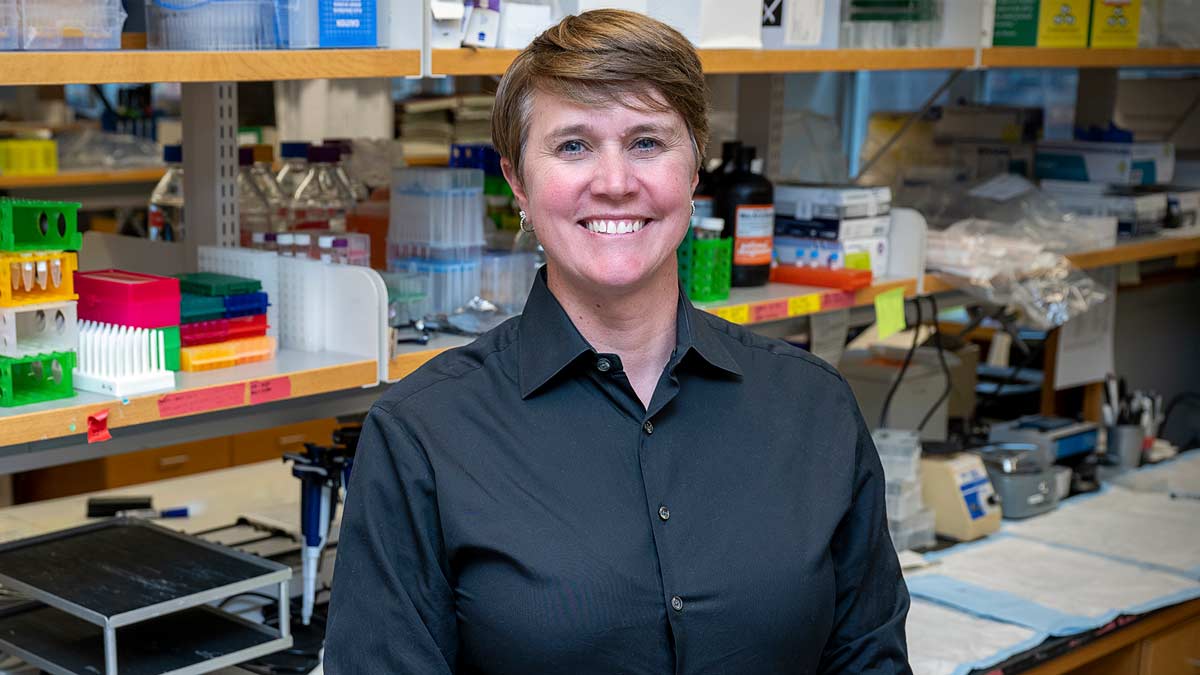

Need more motivation to get moving? Kristin Stanford, PhD, might have the answers.

When Kristin Stanford, PhD, was a Big Ten water polo player, she had no idea her daily workouts set her up for a lifetime of healthier outcomes.

But training among top athletes did make her curious about why some teammates performed differently and how exercise is beneficial on a cellular level.

These questions launched her career dedicated to understanding why exercise leaves a biological imprint on your cells — and your offspring. Finding answers could go far beyond motivating people to get fit. It could lead to generations of healthier people, as well as novel treatments for cardiovascular disease.

Benefits of exercise go far beyond weight loss

It’s common knowledge that exercise is good for your body. Many consider exercise only as a way to lose weight. However, little is known about why exercise benefits the body on a cellular and molecular level. Dr. Stanford, a physiology and cell biology researcher at The Ohio State University College of Medicine and associate director of the Dorothy M. Davis Heart and Lung Research Institute, hopes her research will uncover additional unexpected benefits.

For example, what if you had an exact formula for how much moderate exercise is needed to benefit the heart? And what if you knew that your fitness as a pregnant or nursing parent sets up your child for a lifetime of better health?

That might be just the motivation to lace up your gym shoes in the morning.

“We’re making sure people understand those benefits — independent of weight loss — by showing why it’s important to metabolism, the heart and the overall body.”

“There are so many different ways exercise promotes health,” Dr. Stanford says.

Some people can’t get moving due to age or illness. By understanding the mechanisms behind fitness, Dr. Stanford hopes to discover novel potential therapies that would benefit those who can’t exercise.

“We know that exercise is correlated with positive outcomes across the lifespan, across sexes and in different disease states. We don’t always know why,” Dr. Stanford says.

Research results get closer to revealing why exercise is healthy

To find out how exercise is a tool to promote overall health, Dr. Stanford turns to her lab, where she studies molecular changes in tissues with and without exercise. Her goal is to determine exactly how exercise is a tool to promote overall health.

Dr. Stanford has been on a decade-long journey of studying how brown adipose tissue — called brown fat and considered a healthy fat — affects the body. Brown fat burns energy and generates heat. It expands with cold exposure, making it the same fat that keeps hibernating bears warm. Scientists have studied brown fat for years after discovering it exists in small amounts in adults. Researchers previously thought it was only infants who benefit from its warming nature.

Early in her research career, Dr. Stanford found that a molecule produced by brown fat, a lipokine, surges in the bloodstream after exercise. Lipokines help regulate lipids (such as cholesterol) and metabolism.

Dr. Stanford performed an initial analysis of brown fat after exercise. With the help of a colleague studying how brown fat helps keep the body warm, Dr. Stanford discovered the same lipokine that was found to be elevated with cold was also elevated with exercise. “We knew then we were on to something, and that it was probably doing something important,” she says.

Her research over the last eight years has shown that brown fat improves cardiovascular function in mice. She also found that patients with heart disease have lower levels of this lipokine. That finding is key to developing a way to increase this lipokine with a novel potential therapy for treating cardiovascular disease.

Exercising before and during pregnancy benefits the next generation

Dr. Stanford is also interested in studying how parents’ exercise affects their offspring. Her research has shown that even moderate exercise interventions before and during pregnancy benefit animal offspring throughout their lifespan. “Animal moms who exercise two weeks before conception and then during gestation have offspring with improved metabolism throughout their lifespan,” she says.

In male animals, a male’s exercise regimen before conception also improves the offspring’s metabolic health. Dr. Stanford and her team fed male mice a standard or high-fat diet for three weeks. Some mice from each diet group were either sedentary or exercised freely. “When the male exercised, even on a high-fat diet, we saw improved metabolic health in their adult offspring,” Dr. Stanford says.

In human breast milk, Dr. Stanford’s team found milk composition changes with exercise. Maternal exercise increases a specific oligosaccharide — complex sugars that promote beneficial gut bacteria growth, support the development of the immune system and may benefit cognitive development.

“The more active you are, the more of this compound you’ll have in the breast milk. We are seeing this effect in animals and humans,” Dr. Stanford says.

Dr. Stanford is deliberate in focusing her research on both men and women, noting that past research and clinical trials included mainly on males. “I think the shift in focus is important, because we know that the answers and the outcomes are different among males and females.”

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) policy to consider sex as a biological variable only went into effect in 2016, shortly after Dr. Stanford began her career at Ohio State.

Exercise research leads to as many questions as answers

Research, in general, is a long road. Some studies monumentally determine the direction of a project or even a career — like when Dr. Stanford discovered that brown adipose tissue releases the same lipokine after exercise as it does when exposed to cold. There are even moments of wild amazement, like when Dr. Stanford extracted strawberry DNA for her 6-year-old son’s class.

Today, Dr. Stanford is working diligently to find answers to many questions about why exercise matters, such as:

- What are the mechanisms of exercise that improve health?

- How is exercise different in ages and disease states?

- How is exercise different in men versus women?

- How does exercise benefit offspring?

Ohio State’s collaborative culture keeps Dr. Stanford motivated

Dr. Stanford hopes her work will lead to translational research that can benefit humans. Demystifying the role of exercise in total health can help more people stay motivated. And understanding the mechanisms for how exercise helps metabolism, cardiovascular health and even mental health could lead to finding pharmaceutical therapies for those who need it.

To get there, Dr. Stanford says relying on her lab team’s support at the Davis Heart and Lung Research Institute and collaborating with colleagues in other departments across the medical center has been the best part of working at Ohio State.

“Everything’s about the people that you work with,” Dr. Stanford says.

“We’ve got a wonderful team in the lab and great collaborators around campus, and I think that’s really helped us grow the research,” Dr. Stanford says.

As for her exercise regime, Dr. Stanford has traded in her daily water polo workouts for running shoes. She’s training to run a marathon in all 50 states.

When you give to The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, you’re helping improve lives

We’re committed to making advancements in research, education and patient care that will have an impact throughout Ohio and the world.

Ways to Give