Have you experienced loss of smell? Ohio State is leading research on devices to improve and treat anosmia

Anosmia, or loss of smell, can be caused by many conditions — from head injuries and viral infections (such as COVID-19) to aging and neurological conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease and multiple sclerosis. Some medications and treatments can even trigger anosmia.

It can be a frustrating symptom, because it not only means you can’t smell properly, but that you can’t enjoy the taste of food the same way. And you can’t easily tell when food is spoiled, or if there’s dangerous smoke or gas nearby.

As Kai Zhao, PhD, points out, there’s currently no effective treatment.

“For centuries, there have been innovations to help people see and hear better, but there haven’t been worthwhile methods that improve olfactory function or the ability to smell,” says Dr. Zhao, a professor of nasal physiology in The Ohio State University College of Medicine’s Department of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery.

What Ohio State scientists have developed to improve smell

Led by Dr. Zhao, researchers at the Ohio State College of Medicine designed non-invasive prototypes that improve people’s ability to smell. That includes both healthy people and people who are experiencing anosmia or hyposmia (partial loss of smell).

The team is the first in the world to create these tools.

“The smell aids our team developed hold the promise of becoming effective, over-the-counter therapies like eyeglasses and hearing aids,” Dr. Zhao says.

How the smell aids work

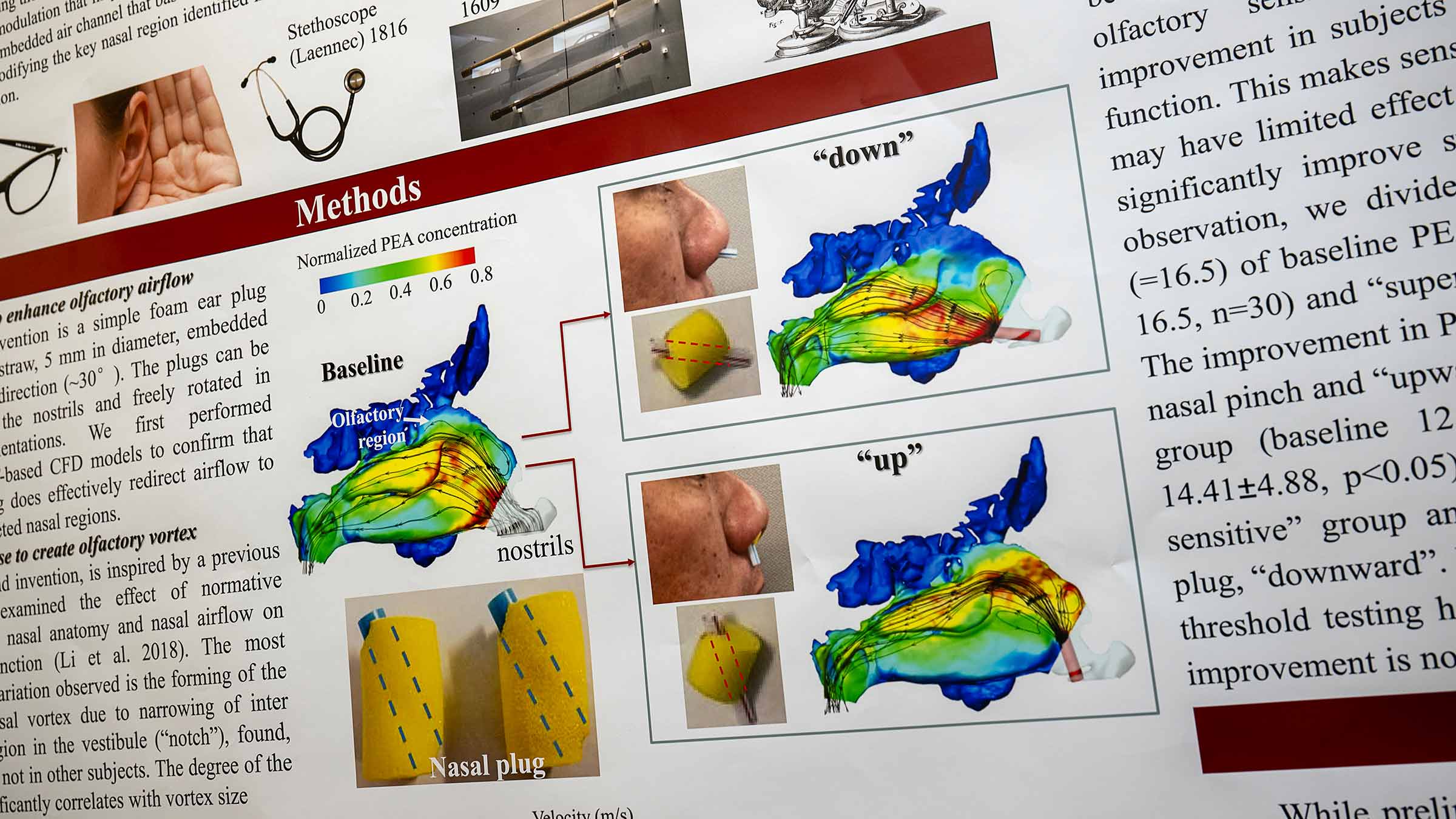

The Ohio State scientists led a clinical trial, recently published in BMC Medicine, that tested two prototypes that increase air flow to the area of the nasal cavity responsible for sense of smell.

Using foam ear plugs, they created nasal plugs that redirect air flow to that region of the nose, carrying odors along with it. A nasal clip helps pinch a valve in the nose that can also intensify the air flow to that area.

Who tested the smell aid prototypes

They tested 58 people with no smell loss or conditions that could affect smell, and 54 people who do have some form of smell loss.

Many in the group with smell loss — 69% — lost some sense of smell as a result of COVID-19 infection. The rest of the group experiences anosmia or hyposmia because of nasal polyps, head injuries or head and neck cancer or surgery.

How smell aid prototypes were tested

For people without any noteworthy smell loss, they tested the nose plugs by squeezing and sniffing two bottles one after another, identifying which bottle contained the actual odor.

People who did already have a smell deficit used an odor identification test from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This involves nine scratch-and-sniff cards with odors on them, and the participants scratched and smelled the cards in random odor, identifying odors based on four multiple choices.

Both testing groups tried the test with and without the nasal plugs.

Clinical trial results

Participants with typical smell function were able to detect odors much more when using the prototypes.

“The improvement is quite robust with an effect size of 2.1 (95%CI: 0.334 -3.797),” Dr. Zhao says. “Since these odor bottles are prepared in semi-log dilution, this means that those people detect the odor at over 10 times lower in concentration after putting on the smell aids.”

For patients who did have smell loss, their scores on the NIH odor identification test improved, especially in the group who hadn’t experienced COVID-19-related smell loss. The effect size was 1.065 (95% CI: 0.190-1.940).

“These patients can detect and correctly identify on average one more odor, after wearing the smell aids. For COVID long haulers, only the nasal plug remains effective,” Dr. Zhao says.

Participants who had very sensitive senses of smell experienced some improvement with the smell aids, but not much. Dr. Zhao notes that this makes sense.

“As an analogy, eyeglasses may significantly improve suboptimal vision but have little effect on perfect 20/20 vision.”

What study results mean for people experiencing smell loss

Existing treatments for what clinicians call long-term olfactory dysfunction, such as olfactory training and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections, are experimental or haven’t yet been proven effective.

This study shows that we might be able to improve someone’s sense of smell with non-invasive methods in people who have different types of anosmia or hyposmia. Next steps for scientists will be to improve the design and effectiveness of those methods.

“The smell aids have the potential to broadly help people who have olfactory loss or depend on smell for their careers, like chefs, perfumers and food and wine critics, and people who want to enrich the experience of enjoying food and fragrances,” Dr. Zhao says.

When you give to The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, you’re helping improve lives

We’re committed to making advancements in research, education and patient care that will have an impact throughout Ohio and the world.

Ways to Give