Kidney transplant recipient thriving without antirejection drugs due to innovative treatment

Bone marrow transplant procedure tested at Ohio State improves quality of life, other outcomes after organ transplantation.

Kyle Clark teared up as he made calls to his family from an intensive care unit at a hospital in China, where he’d been placed on dialysis.

The kidney disease he’d been managing for the past two decades had caught up with him 7,000 miles away from home.

“You need my kidney, it’s yours,” his mother had reassured him from Nevada. When he broke the news to his older brother, Kevin, in Ohio, he’d responded, “You’re probably going to need my kidney.”

Within months, Clark had left his post teaching English to Chinese kindergarteners and returned to the United States, optimistic that a kidney transplant would give him his life back.

Then he learned about the lifelong regimen of medications organ transplant recipients take to keep the body’s immune system from rejecting the donated organ. Called immunosuppressants, they weaken the immune system and can impair the body’s ability to fight off infections.

The prospect of a lifetime on these medicines cast a shadow over his optimism.

“That was one of the scariest things. I can last through dialysis for a few years, get a transplant,” Clark says. “But then, even after all that is said and done, there will never be ‘normal’ again, because now there’s all these new stresses and new worries.”

His hope returned when he discovered that The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center offered access to a research trial that would give him a chance to potentially stop taking the antirejection drugs after his kidney transplant.

A novel approach to kidney transplant

He’d undergo not just the kidney transplant, but also a peripheral blood stem cell transplant — also known as a bone marrow transplant — from the same donor. The goal was to create a new immune system similar to that of his kidney donor to minimize the risk of rejection.

It wasn’t going to be easy, but Clark was willing.

“It’s 100%, in my mind, worth it: a few weeks of being down in the dumps, for years and years of freedom from immunosuppression. I think it’s an easy decision,” Clark says.

“And even if it doesn’t work for me individually, knowing that it helps people in my situation years down the road, that’s kind of a cool thing to be a part of.”

While at Ohio State, he received his brother’s donated kidney as well as his brother’s bone marrow through donated peripheral blood stem cells.

“That was the hardest part,” he said in February 2023 from a hospital recliner. “If I can make it through that, then from here on, it may not be smooth sailing, but I know I can make it through whatever’s next.”

A procedure that could change the future of organ transplants

Antirejection medications are necessary after every organ transplant because the recipient’s immune system views the new organ as foreign and tries to destroy it.

Immunosuppressant medications keep the immune system at bay, but they come with many possible drawbacks, including risk of infections, some cancers and scarring of the new kidney, as well as diabetes, high blood pressure and digestive issues.

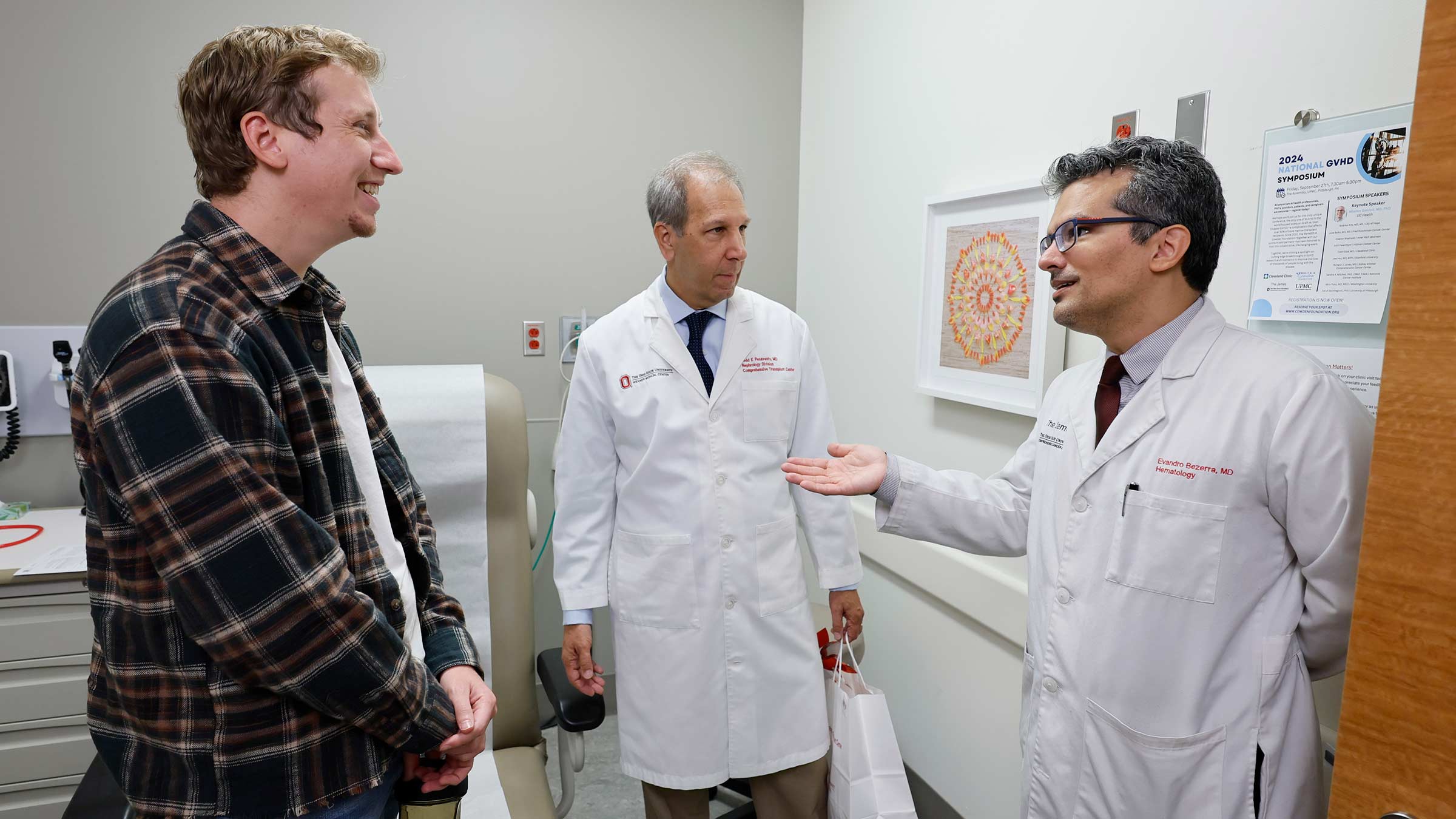

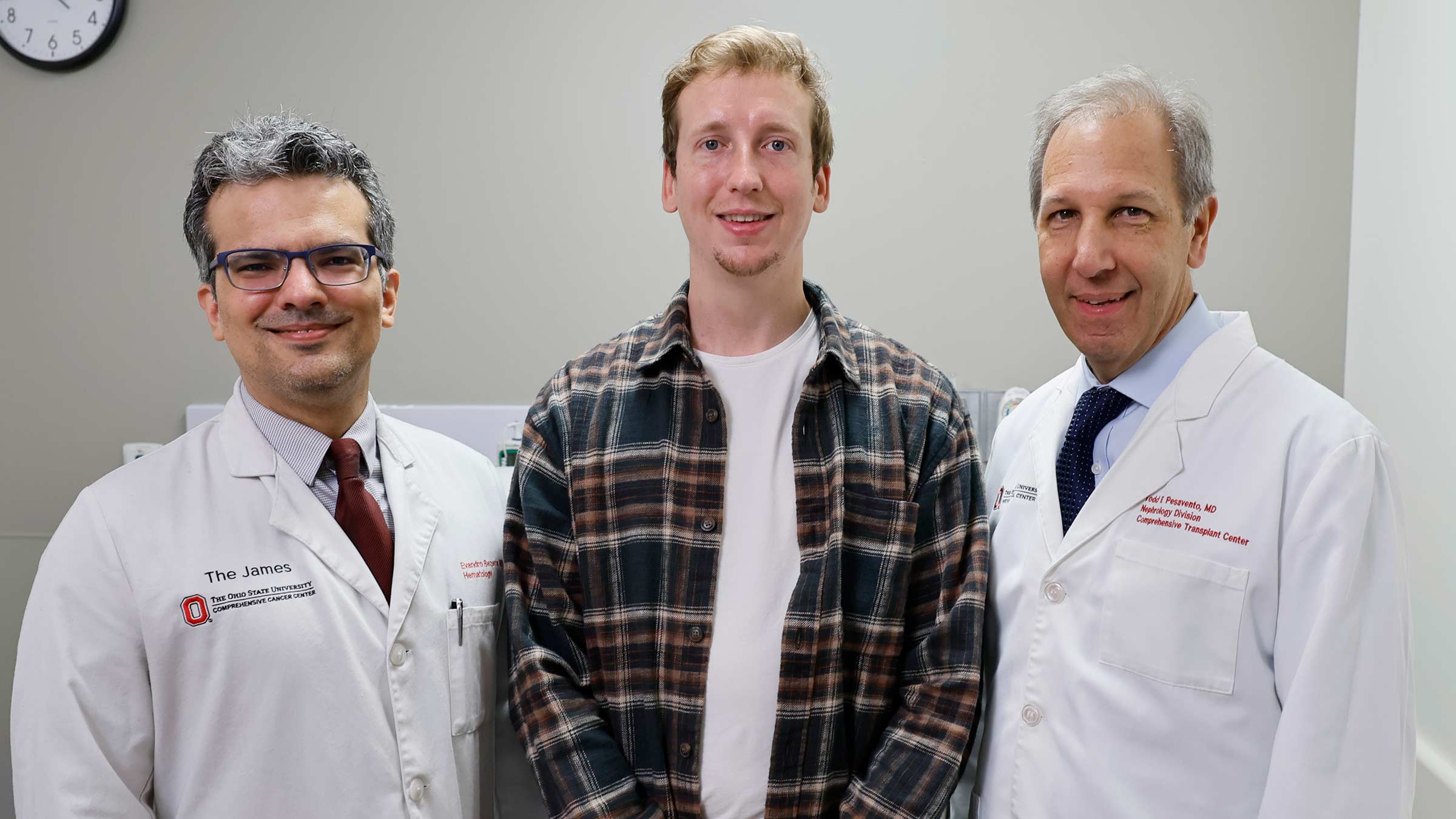

The goal of Clark’s bone marrow transplant was to pass along a significant part of his brother’s immune system to minimize the risk of kidney rejection, says hematologist Evandro Bezerra, MD.

While still in the experimental stage, the outcome of procedures like Clark’s could change the future of organ transplant care.

“The lessons that we learn from this hopefully will be extended to all organs — heart, lung, liver, pancreas and kidney,” says Todd Pesavento, MD, medical director for Ohio State’s kidney transplant program and lead investigator for this research trial at the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center.

“In the next 10 years, there are going to be so many advancements. It’s really phenomenal.”

Life-changing organ donation

Kyle Clark’s older brother, Kevin Clark, had volunteered to be his donor when their mother was unable to give stem cells for the bone marrow transplant.

“He wasn’t the little brother I had growing up. I felt like, as a big brother, this is my opportunity to step up,” said Kevin Clark, then 31, as he recovered from kidney-donation surgery at the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center.

Kevin Clark went on to say that it was worth it to hear the excitement in his brother’s voice and see how much better he looked after the transplant.

Kevin Clark was also looking forward to asking his brother to grab a 12-pack of beer and something to eat and watch a football game without having to second-guess it. And he said it would be a relief for both brothers, who share a home in Columbus, to live without boxes of dialysis supplies stacked to the ceiling in a spare room.

Kyle Clark says he hopes his older brother’s kindness encourages others to consider living kidney and bone marrow donation.

“I don’t think words can describe how thankful you are, because that is life-changing. It was a commitment for him, a sacrifice for him, and some people aren’t as lucky to have a brother that steps up,” Kyle Clark says.

Checking all the boxes

After his surgery, doctors initially placed Kyle Clark on the antirejection drugs, along with other medications to help control side effects. He recalls about 10 bottles of pills in his medicine cabinet, a daily chore to keep track of the routine and the threat of losing the kidney if he missed a dose.

There was also the stress of managing a suppressed immune system, worrying about exposure to illnesses and limiting activities and travel.

Doctors tapered the medications over 16 months.

Organ rejection isn’t the only concern. With a bone marrow transplant, the body’s immune system is wiped out to prepare it to receive healthy cells, so Clark was also at high risk of infection as he built up the new immune system that would accept the kidney.

There was also a possibility that the donated immune cells could view Clark’s body as foreign and attack, leading to a life-threatening complication, graft-versus-host disease (GvHD).

As Clark’s medical team continues to monitor his response to the kidney and his new hybrid immune system, Dr. Pesavento and Dr. Bezerra say he has excellent kidney function and has avoided GvHD and any major infections.

Clark says his care team made sure to check every box, having him talk to various experts if there was ever a concern.

“Luckily, there was never something that was a huge issue, but it did make me feel well cared for,” he says. “The people I’ve worked with have been amazing. I’ve felt like I was treated like a VIP patient.”

Right: Kevin Clark following surgery to donate his kidney.

A massive team

Clark’s is the only such organ transplant performed at Ohio State, as part of the FREEDOM-1 study, which has since ended.

“It took more than a village, it took a city to make this happen,” says Claire Carlin, CCRP, senior clinical research coordinator at the Center for Clinical Research Management at The Ohio State University College of Medicine.

“We had to tap into so many experts. We were building the bridges, and we were walking across them, we truly were. But there was always a resource who knew exactly how to do it,” Carlin says.

Carlin says the project involved massive teams from two of Ohio State’s powerhouse programs with long histories.

Ohio State’s organ transplant program began in 1967, and the Comprehensive Transplant Center continues to drive innovation, performing more than 600 solid organ transplants each year. To date, more than 13,250 transplants have been performed, of which over 8,600 have been kidneys.

The first bone marrow transplant was performed at Ohio State more than 40 years ago, and the Blood and Marrow Transplant Program at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute (OSUCCC – James) is consistently at the forefront of treatment advances.

The collaboration between the teams was crucial, Carlin says.

Because Clark’s bone marrow transplant left his immune system depleted, his postsurgery care was handled at the OSUCCC – James. The hospital features a special unit designed to prevent infection and cancer teams skilled in caring for patients after bone marrow transplants.

Nurses from both the organ transplant and cancer teams, who usually don’t work together, volunteered to cross-train so they could participate in the trial, with organ transplant nurses spending time at the OSUCCC – James to ensure Clark received needed, specialized care from both teams.

It hit close to home for Victoria Johnson, BSN, RN. She has kidney disease, and her mother is a kidney transplant recipient.

“I’d never even heard of anything like this being possible,” says Johnson, who was one of two kidney transplant nurses who cared for Kyle immediately after his surgery. “It’s kind of cool to see what the future holds. This could be me down the line.”

Kelsie Ulliman, APRN, at the OSUCCC – James, says nurses are often involved in novel research, but felt this experience was especially interesting because they were able to work with different teams.

“What we do at The James and Ohio State is simply incredible,” adds Ashley Mandrell, BSN, RN, OCN. “To collaborate with the kidney transplant team and their nurses’ willingness to come assist us speaks volumes to the culture and support.”

Right: Brothers Kevin and Kyle Clark enjoyed sushi to celebrate when Kyle stopped taking immunosuppressant medications.

Advancing science for patients

Dr. Pesavento says it was gratifying to see Clark improve after the transplant and continue to thrive as he stopped taking antirejection medications.

“He’s got his life back. He takes one blood pressure pill and one medicine to prevent a virus. That’s unheard of for transplant patients,” Dr. Pesavento says.

He’s optimistic that Clark’s transplant will serve him longer than the average living donor kidney transplant, which lasts about 15 to 20 years.

“One of the drugs that is very effective at preventing rejection has the undesirable side effect of causing long-term scarring in the transplant. If we can eliminate that, the kidney should last almost indefinitely,” he says.

Dr. Pesavento says such results are worth the time and effort that goes into making trials a success.

“That’s why we all do this. We want to have our patients get better and we want to advance science so we can help more people in the future,” he says.

Ready to learn more about living kidney donation?

We've got all the information you need to start the process.

Learn more