Treating stress during pregnancy to improve outcomes for babies

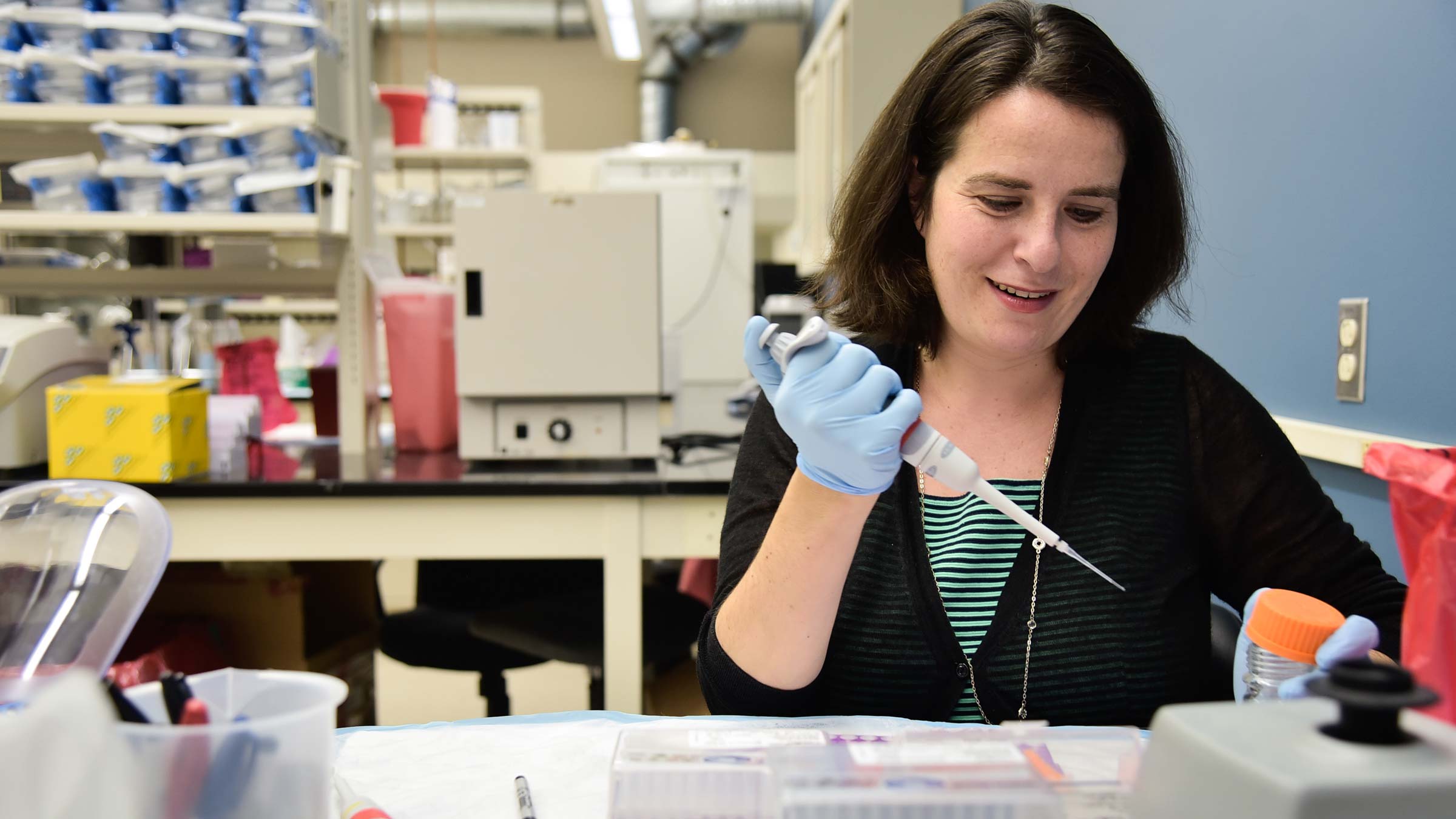

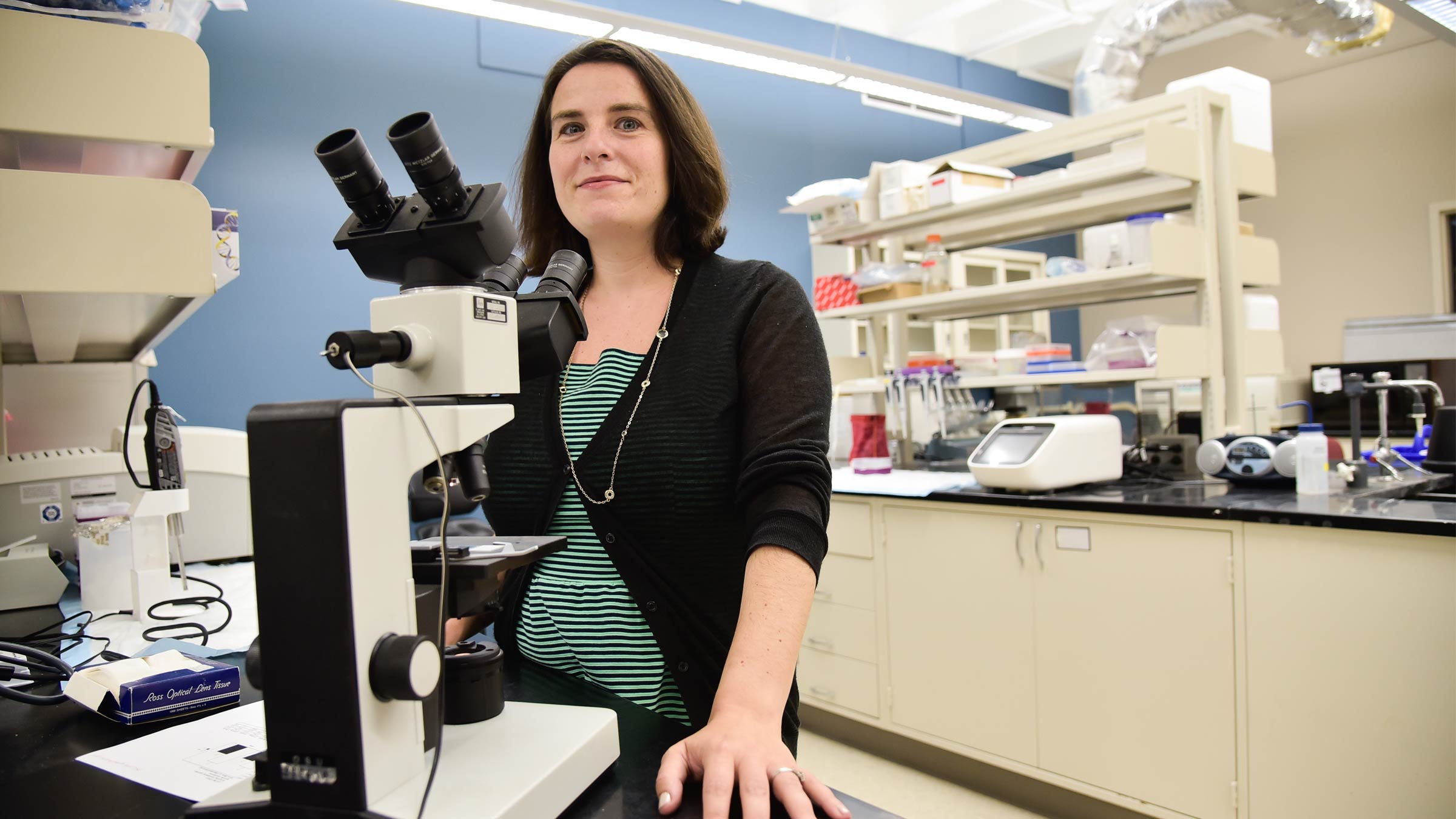

Psychiatrist and researcher Tamar Gur, MD, PhD, is exploring personalized treatments tailored to each patient’s microbiome.

As a psychiatrist treating prenatal and perinatal patients, Tamar Gur, MD, PhD, often works with pregnant people who previously experienced a miscarriage, stillbirth or infant loss. The stress is constant, and they are surrounded by reminders of their loss. “You go to the same doctor, have the same tests and feel similar. But you’re hoping for a different outcome. It’s so triggering,” Dr. Gur says.

Witnessing this and knowing how stress negatively affects the microbiome and immune system of the patient and their baby leaves Dr. Gur wishing she had more tools.

“We have got to do something more helpful during pregnancy,” Dr. Gur says.

For Dr. Gur, associate professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health, Neuroscience, and Obstetrics and Gynecology at The Ohio State University College of Medicine, these are the cases that also prove to be motivating.

Dr. Gur uses therapy and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) to help with stress, anxiety and depression. SSRIs are a class of medications commonly used to treat mental health conditions by increasing the amount of the neurotransmitter serotonin in the brain. However, it’s well known among psychiatrists that these medications haven’t changed in decades. And they’re certainly not patient-specific.

In the laboratory of Tamar Gur, member of the Dorothy M. Davis Heart and Lung Research Institute on The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center campus, her team’s research will expand the psychiatric toolkit exponentially. Dr. Gur studies how the microbiome, made up of microorganisms that reside in and on the human body, affects mood and behavior. With therapies targeted at an individual’s biome, Gur hopes to offer patients customized treatment within a few years.

“If a pregnant patient comes in experiencing something stress-inducing such as a move or the loss of a loved one, I hope to offer a microbiome-based treatment that prevents some of the negative stress on the baby,” Dr. Gur says.

Finding a calling in psychiatry

Dr. Gur is the daughter of a physician-scientist. She learned to talk when her parents worked on a large grant, making “proposal” one of her earliest words. Like her mother, Dr. Gur decided psychiatry was her calling. In addition to her medical degree, she earned a PhD in neuroscience, studying how neurons are formed in the brain and how chronic administration of antidepressants can impact those neurons.

It wasn’t until her medical residency that Dr. Gur focused on prenatal and perinatal patients. She was drawn to their resilience and determination.

“Pregnant people are so committed to improving because they aren’t only improving themselves, they’re also getting better for their babies,” Dr. Gur says.

While balancing clinical care with laboratory research is challenging, Dr. Gur says the two are inherently intertwined. “I couldn’t imagine being a physician without also creating knowledge. But science has a delayed gratification, and there’s an immense reward in helping people,” she says.

Today, Dr. Gur studies the microbiomes of pregnant people, determining how perinatal stress impacts offspring development. By identifying the consequences of exposure to prenatal stress, Dr. Gur hopes to harness specific beneficial microbes. Ultimately, the goal is to provide patient-specific medication that helps the pregnant person while also benefiting the offspring. “As a society, we pay such scrutiny to what pregnant people put in their mouths — from sushi to caffeine, but there’s a lack of mental health interventions that can benefit both the pregnant person and the baby.”

Stress during pregnancy and the implications for mental health

Dr. Gur is most interested in how early exposure to stress affects health across the lifespan. “We know from large population studies that children exposed to natural disasters in utero have an increased risk in developing a wide range of psychiatric disorders,” Dr. Gur says.

Stress changes a person’s community of microbes, which can cause inflammation. For a pregnant person, this may also affect the fetus by reducing anti-inflammatory microbes.

By testing the placentas of both mice and clinical patients, the Gur Laboratory team has found stress reduces specific microbes in the gut that are beneficial to health. For example, microbes that help metabolize tryptophan — commonly known for making you tired after eating turkey — decrease with stress. Tryptophan is one of nine essential proteins the body needs for overall health. It’s a crucial building block for newborn brain development, regulating food intake, feeling full and sleep rhythm. “We added it to our mouse model and were able to reverse several key negative changes in the mother’s social behavior and reversed the increased inflammation in the offspring’s brain,” Dr. Gur says.

The pandemic was fertile ground for researching how stress impacts pregnant people and babies. The Gur Lab was studying stress symptoms in pregnant people’s microbiome samples when the pandemic hit. Once they resumed research, they found profound changes in the microbiome and inflammation.

Taking the blame out of perinatal stress

Dr. Gur knows firsthand that stress during pregnancy is unavoidable even in the best circumstances. As a mom of four, she had babies during medical school, residency, her first year on faculty and at age 40. “I’m invested in figuring out how stress exposure during pregnancy impacts infants’ brains and overall health,” Dr. Gur says.

With parenting, patients, research and leadership work, most of Dr. Gur’s day is spent juggling. “If I have disappointing research results, a challenging meeting or something that depletes me, I have to center myself because that’s not the energy to bring into the clinic — especially when your clinic involves such sensitive topics,” Dr. Gur says.

To stay motivated in both her research and clinical work, Dr. Gur draws inspiration from patients. “The things we go through as humans while remaining resilient are inspiring. Watching people persevere through the unimaginable is a privilege,” Dr. Gur says.

As a clinician and researcher, Dr. Gur says she can’t emphasize enough that stress during pregnancy mustn’t be blamed on the mother. “This is a call to support women and families during pregnancy and postpartum.”

Developing patient-specific psychiatric treatment to treat stress during pregnancy

Dr. Gur has high hopes for helping pregnant people — including her patients — in the near future. She and her team are only beginning to understand how the microbiome and inflammation during pregnancy impact disease processes, but results in mouse models have proved to be positive.

“We’re learning how to set someone up for a healthy lifespan. This work will be important, exciting and helpful,” Dr. Gur says.