Out-of-the-box immunotherapy treatment holds promise for breast cancer

Breast cancer researcher tests new way to harness the body’s natural immune system.

The first time Margaret Gatti-Mays, MD, MPH, applied to medical school, she received 21 rejections. A few cited her lack of research experience, so she pursued a master’s degree and reapplied. From that experience, Dr. Gatti-Mays gained two things: persistence and a passion for research.

Today, as a physician-scientist in medical oncology, Dr. Gatti-Mays says, “It was super important that I didn’t get into medical school that first time around because I don’t think I’d be doing what I’m doing today, and I don’t think I’d be as happy as I am.”

Developing a new way to treat breast cancer

Her dedication to research and a desire to find better ways to help her patients led Dr. Gatti-Mays to a research collaboration with Dean Lee, MD, PhD, from Nationwide Children’s Hospital.

The two met in 2020 to consider how Dr. Lee’s immuno-oncology research could be applied to metastatic breast cancer treatment — breast cancer that spreads to other areas of the body. They riffed off each other’s ideas until Dr. Gatti-Mays developed an out-of-the-box immuno-oncology treatment that is now in its first clinical trial.

The new immunotherapy approach uses naturally occurring immune cells called natural killer (NK) cells from healthy donors that are modified to resist cancer cells’ attempts to destroy them. Those donor NK cells have the potential to fight against metastatic cancer and stimulate the patient’s own immune system to do the same.

Dr. Gatti-Mays hopes the novel treatment, available only at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute (OSUCCC – James), could become a better option for patients with advanced metastatic breast cancer.

Today, four years after that original meeting, two patients at The James have become the first breast cancer patients anywhere in the world to receive this immunotherapy combination in a clinical trial.

Career launched together with immuno-oncology

When Dr. Gatti-Mays decided to become an oncologist, chemotherapy was the principal therapy for breast cancer. That changed soon after she graduated from medical school, when a game-changing drug called ipilimumab was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as the first immunotherapy treatment.

This marked a radical shift in cancer research and treatment when doctors could begin to imagine one day curing even stage 4 cancer.

“The shift to treating some cancers like a chronic disease really came with immunotherapy,” Dr. Gatti-Mays says.

Today, only 13 years later, Dr. Gatti-Mays has lengthy discussions with patients diagnosed with breast cancer because there are so many treatment options, including immunotherapy combinations. “I find a lot of hope when I reflect back because so much has changed in such a short time,” Dr. Gatti-Mays says.

The promise and challenges of immunotherapy

Immuno-oncology harnesses and builds on the body’s natural defenses against cancer. Because cancer cells destroy healthy immune cells, immuno-oncology focuses on strengthening the immune system rather than poisoning the cancer. This is unlike other cancer-centric strategies like surgery, chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

“Cancer is a graveyard for immune cells, but you can actually program those cells so that they will not die and will stay active,” says Zihai Li, MD, PhD, the founding director of the Pelotonia Institute for Immuno-Oncology at The James, who recruited Dr. Gatti-Mays to join the research institute five years ago.

Jeffrey Schlom, PhD, a senior investigator at the National Institutes of Health’s Center for Immuno-Oncology and a mentor to Dr. Gatti-Mays, has researched immuno-oncology for decades. “When I approached physicians about wanting to do a clinical trial, they’d laugh and call us cowboys. Everyone said immunotherapy doesn’t work,” he says.

Today, not only does immunotherapy work to treat some patients’ cancer successfully, but it also gives researchers hope for one day ending cancer. “The field is moving quickly, and every day more agents are being approved by the FDA,” says Dr. Schlom.

- Unlike chemotherapy or radiation therapy, immunotherapy tends to have a more lasting effect on cancer.

- Cancer cells are very good at mutating, but immune cells have memory and will destroy cancer cells that reoccur.

- Immunotherapy is more targeted and tends to be less toxic than other therapies.

“Some patients will have maybe a 20%-50% reduction in their tumors, and it stays like that for 10 years or more,” Dr. Schlom says.

Still, immuno-oncology research has a ways to go. Only about 20% of patients respond to immunotherapy. “This is where there’s a need for more sophisticated approaches, like what Dr. Gatti-Mays is doing,” Dr. Schlom says.

Dr. Gatti-Mays credits Dr. Schlom as a source for her ambition to think out of the box in research. Her goal is to help the 80% of patients who don’t respond to existing immunotherapy treatment — especially those who have solid tumors, like breast cancer. “Dr. Schlom taught me to think critically about the science, to bring that knowledge to the clinic and that it’s only ‘crazy’ until you do it,” she says.

Using ‘natural killer’ cells to fight breast cancer

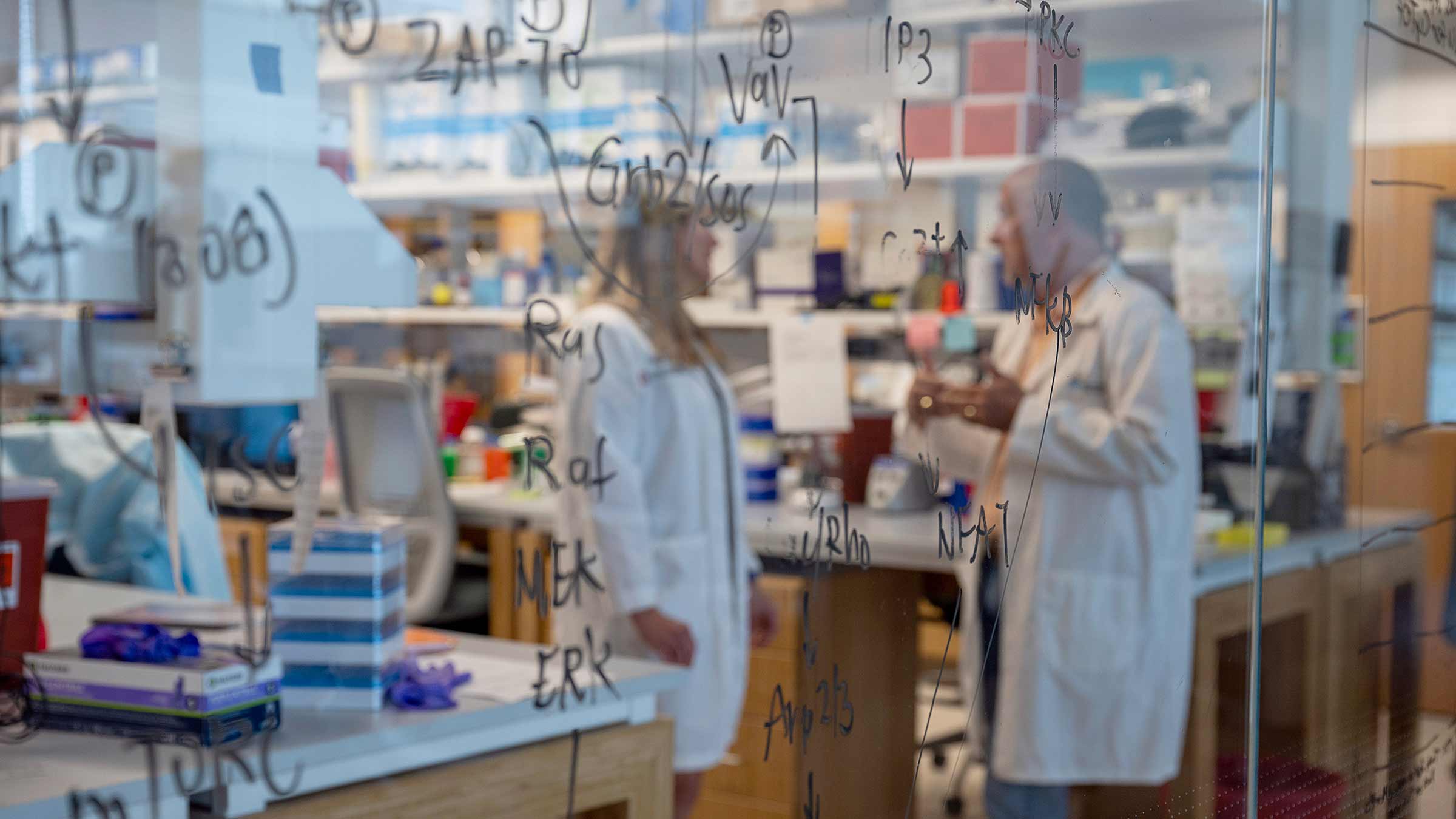

The body’s immune system has multiple players, including natural killer (NK) cells. NK cells have a rapid attack response to cells that don’t belong, like virus-infected cells or cancer cells.

The problem is that cancer cells excel at blocking or destroying the body’s NK cells. Powerful chemotherapy drugs that attack cancer cells also affect healthy ones, including NK cells.

Researchers in the Lee Lab at Nationwide Children’s Hospital developed a method to grow and activate large numbers of NK cells from healthy donors to enhance their ability to target and destroy cancer cells. The cells were provided from volunteer donors and were collected by the National Marrow Donor Program (formerly Be the Match). The research team is testing ways to use this “sea of NK cells” to target many types of cancer.

Dr. Gatti-Mays worked with Dr. Lee, who had developed a way to make NK cells resistant to a specific chemical secreted by cancer cells called transforming growth factor beta (TGF beta), that normally renders healthy immune cells ineffective at killing cancer cells. Cancer cells express this molecule to protect themselves.

While working with Dr. Schlom, Dr. Gatti-Mays focused on the role of TGF beta in breast cancer and brought that interest with her to Ohio State. “Because we know patients’ own immune cells aren’t working, we’re giving them someone else’s that are then resistant to TGF beta,” Dr. Gatti-Mays says.

This process takes time, and cancer cells multiply quickly, so Dr. Gatti-Mays and Dr. Lee, with the help of the Cell Therapy Lab at Ohio State, used the healthy donor cells to create a large bank of ready-to-use cells. Dr. Gatti-Mays combined the modified cells in a one-two punch with chemotherapy and an antibody called naxitimab.

“The intent of the combination is to use chemotherapy to reduce some of the bulk of the tumor and stress out the cancer cells so they’re more sensitive to NK cells, and then add the antibody for even more specific targeting,” Dr. Lee says.

The treatment is unlike any other immunotherapy because the NK cells are modified to do a specific job and combined with chemotherapy to become even more effective.

Dr. Zihai Li likens this breast cancer treatment to a war. “This NK cell approach is like a Navy Seal, where you have to use different ways of attack to deal with a really tough enemy. This combination of multiple cell therapy forces has the kind of precision to deal with a deadly enemy,” he says.

Whether this approach will be a game changer for breast cancer is yet to be determined, but either way, Dr. Li is excited about the concept and the clinical trial. “You have to be the pioneer and take a risk, and you may even fail. But it’s through this kind of creative, painstaking research and passionate drive that we move the field forward,” he says.

Next steps in immunotherapy research for breast cancer

The goal of this first clinical trial, which is supported by Pelotonia and the Stefanie Spielman Fund for Breast Cancer Research, is to test the protocol’s safety. The next step will be to enroll more patients to determine if the treatment is effective.

The treatment could also have broader applications for other types of cancer. “These natural killer cells aren’t tumor-specific, because they’re from healthy patients. They have tremendous potential to transcend tumors by giving patients back working immune cells,” Dr. Gatti-Mays says.

If the trial is not effective, scientists will learn from that, too. Dr. Gatti-Mays, who releases stress by powering through a tough run, says researching cancer is a long game. “The way I look at cancer treatment today, especially in the metastatic setting, is that it’s a marathon.”

The patients Dr. Gatti-Mays treats in her clinic drive her to keep pushing the science.

“When you have a person in front of you and you know their family, friends and their story, there’s no better motivator to push through and do the things that are outside the box,” she says.

If you’re lucky, says Dr. Gatti-Mays, the science you’re passionate about sometimes directly correlates to giving patients more time with their families for more milestones like vacations, graduations, birthday parties and grandkids. “It’s these shared life moments that make my chosen career as a physician-scientist rewarding. It’s an incredible time to be in oncology because there's been so much progress and so much hope,” she says.

While Dr. Gatti-Mays’ patients depend on her, colleagues are rooting for her. “I’m bullish. We have to support each other, and eventually, we’re going to win this war against cancer,” Dr. Li says.

Your support fuels our vision to create a cancer-free world

Your support of cancer care and pioneering research at Ohio State can make a difference in the lives of today’s patients while supporting our work to improve treatment and reduce cases tomorrow.

Ways to Give