How new pancreatic cancer research strengthens hope for patients

Ohio State’s new director of surgical oncology sees a duty to study the most challenging diseases — such as pancreatic cancer — to improve outcomes.

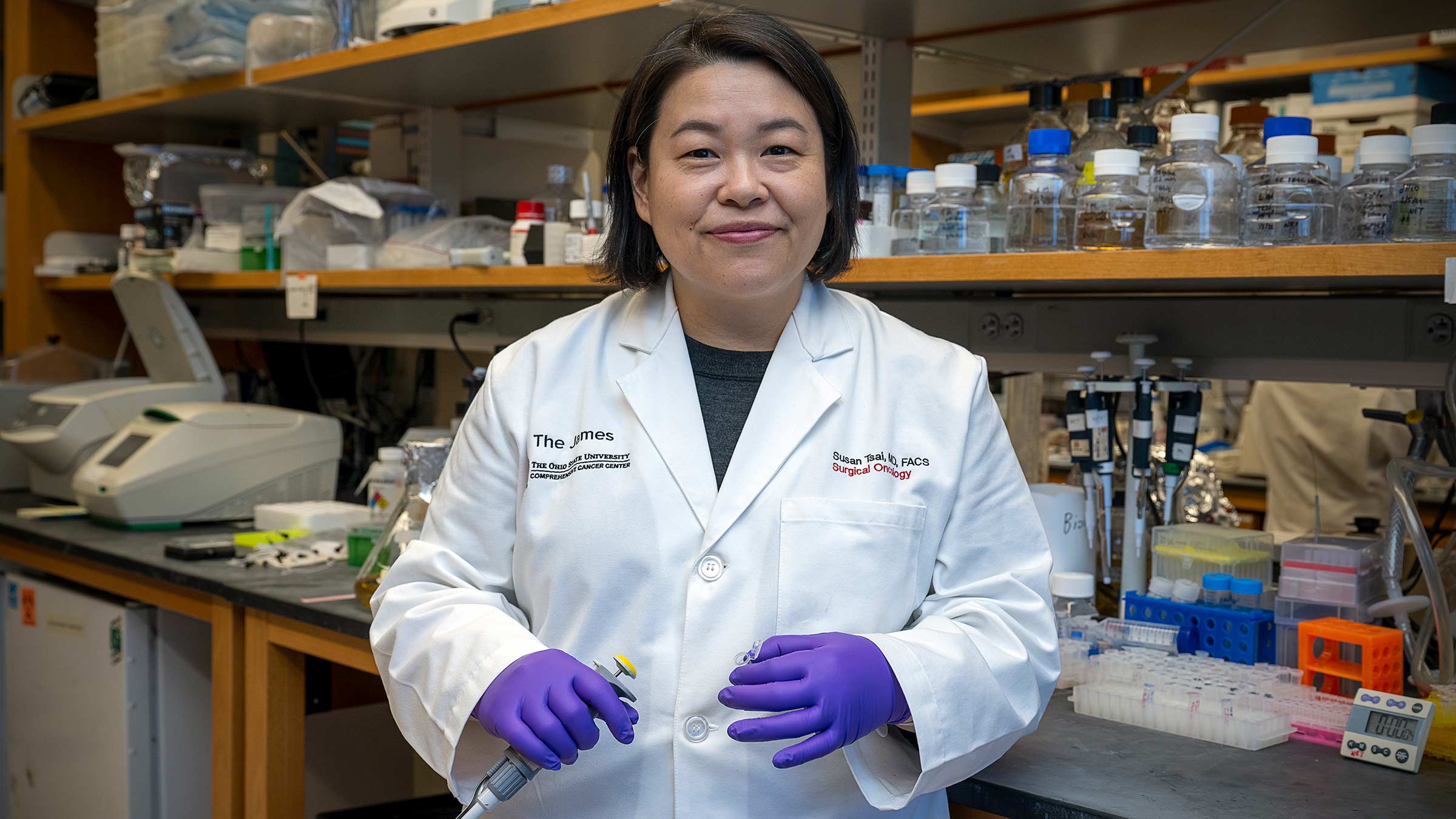

Surgical oncologist Susan Tsai, MD, MHS, (view profile) knows what many patients are thinking when diagnosed with pancreatic cancer.

“In general, the narrative is very grim, and when patients come through the door for treatment, sometimes they think they don’t have much time,” says Dr. Tsai, a pancreatic cancer specialist and researcher at The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center – Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital and Richard J. Solove Research Institute (OSUCCC – James).

American Cancer Society (ACS) statistics justify their fears: Although pancreatic cancer accounts for only 3% of cancer diagnoses in the United States, it accounts for 7% of cancer deaths and has one of the lowest long-term survival rates among major cancer types.

But Dr. Tsai, who came from the Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW) to direct the Division of Surgical Oncology at Ohio State, points out that the overall five-year survival rate of 12% has risen from a dismal 5-6% over the past few decades — a hopeful improvement.

“We still have a long way to go, but I think we’ve made important incremental advancements,” she says. “I feel we have an obligation to focus on diseases that are really challenging to treat, where we can make the biggest improvements for patients.”

Studying clues within the blood to better understand how pancreatic cancer can be treated

Dr. Tsai, who holds the Dr. Arthur G. and Mildred C. James – Richard J. Solove Chair in Surgical Oncology, joins several top-tier medical scientists at Ohio State who are studying cancer of the pancreas, a gland behind the stomach that sends digestive juices into the small intestine to help break down food. The pancreas also releases hormones that help control blood-sugar levels.

Part of her research focuses on finding and examining blood-based biomarkers, or clues within a patient’s blood about the presence and extent of cancer.

Dr. Tsai says a standard of cancer care is to target tumors with chemotherapy and radiation and to rely on radiographic imaging to demonstrate response to treatment, but for pancreatic cancer that process can be challenging.

“If you remove pancreatic cancer from the body and look at it under a microscope,” she explains, “most of what you see is not cancer but scar tissue, or the body’s reaction to cancer. So it may not look like much has changed with treatment.”

The tumor might be getting smaller, she says, but the scar tissue remains about the same, hindering doctors’ ability to correctly estimate whether treatment is working.

Dr. Tsai says that’s why it’s important — especially in pancreatic cancer — for doctors to monitor biomarkers in the blood “so they can see a more dynamic change and better understand when treatments are effective, and change therapies if necessary.”

She also leads clinical trials that study the genetic makeup of pancreatic tumors so clinicians can target treatments toward stopping each patient’s biologically unique cancer. This is known as molecular profiling to guide therapy, a practice commonly used in other cancers.

In line with this work, she’s leading a National Cancer Institute (NCI)-funded clinical trial aimed at examining both tumor and stroma (surrounding tissue) to understand and predict treatment response among patients with pancreatic cancer.

“For pancreas cancer, we’re just beginning to understand how to use molecular profiling for treatment, and that’s what we’re doing in this clinical trial,” she says, explaining that it will help personalize treatment for patients better than ever before.

Dr. Tsai also has received grant funding for two additional clinical trials that she hopes to open soon. One of those also will focus on changing chemotherapy based on a blood-based biomarker.

Finding meaning in relationships with patients

It’s exciting work for a medical scientist who has always loved learning but who, when she was growing up in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and later when she was majoring in chemistry at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, had no dreams of becoming a surgeon.

“I don’t think that was even on my radar,” says Dr. Tsai, the daughter of Taiwanese immigrants who ran an Asian grocery and restaurant in Ann Arbor after they arrived in the United States. “My professional development has been more of a discovery process.”

In college, she entered pre-med studies later than other students, reaching her decision after realizing how much she liked caring for people.

“I thought maybe I’d be a pediatrician, because I think everyone has a fondness for kids,” she says. “But I ended up doing surgery because I loved the immediacy of it: You face a medical problem that you can usually correct rather quickly. That led me to my surgical residency (at the University of Michigan, where she had also earned her MD), and I enjoyed every aspect of it.”

During residency, she completed a clinical research fellowship at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) that drew her to oncology.

“Every patient treated at the NCI is on a clinical trial, and they are usually end-stage patients,” Dr. Tsai says. “When I started there, Dr. Steve Rosenberg, who still heads up the NCI surgery branch, told the trainees there that probably 90% of the people we’d take care of at the NCI would die because they were on their third or fourth line of therapy and had very advanced disease.

“But during that period, I saw an opportunity to translate research into effective clinical trials, and also to develop meaningful long-term relationships with patients. In oncology, you get to share a journey with patients through some of the most difficult times in their life. It’s a transformative experience for the patient, but we’re privileged to witness it as well, and we also can be transformed by it.”

Eager to expand her work beyond pancreatic cancer

Dr. Tsai enjoyed her 13 years at MCW and plans to further her work while at Ohio State.

“What attracted me here was the exceptionally talented people in the Division of Surgical Oncology,” she says. “Many of them are on a similar journey that I’ve already had as a physician-scientist, so I recognize some of their struggles and feel that, as division director, I can offer mentorship and support.”

She hopes her own research will continue to advance pancreatic cancer research and treatment. “We cannot really look for cures without understanding the biology of this disease and how to deliver better therapeutics. Much more research is needed.”

She also sees her new role at Ohio State as a chance to expand her work to multiple disease sites beyond the pancreas, ever widening her research and patient care.

Putting patients forever first

Dr. Tsai’s determination is fueled by her patients. “I recognize that I’m taking care of people who are going through a tough diagnosis, and that every day I get to see their amazing resiliency and the strength of the human spirit.”

She’s too busy to have given much thought to a career legacy, but she hopes her work with colleagues in surgery and other disciplines will lead to beneficial changes in clinical care — for cancer patients in general, but more specifically for those with pancreatic cancer, for whom she has “a special softness.”

“I’d like us to be remembered for how we put all of our patients first, whether in their treatment or in helping them cope with their disease,” she says, “and that there is growing hope associated with a pancreatic cancer diagnosis, instead of what many people may feel now is a death sentence.”

Your support fuels our vision to create a cancer-free world

Your support of cancer care and pioneering research at Ohio State can make a difference in the lives of today’s patients while supporting our work to improve treatment and reduce cases tomorrow.

Give Today