Back on the trails after a lifesaving double lung transplant

After lung disease and transplant, Ann Sidesinger is determined to honor her organ donor’s precious gift.

Ann Sidesinger inhales deeply, allowing the crisp air to fill her nose and flow into her lungs, causing her chest to rise and fall.

“These aren’t my lungs,” says Sidesinger, lightly patting her chest.

Most people breathe without thinking. But for Sidesinger, 69, each breath is a gift from a woman she’ll never meet.

She savors every breath, smiles and silently exhales.

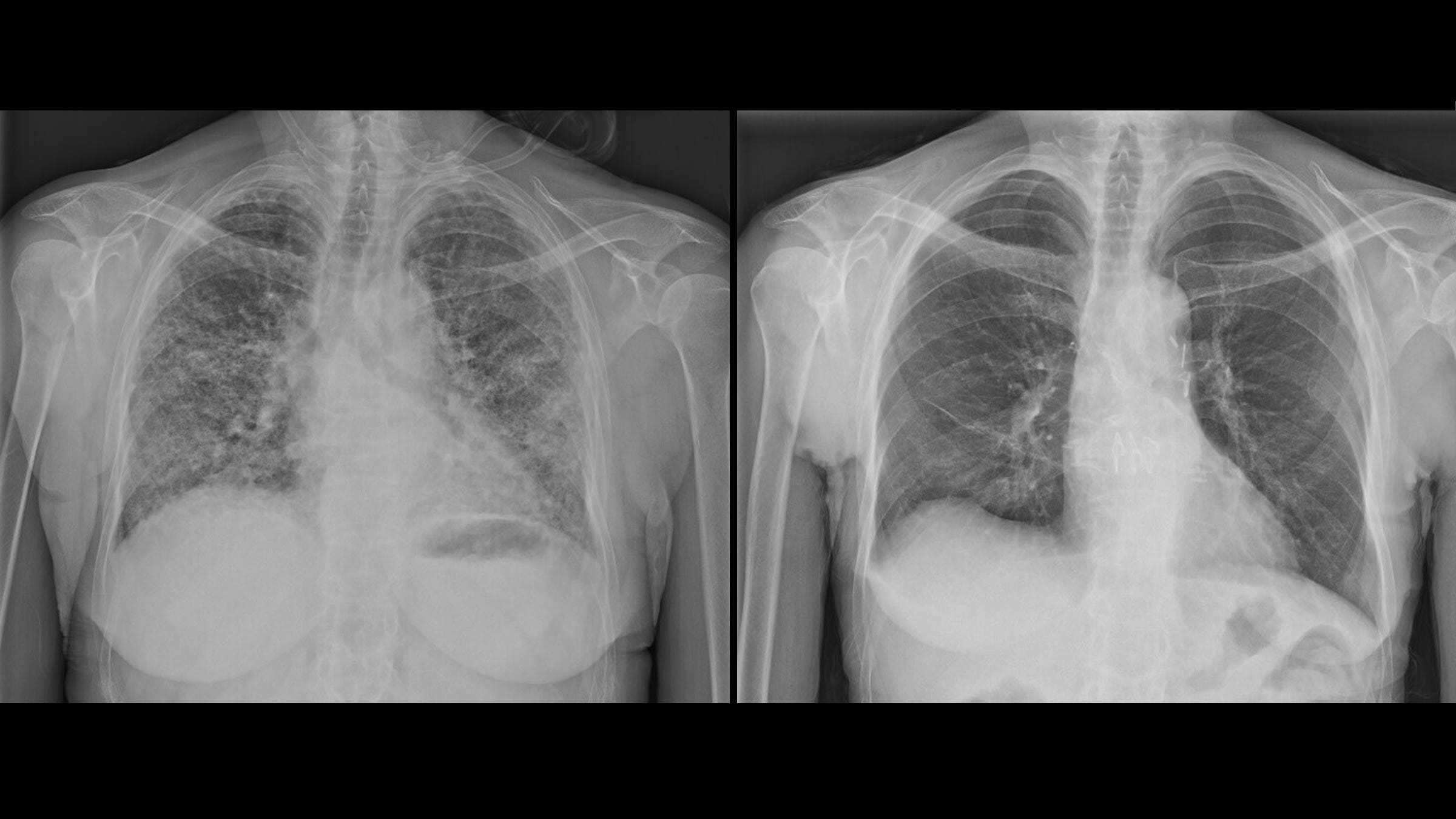

In 2015, Sidesinger was diagnosed with interstitial lung disease (pulmonary fibrosis and bronchiectasis), which scars and thickens the lung tissue, ultimately hindering the ability to breathe.

Even when she took deep breaths, her chest wouldn’t rise or fall. At her sickest, she couldn’t even walk 10 feet.

“She really deteriorated to the point of needing oxygen at rest,” says Matthew Henn, MD, the cardiothoracic surgeon who completed Sidesinger’s double lung transplant, one of more than 13,250 organ transplants completed at The Ohio State Comprehensive Transplant Center since 1967.

With lungs from a generous donor, and a hard-fought recovery, she can now breathe freely and return to her favorite pastime: hiking.

“I got some dynamic lungs,” she says. “They were a perfect match for me in every way.”

‘I can’t do this anymore.’

It’s unclear what caused Sidesinger’s condition. A former runner, she smoked for a few years in the 1970s but hasn’t smoked in 50 years and otherwise lives a healthy lifestyle.

After the diagnosis, it was a life of making adjustments.

Completing off-trail hikes once offered a great sense of accomplishment and a rush of endorphins.

“That blue sky and feeling of the fresh air against your skin . . . you just feel so alive and in sync with the earth,” she says.

But the hikes that were once challenging soon became impossible.

As her condition slowly progressed, her mobility and ability to breathe lessened.

Climbing the stairs each night to her bedroom became an enormous challenge. When it was time to head upstairs, she would turn the dial on her oxygen tank to maximum and quickly climb.

Once at the top, she would collapse on the floor.

“I would take a few minutes and have a pity party for myself,” she says. I can’t do this anymore. I can’t do it, she would think.

After contracting pneumonia during the winter of 2022, her health significantly worsened, and she was placed on the lung transplant wait list.

Even eating became a struggle because she was so short of breath.

She would sit near the window with her oxygen tank and stare out at the tree-lined street, watching people biking or walking dogs.

She wondered if she would be able to do those things again.

“I would think, ‘They’re so lucky,’” she says.

Waiting for the right match

Sidesinger’s pulmonologist spoke to her about considering a lung transplant at Ohio State.

“You can’t be too sick. You have to be healthy enough to have the surgery. That’s all I thought about. ‘I am going to be healthy enough for this transplant,’” Sidesinger says.

By their very nature, transplants can’t be scheduled in advance.

Transplant teams are on call 24/7 until an organ becomes available.

It’s possible a doctor whom you’ve never met before will be performing the transplant.

That’s what happened to Sidesinger and Dr. Henn.

“I met her the night before surgery and we talked about the details,” he says. “I’m brutally honest and we talk through all the risks that can happen. I give a commitment to them that we’re going to do our very best to get them through.”

When lungs become available, they’re matched with the patient’s blood type and body size.

A team from The Ohio State Comprehensive Transplant Center, including a pulmonologist and a surgeon, reviews the lungs to ensure they’re in good working condition, and then a separate surgical team evaluates the lungs prior to proceeding.

“I knew I was in good hands and I was at the right place. I was going to be OK,” Sidesinger says.

Uncommon challenges of lung transplants

Lungs pose unique challenges compared to other transplanted organs.

“Lungs are always exposed to the environment, unlike hearts or kidneys,” Dr. Henn explains. “Each breath exposes the lungs to external elements.”

Because of this, lung transplant recipients are more susceptible to acquiring infections and take extra precautions including increased handwashing and masking in crowds.

Sidesinger endured a long rehabilitation after her major transplant surgery, which she described as difficult.

“Sometimes patients have to learn how to breathe normally again,” Dr. Henn says.

While waiting for a transplant, the diaphragm and supporting muscles used for breathing can atrophy and don’t work very well, he says.

Sidesinger was released from the hospital 12 days after her surgery and sent home to work on exercising and moving.

“I didn’t want to do it. Not being able to breathe for so long, and then actually being able to breathe, I was out of rhythm. I actually thought I couldn’t breathe,” she says.

Her children, now adults, would take her on walks in her neighborhood. She tightly clung to them.

“I didn’t want to go. I was shaky,” she recalls.

One house down. Two houses down.

Two months after coming home, she walked two blocks away from her house alone to a nearby street. Then she walked back.

Feeling terrified, she clutched a small medal with the word “Faith” engraved on it.

“Ann was particularly motivated and always had a very positive attitude,” Dr. Henn says. “If any curveball was thrown her way, she took it in stride.”

A Buckeye for Life

Lung transplants aren’t a casual decision. They are an absolute last resort and a lifelong commitment.

When he began caring for transplant patients in 1993, prior to working at the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, David Nunley, MD, says one-year survival rate for patients after lung transplantation was about 60%.

“Now, that death rate is down to about 10% in the first year,” he says. “We’ve made incredible progress.”

While long-term survival after lung transplant is the goal and is certainly possible, the average survival rate after receiving a lung transplant drops to 50% five to seven years after transplantation.

This fall will mark three years for Sidesinger.

Even with a successful lung transplant, the journey is still fraught with challenges.

Sidesinger takes anti-rejection drugs daily that weaken her overall immune system. She still visits her medical team for check-ups every six months.

“You are definitely a patient for life at Ohio State. They watch you. They watch everything. I always do what I’m supposed to do. I go to all appointments. I stay active because I want to be healthy,” Sidesinger says.

She’s monitored closely with blood work and a pulmonary function test once a month.

“There’s literally hundreds of people that go into taking care of these patients, and we take a lot of pride in being part of that team,” Dr. Henn says. “We treat everybody as we would want to be treated.”

A gift of time

Sidesinger thinks about her donor. She knows it was a woman in her 50s who also lived in a large Midwestern city.

She wonders if her donor was athletic because the lungs she received have worked so well for her.

She has hiked in elevations up to 14,130 feet at Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado.

She never lost her breath.

“I was fine. My legs were sore. I wasn’t. My lungs were fine. How is that possible?” she says.

That’s not surprising, Dr. Nunley says.

“Her measured lung function has more than doubled and been maintained since the transplant. The quality of the lung tissue she now has allows her to enjoy those types of activities,” he says. “Ultimately, however, this is mostly made possible through the ‘power of organ donation.’ Without families willing to donate, none of this would happen.”

“I'm just thankful every day for everything because there isn’t anything I can’t do now. I'm back. I’m better than I ever was,” Sidesinger says.

Sidesinger wrote a letter to her donor’s family about one year after the transplant.

“I let them know how appreciative I am for this gift,” she says.

Sidesinger never heard back but may try reaching out again.

“I just always wonder about my donor,” she says.

The journey of organ transplantation brings together the darkest moments of loss and the hope of a new beginning.

“Organ transplant is one of those things where you take a really horrendous situation for the donor and their family,” Dr. Henn says. “And we can make something really good come out of that. We can help somebody who is perhaps at their worst possible moment and give them another chance at life.”