How have medical scientists at the OSUCCC – James contributed to these and other innovations in the “war on cancer” initiated by the National Cancer Act? Ohio State cancer experts can cite several examples.

Raphael E. Pollock, MD, PhD, FACS

The OSUCCC director ranks the development of drugs called Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors for treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) — the most common adult blood cancer — among the top instances of groundbreaking cancer innovation at Ohio State.

BTK is a signaling protein that is important for CLL cell proliferation and survival. Pollock says drugs such as ibrutinib and acalabrutinib that inhibit BTKs have revolutionized the treatment of CLL.

“Before their development, which occurred primarily here at Ohio State through the work of Dr. John Byrd, MD, and colleagues, treatment of CLL was based on non-specific chemotherapies with only a 35% to 40% response rate,” Pollock says.

“The BTK inhibitors have an 85% to 95% response rate, and a rate of overall survival that is nearly twice that of the earlier era.”

Pollock also notes Ohio State’s role in the study of microRNAs, as exemplified by the pioneering work of Carlo Croce, MD, a world-renowned medical scientist who came to Ohio State in 2004. Some of the world’s first scientific evidence of the genetic basis of cancer had come from Croce’s lab in the early 1980s, and his studies have continued at the OSUCCC – James.

Pollock says Croce and colleagues showed that supposedly non-coding microRNAs (i.e., RNAs that don’t encode a protein) — once thought to be functionless within the genome — actually interact with a variety of malignant cells in ways that contribute to their proliferation. “These findings opened an entire spectrum of new targeting agents that are making a difference in a range of patient outcomes.”

Schuller, a retired surgical oncologist who specialized in head and neck cancers and formerly led both the OSUCCC and The James, references “a never-ending list” of other individuals at Ohio State who have helped change the landscape of cancer care.

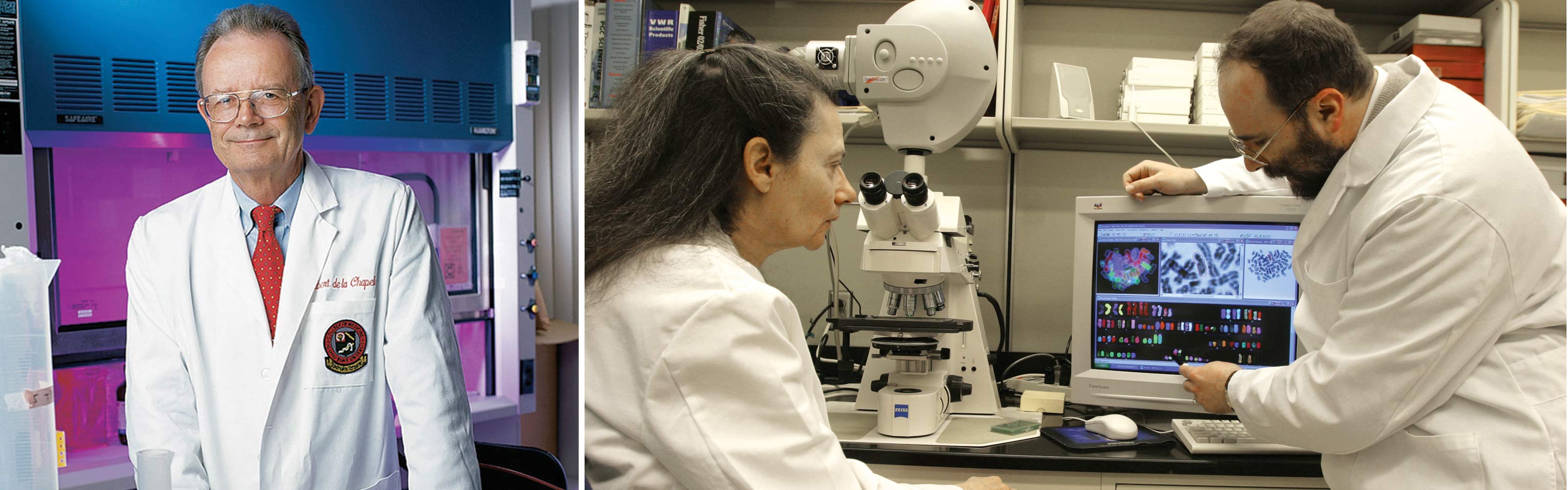

“Dr. Bertha Bouroncle several years ago not only identified a new form of leukemia, so-called hairy cell leukemia, or HCL, but then she and her colleagues, including Drs. Eric Kraut and Michael Grever, later developed a drug that was found to be highly effective and possibly curative for HCL,” Schuller says. “And the list goes on, whether it’s Dr. Albert de la Chapelle and his colleagues in their groundbreaking work in the diagnosis and prevention of certain forms of colon cancer, or Dr. Clara Bloomfield’s international leadership in classifying and predicting the level of aggressiveness of acute leukemias, or our collective work to help patients with head and neck cancers.”

Right image: Clara D. Bloomfield, MD, a former director of Ohio State’s Comprehensive Cancer Center who later became cancer scholar and senior adviser to the university’s cancer program, is shown in her research lab with colleague Krzysztof Mrozek, MD, PhD. Bloomfield was at Ohio State from 1997-2020

Pointing out that treatments for cancers of the mouth, throat and larynx can compromise important life functions such as swallowing, speaking and face aesthetics, Schuller says the head and neck program at the OSUCCC – James “has been a national leader in developing new surgical reconstruction techniques that have improved quality of life for many of these patients.”

“The research that our program did early on in treating this disease with chemotherapy and radiation led to an international study that demonstrated a more than doubling of cure rates for nasopharyngeal cancer, one of the most common malignancies in the world.”

Still another innovation has been the discovery that certain head and neck cancers are caused by a virus rather than damages wrought by tobacco and alcohol use.

“Several years ago, a researcher whom we ultimately recruited to Ohio State, Dr. Maura Gillison, identified the relationship of the human papillomavirus, or HPV, to certain cancers of the throat,” Schuller says. “She’s led an international effort that has enabled us to develop treatment programs that are less toxic and more responsive, causing dramatic improvements in treating these cancers that are linked to a virus rather than to external carcinogens.”

The James CEO points to several advances within his specialty of breast cancer over the past 50 years, such as refinements in mammography and the emergence of effective drugs for treating this malady in its various subtypes that have been identified through molecular genetics.

“Modern mammography methods were developed late in the 1960s and first officially recommended by the American Cancer Society in 1976,” says Farrar, who also served as medical director of the Stefanie Spielman Comprehensive Breast Center at the OSUCCC – James for many years. “The mammogram continues to be the most reliable way to screen for breast cancer.”

In 1978, the FDA approved tamoxifen, an anti-estrogen drug originally developed as a birth control treatment, for treating breast cancer, Farrar says, adding that tamoxifen “represents the first of a class of drugs known as selective estrogen receptor modulators, or SERMs, to be approved for cancer therapy.”

Two decades later, in 1998, the OSUCCC – James was recognized for contributing to a landmark national study called the Breast Cancer Prevention Trial that, over the previous six years, had shown a 45% reduction in breast cancer cases among women at high risk for the disease who took tamoxifen versus a placebo. Tamoxifen became the first drug known to prevent rather than just treat breast cancer.

Right image: Former Ohio First Lady Janet Voinovich cuts a ribbon at the dedication of the JamesCare Mammography Center at Macy’s Tuttle Crossing in Dublin in the late 1990s. Among those shown are Bernadine Healy, MD (second from left), then-dean of the Ohio State College of Medicine; and Clara D. Bloomfield, MD (second from right), then-director of the OSUCCC and deputy director of The James.

Among other advances Farrar mentions for treating breast cancer are:

- 1985 – An NCI-supported clinical trial showed that women with early-stage breast cancer who were treated with breast-conserving surgery (lumpectomy) followed by whole-breast radiation therapy had similar rates of overall survival and disease-free survival as women who were treated with mastectomy alone.

- 1998 – Chemotherapy before surgery helped more women benefit from breast-conserving treatment.

- 1998 – The first targeted anti-breast cancer drug, trastuzumab (Herceptin), was shown to have a major impact on breast cancer care.

- 2000s – Clinical trials helped establish new standards of care for patients with breast cancer.

A professor emeritus who for many years chaired the Department of Internal Medicine at Ohio State and co-led the former Experimental Therapeutics Program at the OSUCCC – James, Grever says many drug development accomplishments at the university have had international impact, including the identification of pentostatin as one of the first agents to secure durable (long-lasting) remissions in patients with HCL.

“Dr. Bertha Bouroncle was one of the initial investigators to describe the details of hairy cell leukemia,” Grever says, referring to a breakthrough 1958 paper in the journal Blood. “Working as a team in the 1980s, Drs. Bouroncle, Kraut and I led the development of pentostatin, an agent that changed the natural history of this disease.” In the 1990s, Grever chaired an international study that compared pentostatin to an agent called interferon for treating HCL and found that pentostatin produced significantly higher response rates of durable remission, reconfirming its efficacy.

Right image: Eric Kraut, MD, of the Division of Hematology, was a colleague of Dr. Bouroncle’s who helped devise a therapy for (HCL).

His work with HCL continued. In 2008 he convened an international meeting of experts to address unanswered questions regarding this rare disease, an effort that led to establishment of the Hairy Cell Leukemia Foundation, which is directed by patients with HCL in many countries. Grever chairs the Scientific Committee for the foundation, which supports research grants focused on the disease.

Earlier in his career, he also conducted one of the first studies of the drug fludarabine and described its use in treating CLL – a study that led to its international use as the main drug for CLL for many years before the arrival of BTK inhibitor drugs.

Grever also acknowledges the work of his longtime former colleague, John Byrd, MD, for guiding fundamental studies showing the overall potential of BTK inhibitors in the treatment of CLL.

“Dr. Byrd was a leader in leukemia research for many years at the OSUCCC – James,” Grever says.

“His efforts were extremely important for introducing targeted new therapies for CLL, and he also established important initiatives in searching for targeted therapy in acute leukemia. He was a key figure in drug development at Ohio State.”

Grever says innovative work in hematologic malignancies has continued at the OSUCCC – James through the efforts of talented scientists such as Jennifer Woyach, MD, who co-leads the Leukemia Research Program with Ramiro Garzon, MD. “Dr. Woyach has become a leading expert in CLL; she defined the mechanism of resistance to BTK inhibitors such as ibrutinib in treatment failure for some patients with this disease,” Grever says. “And Dr. Kerry Rogers published the successful results of using ibrutinib to treat patients with refractory or relapsed HCL.

One of the nation’s top researchers in population science, Paskett, who serves as associate director for population science and community outreach at the OSUCCC – James, has often said that she and her colleagues have no conventional laboratory. “The community is our laboratory,” she explains.

Among her top choices for global cancer advances of the past 50 years are a vaccine for HPV (a virus that can cause several types of cancer); improved screening for breast, lung, colorectal and cervical cancer; adjuvant anti-estrogen therapy for women with breast cancer; and the emergence of immunotherapy. But she also acknowledges important gains that have been made within her own discipline.

Since Paskett arrived in 2002 as co-leader of the Cancer Control Program and founding director of the Center for Cancer Health Equity at the OSUCCC – James, she and her research colleagues have made major contributions to improving public health and health care by designing interventions that help people prevent or reduce the cancer burden. Her team’s focus has been on racial/ethnic-minority and underserved populations in rural/Appalachian areas of Ohio and bordering states.

While at Ohio State, Paskett has obtained more than $76.5 million in grant funding, including an NCI-funded Center for Population Health and Health Disparities grant to examine why rates of cervical cancer are high in Appalachian Ohio. She has also received an NCI grant to increase screening rates for breast, cervical and colorectal cancer among women in rural Ohio and Indiana, a population that underutilizes these screening tests. And she leads a multi-university team in an NCI grant to implement a cervical cancer prevention program in over 30 clinics within four Appalachian regions.

Asked about major advances in cancer care at Ohio State that stem from her team’s work, Paskett mentions their involvement in a study that validated “patient navigation” – defined as patient-centered interventions that provide access to diagnosis and treatment by removing obstacles to care – as a means of saving lives among underserved individuals.

“We are also part of the Women’s Health Initiative national study that demonstrated that estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women can cause breast cancer,” Paskett says.“Reducing that intake as a result of this study has also saved lives.”

She and her colleagues view population science and cancer survivorship as vital aspects of the health care continuum – disciplines that encompass life-saving research without vials, tubes and beakers.

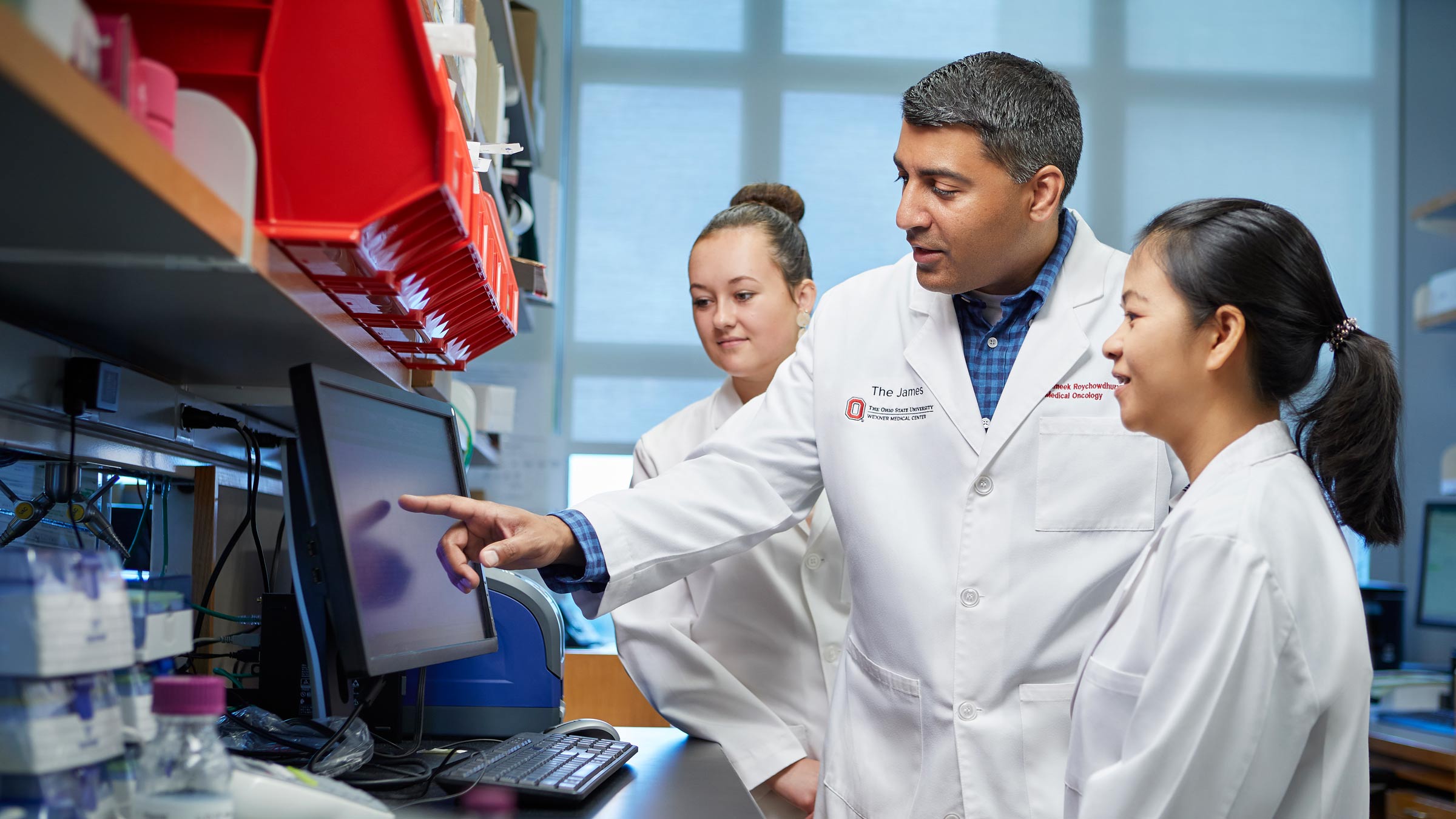

Along with technologies that have arisen in the past decade to characterize the human genome, Roychowdhury ranks the emergence of immunotherapy among the top advances in cancer care.

“For decades, immunologists have tried to harness the immune system to reject and treat cancer. In the 1990s a molecule called interleukin-2 proved to be highly effective in 5-8% of patients with advanced kidney cancer or melanoma,” he says. “But this therapy was like stepping on the gas pedal of the immune system, and as a result it proved to be very toxic, and not all patients could withstand it.

“Fortunately around 2010,” he adds, “novel immune-based therapies were developed that would instead ‘cut the brakes’ on the immune system, making them less toxic, and these are now highly effective against and approved for 16 different cancers. This has helped bring new investment of resources for research on the immune system’s potential.”

Roychowdhury’s NCI-funded precision oncology lab team evaluates patients with advanced late-stage cancer; develops diagnostics, tools and methods to analyze and interpret genomics data; and devises therapies for testing in clinical trials. He helped launch the field of precision cancer medicine through the first clinical trial to use genomic sequencing in patient care for cancer – a study that was published in the journal Science Translational Medicine in 2011. Since 2012, his team has been developing clinical trials focused on genomic alterations and matching patients to personalized therapies.

One major success story has been the identification of the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) gene alterations in cancer, which Roychowdhury helped discover in 2011. “Alterations in these genes can occur across multiple cancer types,” he says. “Our team has worked to develop special diagnostic tests to detect FGFR gene mutations, and we have participated in several clinical trials for matching patients to FGFR-targeted therapies. This work helped lead to the May 2021 approval of an oral FGFR drug called infigratinib for treating patients who have liver cancer and FGFR gene mutations.”

A recent example of how precision cancer medicine and immunotherapy can be combined, he says, is the discovery of a gene marker known as MSI-H.

“This genetic marker can be found in any cancer type and renders patients’ tumors very sensitive to immunotherapy,” he explains.“Even patients with advanced cancers can be cured if they have this genetic marker. Ohio State contributed to a clinical trial for pembrolizumab immunotherapy, which helped get this therapy approved by the FDA in May 2017 for any kind of cancer. This was the first drug approved for a genetic target that is agnostic to any tumor type.”

Ramaswamy, a medical oncologist specializing in breast cancer, says breast cancer in the past 50 years “has gone from a single disease to multiple distinct subtypes.”

She can name several worldwide advances in her discipline over the past half century, including: molecular subtyping of breast cancers and discovery of the HER2 oncogene; clinically validated genomic tests that help clinicians better understand tumor biology and select appropriate therapies; and the addition of multiple targeted agents that have improved cure rates.

“The key biomarkers for each breast cancer subtype are tested through clinically validated methods on every new patient with cancer,” she says, “and this dictates the management of our patients with the use of targeted therapies that have improved clinical outcomes.”

Ramaswamy focuses her research on the biology of breast cancer to identify characteristics of tumors that are resistant to hormone-based therapeutics so that scientists can develop alternative therapies for those malignancies.

“We’ve identified biomarkers of resistance to anti-estrogen therapies and to endocrine therapies,” she says.

“We’ve conducted novel therapeutic trials for patients with triple-negative breast cancers who are at risk for rapid relapse.” Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is an aggressive breast cancer not sustained by the estrogen or progesterone hormones, or by the HER2 protein, making it difficult to target for treatment.

“Our researchers have also identified the biological link between lack of breastfeeding and risk of TNBC,” she adds. “This data will help us develop strategies for preventing TNBC and can also impact racial disparities in breast cancer outcomes.”

Read more stories from the 50 years of cancer series:

Your support fuels our vision to create a cancer-free world

Your support of cancer care and pioneering research at Ohio State can make a difference in the lives of today’s patients while supporting our work to improve treatment and reduce cases tomorrow.

Ways to Give