The heart disease puzzle: Why don’t all patients fare the same?

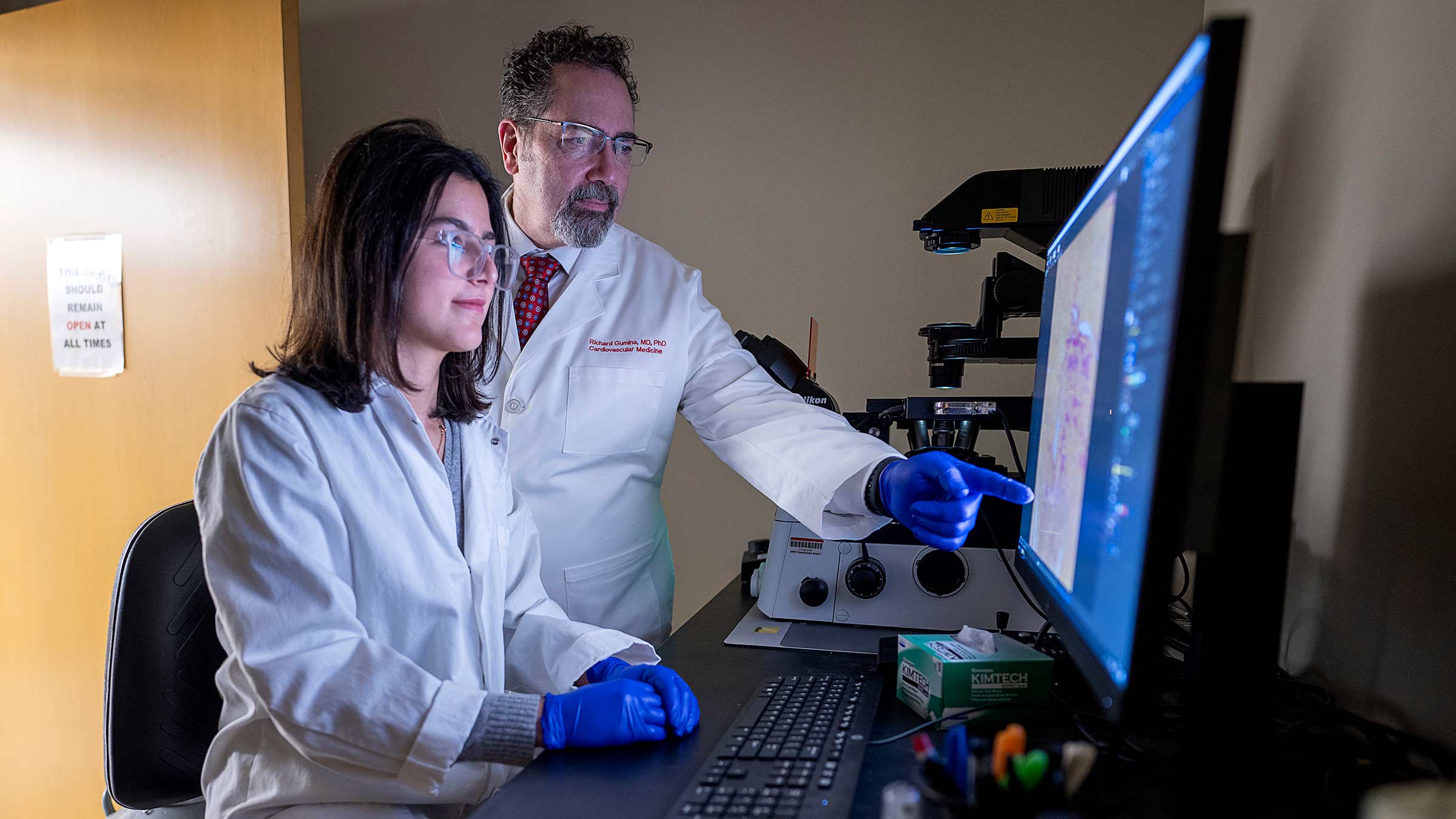

Interventional cardiologist Richard Gumina, MD, PhD, splits time between the bedside and the research lab to improve the odds against the No. 1 killer.

For Richard Gumina, MD, PhD, the most satisfying part of treating heart disease is watching patients who are among the sickest of the sick turn around quickly.

Dr. Gumina has spent his career as an interventional cardiologist, performing procedures to open blocked arteries and restore blood flow to the heart.

Improvement can happen within minutes.

But Dr. Gumina doesn’t sugarcoat things. He’s quick to add that there’s a yin and a yang to what he does. Not all patients respond well.

That’s why Dr. Gumina splits his time at the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center between patient care and his research lab, where he searches for answers to reduce risk to those most vulnerable to heart disease, which ranks as the top cause of death in the United States.

As director of the Division of Cardiovascular Medicine at the Ohio State University College of Medicine, Dr. Gumina also encourages outside-the-box thinking among his colleagues, seeking to further the understanding of disease and develop new drugs, therapies and treatment approaches.

He also intends to elevate the way care is provided.

“My goal is to transform how we provide care, not only locally, but to the greater Ohio community, and to make sure that we’re always patient-centric, that we’re taking care of each patient the way we would like our parents to be taken care of,” Dr. Gumina says.

Finding genetic clues to heart attack recovery

Over the years as Dr. Gumina treated heart disease, he became curious as to why all patients who appeared to have similar heart attacks didn’t fare the same. They received the same types of treatments and the same medications. But some responded well while some didn’t.

Was there something else going on? He wanted to find out, so he took the question to his lab.

Because there are many immune-related conditions, such as lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, that affect the heart, he started looking at immunology and inflammation. His question: How does inflammation impact how the heart heals?

Dr. Gumina’s research focuses specifically on how inflammation contributes to coronary artery disease — the condition in which fatty deposits build up in the major blood vessels that supply blood to the heart.

“We think we’ve identified genetic differences that each of us have that will tell us who’s going to do better and who’s going to do worse after a heart attack,” Dr. Gumina says.

This could help update and personalize treatment approaches.

“We’ll be able to look at whether we need to change therapies to prevent another heart attack or heart failure,” Dr. Gumina explains. “The other thing to look at is how we develop targeted therapies, based on these genetics, to impact how patients respond after a heart attack.”

Dr. Gumina says this type of change is why he chose to work at an institution like the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, where physician-scientists at the Heart and Vascular Center collaborate with experts in various colleges, all within walking distance, to find answers to complex questions that benefit patients.

“We want to be able to understand patient risks and drive the next line of therapies to advance care and improve patient outcomes and survival,” he says. “We have as an academic institution the ability to ask complex questions and to come up with new therapies that can affect patients’ lives.”

Paying it forward in the lab

Cardiologist Michael Wesley Milks, MD, worked alongside Dr. Gumina in 2008-2009 as a medical student in the lab, where he says he was inspired by the integrity, oversight and scrutiny of the scientific process.

As a mentor, Dr. Gumina connects with people on a personal level, says Dr. Milks, now a clinical associate professor of Internal Medicine at the Ohio State College of Medicine.

“He’s a good facilitator of the passion that is growing within you; he has a way of seeing it, recognizing it and then doing what he can to nurture it,” Dr. Milks says.

Dr. Gumina says he had several great mentors of his own, including a mentor who introduced him to cardiovascular research at a high level. Paying it forward has been a point of pride.

Now Dr. Gumina’s colleague at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center Richard M. Ross Heart Hospital, Dr. Milks says his mentor is viewed not only as a powerhouse in the research arena, but also someone who is always available for patients and colleagues.

“Over my career, I’ve had more than 50 undergraduates or graduate students come through the lab,” he says. “It’s great to see people who have trained with you go on to do things way bigger and better than you could even dream for yourself.”

“We’re lucky to have him as a leader,” Dr. Milks says. “He does scientific research at a high and impactful level. However, he is also a gifted clinician, the kind of person that really is very diligent with patient care. He is compassionate and known for his devotion to treating the patient, consistently putting in the time and the effort.”

Setting a good example of cardiac care

Dr. Gumina is Suani Nkozi’s favorite cardiologist.

“He’s my only cardiologist, but he’s my favorite,” Nkozi says with a laugh.

“I don’t know how the other cardiologists are in their practice and their bedside manner, but if he is the example, he’s done a fantastic job,” he explains. “He and I clicked almost immediately. We talk, we joke, we laugh, he’s patient with me, we engage, and he’s convinced me and has made me feel like he likes me as a person.”

Dr. Gumina also convinced Nkozi to take his blood-thinning medication.

Nkozi was reluctant after his heart attack in 2020 because he doesn’t like being on medicines and has avoided taking drugs his whole life. He’d believed that after a year, he could stop using the blood-thinning medicine.

But Dr. Gumina drew a picture, showing Nkozi where a small mesh stent tube had been placed to open a main artery that supplies blood and oxygen to his heart.

“That main artery, if completely closed, we call that the widow-maker,” he told Nkozi, “and that was 80%-85% closed.”

“And after that, it was quiet, and it felt really somber in that room. I didn’t know what else to say,” recalls Nkozi, who was 48 at the time. “I didn’t realize that I was that close to death. I saw in that moment what would have taken me out and I didn’t even know. So, after that, I stopped asking him about removing the blood-thinning medication from my daily pill regimen, because he was saying I needed it.”

Nkozi had ended up in an emergency department close to his Pickerington home after chest pain made him cut short a walk with his wife. He chalked it up to a recent workout and eventually went to lie down. When he started feeling nauseated, his wife insisted they make the trip to the ED.

After a few tests, Nkozi was in an ambulance on the way to the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center. At the hospital, he was told he was having a heart attack, and an interventional cardiologist ran a catheter up his arm into his chest to release dye in the vessels to find the source of the blockage. After it was discovered, the stent was placed to open the artery.

Nkozi was shocked. He doesn’t drink or use tobacco or drugs. He has manageable cholesterol levels. The only medication he was taking was the lowest dosage of a blood pressure pill, and he was working to lose a few pounds so he could stop taking it.

Turns out, he has an irregular-sized artery. One that could have killed him if his wife hadn’t pressed him to go to the ED.

His follow-up care with Dr. Gumina is something both Nkozi and his wife look forward to.

“I love Dr. Gumina to pieces, so it’s an opportunity for us to catch up,” says Nkozi’s wife, Shandalai Nkozi. “Dr. Gumina’s been great.”

Connecting with patients like family

Growing up in a close family, Dr. Gumina says his relationship with his patients is a reflection of how he feels about family.

“It’s important that I can explain things to my mom the same way I can explain things to my patients,” Dr. Gumina says.

“It’s important to make it real and not talk the science-talk, but to understand that it’s important for patients to connect with you and make sure that they know that you’ve come from not dissimilar places, and that you know you’re there to help them.”

He says he’s continually learning from his patients, and one of the biggest lessons has been humility.

“It’s a privilege to care for people and to be brought into their lives and see them at very vulnerable times, sometimes, and to have the respect for them and their individual wishes,” Dr. Gumina says. “That is an important aspect of what we do. Patients need to know that you have empathy for what they’re dealing with.”

Your heart is in the right place

Learn more about advances in care and treatment for patients at The Ohio State University Heart and Vascular Center.

Expert care starts here