With thousands awaiting organ transplants, Ohio State surgeon is expanding organ availability to save more lives

Kenneth Washburn, MD, was recruited to transform Ohio State’s transplant program, and he’s not done yet, with a focus on expanding living organ donation.

Kenneth Washburn, MD, never expected to be in the operating room performing a transplant on the renowned surgeon who hired him.

Steven Steinberg, MD, a trauma surgeon, was the interim chair of the Department of Surgery in 2016 when he helped recruit Dr. Washburn to Ohio State from the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

But in summer 2021, not long after he had retired from Ohio State, Dr. Steinberg’s health suddenly deteriorated. He was diagnosed with a liver condition of an undetermined cause.

“One night I got a call, he was here in the hospital. His wife, who is a nurse here, knew all the bad stuff that could happen. He was deathly ill,” Dr. Washburn remembers.

One thing was clear: Dr. Steinberg needed a liver transplant to save his life.

Dr. Steinberg spent a career gowned, gloved and operating under bright surgical lights. Now he was the one who would be on the operating table.

“It’s easy for a surgeon to see that another surgeon is really technically gifted. I also could easily imagine that my operation was going to require that,” Dr. Steinberg says.

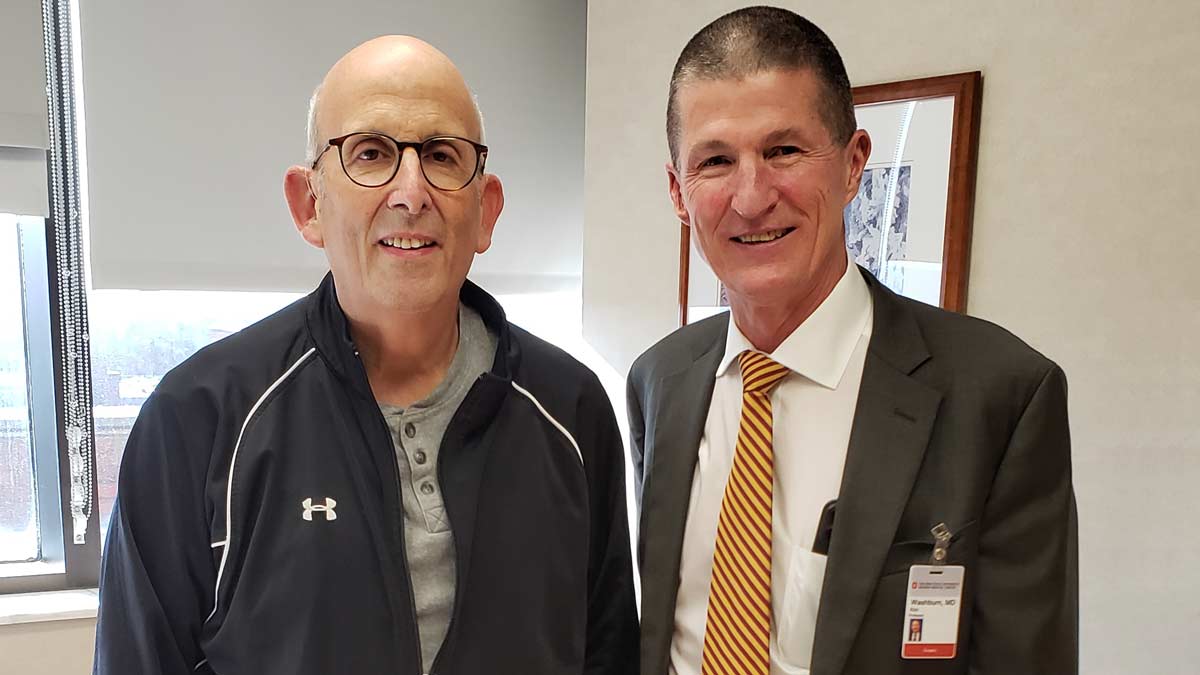

Steven Steinberg, MD (left) meets with Kenneth Washburn, MD during a clinic visit after his liver transplant.

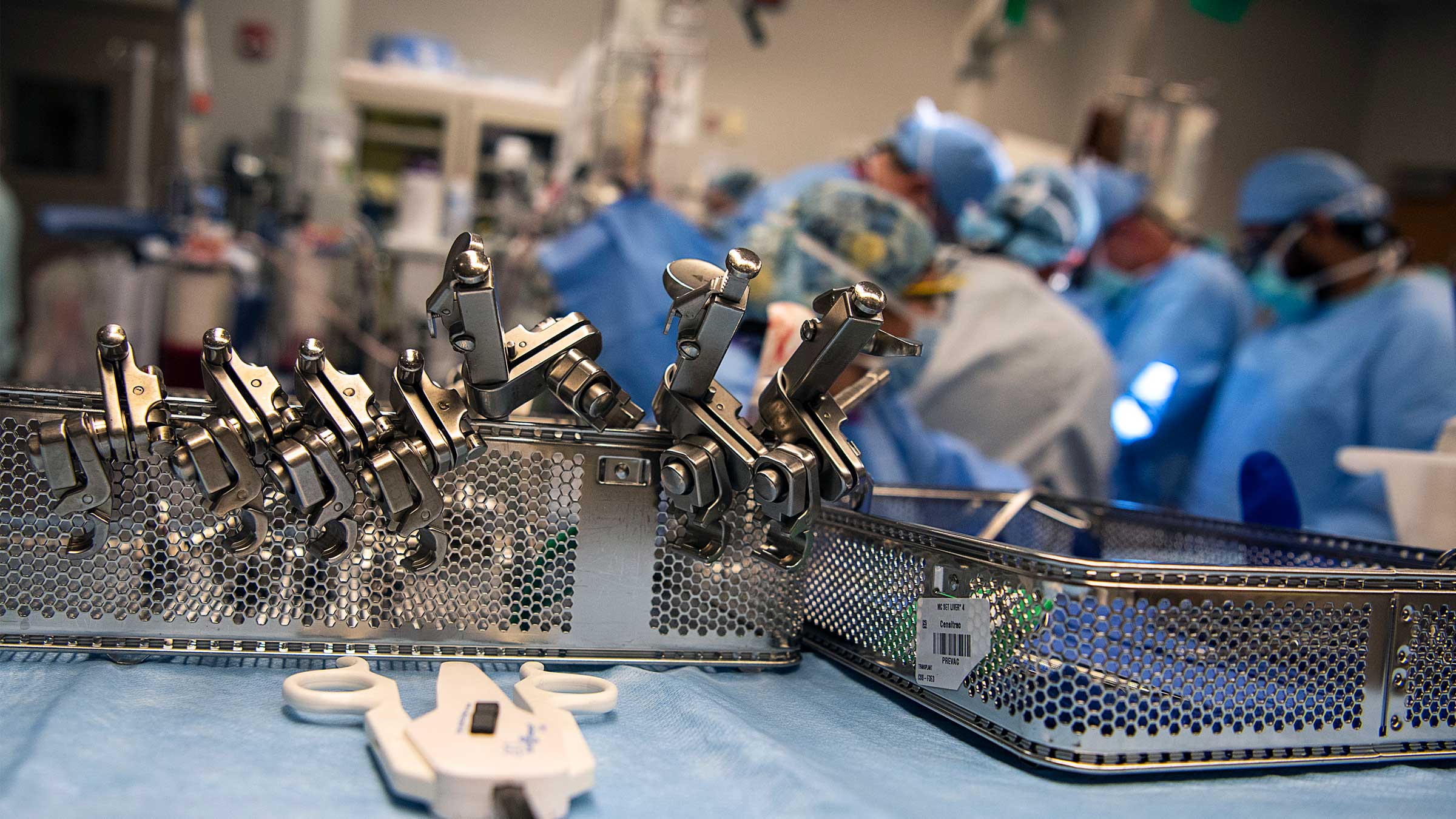

Liver transplants are often four-to-six-hour operations that require careful orchestration of a team of surgeons, anesthesiologists, surgical techs and nurses to successfully execute the procedure. There’s often little notice of when transplant surgeries will occur because it’s unknown when a matched organ will become available.

While the surgery is life-changing for the recipient, they’re commonplace for specialists like Dr. Washburn, who’s the executive director of the Comprehensive Transplant Center (CTC) at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center and director of the Division of Transplantation Surgery in the Ohio State College of Medicine. He specializes in abdominal transplant surgeries for kidney and liver. He’s also a strong advocate for living kidney and living liver donations.

“I’ve done this for almost 30 years. You see people who are back to a functional life and doing stuff with their kids, their grandkids. They are going to go back to work,” Dr. Washburn says. “That, I think, is what really keeps me doing this.”

In his time at Ohio State, Dr. Washburn has transformed the transplant program into one of the highest-volume programs in the nation with impressive outcomes for its patients. That means more people in need of organs are getting transplants.

In 2021, the transplant center ranked as the seventh-busiest transplant program in the nation, with 601 transplants — a 74% increase since Dr. Washburn arrived.

Download a report of Ohio State’s most recent transplant patient outcomes

A path to transplant surgery

Dr. Washburn grew up in the Boston area in a middle-class family, the oldest of three brothers.

“My dad was an engineer, and my mom was a homemaker. So, we had what we needed, but we still took loans out to go to college.”

He received a master’s degree in chemistry from Penn State University and started looking at medical schools. He would go on to attend the University of Pittsburgh Medical School.

“I ended up taking loans out the first year. I can’t remember how much, but it was a lot of money,” he says. “I was thinking, ‘It’s all on me.’”

Dr. Washburn knew classmates who had military scholarships.

“The military scholarships are pretty competitive to get and you certainly have to be worthy, comply and follow the rules,” he says, recalling his decision to talk to an Air Force recruiter.

“I applied, and I was fortunate to get one. I spent every summer, for three years, six weeks at a time, with the Air Force going somewhere. They paid for everything, which was great,” Dr. Washburn says. “So I essentially had no loans after that first year. That was incredibly fortuitous in many fashions, not just financially.”

During Dr. Washburn’s second year of medical school, his spleen ruptured from a skiing accident. He was taken to a hospital to undergo an emergency splenectomy, where his spleen was removed.

“I think it was one of the pivotal moments for me. I’d just had major surgery, and these guys saved my life. I was literally bleeding to death,” Dr. Washburn says. “I think that played a role as I got into my third year of clinical medicine.”

Dr. Washburn’s personality also steered him into being a surgeon. His military background shaped him into a disciplined doctor who values precision and regimented routines. He still wears a military-style, shortly cropped haircut and laces up for his early morning regimen of a long run each day. It’s not uncommon for him to work long hours at odd times and to sleep on a gray sofa in the corner of his office.

“I think with many things that we decide to do in life, our personality has an influence on where we gravitate,” he says.

Dr. Washburn doesn’t consider himself to be an intellectual, but he always excelled at staying calm under pressure and making the definitive decisions needed in an operating room.

“If you get paralyzed by what’s in front of you, you’re not helping that patient. You may usually make the right decision, but not always. If you make a wrong decision, then you have to be willing to admit it and pivot and do something different. But we can’t be paralyzed,” he says.

He pursued fellowship training in transplant surgery that led to his current specialty.

Well before Dr. Washburn began working at the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, he first worked in San Antonio at an Air Force teaching hospital for three years to pay back the military for medical school.

In 1999, he began as a transplant surgeon at the University of Texas Health Science Center.

“I was not in charge of everything. I was given a lot of autonomy and I oversaw their liver transplant program, but I felt like I had a lot more to give,” Dr. Washburn says.

Dr. Washburn makes a move, and some big changes

Before Dr. Washburn’s arrival at Ohio State in March 2016, the number of patients being transplanted were flat.

“We were kind of stuck with low volume. Despite multiple discussions with liver leadership at the time, they didn’t foresee any possibility of growth,” says Dr. Steinberg, who spent decades at Ohio State as a surgeon specializing in critical care and trauma surgery. He served as the director of the College of Medicine’s Division of Trauma, Critical Care and Burn before holding the role of executive vice chair in the Department of Surgery.

The director of the Comprehensive Transplant Center eventually left Ohio State, leaving an important position open. It took two and half years to recruit Dr. Washburn, but Dr. Steinberg finally got his new leader.

Dr. Washburn had a proven track record of good results, was an excellent surgeon and managed a high volume of transplants, Dr. Steinberg says.

Rebuilding Ohio State’s transplant program

The Ohio State Wexner Medical Center began performing transplants in 1967, when hospitals across the country started saving lives through this innovative treatment option.

“The first transplant performed in the United States occurred in 1954, but it wasn’t until the late 1960s that liver, heart and pancreas transplants were being performed successfully. So, the art of transplantation is still fairly young,” says Laura Stillion, MHA, the administrative director of the Comprehensive Transplant Center (CTC). She’s led the transplant program at Ohio State since 2004.

“The transplant program is a vital program for Ohio State. We’re the only adult transplant program in central Ohio and one of only three locations in Ohio capable of transplanting all solid organs,” she says.

During her tenure, Stillion has watched the program transform under the guidance of four CTC executive directors, including Dr. Washburn. In the mid-2000s the abdominal programs, which include kidney, pancreas and liver, started steadily growing.

In 2008 there was a major shift for transplant programs across the country when the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services issued new regulatory Conditions of Participation that established both volume and outcome program requirements. With the revised requirements in place, Ohio State made it a priority to expand the transplant program.

When Dr. Washburn joined Ohio State, he had a vision of increasing the volume of transplants, which meant more lives would be saved, but it also meant the structure of the program had to change in order to accommodate the growth.

“When he got here, his energy was contagious and everyone was motivated to do whatever it took to save more lives,” Stillion says.

It meant making sure that medical personnel, such as nurse practitioners, were working to the maximum level of their specialty. Doing this allowed surgeons to focus on performing more transplants. A plan to recruit talented surgeons to support the growing caseloads was also skillfully implemented.

Dr. Washburn also understands the importance of training the next generation of transplant surgeons.

“I’ve done a ton of liver transplants. But it’s intentional for me to not be putting in all the stitches. I can do it, and at times, I do. It’s intentional for me to let other people do that, because then they develop their confidence under my tutelage. Then they become skillful,” he says. “To me, it’s really empowering to be able to do that and see people grow. Because then it allows us to really build out a much bigger bench of strength and capabilities. It allows us to scale things up and do more transplants.”

Austin Schenk, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of Surgery in the College of Medicine and a transplant surgeon, says Dr. Washburn has a reputation for staying calm and composed even in challenging situations. He leads by example.

“At this stage of his career, I think the real mark of success is his ability to teach in those situations,” says Dr. Schenk. “So not only can he do it himself, but he has handed that knowledge off to a whole group of the faculty here. I continue to learn things from him every time I operate with him.”

In 2021, the transplant center marked a new milestone with 1,500 liver transplants, 600 heart transplants, 500 lung transplants and 7,800 kidney transplants since the center’s inception 55 years ago.

“When I got here, we created that vision and started executing some of those things,” Dr. Washburn says. “We’re not done yet, but we’ve had tremendous success collectively as a team. It’s not me, it’s us.”

Turning his attention to expanding living organ donation

The largest source of donor organs come from deceased patients who experience brain death. One deceased patient can save up to eight people through organ donation, and heal up to 75 more through tissue donation.

More than 105,000 people in the United States are in need of an organ transplant. That total includes nearly 3,000 Ohioans, according to Lifeline of Ohio, a nonprofit organization that advocates for organ donation.

Nationally, about 20 people die every day waiting for a transplant.

There wouldn’t be a shortage of organs if there were more living donors who considered giving a kidney or a section of their liver to those in need.

Those who need kidneys are usually on dialysis, which means they have to visit a dialysis unit for five hours a day about three times a week so a machine can filter their blood.

“It’s life-altering. It’s not painful, but to take five hours out of your day three times a week, you don’t realize how big a chunk it is,” Dr. Steinberg says.

After he underwent a liver transplant, one of the immunosuppressives he was prescribed to keep his body from rejecting the liver caused kidney failure. Dr. Steinberg was on dialysis for more than two months before he returned to Ohio State for a kidney transplant.

“We know that patients have a higher risk of dying while on dialysis than they do with a kidney transplant. Collectively as a society, we’re trying to get more patients off dialysis so they have better longevity,” Dr. Washburn says. “Living donation is a great way to do that quickly. It’s not an option for everybody, but we’re in a process of really trying to educate people.”

The goal of Ohio State’s transplant program is simple — help as many people as possible. A concerted effort was made to build the infrastructure and hire the surgical expertise to establish a living donor program at Ohio State, something not all transplant centers have.

“Everyone is a transplant candidate until proven otherwise,” Dr. Schenk says. “So when you evaluate patients, the starting position is, ‘Yes, we can help you. Yes, a transplant will help you.’”

The future of organ transplantation at Ohio State

Over the last six years, Dr. Washburn has prioritized the growth of the transplant program’s Organ Assessment and Repair Center. Here, surgeon-scientists and the organ recovery team utilize organ perfusion to rehabilitate donated organs that would otherwise be unusable.

“The benefit of having an in-house Organ Assessment and Repair Center is twofold,” Dr. Washburn says. “We not only have the ability to assess the health of organs prior to transplantation, but now have the ability to repair some organs that previously would have been discarded. So we are not only able to transplant healthier organs, but also transplant more organs — which ultimately translates to better outcomes for our patients and saving more lives.”

Historically, donated organs were placed on ice without blood flow until transplanted. Now with organ perfusion, this newer technology pumps warm blood through the organ within a sterile container, while measuring other vital statistics and helping to revitalize and, at times, repair it.

The transplant center has perfused kidneys for years, started performing ex-vivo lung perfusion in 2016, and added TransMedics heart perfusion, also called “heart in a box,” in 2021.

OrganOx liver perfusion machine can preserve donor livers for up to 24 hours, allowing it to travel farther to the sickest patient in need. The transplant team recently tested a donor liver on the machine.

Prior to being placed on the perfusion pump, the liver was gray and to the untrained eye, didn’t appear to be a healthy, viable organ. But once the perfusion solution was connected, within minutes, the liver returned to a healthy shade of bright red once again.

In addition to organ perfusion, Dr. Washburn is supportive of his team’s research involving immune suppression that goes hand in hand with organ transplant.

Dr. Schenk is working on developing cellular therapy for transplant patients to help reduce the need for immune suppression medicine.

“He’s been extremely supportive of my laboratory. My job description is 50% research and 50% surgery. He hired me to build a successful lab and he’s helping me do it,” Dr. Schenk says.

If successful, it would mean transplant patients would no longer have to take drugs that have severe side effects. The drugs are necessary to prevent organ rejection but can lead to cancer, diabetes and reduced kidney function.

“That’s the downside of transplant. If we could replace those noxious medications that prevent rejection, without all the bad side effects, that would be amazing,” Dr. Schenk says.

A surgeon’s surgeon

As for Dr. Steinberg, after a year of two major abdominal surgeries, he feels much better.

“It was a tough year,” he says. “Liver disease sneaks up on you to the point where you may not even realize how badly you feel until after you get a new liver. So prior to the liver transplant, I had no energy. I had a large amount of swelling. It was like 40 or 50 pounds of water.”

Dr. Steinberg remembers that it wasn’t painful but recalls he never felt good.

“That changed immediately after recovery from a liver transplant,” he says. “I got rid of a lot of fluid. My weight just before surgery was 220 pounds, give or take. Now I’m 165 pounds.”

“I couldn’t ask for a better surgeon,” Dr. Steinberg says.

Hiring Dr. Washburn for the transplant program was a pivotal move for the medical center, but a move that would ultimately affect Dr. Steinberg on such a personal level.

“I and thousands of people owe him our lives,” Dr. Steinberg says.

“Watching the changes in the transplant program has been one of the real pleasures of my career,” he says. “It’s finally become what I thought it could be.”

The best option for a patient waiting for a kidney transplant is to receive one from a living donor.

Explore living kidney donation