Skull reconstruction restores ‘normal life’ to patients after head traumas

Patients travel from afar for the life-restoring cranioplasty skills of Kerry-Ann Mitchell, MD, PhD, one of the few surgeons in the field of neuroplastic surgery.

Silver strands of hair fall to the floor in a pile as Kerry-Ann Mitchell, MD, PhD, moves the clippers across Vicki Rich’s head.

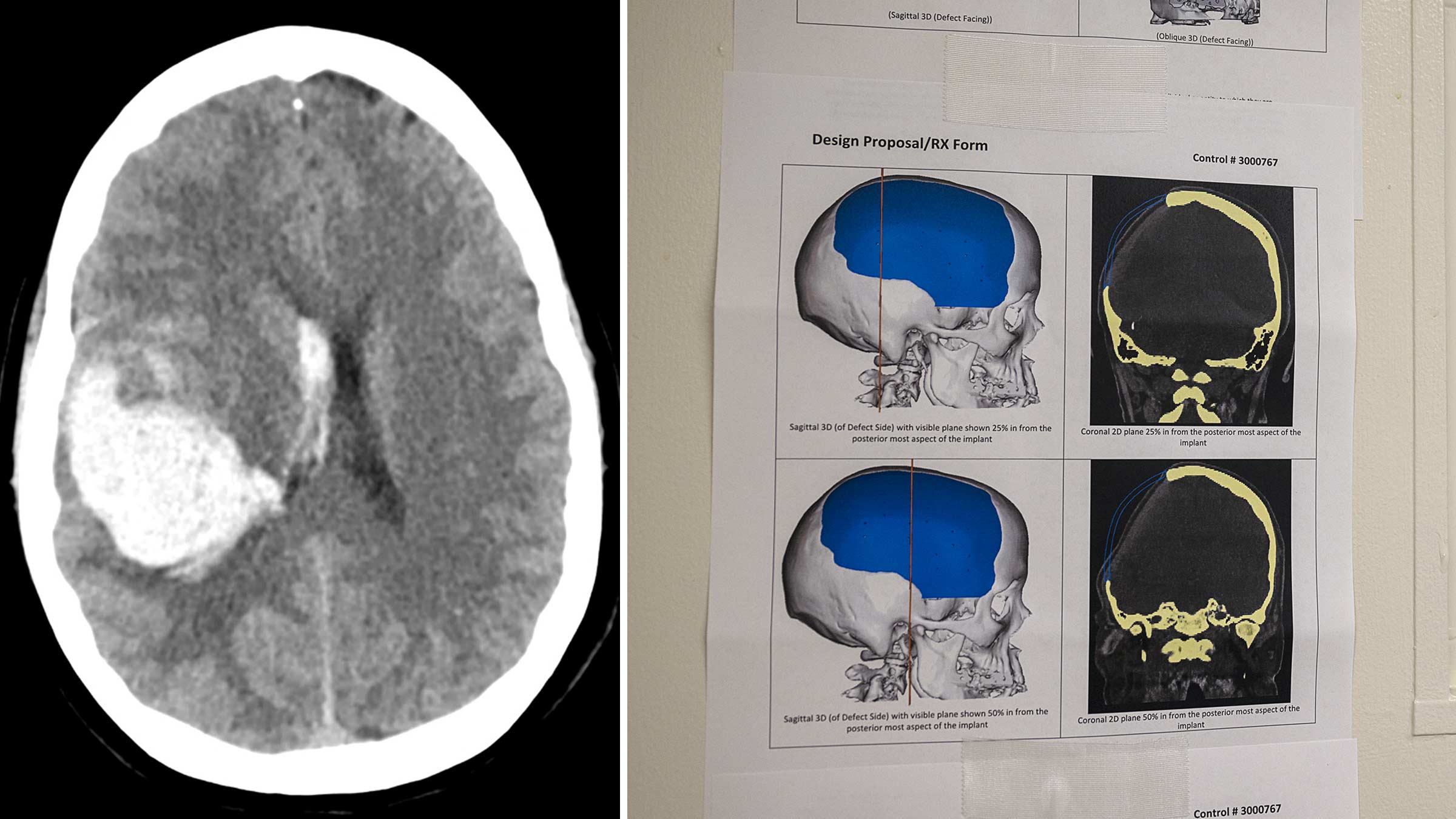

Emergency stroke treatment saved Vicki’s life but left her without the right side of her skull, creating an unsightly and painful indentation on the side of her head.

Dr. Mitchell, one of the few neuroplastic surgeons in the United States, specializes in rebuilding the delicate anatomy of damaged skulls like Vicki’s.

She makes an incision along the skull allowing her to insert a precisely shaped clear, synthetic implant to fit the space of the missing bone.

“I use a lot of synthetic materials simply because the bone isn’t available by the time patients are referred to me. They’re long past where their bone has been infected and discarded,” says Dr. Mitchell, assistant professor of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at The Ohio State University College of Medicine.

Once the implant is in place, Dr. Mitchell weaves careful, meticulous sutures along Vicki’s scalp.

This surgery, known as a cranioplasty, corrects the shape of the skull and lasts between two to four hours.

The effects are life-changing for patients.

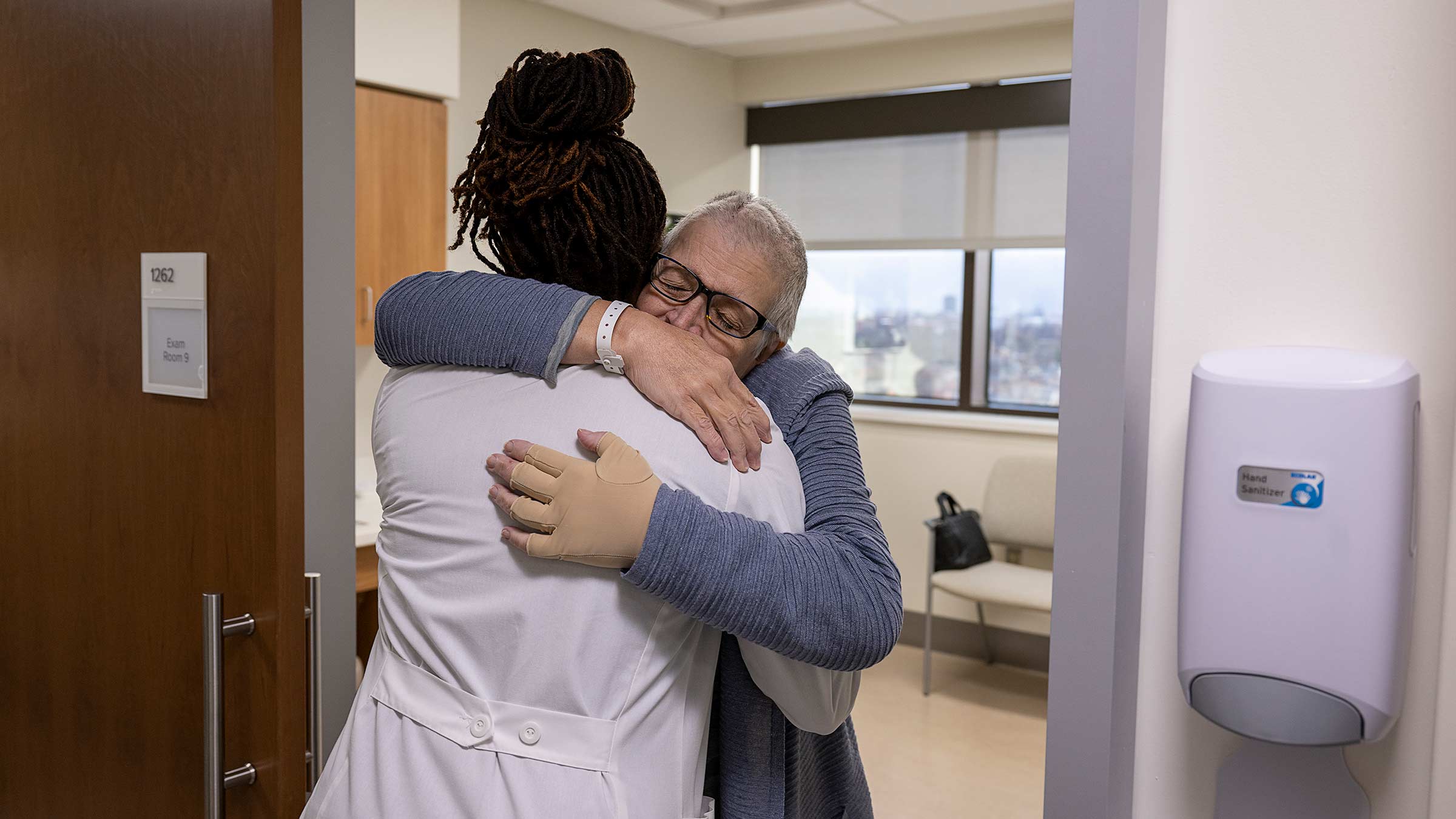

During an office appointment that follows her November surgery, Vicki is on the verge of crying as she throws her arms around Dr. Mitchell.

“Thank God for bringing you into my life,” Vicki says.

Filling a growing need for patients suffering neuro traumas

The specialty of neuroplastic surgery marries neurosurgery with plastic surgery to restore the appearance and function of patients who have survived invasive operations and treatments from conditions including brain cancer, traumatic brain injuries or strokes.

"There’s only five neuroplastic programs in the entire country, and only three of those treat civilian populations,” Dr. Mitchell says. “We have developed expertise for particularly complex patients.”

These surgeries help patients get back to normal, restore their dignity and improve their self-esteem.

“Plastic surgeons are the quarterbacks of care for many patients with complex surgical problems,” says Amy Moore, MD, the Robert L. Ruberg MD Alumni Chair of the Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery.

“We work alongside other surgical teams to provide innovative strategies for improved outcomes for patients,” says Dr. Moore.

Neuroplastic surgeons hone their skills completing skull and microvascular reconstructions and scalp grafts.

“Together with the neurosurgeons, we’re able to provide specialized care for patients with complex neurosurgical needs. We allow the neurosurgeons to do their expert work while we take care of the skull’s bony framework and soft tissue. Everyone wins here — the patients and the surgeons,” Dr. Moore says.

Finding a calling in neuroplastic surgery

Nearly 24 years ago, Dr. Mitchell came to the United States from Jamaica with $300 in her pocket.

“I was 17 years old on an academic scholarship in a new country where I knew no one,” she says.

She worked her way through school earning both a medical degree from Stanford University and a PhD in neuroscience from the University of Utah.

“I vividly remember the case that made me want to become a plastic surgeon,” she says.

Cancer that covered the face of an elderly patient had left him disfigured.

She remembers looking at the patient and asking the reconstructive plastic surgeon, “Why are we doing this major, high-risk operation instead of allowing him to go home and be with his family during this time?”

“He told me, ‘Because not only can this patient go home and be with his family, but he can also have a face. Even if he only has six months or a year to live, he probably wants to have a face while he’s alive,’” she recalls.

That’s when it clicked.

“That’s what I want to do,” she says. “Regardless of a patient’s disease or diagnosis, I want to help make their quality of life better.”

She went on to complete a neuroplastic surgery fellowship at Johns Hopkins University.

It was nearly four years ago that Dr. Mitchell interviewed for a plastic surgery position at Ohio State.

Dr. Moore calls it fate.

“We started talking about her research, and I could see her passion. I asked her, ‘OK, would you want to build that here?’” Dr. Moore says.

Now the neuroplastic surgery program is expanding, including the addition of another surgeon.

“It’s very gratifying,” Dr. Mitchell says. “You get to help patients move on after they’ve had their tumors or their trauma. I’ve come full circle.”

Why patients go without reconstructive surgery

Cranioplasties in general are risky procedures where one in three surgeries fail.

Dr. Mitchell has a better success rate.

“In our hands, looking back on our data since we established the program at Ohio State, it’s less than 1 in 10 where we have to re-operate on a patient,” she says.

Patients from all over the United States and world with complex skull deformities, and often multiple previous cranioplasty attempts, are referred to Ohio State.

Some of Dr. Mitchell’s patients come to her having gone years without skull reconstruction surgery.

The reason?

“Unless you have a specialist like Dr. Mitchell who can do what she can do, you start getting into a greater risk of worse outcomes for the patient,” says Patrick Youssef, MD, a vascular neurosurgeon and assistant professor of Neurological Surgery. “She uses not just the basics of surgical techniques, but the intricacies of plastic surgical techniques to allow us to continue on from where we would previously stop.”

Dr. Mitchell hopes these types of skull reconstructions become an expected standard of care as the specialty grows, similar to breast reconstruction.

“Women who get mastectomies for breast cancer are able to return to their normal quality of life after reconstructive surgery,” she says. “They’re wearing their swimsuits and hanging out at the beach with their friends. That’s the standard of care that we have today.”

Finding ways to improve patient outcomes through research

When a piece of the skull is missing, the brain collapses against itself because there’s no structure to cradle it in place.

“We reconstruct it. You don’t make it contour to the brain. You make it round and then the brain expands to fill whatever you put there,” Dr. Mitchell says.

For reasons that are still unclear, there are sometimes wonderful, unexpected improvements in brain function after skull reconstruction.

Patients may be able to re-use their limbs. In some cases, speech returns.

It’s not something Dr. Mitchell can promise patients, though.

“We need more research. Right now, we don’t have the data to be able to say that,” she says.

Dr. Mitchell is creating a patient registry that will track outcomes years after surgeries.

Her lab collaborates with others at Ohio State to study how cranioplasty techniques can be improved, focusing on re-using the patient’s own bone, lowering infection rates and helping patients heal faster.

In many cases, the skull pieces can be frozen and saved after they are removed while a patient heals from initial surgery. Her research explores ways to re-vascularize the bone or build out scaffolding to better support the bone.

'Perfect to me’

Vicki, from Wooster, in northeast Ohio, is thankful for the neuroplastic surgery program.

“It makes me so happy. I can’t even explain it,” she says.

Vicki’s life was initially saved thanks to Ohio State’s telestroke program, connecting rural patients to emergency stroke care.

Vicki underwent three surgeries related to her stroke, beginning with emergency stroke surgery with Dr. Youssef.

When her skull bone was initially replaced after her stroke surgery, Vicki developed an infection. It meant her natural skull bone had to be discarded.

“It’s a very emotional thing, but after I had the first surgery, I felt like I lost everything, all the gains that I had made,” Vicki says. “I later learned that was normal.”

She couldn’t walk without assistance. Her short-term memory was strongly affected.

“I didn’t feel like I was me at all,” Vicki says.

But after her cranioplasty with Dr. Mitchell, she started improving.

"The first thing I did was just run my hand through and see if I could feel between my skull and the implant. Is there a dip or anything?” Vicki says.

“It looks and feels perfect to me.”

About six weeks after her last surgery, Vicki continues to make gains.