Solving the mystery of sudden cardiac arrest in the young and healthy

When a young mother and former Division 1 athlete has a sudden cardiac arrest at age 27, Ohio State’s heart team investigates the underlying cause.

Shayna (Harmon) Hemming was an outstanding athlete in high school, lettering in basketball and softball. A 2016 graduate of Teays Valley High School, south of Columbus, Ohio, Hemming holds the record for the most points scored in basketball for any player in Pickaway County. She attended the University of Akron on a Division 1 basketball scholarship, and by November 2024, Hemming was busy living her dream. After graduating from college, she returned to her hometown and married her high school sweetheart. Two healthy children followed.

And then, an unexpected sudden sudden cardiac arrest at age 27 changed everything Hemming thought she knew about her own body.

The day before her emergency, she remembers, they were enjoying Thanksgiving dinner at her parents’ house just two streets away from where she and her husband live. She remembers taking her son back to the house later that night for more pie. But after that, she only knows what her family has told her about the next morning and the critical days that followed.

Around 4 a.m., her 2-year-old son Greyson came to his parent’s bedroom. Shayna told him to lay down, and minutes later, Trevor Hemming heard Shayna struggling to breathe. Unable to wake her, he felt for a pulse but couldn’t find one.

“Greyson and Trevor are my heroes,” Hemming says.

While Trevor kept Shayna alive with CPR, he called 911 and contacted Shayna’s parents. They rushed to the house and cared for Greyson and 5-month-old daughter Callen while paramedics arrived. Hemming’s father posted a message to friends and family on Facebook: “Please pray for our family.”

Later, people would tell Hemming they prayed not knowing who was ill. “They said, ‘Well it can’t be Shayna. She’s the healthy one,’” she recalls. “It was a shock to everyone.”

After Hemming was stabilized by paramedics, she was rushed to a nearby hospital and then transferred to The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center Richard M. Ross Heart Hospital.

There, cardiologists and other specialists assembled to seek one answer: Why does a young, healthy person like Hemming have a cardiac arrest?

Solving a sudden cardiac arrest mystery

Hemming’s initial tests showed arrhythmia, or an irregular and rapid heart rate, coming from the bottom chamber of her heart, which resulted in her sudden cardiac arrest. At the Ohio State Richard M. Ross Heart Hospital, she was fitted with a device called an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD). Similar to a pacemaker in appearance, an ICD differs in that it detects an abnormal heart rhythm, which can be life-threatening, and provides the necessary therapy by shocking the heart back into normal rhythm.

“We put in hundreds of these devices every year,” says Salvatore Savona, MD, a cardiologist at the Ohio State Ross Heart Hospital who specializes in electrophysiology, the heart’s electrical system. He diagnoses and treats abnormal heart rhythms.

“Her case really highlights how we should approach situations like hers,” he says.

In an arrhythmia case like Hemming’s, tests can determine whether there are structural issues in the heart muscle that cause the abnormal heart rate or whether there are electrical issues that need to be fixed.

“Is it the pump, or the wiring?” Dr. Savona asks. “She had a young baby, and [her cardiac arrest] was a dramatic experience for everyone involved.”

While an ICD is a common solution, the issue with Hemming’s heart muscle is quite rare.

Uncovering the source of sudden cardiac arrest in a young person

Hemming left the hospital with her new device, but without understanding what had caused her sudden cardiac arrest. Dr. Savona and the cardiac genetics team approached her case like detectives. While initial tests had indicated an electrical problem, further testing, including an MRI, revealed a problem with the right side of her heart: cardiomyopathy of the right ventricle.

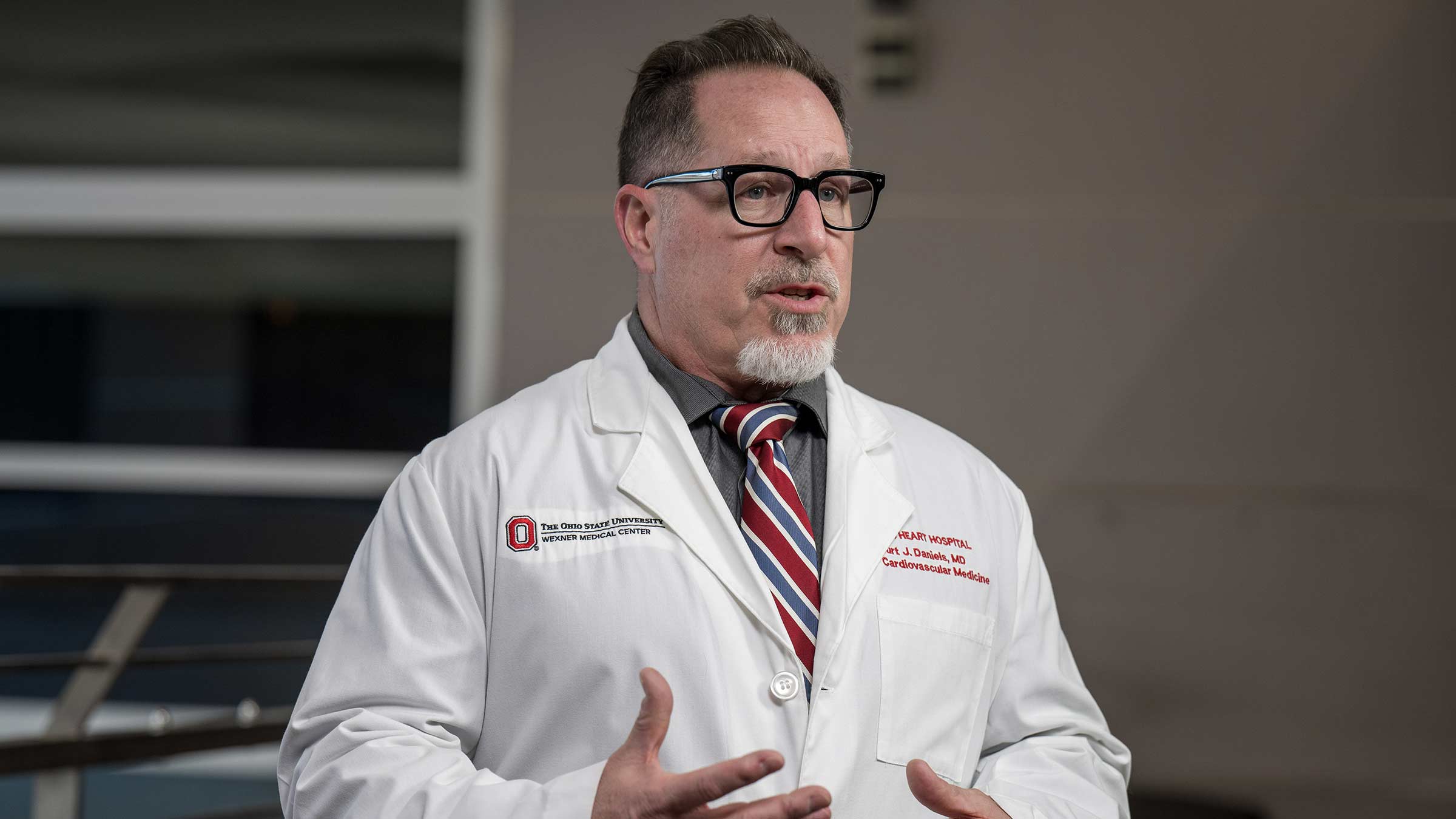

Curt Daniels, MD, medical director for the Ross Heart Hospital and director of the Adult Congenital Heart Disease (ACHD) Program, was on call the day Hemming arrived. Caring for young adults with heart disease is one of his specialties.

“Structural problems are not necessarily genetic,” Dr. Daniels says. But in Hemming’s case, the structural abnormality is caused by a rare gene mutation. This genetic disease is characterized by changes to the heart muscle, including a buildup of scar tissue that leads to disruptions in the electrical signals, causing arrhythmia.

Elizabeth Jordan, GC, a genetics counselor with the Ross Heart Hospital, also was consulted when Hemming first arrived at Ohio State.

“Because Shayna had arrhythmia and cardiomyopathy features, we looked at genes important for both heart rhythm and muscle. From there, we found the mutation that causes problems with the right ventricle,” Jordan says.

From that mutation, Hemming was diagnosed with desmoglein cardiomyopathy caused by an abnormality in the sequence of one of her two copies of the DSG2 gene. Although the abnormality was unknown to Hemming, she’s had it her whole life.

“This disease often presents itself in patients who are in their 20s, but could present later in life as well,” says Dr. Daniels, who holds the Dottie Dohan Shepard Professorship in Cardiovascular Medicine. “The genetic testing helped us to identify her gene, but the advanced cardiac imaging and the cardiac arrest helped guide genetic testing. We are fortunate to have world-renowned, advanced cardiac imagers and electrophysiologists who specialize in genetics on our team.”

“She’d already been through the hard part,” Jordan says, referring to Hemming’s sudden cardiac arrest. “Shayna’s first question was about her children.”

Heart genetic testing provides valuable information

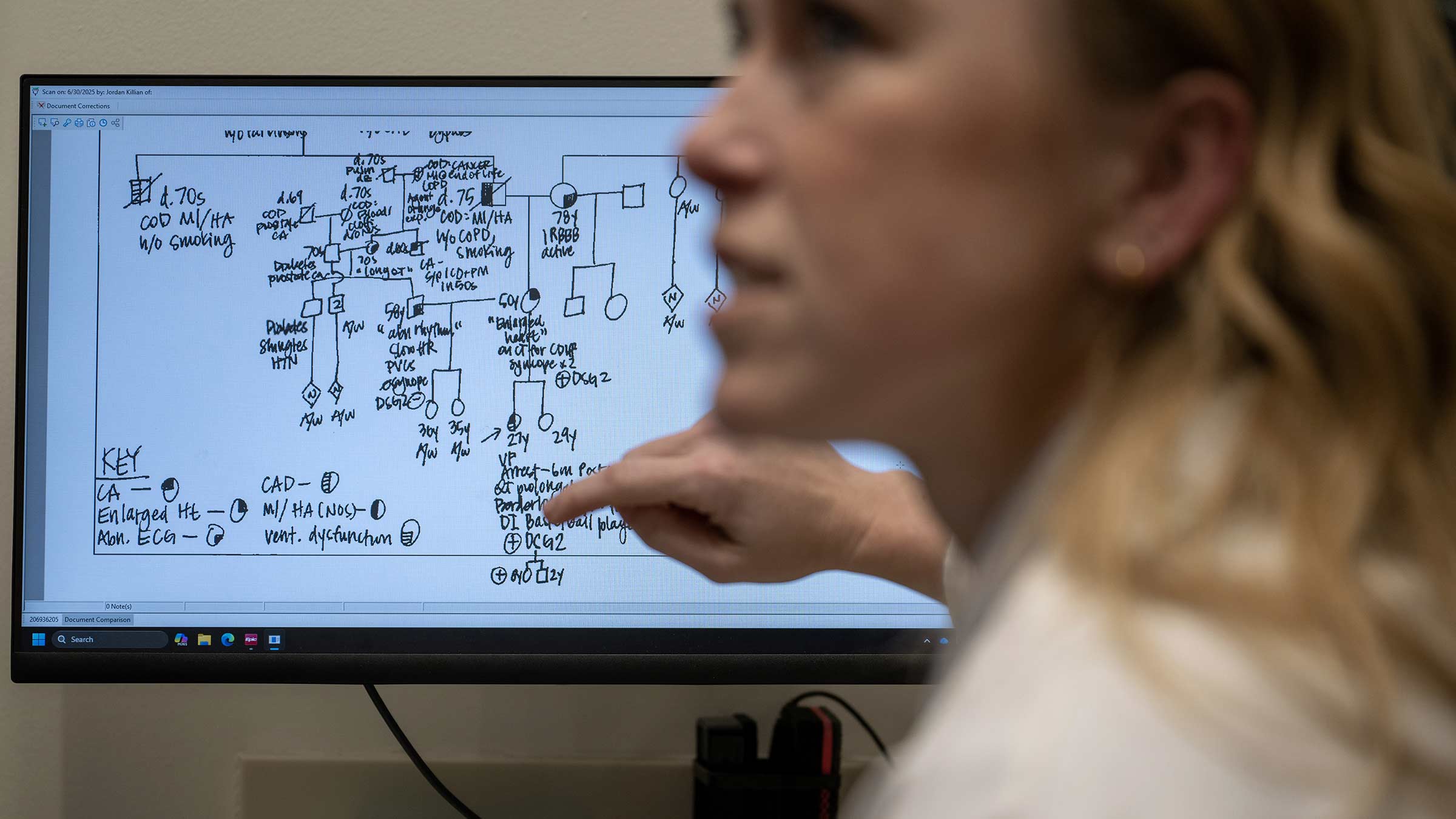

After Hemming’s diagnosis, Jordan began working with the entire family to determine if anyone else had the abnormal gene.

“They were all-in,” Hemming says of her siblings. “They all have kids too, so we wanted to figure this out.”

The genetics team collected family health histories from Shayna, her parents and grandparents, and her sister, along with their children.

“My dad told me that he hoped [the abnormal gene] was from his side of the family because he knew how upset my mom would be to think she gave this to me,” Hemming says.

Her mother, who had no symptoms of heart problems, tested positive for the gene, but her grandmother didn’t. Hemming’s maternal grandfather, who has passed away and can’t be tested, may have had the mutation. Or it may be new, starting with Hemming’s mother. Shayna’s daughter, Callen, also tested positive for the mutation. Shayna’s sister doesn’t have it.

While some people are reluctant to get tested, Jordan believes in being prepared by understanding potential risks. Sharing information is important, and dealing with risks can cause lots of complicated feelings.

“It’s important to control what you can control and use genetic risk information to be proactive, not reactive,” Jordan says. “And it’s a cause for her sister’s celebration, to know that she doesn’t have the abnormal gene and neither do her sister’s children.”

“Now that we have a diagnosis, Shayna has answers and can be directed to the appropriate teams to help her manage her condition,” Dr. Savona says. In addition, pediatric cardiologists at Nationwide Children’s Hospital are following Hemming’s daughter. Dr. Daniels also works with that group of specialists.

The lifesaving value of CPR

Dr. Daniels is a proponent of learning and using CPR and AEDs (automated external defibrillators).

“The only way to save lives [outside of the hospital] is CPR,” Dr. Daniels says.

“CPR provides circulation to the heart and brain and should be performed until an AED is available to shock the heart back into rhythm and provide the best chance for survival.”

“That’s the greatest part of Shayna’s story,” Dr. Daniels says. “So many things had to happen. She is neurologically OK, and fully functioning, which is amazing. He gave her CPR and saved her life.”

Hemming is gaining strength every day, working with rehabilitation specialists who monitor her heart while she walks on a treadmill.

“I’m getting better, rather than being worried,” Hemming says. “I’m living every day.”

She believes surviving sudden cardiac arrest was a gift to her, so they can help her daughter avoid a sudden cardiac incident in the future.

“We don’t need to be scared,” Hemming says. “We need to be prepared.”

Your heart is in the right place

Learn more about advances in care and treatment for patients at The Ohio State University Heart and Vascular Center.

Expert care starts here