Surgery brings seizure freedom for drug-resistant epilepsy

How one young man regained independence after minimally invasive surgery.

Of the many epileptic seizures Noah Braholli had at work, he can describe one, which was caught on a security camera, in great detail. Braholli is standing in a yellow hat behind the counter. Suddenly, his body jerks to the left, and he stumbles out from behind the counter. He crosses the room and slams into a wall-mounted television monitor. Like a spinning top, he bounces back toward the counter, where he faceplants into the computer monitor there, knocking it to the floor.

He finally collapses on the floor as his coworkers rush to help him. The whole clip lasts mere seconds. “Thankfully, everything was fine, myself and electronics included,” Braholli says.

Knowing he could have an epileptic seizure at any given moment meant his condition affected every part of Braholli’s life. He was fortunate to have family and a partner who supported him, as well as coworkers willing to learn what to do in case of a seizure.

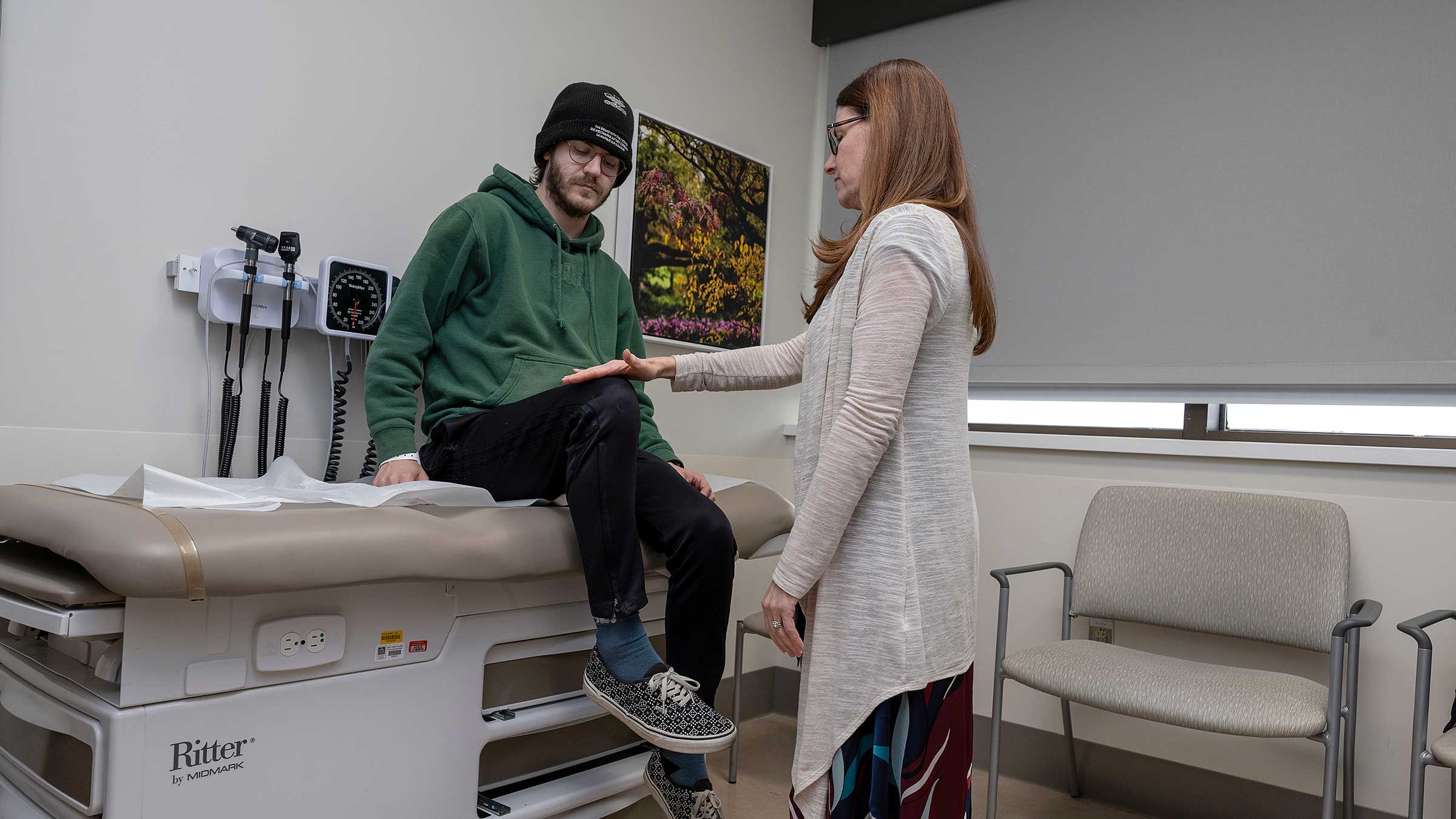

Still, epilepsy kept Braholli, 26, from driving, going out in public alone and traveling anywhere unfamiliar. His world shrank as his seizures increased. “I used to be a very independent person. I just wanted to get my life back to normal,” Braholli says.

Today, after becoming a patient of Ohio State’s Comprehensive Epilepsy Center and undergoing a brain surgery one year ago, Braholli is seizure-free.

Getting an epilepsy diagnosis

The first time he had a seizure in 2021, Braholli was in bed, sleeping next to his partner. The next thing he knew, he was waking up in an ambulance with no memory of what had happened. “Nothing like that had ever happened before, and I couldn’t lift my arms because they hurt so badly. That was probably the most intense seizure I had,” Braholli says.

Having one unprovoked seizure didn’t necessarily mean Braholli had epilepsy. He left the hospital with hopes the seizure was an anomaly. There’s no single test to diagnose epilepsy, and many people who have one seizure never have another.

Within a month, Braholli had another seizure and was referred to a neurologist in his hometown of Canton, Ohio. Braholli was diagnosed with epilepsy and began taking medication to control his seizures.

Understanding drug-resistant epilepsy

One in 26 people will have epilepsy at some point in their life. Medication is effective for about seven out of 10 of them. That leaves 30% of people with drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE) — including Braholli.

The International League Against Epilepsy defines DRE as occurring when a patient has failed two or more medications at adequate doses. At that point, studies show the likelihood of becoming seizure-free with a third or fourth drug is less than 5%.

Epilepsy is a progressive disease where seizures tend to become more frequent, severe and increasingly damaging to the brain. “Seizures affect memory and emotions, so the longer you have uncontrolled seizures, the more you could develop irreversible symptoms,” says Jaysingh Singh, MD, a surgical epileptologist (a neurologist who specializes in epilepsy) who performed Braholli’s surgery.

Besides damaging memory, seizures can cause depression and anxiety, limit education and employment opportunities and affect social relationships.

“You want to move as quickly as you can in this journey, because the longer you wait, the harder it is to get them seizure-free,” says Danielle Becker, MD.

Before surgery, the longest Braholli went without a seizure was four months. There were times he had multiple seizures a week. “After about two years of medication, he threw his hands up and said we need to get some bigger brains in on this because what we’re doing isn’t working,” says Ripley Villers, Braholli’s partner, who’s supported him throughout this challenge.

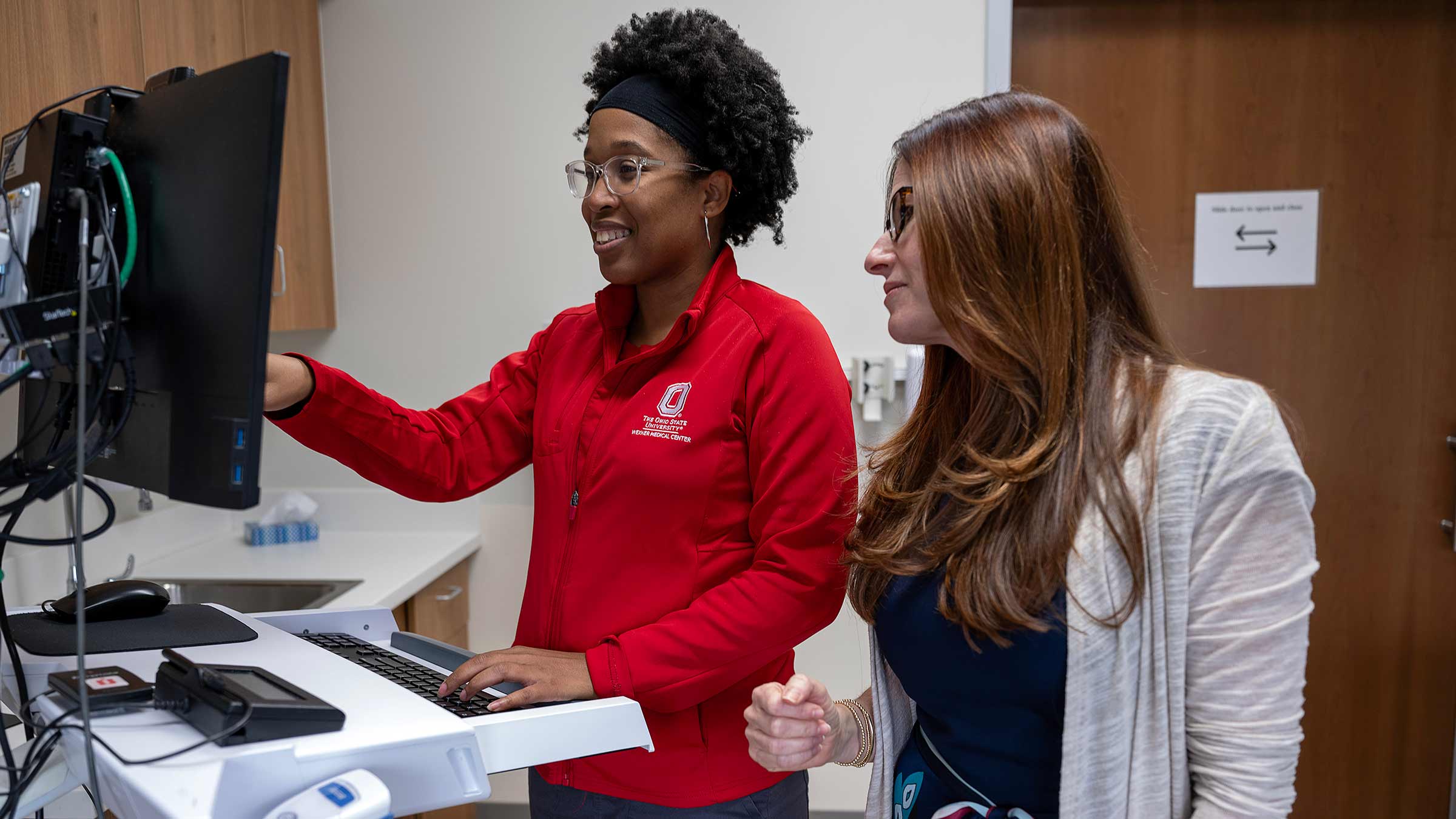

Braholli’s local doctor referred him to Dr. Becker at the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, a level 4 comprehensive epilepsy center.

Finding the seizures’ source

Braholli underwent a series of tests to determine his baseline functioning. Each test is a piece of the puzzle to identify where the seizures occur in the brain. Dr. Becker presented the information to a team of epileptologists, neurosurgeons, radiologists, neuropsychologists and other epilepsy providers.

“We work together to recommend what’s most likely to make someone seizure-free without worsening their memory or cognition,” Dr. Becker says.

For Braholli, the team recommended a minimally invasive laser ablation surgery, using an MRI-guided laser to remove the source of the seizures, while sparing the area around it.

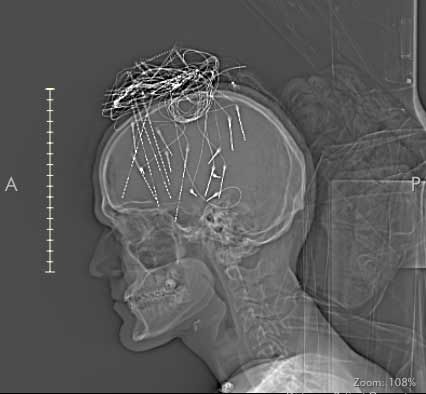

The team knew generally from the neuro testing where in Braholli’s brain seizures occurred, but they needed to determine the exact epileptic focus. To do this, the team used robotic arms in an imaging procedure called stereotactic encephalography (SEG) to implant tiny electrodes the size of coffee grains into Braholli’s brain.

From there, the epilepsy monitoring unit team observed Braholli’s seizures to help diagnose their source. Because he sometimes had violent seizures and would lash out at those trying to help, safety was a top priority.

“We needed seven people to keep everyone safe, while also maintaining the goals of monitoring the seizures, and that’s where our team stood out as very brave and met both the goals,” Dr. Singh says.

Once his doctors reviewed monitoring results, Braholli underwent his first of two surgeries to remove the focus of the seizures in his temporal lobe on the right side of his brain. The surgical team inserted a probe into a small, single incision at the back of Braholli’s brain to destroy the area around the electrode with thermal heat.

“The fact that they were going to be operating on my brain was something that was kind of scary, but I was blown away by how fast it was,” says Braholli, who stayed in the hospital for only one night and had a quick recovery.

Finding freedom from epileptic seizures

Braholli’s seizures improved after the first surgery, but he wasn’t seizure-free. Three months later, he underwent a second laser ablation.

After that, Braholli had one more scary seizure while walking on the side of a road. He called Dr. Becker, who recommended a slight increase in his medication. That, combined with both surgeries, finally gave him seizure freedom.

Today, it’s been a year since Braholli’s last seizure — the longest period since his diagnosis. “The longer someone goes without seizures, the more likely they’ll continue to be seizure-free, so a year is a pretty big celebration for him,” Dr. Becker says.

Options beyond epilepsy surgery

Sixty percent of epilepsy surgeries at Ohio State help people become seizure-free. However, surgery isn’t always an option for those with DRE. Sometimes, seizures come from both sides of the brain. Other times, the seizure focus is located around brain regions like speech, motor, vision or memory, making surgery a challenge.

In these cases, neuromodulation, like a “pacemaker for the brain,” can help. Seizure freedom is more likely with surgery, but there’s an encouraging 50 to 75% reduction in seizures across the three neuromodulation devices available at Ohio State.

Seizure rescue medication, like what Braholli brought to work and explained to coworkers, can also make a significant difference for those with epilepsy. “Epilepsy is a scary disease, but even if we can’t stop someone’s seizures, we can try to reduce their frequency and severity and improve their recovery time and ultimately their quality of life,” Dr. Becker says.

Researching the future of epilepsy treatment

Braholli’s procedure only required a single incision, but future epilepsy surgeries might not require any. Researchers at Ohio State are involved in a clinical trial to study the effectiveness of high- or low-frequency ultrasound to remove tissue at the source of seizures. “That’s the future. Just imagine epilepsy surgery in a tiny spot without ever touching your scalp,” Dr. Singh says.

Researchers are also studying new epilepsy drug trials, as well as gene therapy studies to repair the dysfunctional tissue.

To help more people with epilepsy access treatment, Dr. Becker and her team spend a lot of time educating the public and colleagues about the options available. While about 1.2 million people in the United States have DRE, too few are treated with surgery or neuromodulation. “There’s a massive treatment gap, and those of us providing care in the epilepsy community want to know why. Everyone should be offered something,” Dr. Becker says.

Enjoying everyday life

Today, Braholli continues to take daily medication to prevent seizures, and he makes sure his coworkers know where to find his seizure rescue medication kit. Still, the longer he’s seizure-free, the more his epilepsy becomes an afterthought.

“Every morning, we had to determine if today was going to be a seizure day or not. Just being able to go back to everyday life and not have his epilepsy be the first thing we have to think about is the biggest way the surgery changed our lives,” Villers says.

Take charge of your nervous system

Learn more about the causes of neurological conditions and treatment options available at Ohio State.

Take charge today