Transforming lives, one organ transplant at a time

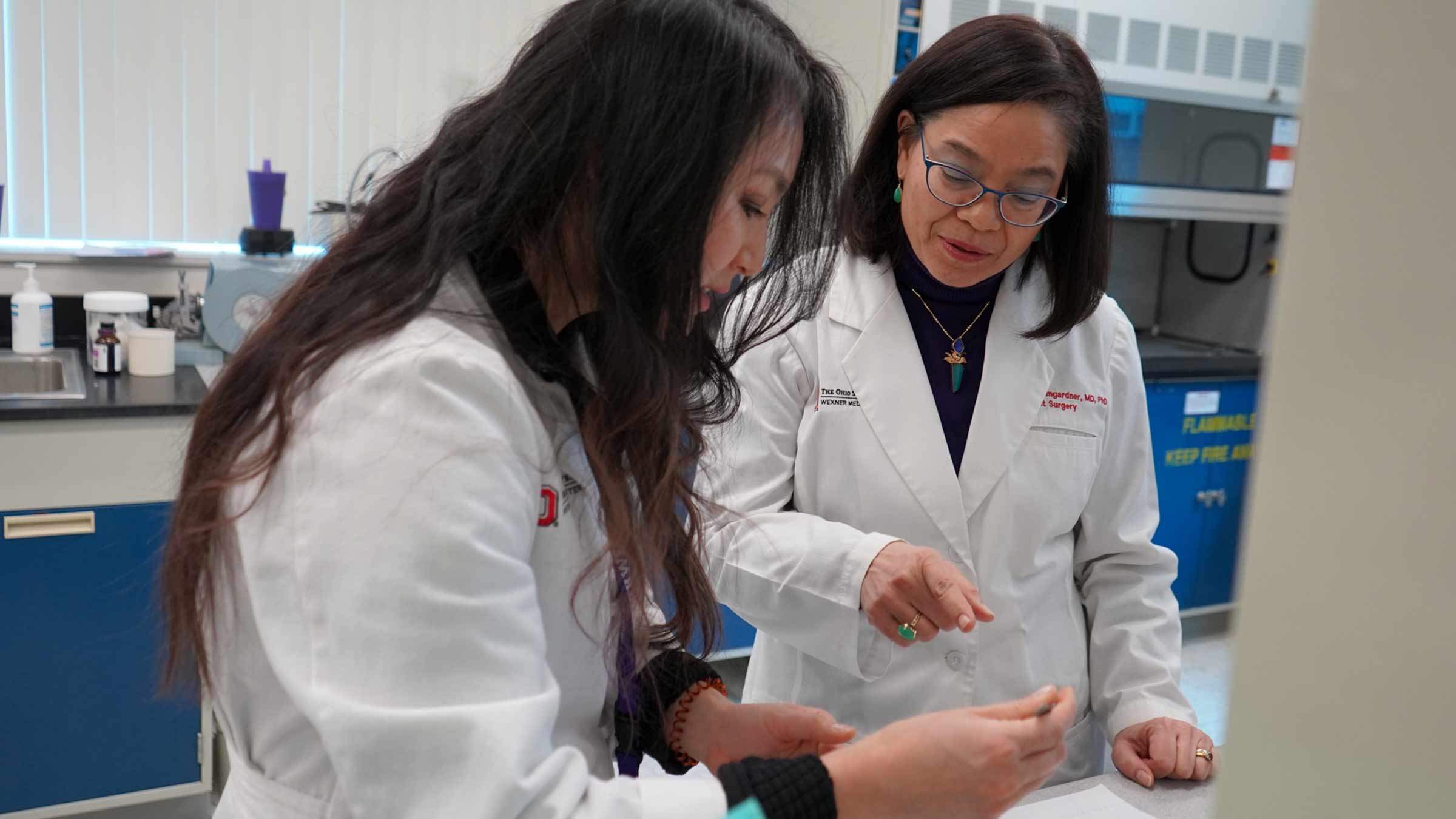

From surgery to research to mentoring, Ginny Bumgardner, MD, PhD, is saving lives and empowering others to do the same.

James Green has been here before, in this same room, the one with the view of downtown Columbus high-rises and a parking garage.

He knows Room 1030, having stayed in it a few times in the past nine months. He’s received two organ transplants: his liver last fall, his kidney in June.

Days after his kidney transplant, Ginny Bumgardner, MD, PhD, sketches a diagram on the dry-erase board by his hospital bed, showing Green how his donor kidney was transplanted. She explains why he needs to keep drinking not just water, but Gatorade and juice for electrolytes.

He feels great, he tells Dr. Bumgardner, who performed the transplant surgery.

Already, Green is thinking about golf and his friends who are texting him from the greens.

“I had a tee time today at 10. I don’t think I’m going to make it,” he jokes.

Green’s wife, Lori, can’t believe how much better his health is than it was a year ago.

“He’s very lucky,” she says.

Supporting patients and the next generation of transplant surgeons

In the three decades Dr. Bumgardner has been a surgeon, she’s transplanted a few thousand organs, mostly kidneys, livers and pancreases. All the while, she’s passed along her skills in surgery and research to countless young physicians, inspiring many to follow her career path, which was not typical.

Early in her career, Dr. Bumgardner made a decision uncommon at the time for physicians — especially women. While she trained to become a surgeon, she pursued a doctoral degree to become a physician and scientist. She chose immunology, the study of the immune system, which plays a key role in how long a donor organ, once transplanted, will function.

“As a medical student, I was fascinated by how complex the immune system is, how it protects us from infections, heals injuries and fights cancer,” Dr. Bumgardner says.

“I knew immunology would be important no matter what specialty I chose.”

That degree in immunology allowed her to not only transplant organs and care for the patients who received them, but also research ways to solve one of the most complex challenges with transplanted organs: keeping them working long-term.

The gift of life – given twice

When James Green woke up on Sept. 13, 2024, his face was completely yellow. After several days of tests in a hospital near Green’s home in Uniontown, Ohio, staff told Lori Green her husband’s health was fragile.

“They said he wouldn’t live more than two months unless he received a liver transplant,” she says.

Within a week of being put on a list for a donated liver, Green was offered one from someone who had just died.

The turnaround time was even faster, closer to two days, in June 2025, when Green needed a kidney donor. Since his liver transplant at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, medical staff had kept close watch on his kidneys with regular blood tests.

“We knew the kidney was going to be an issue,” Green says. “We just didn’t think it was going to be that quick.”

Just a couple of days after his name was put on a list for a donor kidney, he and his wife got a phone call around 2 a.m.

“We thought: ‘This can’t be about a kidney donor,’” Lori Green says.

Her husband’s kidney was replaced later that day.

Extending the life of a transplanted organ

When someone receives a donor organ, their immune system will treat it like an intruder, making antibodies, proteins that can attack the new organ.

It’s not common for the immune response to cause a transplanted organ to fail within the first year. However, when Dr. Bumgardner began working as a transplant surgeon a few decades ago, the odds of rejection within the first year were as high as 40%. The current odds are 10% or less.

Various medications available now can keep the body’s defenses from harming a transplanted organ, so it works well longer.

But after several years, medications can’t always stop the immune system from damaging the transplanted organ.

“There are many patients who do well for years. But over time, their organs stop working because antibodies they produce damage the organ,” Dr. Bumgardner says.

Dr. Bumgardner and her research team discovered a type of immune cell the body makes that can reduce or prevent the creation of antibodies targeting the transplanted organ.

This immune cell is in the family called CD8+ T cells. The number of these cells in a person can help predict how likely they are to produce antibodies that harm the transplanted organ. Dr. Bumgardner’s team is now working to understand how these cells develop and how to reproduce them to create therapies that will lengthen the life of transplanted organs.

“If scientists can grow these immune cells in a lab, they can be given to certain patients to prevent their immune system from creating antibodies that attack the organ,” Dr. Bumgardner says. “The cells could also be used to treat someone if their immune system has already begun making antibodies against the transplanted organ.”

Mentoring the next generation of physician-scientists

Part of caring for patients is making sure they have the best possible treatments, which is why Dr. Bumgardner pursued a career in immunology research. She’s mentored countless medical students and resident physicians, steering many into research careers.

A little over a decade after she began working at the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, Dr. Bumgardner developed the first structured research training program for surgeons at The Ohio State University College of Medicine.

She would go on to increase access to the master’s degree program in medical science for resident doctors and fellows.

“She transformed the way we encouraged and supported medical student research at Ohio State,” says Daniel Clinchot, MD, a Professor Emeritus of Biomedical Education and Anatomy at the College of Medicine.

“She’s always willing to work with students to find a mentor or projects that will keep them involved in research.”

Jenny Barker, MD, PhD, was a resident physician at Ohio State in 2014 when she met Dr. Bumgardner, who became her longtime mentor.

“I’ve found it very inspiring to try to follow in her footsteps because of her infectious enthusiasm,” says Dr. Barker, now a plastic and reconstructive surgeon at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, where she also runs a laboratory with the Center for Regenerative Medicine.

“Dr. Bumgardner is a passionate advocate for physician-scientist careers. Her impact is far-reaching. It’s a bit of a waterfall scenario. She impacts dozens, and each of them has the opportunity to influence others. It’s truly exponential.”

Back on the golf course

Living with two donated organs, Green can’t help but think about the two people who, in death, gave him many more years to live. He wonders: Were they sick? Did they get into an accident?

Someday, Green says, he might want to reach out to their surviving relatives and say how much he appreciates the gift he never expected to need.

He also never expected the wait for a donor organ would be so brief — not once, but twice.

“It amazes me how well everything went,” he says.

Recently retired from his job selling construction materials, Green plans to return to golfing. Before the kidney surgery, he golfed all but two days a week. Slowly, he’s going to get back into it, first just riding in the golf cart with friends, then picking up a club and swinging again.